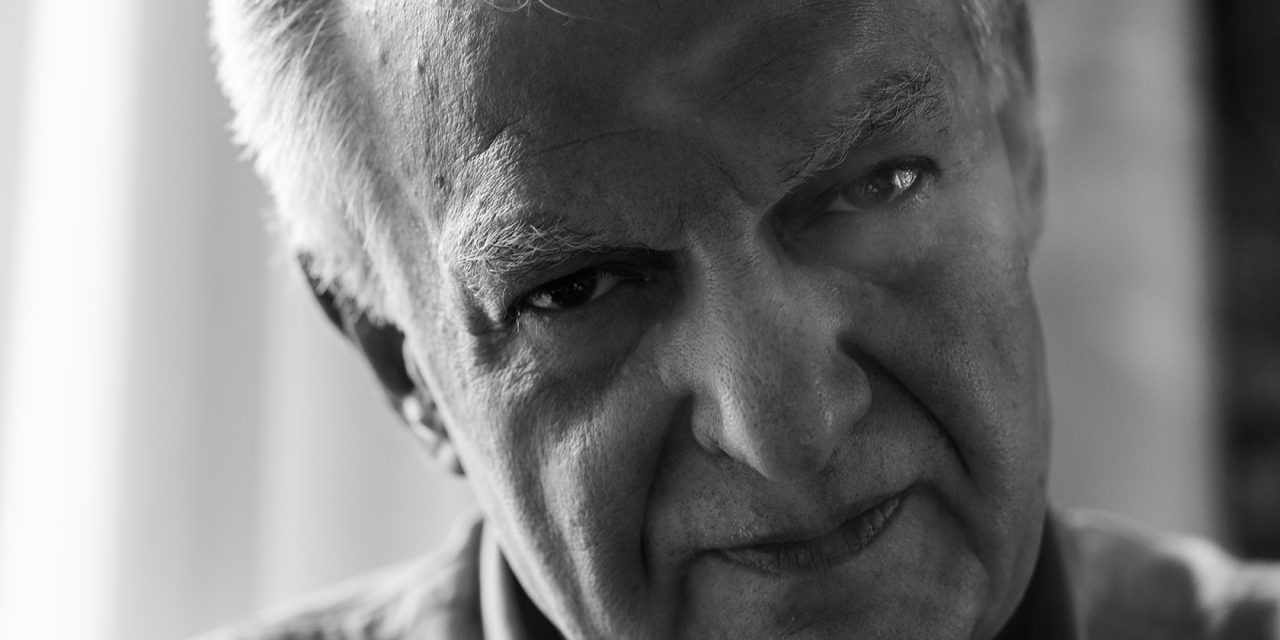

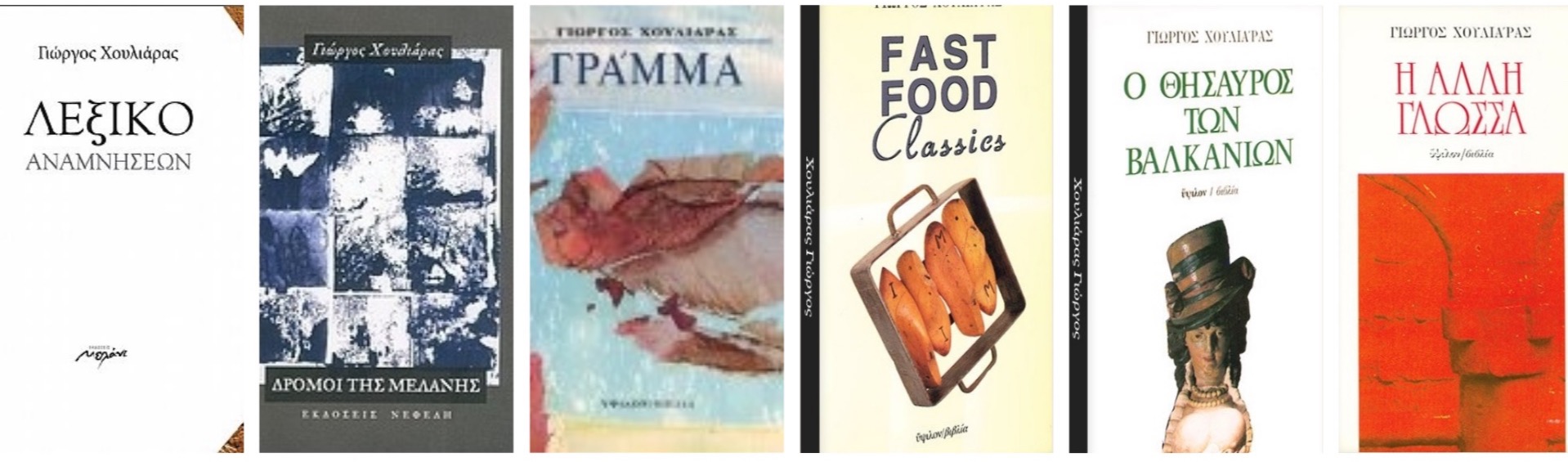

Yiorgos Chouliaras is a Greek poet, prose writer, essayist, and translator. Born in Thessaloniki, he studied and worked mostly in New York, before returning to Athens from Dublin. He has worked as a university lecturer, advisor to cultural institutions, correspondent, and Press Counselor at Greek Embassies in Ottawa, Washington, DC, and Dublin. His books include: Iconoclasm (Thessaloniki: Tram, 1972), The Other Tongue (Athens: Ypsilon, 1981), The Treasure of the Balkans (Athens: Ypsilon, 1988), Fast Food Classics (Athens: Ypsilon, 1992), Letter (Athens: Ypsilon, 1995), Roads of Ink (Athens: Nefeli, 2005), and Dictionary of Memories (Athens: Melani, 2013).

He was a co-founder of the influential Greek literary reviews Tram and Hartis and an editor of literary and scholarly publications in the United States, including the New York-based Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora and the Journal of Modern Hellenism. He has been an advisor to cultural institutions, including MOMA, the Cultural Capital of Europe, and the Hellenic Foundation for Culture, and has helped organize hundreds of literary & scholarly meetings, exhibitions, concerts, and other cultural events in major museums and academic institutions in North America and Europe.

In 2014, he was awarded the Ouranis Prize of the Academy of Athens for his alphabetical anti-memoir Dictionary of Memories and his work in its entirety. His poetry in translation has been published in major periodicals and anthologies, including Harvard Review, The Iowa Review, Ploughshares, Poetry, World Literature Today, and Modern European Poets, and in Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Italy, Japan, and Turkey among other countries. He has been elected President of the Hellenic Authors’ Society and to the Board of other literary and scholarly associations.

Yiorgos Chouliaras spoke to Reading Greece* about what changed and what remained the same since his first book Iconoclasm in 1972, noting that “writing is a conspiracy of immortality, a failing effort to cheat death by slipping messages to the future”, and that “no language can sustain itself without literature and there is no life without language”. He also comments on the so-called generation of the 1970s, explaining that “it was a generation of poets who grew up writing in times of constraints and frustrated expectations” and that “initial abstention from publication was coupled with renewed commitment to writing”.

As for the role of the Hellenic Authors’ Society, he notes that it “remains engaged, collectively and individually through its members, in events of major cultural significance and Greek interest whether inside or outside the country, and as a representative of Greek authors in European and international initiatives”. He concludes that “the complex – rewarding as well as frustrating, utopian as well as dystopic – relation Greeks have to their past remains of paradigmatic interest to those struggling to make sense of their lives” and that “as a country of the imagination and a widely recognized point of origin, Greece is a place where you can discover yourself and the world”.

From Iconoclasm in 1972 to Roads of Ink in 2005 and Dictionary of Memories in 2013: What has changed and what has remained the same in these forty years? How are notions of love, memory, and death dealt with in your writing?

Nothing has changed, though everything has. Continuity is established through discontinuities. This is the case for individuals and their history as well as history at large. Moreover, there are two types of memory: What others remember about us and what we forget about ourselves. The fact that death is possible at any age is a simulation of immortality as you grow older and this event becomes more probable. With symbiosis equally impossible and necessary, love remains a guiding principle, as long as love of others and love of things, also called curiosity, somehow modulate love of one self. Keep trying, keep failing, fail better, Beckett suggested. Do not approve. Do not disapprove. Prove. Search for the kind of humor Kafka demonstrated. Avoid insincere seriousness in any serial of yourself. Be self-sarcastic. The tragedy of human life is that it is a comedy. Do not imitate yourself. Keep fighting with and against those icons, images, words that could be your friends. Someone else may be better suited to write your autobiography. Are you post-modern? I was asked in an interview in the U.S. No, I’m post-ancient, I said.

“I write so as not to forget/ I don’t write to forget/ Don’t forget that I write.” What drove you to writing, and poetry in particular, and what continues to be your driving force?

Writing is a result of reading, which is a result of writing. Both skills are learned and, in that sense, unnatural, though, as with all skills once learned, it becomes impossibly difficult to imagine what it was like before you came into them – in part accidentally and by imitating elders in the tribe, but also through schooling, in schools or outside them. No one is born a writer, as one person’s life is too short to invent writing, even though we seem to re-invent the wheel every day. Writing is a conspiracy of immortality, a failing effort to cheat death by slipping messages to the future. Written words set up islands in the vast archipelago of the spoken word. This is why poetry must always pretend to return to its oral origins. Listen to the music of what is being transcribed. Even if people imagine that writing is a hidden way to reveal yourself, it remains the most revealing way to hide oneself. Poetry, as a womb of all writing, issues the stuff angels and demons are made of. This involves words and numbers, love for which is a precondition of creation, even when it must be tough love. Writers continue to write to the extent no one, including them, grasped that first poem they wrote. No one stood under it. The immateriality of speech is the kind of material we make.

“Literature is not, as it should be, just consolation and recreation or entertainment of the soul. Literature, as a utopia, is also criticism of a real topos.” What was the contribution of poetry and literature in general to the formation of the Greek nation? What role is literature called to play nowadays?

Greece was generated by poetry. Despite any hyperbole, this is historically grounded on distinct ancient and modern instances. Carried along by Aristotle’s student Alexander, Homer’s epics created and selected bonds among Greeks from Ithaca to Asia Minor and from islands in the south to Macedonia. This is how nations were formed before nationalism. Much later, by assuming the exemplary role of a bard from whose verses the national anthem was derived, Solomos imagined a reincarnation of Greece as a modern state. At the same time, Byron expended his life for the place that made him a poet, he claimed, while his comrade Shelley, who never visited the country, proclaimed that “we are all Greeks.” Poetry became what I have described as “a regulating discipline,” with Cavafy and two Nobel laureates broadly defining Greece’s share on the modern map of world culture. Comparisons for offspring of renowned parents only lead to disappointment, however, while poetry is generally regarded as in retreat in destitute times, in Hölderlin’s formulation. A strategy of measured expectations is called for. Regardless of the quality of what may be produced now, it could never compare favorably with the distilled best of what came before. Literature is no exception. All the same, no language can sustain itself without literature and there is no life without language.

It has been said that you belong to the so-called generation of the 1970s. What makes this generation different from what preceded and what followed it?

This was a generation of poets who grew up writing in times of constraints and frustrated expectations. The military dictatorship repressed promises of political normalization and social perforation coming up after the civil war, the only extended one in a European country after Nazi defeat. A process of postwar “cultural reconstruction,” as I have called it, was blocked, even if it was very difficult to have access to outside trends already before the junta years. Initial abstention from publication was coupled with renewed commitment to writing. There was a range, from direct protest to the development of allusive writing that could escape the censors’ radar. Surrealist poems appeared as allegorical as folk songs. It was a Western version of an East European experience that further confused the compass regarding East and West or North and South. Younger writers started to become visible, surfing on the same wave, though quite differently among themselves. This is why I was critical of such a notion of a “generation” that corresponded only to publication synchronicity and became an excuse to ignore previous writers. Once the wave passed, however, it no longer appeared fair to criticize underdogs, even if I personally prefer cats, as they seem more independent.

During the 1970s and 1980s, you co-founded and edited major literary magazines, such as Tram and Hartis. How would you comment on current literary and artistic projects in the era of online communication?

Indispensable as they are, books are better suited as an end rather than a beginning of a process that includes periodical publications, both print and electronic now. Periodicals reflect the vitality of a cultural moment. Incomplete as all revolutions, the electronic revolution is the kind of blessing and curse that literature & the arts cannot stay away from. It’s still early though, with few projects exploring the possibilities of this medium or message that has not been decoded. It still is as if people were filming theatrical performances thinking they were making movies. Yet, involvement must be encouraged. I know there is fragmentation. I know there is trash. But I refuse to assume the position of older people criticizing younger people for the kind of music they listen to. They have the right to be wrong.

What is the role that the Hellenic Authors’ Society is called to play especially at times of crisis? What about the prospects of Greek literature and the new generation of Greek writers in this respect?

The Hellenic Authors’ Society was established after the collapse of the dictatorship, with Odysseas Elytis as its first honorary president, to bring poets, prose writers, essayists, translators, and literary critics together in defense of freedom of expression and in support of their creative and professional interests. These objectives are always current, while the Society, as the principal association of Greek writers, remains engaged, collectively and individually through its members, in events of major cultural significance and Greek interest, whether inside or outside the country, and as a representative of Greek authors in European and international initiatives. At the same time and with very limited resources in crisis conditions, the Society must address existential questions in the very mundane sense that health insurance, pensions or taxes affect the very existence of writers in pernicious circumstances. This is not a simple set of issues to be dealt with by an elected Executive Board of unpaid volunteers who must also balance conflicting demands of encouraging the election of younger writers as new members, but in accordance with a peer review process required for their election. It must be added that, although writers may continue to write under trying circumstances, the contemporary impact of their presence in a national setting and internationally depends on the kind of support they receive as individual creators and as members of their associations.

Is the role of a diplomat intertwined with that of a poet? How has your long living and working experience abroad been imprinted on your literary ventures?

Though also conceived as a disorder, bipolarity makes the world go round. People may be familiar with this particular condition from celebrated instances that include George Seferis, Pablo Neruda, and Octavio Paz. There is a textual connection, in fact, considering that the word “diplomatic” in the sense of international relations evolved in the eighteenth century from “diplomaticus” in modern Latin titles of collections of international treaties, where the word referred to documents and charters, from Greek “diploma,” which originally meant paper folded double. Such a double or twin predicament could describe diplomacy, as those exercising it must represent their country wherever they are accredited, while also presenting the host country back home. Poetry is a country of the sounds and meanings of words. Poets are those who try to represent it to an outside audience. Writers live in a language (or sometimes in more than one), which is their home and exile simultaneously.

In 1986 you suggested that “modern Greek culture may be considered paradigmatic… [representing] the fundamental impulse of modern cultural life…” How would you comment on the modern Greek experience 30 years later? What is Greece’s place in world imagination today?

We constantly rewrite the past in an effort to get ahead of the future. The complex – rewarding as well as frustrating, utopian as well as dystopic – relation Greeks have to their past remains of paradigmatic interest to those struggling to make sense of their lives. Moreover, much of the crucial vocabulary for thinking and acting these things through – from politics to physics or metaphysics and from theory to practice – first evolved in Greek or in subsequent interaction with it through neologisms. As a country of the imagination and a widely recognized point of origin, Greece is a place where you can discover yourself and the world. The gift involved in this is immeasurable. But so is everything that goes with it, as out-of-size gifts tend to make life difficult.

* Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE