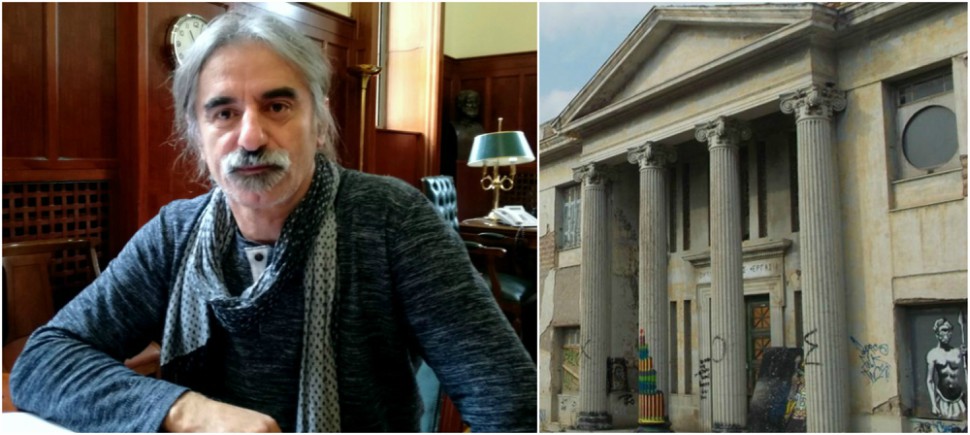

The Athens School of Fine Arts (ASFA) is Greece’s most renowned and oldest University in the field, as well as one of the country’s oldest higher education institutes in general, with a history almost as long as that of the Modern Greek state. In 2017, ASFA actually celebrated its 180th anniversary. On this occasion, Greek News Agenda spoke* with Panos Charalambous, Dean of the Athens School of Fine Arts since 2014, about the School’s past and its current significance within the contemporary art scene.

Professor Charalambous is an acclaimed artist who has worked with various materials, sometimes -especially in the past- taken from the context of Greek provincial life, and has experimented with many forms of visual and performance art. He attributes his personal style of expression to both his rural upbringing as well as to his ASFA teacher, visionary artist Nikos Kessanlis; he also considers his training in Italy as a highly formative period in his life. In his view, artistic expression constitutes a conceptual articulation, which has to take historical and social experience into account.

At the ASFA’s 180th anniversary celebratory event, you stated that “art in Modern Greece exists because the Athens School of Fine Arts exists”. Could you elaborate on that?

At the ASFA’s 180th anniversary celebratory event, you stated that “art in Modern Greece exists because the Athens School of Fine Arts exists”. Could you elaborate on that?

There is an incident described by Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his memoirs regarding a show trial in the USSR, at the time of the Great Purge; a priest under trial is asked how he can prove the existence of God, to which he responds that, since there are temples, there is God. So, taking into consideration that the Athens School of Fine Arts was established just a few years after the founding of the Modern Greek state itself, it is demonstrably responsible for shaping art in the country – and I’m not just referring to its positive qualities. This institution, having gone through many different stages and, at all times, having some of Greece’s most representative artists as teachers, managed to successfully cultivate the talent of many young people.

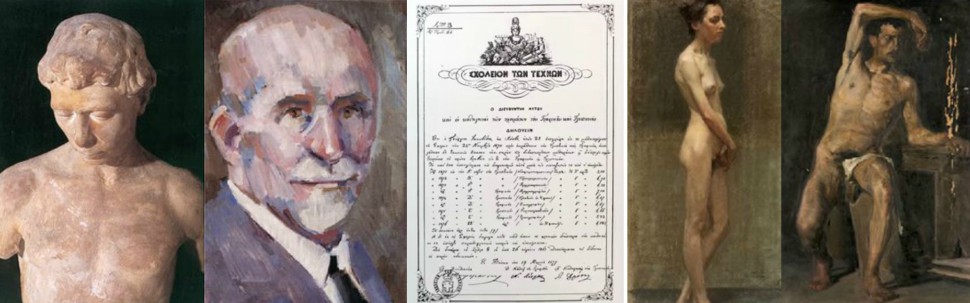

Of course we cannot deny the existence of some dominant trends and styles in Greek academic circles, especially in the prewar era, shaping the School’s profile, and some radical, ground-breaking mindshad found it hard if not impossible to be accepted there, as was the case with George Bouzianis.

So what are those stages, the phases that the ASFA went through, from an artistic point of view?

So what are those stages, the phases that the ASFA went through, from an artistic point of view?

Well, the ideas dominating the ASFA evolved in parallel to those pervading the country in general. During the Bavarian regime for instance, the mentality was to educate citizens in accordance with European standards, but the School was also supposed to function as guardian of the spirit of Classical Greece, which at the time was regarded as one of the main pillar of Western civilization (together with Roman law and Judeo-Christian values). The modernisation and westernization pursued by the government was not easily accepted by a society with a Balkan mindset, so the School of Arts was created, along with other establishments -such as the Supreme Court of Greece and the Archaeological Society of Athens- with the aim of forming a pool of people that would carry out this transition. This, I think, was the main purpose of the ASFA until WWII.

After the war, given that the world had changed and the spheres of influence were different, Modern Greek culture -manifest through the movement of the 30’s Generation– embraced a double ideal: One the one hand, preserving traditions, and on the other, seeking innovation. This was especially true after the establishment of the Third Hellenic Republic, when many teachers with a cosmopolitan outlook, such as Kessanlis, Kokkinidis, Dekoulakos and Mytaras, expressed the desire for rupture, because functioning solely as guardians of classical values was very restrictive. To this day, this continues to be our main concern as teachers: to be situated in the present time without being oblivious to the past, the multiple traditions of Modern Greece – because there is no one unique tradition. A glorious past should never be forgotten, as long as we can still be relevant to current times.

I actually endorse a view expressed by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in relation to Kafka: the dynamic of minor literatures and, by extent, minor art scenes, minor cultural scenes in general. These should not have the objective of rivaling major scenes on the same terms, but should instead try and transform their so-called weaknesses (their regionality, their small scale, their minority state) into advantages in the field of communication. Experience has proven this to be fruitful: At international fora, artists from Greece or other peripheral countries have attracted attention exactly for demonstrating elements of a national, or Mediterranean, or in other ways localculture.

I actually endorse a view expressed by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in relation to Kafka: the dynamic of minor literatures and, by extent, minor art scenes, minor cultural scenes in general. These should not have the objective of rivaling major scenes on the same terms, but should instead try and transform their so-called weaknesses (their regionality, their small scale, their minority state) into advantages in the field of communication. Experience has proven this to be fruitful: At international fora, artists from Greece or other peripheral countries have attracted attention exactly for demonstrating elements of a national, or Mediterranean, or in other ways localculture.

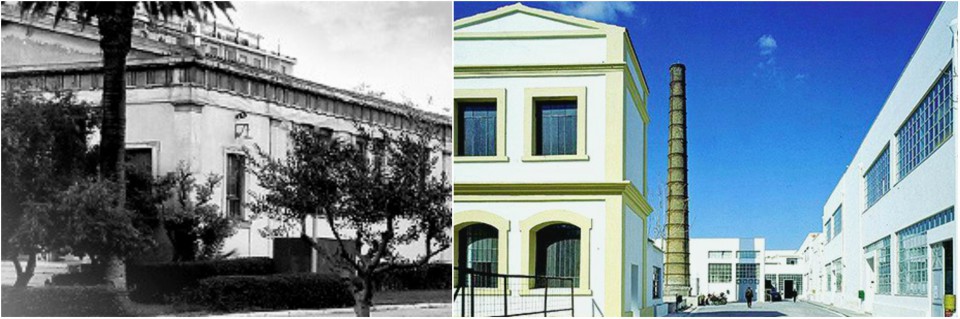

Did ASFA’s relocation to its current premises (on the grounds of a disused textile factory) also contribute to this change of the institution’s character?

It was an initiative of Nikos Kessanlis, who had very strong views on the issue, from an architectural point of view. First of all, the historic Polytechnic School compound, with its neoclassical buildings -a generous offer by past public benefactors- was deemed by then too small (2,5 km2) to accommodate the functions of the School. At the same time, on account of the plunge in industrial production in the 80’s, there were several abandoned buildings in areas like those around Pireos Street.

Kessanlis, a cosmopolitan with studies in architecture and building restoration and with experience from other European countries on the decentralisation of universities, had this idea of laying down a new connection between the classical past and contemporary sites blessed by human labour. So we didn’t lose the classical aspect whilst we gained in terms of available space, not just halls but also open spaces, where students could work under direct sunlight, experiment with techniques that require large spaces, such as action painting etc. Some, then, complained about what they perceived as loss of a more intimate environment, the sense of a “nucleus”, but I think that advantages have counter-balanced possible losses. We can’t be cut off from international trends pointing in this direction. My personal aspiration, which actually coincides with the approach generally adopted by the School’s faculty, is to establish a meeting point between Classical and contemporary art. It is a matter of talent, adaptability and perceptiveness.

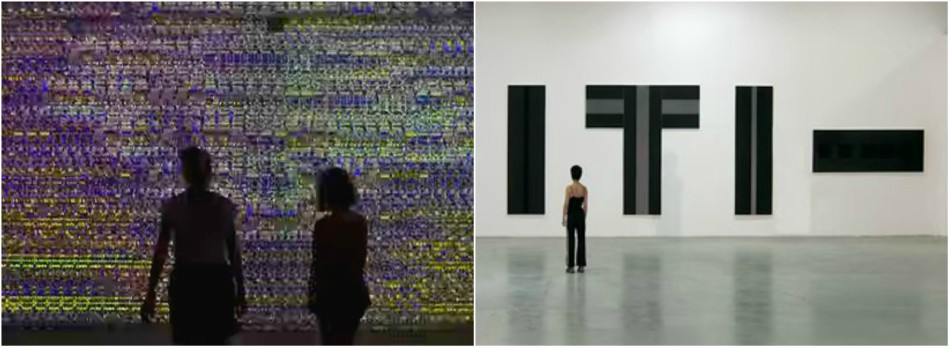

The Masters Course “Art, Virtual Reality & Multi-User systems of Artistic Expression“ was founded in 2011, in collaboration with Paris 8 University. In your opinion, could digital arts replace traditional art forms in the future?

The Masters Course “Art, Virtual Reality & Multi-User systems of Artistic Expression“ was founded in 2011, in collaboration with Paris 8 University. In your opinion, could digital arts replace traditional art forms in the future?

Personally speaking, I am not alarmed by the increasing use of technology in art; it is just an issue of techniques, a transition, auxiliary patterns that help people better understand the world around them. Art is the field of intuition, but as long as these technical interfaces help expand this field, there is no reason to be afraid. The only case where concern would be justifiable is when any stance -whether it be technophilia or an attachment to the past- culminates in doctrinism.

In order to exist in the present (which constitutes a continuum linking past and future) and not be caught between extremes, synthesis would be the best way to go: maintaining a balance so as to not be overly taken with either technology or nostalgia, given that they both have their positive and negative sides. I am not talking about keeping completely equal distances with each of the two extremes at all times, but rather about being flexible, versatile, “dancing” -if I may say so- between the two. Because, for instance, I do support cases of artists deeply committed to some old form of art; unlike science, where using obsolete tools is disastrous, in art an ancient instrument can be poetically transposed to the present and actually be functional – but it takes talent.

What about Greek art in particular? Does it have a distinct identity? You mentioned the Generation of the 30’s, a movement in quest of the meaning of “Greekness”…

What about Greek art in particular? Does it have a distinct identity? You mentioned the Generation of the 30’s, a movement in quest of the meaning of “Greekness”…

This question has been posed by every generation in some way since the foundation of the Greek state – more imperatively so at the beginning of the 20th century. This country cannot be clearly grouped with either North or South, East or West; both its geographical position and its history define it as a crossroads, a passage, like an expanded port. Contemporary Greek art does exist, and I believe in it, as I believe each place deserves to have art that expresses its particularities. There are international trends, big markets and megastars, and then you have this particular type of local artist, who owes his singularity not to being secluded in a place, but to his ability to efficiently communicate with it.

My experience abroad has taught me that, when all you do is replicate grafted foreign styles and patterns, you don’t really resonate with an international audience. This was the case with Young British Artists, when suddenly identical movements started popping up everywhere in the world. Art is not just a bundle of patterns, it’s a conversation; when you can make an actual conversation with the other cultures on a certain level you will see they need you just as well as you need them. This is what art is about, exchanges, transformations.

The issue of “Greekness”, as it has come to be known, does pose a burning question that has lead to polarising positions, with some becoming overly attached to an idealised notion of nationality, carried away by poetic fervour, while others demonstrate a desire for rupture, identifying themselves as nationless “world artists”. Both approaches have their own appeal, but extremes work better in theory than in practice…

The issue of “Greekness”, as it has come to be known, does pose a burning question that has lead to polarising positions, with some becoming overly attached to an idealised notion of nationality, carried away by poetic fervour, while others demonstrate a desire for rupture, identifying themselves as nationless “world artists”. Both approaches have their own appeal, but extremes work better in theory than in practice…

I would also like to ask some questions regarding the Athens School of Fine Arts more specifically: could tell us something about its famed annexes, called “Artistic Stations”?

These annexes, workshops situated in various regions throughout Greece, were an initiative that began in the 1920’s, inspired by a desire to bring students closer to the Greek landscape, both natural and cultural. We now have eight of them, and intend to open more. Their function will be enriched in the future, with the function of summer schools etc. Their operation has been very successful, with a great number of participants from many foreign institutions, with which we have ongoing collaborations. Participants are truly thrilled with the experience, the chance to work close to nature, in an idyllic environment.

I must point out that the annexes have been, in great part, the result of donations and sponsorships. Benefactors have contributed a lot the School’s expansion, as was the case with our library, recently renovated with the support of Niarchos Foundation. We also have received support from NEON organisation, and other expansions have been planned thanks to future donations announced by the Contemporary Greek Art Institute, Eleni Vernadaki and others. In difficult times, there are many Greek private institutions that have helped in the domain of arts.

I must point out that the annexes have been, in great part, the result of donations and sponsorships. Benefactors have contributed a lot the School’s expansion, as was the case with our library, recently renovated with the support of Niarchos Foundation. We also have received support from NEON organisation, and other expansions have been planned thanks to future donations announced by the Contemporary Greek Art Institute, Eleni Vernadaki and others. In difficult times, there are many Greek private institutions that have helped in the domain of arts.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi

Read more on Greek News Agenda: Athens School of Fine Arts celebrates 180 years; Katerina Koskina on the need for cultural dialogue & EMST’s role as an arts capsule for the city branding of Athens; Denys Zacharopoulos: A museum should function as an open window between the private and the public life of people; Alexandros Psychoulis on the idea of symbiotic bliss & the reality of working as a visual artist in Greece; Gary Carrion-Murayari on “The Equilibrists” & the contemporary arts scene in Greece; Efi Kyprianidou on Art and Compassion

Watch a short documentary specially created for ASFA’s 180 anniversary (in Greek):