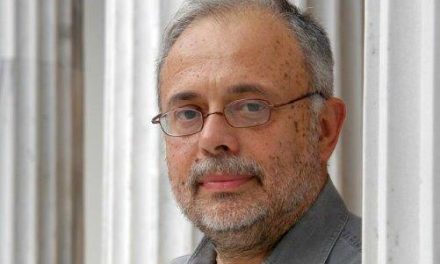

Paganistic, loving life, humorous and boasting a unique filmic style, Dimos Avdeliodis’ films have left their imprint on Greek Cinema. Actor, playwright, film and theatre director Avdeliodis was born in 1952, in Chios, Greece. He has directed four highly acclaimed feature films, among which “The four seasons of the Law” (1999) has been repeatedly voted by Greek film critics as one of the best films of Greek cinema. Avdeliodis has taught film studies at Panteion University (1993-1998) and has also served as Head of Municipal and Regional Theatre of the North Aegean (1997 – 2000, 2003 – 2010). Through some twenty plays that he has directed he is continuously experimenting with new creative theatrical routes.

Avdeliodis told Greek News Agenda* that what drove him towards these art forms was the need for self exploration. He talks about his relationship with the island of Chios, his birthplace, explaining that giving Chios a leading role in his films was a repayment for the gift of beauty that the Island has given him. He stresses that art plays a unifying role and underlines the humanistic aspects of Greekness in his work.

You are a theatre and cinema director and actor, and also engage in a range of related creative activities. What has driven you there?

What primarily drives me in art is mainly the need to get to know ourselves. This is a question that concerns everyone, not just the artists. The question that either tortures people or gives them hope relates to who they are, why they are and what the purpose of their existence is. This everlasting question has not yet been answered, because if it had we would’ve felt much better. However we don’t, because we have wasted a lot of time without answering this question. This question was initiated by Socrates and remains unanswered. So, the reason why, I believe, we are dealing with art is precisely to try to answer such questions. Art gives you the freedom of choice not only of the subject, but also of how work on a subject. Art naturally involves inspiration and talent. Inspiration is momentary, short-lived. Giving content to inspiration requires a rational procedure, a structure. Through art we can make the necessary corrections to communicate with others and see if we agree and find out if we all want the same thing. In case we don’t, what do I propose? I feel a great urge to communicate with other people on this basis.

Jannis Avdeliodis, Nikos Mioteris, “The tree we hurt” (1987)

In your films “The Tree we hurt”/ “To dentro pou pligoname” and the emblematic “The four seasons of the Law”, the island of Chios is a central character. What is the role of Chios, your birthplace, in your work?

The relationship everyone has with his birthplace is purely personal. You either love or hate the place where you were born. Unavoidably we are shaped by our birthplace, so Chios, for me, is essentially my mirror. It was where I perceived my first images and sounds. I therefore made those two films as a repayment for this gift I received from Chios. It was such a generous gift that I wanted to pass it on to others, and by doing these films I was released from this weight of beauty. I wanted to relive only the pleasant experiences of my past and omit the ugly. This means that I’m not interested in nostalgia that is accompanied by pain. I revisit a scene to see it critically in order to be able to make corrections in my present life. This has always been the criterion for these films. Nostalgia is of course very important to human beings. Everyone wants to go back to their childhood, but that is impossible. Therefore, the only thing you can gain from this return is to restructure your current reality correcting the past.

What does art have to offer to people?

Here is what is amazing in art: A work written about 2,500 years ago or more will not wear out with time, as is the case with Medea by Euripides. I remember when reading Medea, it felt so contemporary. I do not think that any playwright could do it better today. The purpose of art is not to teach new things but to make us feel things. Experiencing feelings together with other people is a very important event. This makes art a unifying power, it connects people. In everyday life we tend to miss the profound importance and influence of art, whose role is to help people, to capture timeless human ideals. Who doesn’t want to be happy in life or help someone else when that gives him joy? Greek civilization has forged these values in all the forms of knowledge it has bequeathed us, from politics to art and the sciences; it is deeply humanistic, aims to help people attain happiness through knowledge and creativity. This is the gift of Greek antiquity.

“The trackers”, dir. D. Avdeliodis (2010)

The concept of going back to the past is central both in your films and plays; going back in time and place. Do you feel uncomfortable with the present? Do you feel uncomfortable in the city you live in, the metropolis?

Not at all; this has only to do with the fact that I worship these works and I believe that they take an event, a horrific event at times, and transform it through art. For me it is clear that the patriarch is Homer, the originator of art. He set the canons to which everyone in Western culture and all around the world adheres. All cinematic and literary tricks are there in Homer’s oeuvre. The first imitators of Homer were the masters of tragedy. At a time of uncertainty, during the Peloponnesian War, they created drama, which is still the standard today, and these works continue long after with Hortatsis, essentially a child of Homer, who created the Cretan Renaissance, and his pupil and successor Vitzentzos Kornaros. They were all equally great masters. Along came Dionysios Solomos, who followed the same path, with Vizyinos and Papadiamantis afterwards at roughly the same period. These are the great masters that manage art as a tool to convey the excitement of life and how they can control or transform what happened in the past.

How do you feel about young people today and their creative efforts in the conditions of the crisis?

I’ve seen a lot of great things and the only certainty is that every generation tries to give its best; and it will give their best. We have to point out that these kids have been deprived of an essential education. We lived in the 80’s in the virtual reality of television which shaped what we are seeing today. The kids who resisted this TV culture are the ones moving forward.

What is role of Religion in your artistic conception?

Religion has not concerned me much, in the sense that it is self-evident that in the Orthodox culture we lived and grew up in, it works fine to say “I’m very pleased to be an Orthodox” and sometimes not. We all know that; it’s in our culture, so I did not focus on religion. The way I experience religion is on the basis that you have to do what’s good and that all people are essentially the same. When we do not know someone, we are afraid, but when we get to know them, we understand that they are not as bad as we thought. And really, since, all humans have been made by the same creator, how is it possible to make good and bad people?

“The Woman of Zakynthos”, dir. D. Avdeliodis (2015)

Through your work you try to compose your own definition of Greekness.

Greekness, as I have said, does not concern Greeks alone but mankind in general. It cannot be restricted within the boundaries of Greece, neither as an area nor as a nation. It was solidified in the golden age of Pericles and has a strictly humanistic purpose to find human happiness. This is my definition of Greekness.

You taught film studies at Panteion University from 1993 to 1998 where you chose to teach Aristotle’s poetics. Why was that?

I followed the translation of Aristotle’s Poetics by Ioannis Sykoutris. For me Poetics is the most important work of Sykoutris. Poetics is the most complete definition of art and its purpose; it is the Bible of art. Thanks to Sykoutris, I could finally understand why naturalism failed in theatre. There were no naturalistic elements in ancient theatre. It does not have physical elements, no naturalistic elements that is, at all. It was no coincidence. Theatrical conventions entailed the costumes, the masks and the voice of the actors. No one knew who was behind the mask. Death, murders, war and battles never took place on stage. They didn’t want to show these on stage. They wanted to forget that through art; and that is wanted to teach my students.

Jasmine Kilaidoni, ” Maran Atha” by Thomas Psiras, dir. D. Avdeliodis

Your direction of plays such as “Figures from the work of Viziinos”, and more recently Thomas Psyrras’ “Maran Atha” have been critically acclaimed. Your work with actors is based on a method you have elaborated. Could you describe it?

When working as theatre director my experience as an actor was very helpful. What is the art of acting, I asked myself. I slowly learnt how to manage the way an actor handles each phrase, so I elaborated a method of teaching the actor how to recite each phrase keeping a logical musical line. I focus a lot on the tone of the actor’s voice; by changing his or her voice, the actor can play many characters. Each phrase, each word must be stressed in such a way so as to transmit a certain frequency. There must be the correct rhythmic change, the elasticity of every phrase, in order to make sense. As a result, the audience may hear Viziinos or Papadiamantis in the katharevousa (pure, formal Greek) and it doesn’t feel difficult.

“Alexander the Great and the damned Dragon”, dir. D. Avdeliodis (2010)

Was your “Alexander the Great and the damned Dragon” a children’s play?

I do not believe in children’s theatre. A theatre that is especially for children, most of the time tries to explain things to children, because there is the notion that children should be helped to understand what may be difficult concepts. This is a mistake, however, because children understand everything. There is no way you can fool a child. You may be able to deceive an adult, but you can never deceive a child. Therefore, it is better for a child to see a good show aimed at intelligent human beings, even if he doesn’t understand everything. In art we are interested in what the child feels.

Read more: Greek theatre tradition, Twentieth Century Greek Theater

* Interview by Florentia kiortsi and Kostas Mavroeidis.

** Special thanks to Angeliki Spyropoulou

Watch the film “The tree we hurt” by Dimos Avdeliodis: