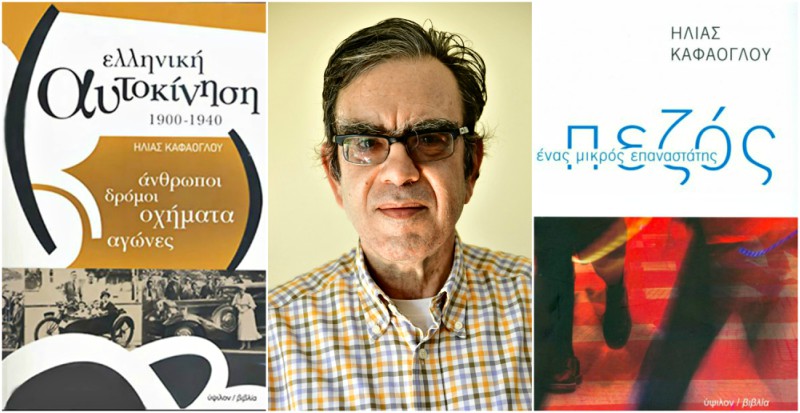

Elias Kafaoglou is a writer and journalist. He has penned a number of essays and studies on themes ranging from Modern Greek literature and history to cars and foortball. Apart from his books, his literary and other articles have appeared in various magazines including 4WHEELS, Diabazo, Porfiras, I Lexi, and others.

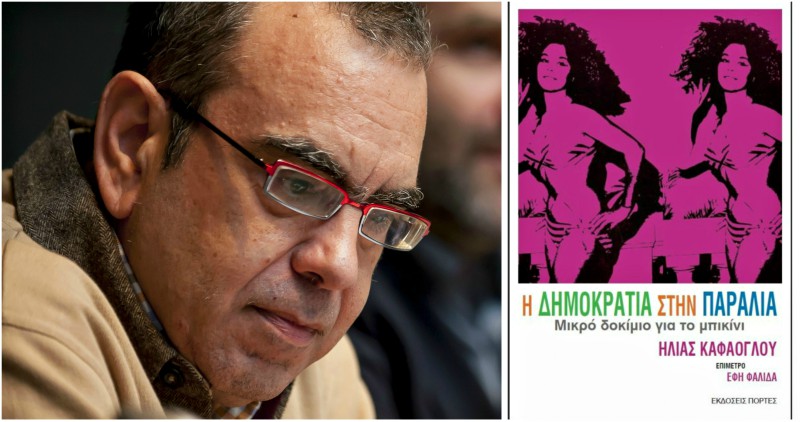

Some of his most recent works include Greek Motoring 1900-1940 (2013) and Pedestrian – A little rebel (2016). In summer 2018 he published his latest book Democracy on the beach – A small essay on the bikini, where he the history of the famous two-piece swimsuit , especially focusing on how it was received in Greece – by everyday people, the religious conservatives, the militant Left, but also artists or the Press.

Greek news Agenda interviewed Kafaoglou* on his latest books: automobiles, the bikini and, now, digital technologies, all form part of the modernisation taking place in recent history and are thus directly linked to the very concept of democracy.

You have worked in several media, including specialised magazines such as 4WHEELS. To what extent has this experience affected the choice of subject of your books?

My work as a journalist for specialist publications did not influence my choice of subject. My engagement with the history of Greek motoring, the way Greek society perceived it, began prior to my involvement with the magazines in question. Nevertheless, the mood generated by these specialised magazines contributed to connecting the examination of motoring with the focus of my work, via discussions with older colleagues. In any case, the research on the evolution of motoring in Greece in the interwar years essentially began from scratch, since the first systematically documented work in this area, extending through the post-war years up to the 1980s, was published in 2009.

I’d say that the publisher of the Express newspaper, Spyros Galaios, was responsible for my involvement with this research. I had only just been hired, when he asked me to describe, in writing, a pencil like a car; to devise a car from a pencil! And that is how my motoring and mobile world was initiated on paper.

Your book Greek Motoring 1900-1940 is an in-depth study of a subject that had not been broached by anyone in Greece. Why did you choose those dates in particular? In your opinion, when did Greek motoring really begin to develop?

Right from the start, motor vehicles have been identified with progress, speed, free and liberated spirits. It is a token and hallmark of modernity, and it was received as such by Greek society. It is precisely this reception that I am interested in, mainly in the Greek interwar years which were a time of ‘shy modernity’. The first period of Greek motoring refers to the time from its beginning to the Balkan wars (1912-1913). It seems that the first car in Athens appeared in 1894 or 1898. In 1905 we have the first road surfacing in Athens and, thanks to George Theotokas, the city’s emblematic Syngrou Avenue was carved for construction. In 1905-1906, we have the first automobile makers, four years later the first car in Thessaloniki makes its appearance, then the first car dealers, whilst drivers are car engineers as well.

The needs of war preparations in 1912-1913 changed motoring radically: automobiles were ordered, some of them of the latest technology, and many cars together with their drivers are recruited. As early as 1913, a Car Office was established and the first driver’s license was issued, while Greek engineers were performing miracles in opening roads so that the artillery could be reach firing position. Thus we cannot understand Greek motoring trends, its course in time, without studying the use of motoring in Greek military operations. After the Balkan Wars and the incorporation of new territories, the domestic market expanded, motoring gradually became part of the public consciousness, and new transportation needs are put on the table thanks to the modernisation program of then Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos.

One must also take into account the role of the Allies who settled in Thessaloniki during the First World War. Allied troops built a 900-km-long road network and left behind more than 600 trucks in Thessaloniki, whose buyers essentially provided the material for the first car dealerships. However, the decisive move towards the Greek Army’s automation and thus the wider spread of motoring took place during the Asia Minor expedition, as by June 1921 the Army engaged approximately 2,500 vehicles in various formations served by 500 officers and 3,000 soldiers.

Science and technology, as we move towards Venizelos’ four-year term in 1928-1932, becomes crucial and integral to the priorities of politicians, intellectuals, engineers and contractors of the Technical Chamber of Greece (TEE), founded in 1923, the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA), as well as the Automobile and Touring Club of Greece (ELPA), which was founded in 1924 and operated alongside the Ministry of Transportation that was established immediately after the Balkan Wars and made use of the experience of ELPA’s 117 entrepreneurs and academic founding members. On May 25, 1928, speaking at the Liberal Club of Athens, Venizelos expressed his intent to transform Greece through motoring and the construction of a national road network, with automobiles serving as lever for growth, a target also proclaimed in Parliament. Beyond that, from 1936 onwards, everything became subject to war preparations. It is precisely this line of developments that interested me, and doing research is always such a blissful exercise.

Many writers and thinkers, such as Honore de Balzac, Arthur Rimbaud, even Demosthenes referring to Nikovoulos, have made reference to the importance of walking. Would you like to tell us about the designation of the pedestrian as a “little rebel”?

Many writers and thinkers, such as Honore de Balzac, Arthur Rimbaud, even Demosthenes referring to Nikovoulos, have made reference to the importance of walking. Would you like to tell us about the designation of the pedestrian as a “little rebel”?

The primarily public space of a city is its streets, avenues which render a city with perspective. I think streets educate the eye, signify a passage and, at the same time, a transition. They consist and recommend places and landscapes of collective memory and individual experience. I like claiming my right to the city, which I, a lover of automobiles, do not like to watch through the windows of a car, with fleeting glances of successive frames. I like to walk, to feel the ground with every step, to compose the sequence of steps and moves on the pavement, and thus rewrite again and again public space as my own space; Being a passionate walker, to write about it with my very own limbs. Pedestrians, I think, step by step, pay tribute to carefreeness, leisurely movement and the unhurried passing of time in a world that runs at high speed. When walking, we are exposed to the winds, like children and lovers. Thus, pedestrians by conviction become little revolutionaries.

How is it that you dealt with an issue such as the two-piece swimsuit, the bikini? How is the bikini related to “democracy on the beach”?

At first it was Nikos Engonopoulos and his poem “A hymn of praise to the women we love”. I once wanted to be able write something about the women I loved and I love, my “harbors”, our “harbors”. Then, the sand… The traces of bodies are erased by the sand, cracks in the sands of words by the winds, in the sand, the land of oblivion, bodies lose their memory. Bodies in the sand signify – the memory of silence annihilates the silence of memory.

What are those girls lying down on the sand that I was observing trying to tell me dressed up in their passion? Wearing their two-piece swimsuits, frontier zones, what were they trying to tell me? Then the glances that I felt, like hands touching, shelters of dreams; how could an object of the material world pose questions in its time? How was it received in its time? How did Europe react to the bikini, during the ‘Golden Hundred Years’ of mobilisations and counter-culture, the children of Marx and Coca-Cola?

The Bikini was introduced on July 5, 1946, thanks to a French automobile engineer, and of course thanks to the materials and skills required. Let’s not forget that the appearance of the bikini made headline news, four days as it were after an atomic bomb was detonated over the Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands as part of nuclear testing by the USA. It became an emblem by which women could show their bodies – and in this respect, it is the absolute symbol of social distinction, since women have to spend money to maintain bodies suitable for a bikini, a measure for perfection, consistent with ‘sculpted bodies’.

Thus bikinis are sexy and revealing, they intrigue male fantasies, they are inseparable from beach culture and emblematic of carefreeness, youthfulness and comfort. A bikini highlights deadly beauty but also unites and divides, since it both compels respect towards the female body that it draws attention to, makes the body on the beach desirable but from a distance; It is a case of style, but also a prominent statement of freedom. Thus, the bikini signifies democracy on the beach, the democracy of glances out there.

What is the character of your study (cultural, sociological or anthropological) and the theoretical model that structured it?

Women choose to be dressed according to their time, in the context of particular social associations, and the bikini is associated with the post-war women’s liberation movements as well as with youth as a distinct category with purchasing power striving for independence from their parents.

Following World War II, the “consumer revolution” moved to Europe, the right to free time was reinforced, the right to paid leave was attained, and beaches in the Mediterranean were filled with crowds, thanks also to the spread of motoring. Youth culture during this period becomes a kind of global trend. Young people have fun, rebel, fall in love, declare and defend their own identity in Europe and Greece. In this context, the rise and widespread dissemination of the bikini is viewed through the lens of historical studies, as well as of cultural and social and mobility studies, a new field of social sciences.

Your essay depicts the two-piece swimsuit as a revolutionary icon of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s. What was the attitude of Greek society towards the bikini at the time?

Your essay depicts the two-piece swimsuit as a revolutionary icon of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s. What was the attitude of Greek society towards the bikini at the time?

The bikini’s reception in Greece was similar to that of rock and roll: both progressives on the left and religious conservatives reacted with caution, if not outright denunciation, at a time of steady economic development as well as of pounding for the formation of a nationalist conscience. It was an era of social movements and popular demands, activism for education, with youth at the forefront becoming an independent political factor that transformed public places into ‘protest space’.

“Moral decadence”, young people’s choice of dress, the management of their bodies as they wished, the long hair and the bikini all became troubling and disturbing, creating ” moral panic ” at a time when the country was on the way of developing its tourist sector and year after year a greater number of its people connect with the sea for recreational purposes, an area ignored until then in Greece. The bodies on the beaches in Greece by the late ‘50s had become signifiers, carriers of meanings that gradually shaped their own priorities as one could clearly see in cinema, literature and in magazines. Fashion of course was urging women to follow its trends on the beach as well. Let us however consider what a girl in the Greek countryside would do; would she wear bikini to show off her beauty or would she be cautious, with this hesitation preventing her from doing so?

Would this young woman follow the bikini trend so as to become desirable / accepted by other young people, or would she follow the traditional path and not expose herself? The young visitors to Greece urged her to undress in order to be trendy, but her role as a future spouse discouraged her from that direction. Besides, western consumer models and fashion trends, idleness and laziness were all identical to the conservative journalists and their leading ideological discourse of the time, while the new dress code signified differentiation, the demand for independence and the aim to become part of a different collective structure other than the family and its traditional standards. Thus the bikini can be an excellent vehicle for discussing the dividing lines within the collective behaviours of social formations in the years up to the dictatorship (1967-1974). Individual passions often set the tone on the beaches -and not only there- in the years before the May 1968 events (in France) and after that in the years of the so-called “missed spring”.

What is your view of fashion – does it follow or shape social trends?

Fashion shapes its own demands in society and society poses its questions to fashion. Mary Quant, André Courrèges and Vidal Sassoon brought fashion out in the streets, but the main attire during student mobilisations was not the mini, but jeans, the chief dress code of politicised youth.

How do you see the evolution of morals and of generations over the last two decades in relation to the massive technological revolution that has been shaping “digital beings”? Are there any signs of doubt, of new subversive visions?

The democratisation of desires is what I’d like to hold on to from the “digital age”. It is enough to yearn for our equals and companions in life, and to hope, because then we are ready and complete. Do we know how to live by allowing others to live? That is the challenge. Obviously, our own future lasts long, written in a digital environment, although I personally am in love with blank writing paper because there are always moments and places and people waiting for those who need and deserve and crave them; because parties of friends make history.

*Interview by Marianna Varvarrigou

Read also in Reading Greece: Alexis Panselinos: “A writer must stand courageously in front of the mirror that is his art”; Writer Vangelis Raptopoulos on “The man who burned down Greece”