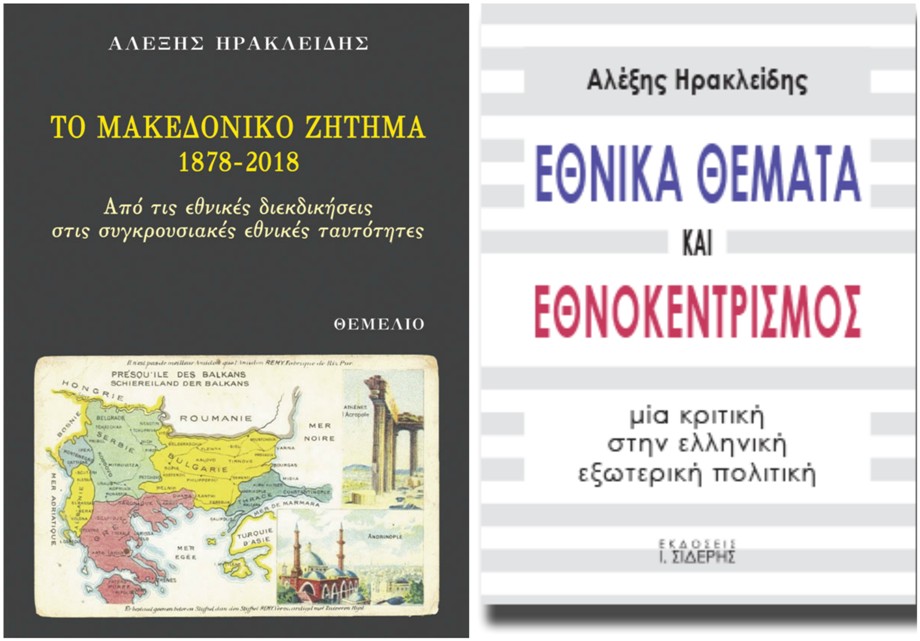

Alexis Heraclides is Professor of International Relations and Conflict Resolution at the Department of Political Science and History of the Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences. He has served as senior advisor on minorities and human rights at the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1983-1995) and has written about seventy papers in scholarly journals, as well as six books in English and thirteen in Greek, including, The Self-Determination of Minorities in International Politics (1991), The Cyprus Question: Conflict and Resolution (2002) [in Greek], The Greek-Turkish Conflict in the Aegean: Imagined Enemies (2010), and with Ada Dialla, Humanitarian Intervention in the Long Nineteenth Century: Setting the Precedent (2015).

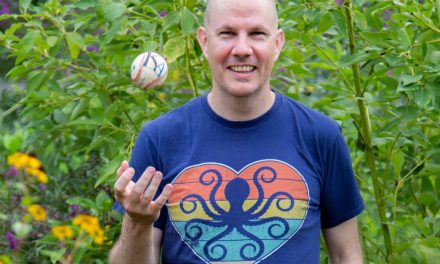

As a public intellectual Professor Heraclides often contributes to the debate on foreign policy issues in Greece with his -often considered controversial- opinion articles. Ηis most recent intervention was the publication of two books; one that offers an overall assesment of the Greek foreign policy (“National Issues and Ethnocentrism: A Critique of Greek Foreign Policy, 2018, in Greek) and one that provieds a historical and political review of the Macedonian issue (The Macedonian Question 1878-1918: From national claims to conflicting national identities” 2018, in Greek).

Professor Heraclides spoke to Rethinking Greece* about foreign policy formation in Greece on the basis of “national issues”; ethnocentrism as an obstacle to the resolution of these issues; Greece’s historical advantage as the fisrt country in the Balkans to become an independent state; the difficult future of Greek-Turkish relations post-2015 Erdoğan; what he foresees in the Cyprus issue; his assessment of the Prespes Agreement as favorable for Greece and finally, the importance of establishing a secure national identity for the country, grounded on Greece’s very worthwhile cultural and scientific contributions to the modern world.

Why two books, one Greece’s ‘national issues’ overall, and another for the “Macedonian Question” in the current conjecture?

“National issues” is a term routinely used in Greece, although in my research I found out that to a considerable extent, the term is also used in a similar manner in Turkey. In other countries, for example in the Philippines or India, ‘national issues’ refer to poverty, illiteracy, corruption and so on, that is issues that are of a domestic nature. Understanding foreign policy issues basically as national issues is the reason why Greeks have paid an enormous economic and diplomatic capital to defend these issues, and have done so, most of the time unsuccessfully, based on misperceptions.

Whenever a ‘national issue’ comes to the fore, like Cyprus Issue, the Aegean, or the Macedonian Question, it becomes very emotional, deeply affecting the Greek public and this does not permit the government in charge -or the opposition- to be more rational and balanced in its approach. If you want to succeed in foreign policy-making, you should go about it in a rational manner (the ‘rational actor model’ as it is known in foreign policy analysis), trying to limit the costs and increase the gains. However if emotions prevail, it is very difficult to do so. I think that the key reason for this malaise, which I used in my book on national issues, and which also pervades my book on the Macedonian Question, is “ethnocentrism,” namely Greek ethnocentrism.

Ethnocentrism is a concept conceived by William Graham Sumner, an American sociologist, more than a hundred years ago. It means that you regard your nation as the centre of the world and this applies to your viewpoint, that it is beyond reproach; and all the other nations are seen from this ethnocentric perspective and by and large in a negative light. And there emerges a kind of hierarchy: the adversaries are not worthy; they are morally and culturally inferior and so on. You obviously cannot solve a conflict if you regard your nation or state as being always on the right and just, and the other side by definition wrong, unjust or aggressive. I believe that ethnocentrism is the main reason why Greece has allowed all these ‘national issues’ to be with us, for decades, unwieldy, painful and unresolved.

My basic point is that if Greece resolves these questions, as hopefully is now the case with the Macedonian question, with the June 2018 Prespes Agreement, if it resolves its so-called national issues, it will come to be regarded as a very responsible, constructive and mature state in this region of the world and it will be able to attain ‘soft power’, and most important of all earn the respect and friendship of its neighbours, which is now in short supply.

With the outbreak of the crisis in Greece, foreign policy issues took a backseat, as financial and economic issues monopolized the scene. This has changed in recent years with the Macedonian and Cyprus issues as well as the Aegean back on the agenda. What is your view about the level of public debate in Greece on these issues, by both journalists and experts in international relations?

The level of public debate is disappointing, though it is an improvement by comparison to previous decades, for instance as regards scholars who had been previously anti-Slav-Macedonian, some of them have switched their position. This is probably due the fact that the previous foreign minister, Nikos Kotzias, was able to convince some nationalists to accept the solution of the Macedonian issue as an ‘honourable compromise’. Some nationalists also happen to be pragmatists; they realize that if you have an unresolved issue since the early 90s, and 150 states have already recognized this country with its constitutional name (“Republic of Macedonia”) time is not on the side of Greece.

At the end of the day, the basic thrust of most Greek (or Greek Cypriot) nationalists is that if we are more patient, and wait a bit longer, the time will be ripe for ‘us’ to gain all that our heart desires on national issues. As regards Turkey and Cyprus, the ultra-nationalist Greek argument runs as follows: since president Erdoğan and Turkey are getting themselves into more trouble by the day, and there is also the awesome Kurdish issue to reckon with, at some point Turkey will become weaker, it will collapse and split into two or more parts (with the creation of a Kurdish state in the east). This would be the ideal situation for ‘us’ to have the whole of Cyprus (after all ‘Cyprus is Greek’ according to a well-know slogan). My counter-argument to the ultra-nationalists is that Turkey´s disintegration is highly improbable; but if, for the sake of argument, we accept this far-fetched scenario, a future smaller Turkish state would still be still be a very large state -60 million strong- still with geopolitical clout, given its geographical position; without the Kurds, it would be more cohesive, with a vibrant Turkish national identity and therefore, even more threatening to Greece. However, may I point out that in many scholarly works on Greek-Turkish relations and in my many articles in the press from the mid-1990s onwards, I have repeatedly pointed out that, until very recently, Turkey was not threatening towards Greece and had no aggressive or expansionist tendencies towards Greece. The so called “Eastern Threat’ was a Greek self-serving myth.

Another area where things are slightly better is the question of the Aegean: for instance the Kathimerini newspaper, which is conservative but prestigious by the standards of the Greek press, has come up with a number of articles in its Sunday additions that are slightly more favourable towards a solution, and take into consideration Turkey’s concerns as legitimate interests. The real problem with the Aegean standstill and the lack of solution boils down to the fact that for most Greeks – nationalists and including even non-nationalists – is that they tend to view the Aegean as a ‘Greek lake’ or ‘Greek Sea’; they somehow forget (there again we see Greek ethnocentrism) that there is another country on the other side of the Aegean with a very extended coastline on this sea.

Nationalism has played a key role in modern European history. Do you think that Greece is more ethnocentric than other countries?

That is a good question. Greece is definitely more ethnocentric than, say, the Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands or Belgium. But there are other nations or states that are similarly ethnocentric, such as the Russians, the Serbs, the Albanians, the Slav-Macedonians, the Bulgarians, the Israelis, and certainly the Turks. Thus I wouldn’t say that the Greeks are more ethnocentric. However I would say that they are more to blame for being ethnocentric. Let me elaborate this assertion of mine. Greece was the first state in the Balkans to become independent, the first nation-state in this part of the world; all the Christians of the Balkans at the time –apart from the Serbs– wanted to become Greeks, because as ‘Greeks’, be it in the Greek state or in the Ottoman Empire, they could experience upwards social mobility, from illiterate peasants that they were initially, they could attain the status of the literate middle or upper class.

Compared to other states which became independent much later in the Balkans and the Near East, Greece is in a much better position, and thus it should have been more relaxed and confident than it is. Experts on the Balkans, like Evangelos Kofos and academics such as Christos Rozakis, Thanos Veremis, Antonis Liakos and others have pointed out that when, after the end of the Cold War, the other Balkan countries left the communist bloc, Greece didn’t promote good relations with them and instead of becoming part of the solution, it became part of the Balkan problem. This is why I am blaming the Greeks. I regard it a responsibility on my part as a public intellectual to focus my criticism on my countrymen and countrywomen, rather than to blame other peoples and states. However, in my academic publications, when studying conflicts and trying to suggest win-win solutions for two adversaries, I have treated all ultra-nationalists as the main parties responsible for these unending ethnic or national conflicts, as for instance, with Serbia and Kosovo, Bosnia, Israel and the Palestinians and other cases across the world.

As you point out in your book on the national issues, Greek-Turkish relations have been cordial during certain periods of time, therefore they are not necessarily ‘doomed’ to be always tense and in a state of rivalry. But by now a huge psychological barrier has been created between the two countries. Can it be bridged? How do you see Greek-Turkish relations evolving?

The future of Greek-Turkish relations is bleak and almost alarming due to post-2015 Erdoğan. So long as we have Erdoğan as the Turkish leader there is little chance of relations getting any better. The name of the game at the moment is mainly skilful conflict management, so that things do not to get out of hand and we end up with a clash. His role is detrimental, primarily for his own country, at various levels (government, diplomacy, ideology, culture, even aesthetics). So long as Erdoğan holds sway, no Greek national issue linked with Turkey (Aegean, Cyprus, minorities) can be resolved. But please note that the original Erdoğan was completely different, virtually someone else: he had switched Turkey’s negative position on resolving the Cyprus Problem (accepting the federal formula), he was ready to accept Greece getting more than six miles of territorial waters in the Aegean dispute, do away with the casus belli threat in the Aegean, and a more benign approach toward the Patiarchate and the Greek minority in Istanbul, not to mention his overtures toward resolving the Kurdish problem in Turkey. Not being a Turkish specialist, I have great difficulty trying to logically explain why this change has occurred since 2016 or since 2011 or 2012 to be more exact, given the fact that it is the very same person who suddenly joined the nationalist club. Previously he was not a nationalist, and as a result was supported by liberal and leftist Turkish intellectuals, as well as by many Kurds who actually chose to vote for his party, the AKP, instead of the Kurdish party. Perhaps his original posture was simply the result of him being surrounded by educated, open-minded and more sophisticated individuals within the AKP, such as Abdullah Gül, Ahmet Davutoğlu and others. At that time Erdoğan sincerely wanted Turkey to become a part of Europe, to join the EU, and he did other positive things as well, such as drastically diminishing the clout of the military. But he gradually changed, and now we have before us a mixture of follie de grandeur and corruption, and the question with corruption is, as Lord Acton had famously put it: ‘power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’. And to think that originally, Erdoğan’s party, AKP, was the ‘white party’ in the sense that it was clean of corruption, like SYRIZA is today in Greece.

Another matter is the ‘Sèvres syndrome” or ‘Sèvres phobia’, which I mention in my book on the Greek national issues. This is a kind of reflex activated in Turkey whenever things don’t turn out well at the international level: the Turks tend to blame the West for wanting to ‘dismember Turkey’, as it had happened with the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, which went as far as partitioning even Asia Minor. That treaty provided for a Turkey that would been one fourth of the size of today’s Turkey, hence the Sèvres nightmare for the Turks. They have another nightmare, which is the bygone ‘Megali Idea’ of the Greeks (the irredentist Great Idea of Greece from the 1850s until 1922). If you ask Turkish university students what they know about Greece, at a minimum they will tell you two things: that Athens is the capital, and that the ‘Megali Idea’ is still alive in Greece. As for the Sèvres syndrome, it is not a conspiracy theory of the people in the street who have no knowledge of international politics; it is taken on board by a great part of the elite, many hard-line diplomats and politicians and even by academics, and they sincerely believe it till this very day. That is indeed worrying. For if you feel threatened and cornered, however mistakenly, you may react unpredictably and aggressively.

Thinking aloud I was contemplating the missed opportunities with Turkey, and that today’s Turkey is indeed how the Greek nationalists always wanted it to be. They have always dreamt of having a Turkey as bad as the one of today, from 2016 onwards, or even worse. Imagine if Turkey had become a part of Europe, say during the mid-1990’s, it would have not reached this dismal point; the power of the military would have been limited; the power of Islam limited; and the country would have been more European and democratic than it is today. But who was responsible for not allowing Turkey to join the ‘charmed circle’ of the EU? Greece with its repeated veto throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

After the deadlock in negotiations between the President of Cyprus Nicos Anastasiades and Turkish Cypriot leader Mustafa Akıncı in 2017, what can we expect next on the Cyprus issue?

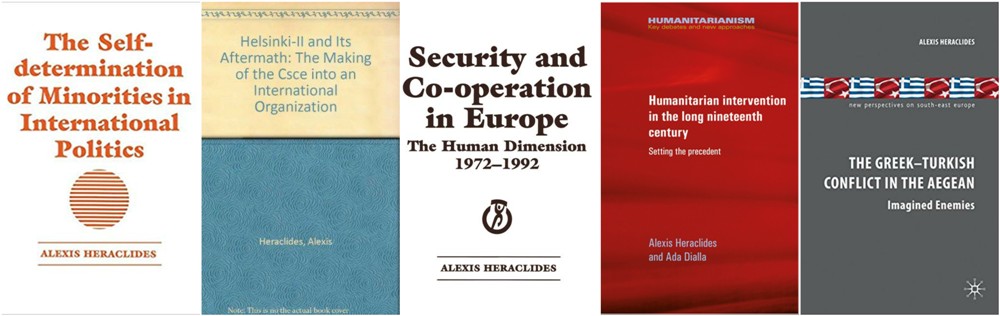

I don’t expect anything positive to happen. It is going to be Plan B, a divided Cyprus with two states, hopefully as a result of a ‘velvet divorce’ and not an adversarial one. The ethnocentric approach on the Cyprus issue is the following, among Greeks and Greek Cypriots alike: ‘“Cyprus is Greek’. If Cyprus is Greek, then the issue is never going to be resolved, for it implies that the Turkish Cypriots should either be treated like a minority, or disappear into thin air, that is leave by boat or plane to Turkey. My first ever newspaper article on the Cyprus issue (1996, newspaper To Vima) was on how to resolve the Cyprus Problem and I suggested a loose consociational federation. At the time I was attacked by some Greek hawkish academics and by officials of the Cypriot Embassy as a traitor and pro-Turkish. I still believe that the best possible solution is a loose bicommunal bizonal federation. Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots have been living partially divided from 1964, and completely divided from 1974 onwards. I know the percentages are not helpful. Given the percentage of 80% Greek Cypriots and of 20% Turk Cypriots, it is not easy for the Greek Cypriots to accept the other side as their partner on the basis of equality. However, I believe it is the only way to bring the two ethnic communities back together.

I have told the Greek Cypriots from time to time, that in a loose federation they would be nominally (legally) equal, but in substance it’s going to be more like a firm with a senior partner and a junior partner. In my opinion, given the fact that the Greek-Cypriots are richer and better educated, it is the Turkish Cypriots who have to be protected, since they are obviously the underdog in Cyprus. I would say that the problem with the Greek Cypriots is that, alas, the majority (I calculate them to be 60 to 70%) is indeed hard-line and most of them are relatively well-off, so they have difficulty contemplating power-sharing with the poorer Turkish-Cypriots.

Τhe Prespes Agreement, singed this summer between Greece and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia has caused political upheaval in both countries. How do you evaluate the agreement?

The best known Greek expert on the Macedonian question, who is now in his mid-80s, is Evangelos Kofos. He served as an expert at the ministry of Foreign Affairs for three decades. As the official historian of the Greek state on the issue of Macedonia he presented the Greek point of view, but in a sophisticated and subtle manner. In 1992 when the issue blew up under Antonis Samaras as Foreign minister, Kofos was sidelined. They didn´t want to listen to his advice, because his basic concept was that Macedonia was a geographical region, which in 1913 was divided among three states: Bulgaria, Greece and the Yugoslavia. Thus Macedonia is a geographical term that applies to all three of them; no country should monopolize the term Macedonia, so you need to add an adjective to be specific about which part of the region you refer to.

What I defend in my book on the Macedonian Question and in the relevant chapter in the book on the national issues, is a self-standing and viable agreement, ideally one that is either win-win or of the split-the-difference kind. Usually what happens when a deal is clinched is that the two parties tend to see it as of split the differences kind, that is of having more or less equal gains and losses; the win-win perspective comes later, once the fruits of the resolution become more apparent, with good relations, economic exchanges, contacts and so on. My assessment of the Prespes Agreement is that it tends to be lop-sided in favour of Greece. Of course according to the Greek nationalists, this is not the case, because ‘we’ should not have given them the two things in particular: the ‘Macedonian language’ and the ‘Macedonian citizenship’, not least because it could imply also ethnicity or lapse into ethnicity or nationhood.

Now as for the Macedonian language, it has been recognized as such by the United Nations since the days of Konstantinos Karamanlis’ premiership. During a United Nations conference that took place in 1977, in Athens, the Macedonian language was mentioned as being a distinct Balkan Slav language by the Yugoslav representative and the Greek representative at the conference raised no objections. So we are not giving them anything on that score, it is theirs since 1977. As regards citizenship, they have accepted to change their name to North Macedonia, to change their name and their collective national identity which they have since 1944, for 75 whole years – we are talking about three generations who have known their country as Macedonia and themselves as Macedonians. This a great sacrifice for them. Hence they had to be given something in return, and that is at least their citizenship as Macedonian. Furthermore, they have to change a number of articles in their Constitution (something very unusual by the standards of international diplomacy, such a thing happens following a defeat in a war), as well as changes in the schoolbooks and so on. The burden is on their side; they have to do all this, and Greece got off scot-free regarding a couple of things that, to my mind, should have been included in the Prespes Agreement for it to have been better balanced and win-win for both parties.

For example, for some reason, I cannot fathom why, the negotiators on the other side, did not press the Greeks to include something about the famous ‘phantom minority’, as put by a Konstantinos Mitsotakis and other Greek politicians across the political spectrum. The members of this ‘phantom minority’ are Greek citizens, who reside in the north of Greece, in Florina, Pella and Kastoria. They are the majority in some regions and they happen to speak another language; Slav-Macedonian or perhaps a Bulgarian dialect is their mother tongue. They exist, they are there; you can go and see them and speak to them (they are bilingual). I reckon that roughly half of them regard themselves by now as Greek, because Greek identity, even today, like in the 19th century is more attractive than other Balkan identities -especially those of new and insecure national identities. They say that they are of Slavic origin but they are now Greeks, they have chosen to be Greek. However, the other half of these people, regard themselves as something different and remember how their ancestors were treated under the Metaxas dictatorship and in the 1950s. Half of them fled Greece at the end of the civil war; note that the Slavo-Macedonians were the majority of ELAS (Greek People’s Liberation Army) in the second part of the 1940s, during the Greek Civil War. Their numbers now in northern Greece are very limited. So there is no threat whatsoever to the territorial integrity of Greece, a powerful country by Balkan standards, with a strong army, navy and air-force. How can it possibly be threatened by a country that barely has an army? I finish my book on the Macedonian Question by saying that if the Prespes Agreement is to be self-standing, duly implemented and so on, something should have been added with regard to that minority and I suggest the use of the term, not minority which is a loaded term in Greece, but ‘ethnic group’ or a ‘linguistic group’ for those of them that regard themselves as ethnically non-Greek, on the basis of the fundamental human right principle of self-definition.

Because a number of people in Greece are going to be furious with I have just said and written in my book, I added a footnote, in the last page of my book on the Macedonian Question: I point out that this was exactly my proposal to foreign minister Antonis Samaras almost 30 years ago, in February 1991 in a top secret document (which I called a non-non paper) which I sent him and which he did read. So if I may so, if I held that view then as a functionary of the Greek foreign ministry, I may be allowed to hold the same view now as an academic with far greater freedom of speech.

What role can Greece play in its region (South East Europe, Eastern Mediterranean), especially in view of current geopolitical developments?

To the extent that it resolves its outstanding national issues -except with Turkey, as I said this is a special case due to the Erdoğan factor- but, if it resolves the issues with other countries like Albania and North Macedonia, Greece can play a very constructive role in the region. But it should leave aside its arrogance. Greeks, politicians and citizens alike need to understand that all the other countries, or most of them (except some ‘rogue states’ or ‘criminal states’) are equally important, and should be equally respected. This goes back to the theory of nationalism in the 19th century. Then there were two schools of thought on the matter within the spirit of nationalism: one was Fitchte’s, who advocated a ‘favourite nation’, in the sense that ‘my nation’ is better than other nations, it has a greater contribution to world civilization; and the other was the approach of Mazzini and partly Herder before him, that ‘all nations are important’, and worthy of respect qua nations, there can be no hierarchy among them. The moment you have a hierarchy, you have ethnocentrism and you make a mess of it, especially with your neighbours across the border; because other nations are obviously not going to agree with you when they realize that you regard yourself superior to them. Another problem with the Greeks, apart from believing they are the direct descendants of the ancient Greeks, who are unsurpassable as the cradle of European civilization, is that at the same time, they compare themselves with the great civilizations of Europe (from the Renaissance until today), the French, the British, the Germans, the Italians, the Russians. You cannot compare with them!

If we Greeks compared ourselves with smaller nations in our own league as it were, such as Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Romania, Serbia or Bulgaria, we would discover that we have done very well in modern times. For example, some important composers of modern classical music are Greeks, such as Nikos Skalkottas, Anestis Logothetis, Yiannis Papaioannou, Michael Adamis, Jani Christou and Iannis Xenakis. Modern Greece has had a very worthwhile cultural and scientific contribution to the modern world, despite its relatively small population. So there is no need for an insecure national identity that breads haughtiness and arrogance towards one’s neighbours.

Read more via Greek News Agenda and Rethinking Greece:

*Interview by Ioulia Livaditi and Nikolas Nenedakis