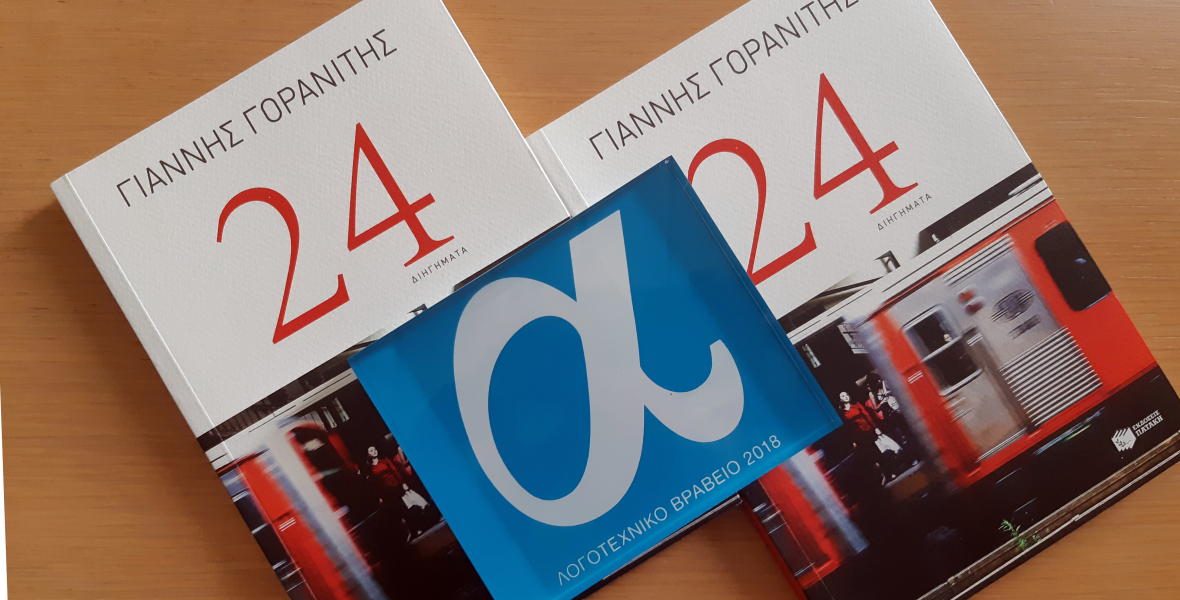

Yannis Goranitis is a fiction & non-fiction storyteller. He was born in Athens, where he lives and works as a journalist and ghostwriter for Viografi.es | Boutique Publishing House, that he co-founded in 2015. For his first book, a short story collection entitled 24 (Patakis, 2017) he was awarded with the ‘Anagnostis’ literary magazine “Best newcomer prose writer” and was shortlisted for the “Best newcomer writer” award of Hellenic’s Authors Society. Various short stories have been awarded in literary contests and published in short stories collections, literary magazines and websites.

John Goranitis spoke to Reading Greece* about 24, “a modular collection of 24 short stories, which are numbered according to the respective electric railway stations”. He explains that “all stories take place, originate or are inspired by its passengers, while all incidents take place in wagons or platforms”, and adds that “the convenient literary condition 24 was based upon is that the same train moves throughout the city, thus offering a single narrative context that includes heterogeneous characters and unpredictable situations”.

Asked about the main challenges that new writers face in order to have their work published, he comments that “the Greek book market has been hit hard during the crisis, which is the primary reason publishers appear quite reluctant to publish works by newcomers”. He concludes that “writers who make ends meet solely by writing fiction are no more than a dozen”, and “it’s not just that the Greek book market is small (and continues to shrink), but that there is almost no interest in translations to other languages”. “The situation could possible be reversed in case there were applied the necessary policies; I don’t mean sinecures and political favors but a balanced policy that would not only support the book market but may also boost readership”.

Your first short story collection 24 received rave reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

The book constitutes a modular collection of 24 short stories, which are numbered according to the respective electric railway stations (from #1 Kifissia to #24 Piraeus). All stories take place, originate or are inspired by its passengers, while all incidents take place in wagons or platforms. I call the collection ‘modular’ because many of the short stories continue at next stations, while some of the characters pop in and out of the stories of others. Several book critics noted that the book is not a short stories collection but rather a novel due to the dense interconnecting threads. They are probably right and it’s true that I wrote the book within a single framework; yet I prefer to fulfill the promises I give to readers.

Most of the stories take place within the Athenian urban landscape, which, in your words, constitutes “an ideal reflection of modern life, in which the characters try to integrate and survive”. What led you to choose railway stations as the protagonist of the book? Would you say that Athens is a literary city?

The convenient literary condition 24 was based upon is that the same train moves throughout the city, thus offering a single narrative context that includes heterogeneous characters and unpredictable situations. Another thing is that the day the short stories take place coincides with a taxi drivers’ strike and a long-lasting strike of petrol stations. That’s why people of different economic and social backgrounds and origins use the train; and the same goes for passengers who wouldn’t normally take the train: from a doctor returning home after being all night on duty to the partner of a patient treated by that doctor, from a drug addict to a Troika executive, from a claustrophobic writer to a naughty boy that escapes his mother’s attention and is lost in the wagons.

It has been argued that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

Indeed there is a strong tradition of short stories in Greece, with the work of Alexandros Papadiamantis as its obvious starting point, while major short story collections and individual short stories were published throughout the 20th century. Despite the commercial downturn in the Greek book market overall and the anti-commercial nature of short stories, remarkable mobility has been recorded in recent years, with many young and older writers opting for short form. On the other hand, contemporary Greek literature has quite important novels to display, as well as many distinct attempts in longer forms. I reckon that the distinction between literary genres is, after all, obsolete. What actually matters is the dynamics of the story, the narrative means and the distinctive style. Which mold will be used to fit all these, is, as far as I am concerned, of minor importance.

“What differentiates journalism from literary writing is neither creativity nor form or style. It’s actually the special weigh that each carries after reading”. Tell us more.

The differences between journalistic and literary writing are definitely numerous and unquestionable. Yet, there are also common elements, primarily language. This does in no way mean that the two fields are identical. Simplifying that, I’d say that words for writers and journalists are like color for artists and wall painters. That’s why I lay emphasis on the ‘imprint’, the feeling a reader gets when reading a book. And, all the more, the writer himself. I definitely don’t want to underestimate the work I have been doing for the last twenty five years, neither to be accused of unfair generalizations, but I still have to note the following: of course there are innumerable well-written, thoughtful and creative journalistic texts, as there are innumerable badly written literary texts.

Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their workpublished? What role do the social media play in the promotion of new literary voices?

The Greek book market has been hard hit during the crisis. This is the primary reason why publishers appear quite reluctant to publish works by newcomers. Thus, there are numerous new remarkable voices that go unnoticed and many books that never leave the drawers, while many writers are forced towards self-publishing, covering publishing expenses themselves. Personally, I was fortunate enough to have my book published by a major publishing house, which has both the network and the experience required to support a new book by a virtually unknown writer.

As for the role of social media, I reckon that they exert a positive influence vis-a-vis new publications, notification of events, contests etc, while they enable introverted authors like myself to be promoted. Yet, on the long-term, their influence may prove quite negative given that artists are exposed, sometimes irreparably, while readers may feel quite annoyed when their timelines are literally inundated with publications, comments, photos, reviews etc of books written by hundreds of authors and publishers. Not to mention the long hours in front of a screen. So balance is the happy medium.

For the majority of Greek writers, writing is not a main profession but rather a leisure time activity. Would you agree that in a country stricken by the crisis, earning a living through writing is the exception rather than the rule? Could things be otherwise?

Of course there are an exception to the rule. Writers who make ends meet solely by writing fiction are no more than a dozen, and this will unlikely change in the years to come. It’s not just that the Greek book market is small (and continues to shrink), but that there is almost no interest in translations to other languages. The situation could possible be reversed in case there were applied the necessary policies; I don’t mean sinecures and political favors but a balanced policy that would not only support the book market but may also boost readership.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE