“We are all Greeks. Our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts have their root in Greece”

― Percy Bysshe Shelley

The word Philhellenism derives from the Greek word philos (friend) and Hellenism (the study and appreciation of Greek language, culture and civilization). Hellenism was an intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th century, that flourished mainly in Germany and England and expressed itself through poetry, prose, sculpture and architecture. Philhellenes were inspired by the Hellenists’ idealized portrait of Greece. They associated ancient Greeks with the ideals of freedom and democracy, and their vision was to liberate Greece from the Ottoman Empire. The movement should also be seen as an organic part of the socio-historical realities in Europe several decades before the eruption of the Greek War of Independence.

Dr Pallikidis, professor at the University of Ioannina, in his essay about Philhellenism, explains that the foremost intellectual constituents of this historical era in the West were:

• Liberalism. Despite Napoleon’s defeat in 1815 and

the consolidation of absolute monarchy in European states, the democratic principles and the liberal ideals of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution continued to touch the people of Europe and beyond.

• Neoclassicism and Archeological Tourism. Already by mid- 18th century, the publication of works by J. Winkelmann and G. E.

Lessing influenced the intellectual world in Europe, seeking a model for the organization of European society among the values and ideals of ancient Greeks. Many travelers, like James Stuart, Nicholas Revett, William Martin Leake and others visited Greece in order to admire or artistically depict Greek ancient monuments. During their journey, they also became acquainted with the hardship of modern Greeks living under the Ottoman yoke.

The Massacre at Chios by Eugène Delacroix (detail)

The Massacre at Chios by Eugène Delacroix (detail)

• Romanticism. The Romantic Movement developed in Europe on

on the eve of the Greek Revolution. It was mainly expressed in

literature and painting, and its structural features included the expression of strong feelings, unbridled imagination, unrestricted freedom,

the denial of social conventions, heroic splendour and the return to the ancient cradle of civilization.

When the Greek War of Independence broke out, Liberals and Romantics from around Europe raised their voices in support of the Greek Revolution.

Although the governments of Europe were in the beginning unwilling to support the Greek revolution, philhellenes from all over the world began coordinating their actions to provide assistance to the struggling Greeks.

American and British Philhellenes

A very strong movement of Philhellenism flourished in the USA and Great Britain, and it may be safe to say that the outcome of the War of Independence would’ve been different without the support of its followers. We will note here only some of the American and British Philhellenes who came and fought on the Greeks’ side during the war and/or sent money and supplies that saved the lives of thousands of Greeks.

The American Revolution in 1776 was inevitably an inspiration for the enslaved Greeks to fight for their liberation. When the Greek Revolution broke out in 1821, American philhellenes began a lobbying campaign in the United States for the support of Greece

On May 25th, 1821, Petros Mavromichalis, on behalf of the Messinian Congress, sent a letter to the then Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, which was published in American newspapers, asking for moral support.

Samuel Gridley Howe

Samuel Gridley Howe

On December 3rd, 1822, US president James Monroe in his annual address to Congress said: “A strong hope is entertained that the Greeks will recover their independence and assume their equal statue among the nations of the earth.”

Unfortunately, on December 2nd, 1823, President Monroe announced the “Monroe Doctrine”, which in essence excluded the United States from getting involved in European affairs.

Despite the government policy of neutrality many Americans gathered to support the Greek independence movement and established philhellenic societies throughout the United States.

- The first volunteer American to travel to Greece and join the Greek War of Independence was George Jarvis, a New Yorker, who went to Greece in 1822. He joined Kleftes (guerrilla fighters) and became known as “Kapetan Zervos”. Jarvis participated in many battles and was repeatedly wounded. He died of natural causes in Argos on August 11th, 1828. Jarvis became a model for other American volunteers.

- Samuel Gridley Howe, a Bostonian physician and abolitionist, after his graduation in 1824 came to Greece, enlisted in the Greek Army and for six years served as a soldier and chief surgeon. In 1827 he returned to the USA to raise funds and supplies for the suffering Greek people. He managed to raise about $60,000 which he spent on provisions, clothing, and the establishment of a relief depot for refugees near the island of Aegina. In 1866, during the Cretan Revolution, he returned to Greece with his wife Julia Ward Howe, to organize support for the new uprising of the Cretans against Ottoman tyranny and enslavement.

Left: Samuel Gridley Howe painted in the dress of a Greek soldier by John Elliott, Right: Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips

Left: Samuel Gridley Howe painted in the dress of a Greek soldier by John Elliott, Right: Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips

- Another American Philhellene was Jonathan P. Miller of Vermont, who arrived in Messolongi on November 26, 1824. During the next two years, he rose to the rank of Colonel in the Greek military and in Jarvis’s regiment. Miller quickly mastered the Greek language, adopted Greek dress and was fearless in battle. In December 1824, he participated in the proceedings of the convention in Anatolico, Aitolia (western Greece). Miller was in Messolongi during its siege and in a letter to Edward Everett dated May 3rd, 1826, he described the heroic “exodus”, the subsequent fall of Messolongi and the massacre of its population by the Ottomans

Captain Jonathan P. Miller returned to the United States in 1826 and through the efforts of the Greek Philhellenic Committee of New York, he was able to collect $17,500 worth of various relief supplies, which he took back to Greece onboard the ship “Chancellor”, on March 5th, 1827.

British Philhellenes

The uprising of the Greeks against Ottoman rule during the 1820s commanded a wide sympathy throughout the western world such as no government could ignore. As in most European countries, there was also in England a strong philhellenic movement that played a significant role in the liberation of Greece.

- In 1823 the London Philhellenic Committee (1823–1826) was established, to support the Greek case by raising funds and by raising a major loan to stabilize the fledgling Greek government. The committee was established by John Bowring and Edward Blaquiere. Its early members included the reformer Jeremy Bentham and Lord Byron.

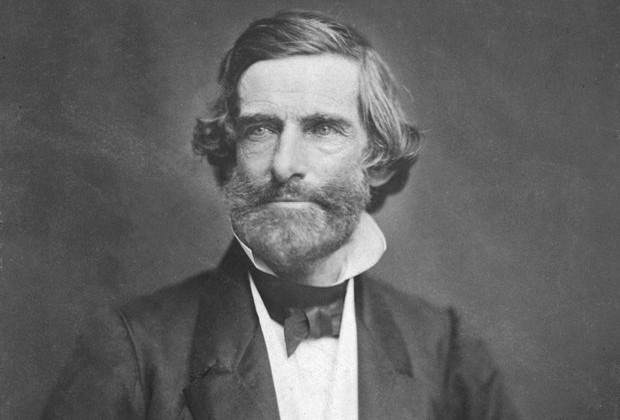

Lord Byron is considered the principal instigator and face of philhellenism. Born in 1788, George Gordon Byron became the leading figure of British Romanticism at the beginning of the 19th century.

At the age of 21, Byron entered the House of Lords, and the following year he began his long journey to the Mediterranean, where he wrote one of his most famous poems, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, a description of the travels and reflections of a young man, who looks for distraction in foreign lands. Byron was also a strong opponent of Elgin’s removal of the Parthenon marbles. His poem “The Curse of Minerva” is a severe attack against Lord Elgin and his taking away from Greece the Parthenon sculptures.

In April 1823, Byron agreed to act as agent of the London Committee, organized funds and supplies (including the provision of several ships) and in July 1823 he left Genoa for Cephalonia. He sent £4,000 of his own money to prepare the Greek fleet for sea service and then sailed for Messolonghi on December 29 to join Prince Alexandros Mavrokordatos, leader of the forces in western Greece. Byron made efforts to unite the various Greek factions and took personal command of a brigade of Souliot soldiers, reputedly the bravest of the Greeks. The great philhellene fell ill in February 1824 and died on April 19, 1824 in Messolonghi, at the age of 36. Byron’s death helped to create an even stronger European sympathy for the Greek cause.

Left: Frank Abney Hastings by Spyridon Prosalentis, Right: Sir Richard Church as General of the Greek Army, depicted with the Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer (unkwon painter)

Left: Frank Abney Hastings by Spyridon Prosalentis, Right: Sir Richard Church as General of the Greek Army, depicted with the Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer (unkwon painter)

Lord Byron became a national hero for Greeks and a symbol of pure patriotism. Dionysios Solomos – Greece’s national poet who wrote the National Anthem –composed a long ode in his memory. Byron’s poetry, along with Eugene Delacroix’s art, helped arouse European public opinion in favour of the Greek revolutionary cause to the point of no return, and led Western powers to intervene directly.

- George Finlay George Finlay was born in 1799 and spent most of his youth in Scotland. His idealism and his enthusiasm for liberal causes prompted Finlay’s first visit to Greece in 1823, where he joined Byron. He bought property near Athens and became actively involved in the development of the city, but his schemes for the improvement of the country met with little success. For many years, he acted as the special correspondent of the London Times.

His History of Greece, produced in segments between 1843 and 1861, did not at first receive the recognition it deserved, but it has since been given by scholars in all countries a place among works of enduring value, both for its literary style and the depth and insight of its historical views.

- Frank Abney Hastings (1794 –1828) was a British naval officer and Philhellene. He served in the British Navy from 1805 until 1819, fought at the Battle of Trafalgar and the Battle of New Orleans, and sailed for Greece on March 1822, where he joined the revolutionary forces and took part in Greek naval operations.In a memorandum to Byron, Hastings proposedthe use of steamers instead of sailing ships, and of direct fire with shells and hot shot as a more effective means of destroying the Turkish fleet, however lack of resources prevented the implementation of his plans.

Painting showing the Karteria (centre-right, with sails down and smoke issuing from funnel) in action at the Battle of Itea (1827) by Yiannis Poulakas

Painting showing the Karteria (centre-right, with sails down and smoke issuing from funnel) in action at the Battle of Itea (1827) by Yiannis Poulakas

- Hastings, in co-operation with General Richard Church (commander of the Greek forces in the last stages of the War of Independence), decided on an attack in western Greece, where the destruction of a small Turkish squadron at the Battle of Itea in the Gulf of Corinth (29 September 1827) provoked Ibrahim Pasha into aggressive movements which led to the destruction of his fleet by allied forces (Britain, France, and Russia) at the Battle of Navarino. The Greek squadron at the Battle of Itea was led by the flagship Karteria, the first steam-powered warship to be used in combat operations in history.

On 25 May 1828 he was wounded in an attempt to reclaim Messolonghi, and he died a few days later from his injuries in Zakynthos on 1 June. Greece held a national funeral in his honor and he was laid to rest beneath the arsenal of Poros, today a Hellenic Naval Academy, and his heart is preserved in the Anglican Church in Athens.

Marianna Varvariggou (Intro image: The Reception of Lord Byron at Messolonghi by Theodoros Vryzakis)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Rethinking Greece: Roderick Beaton on the study of Greece and modern Greek achievements; Rethinking Greece: Miltos Pechlivanos on Greek-German cultural exchanges and the need to re-conceptualize Modern Greece