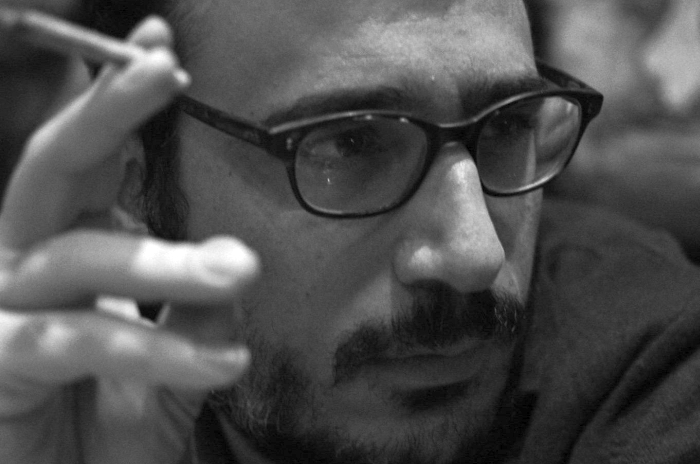

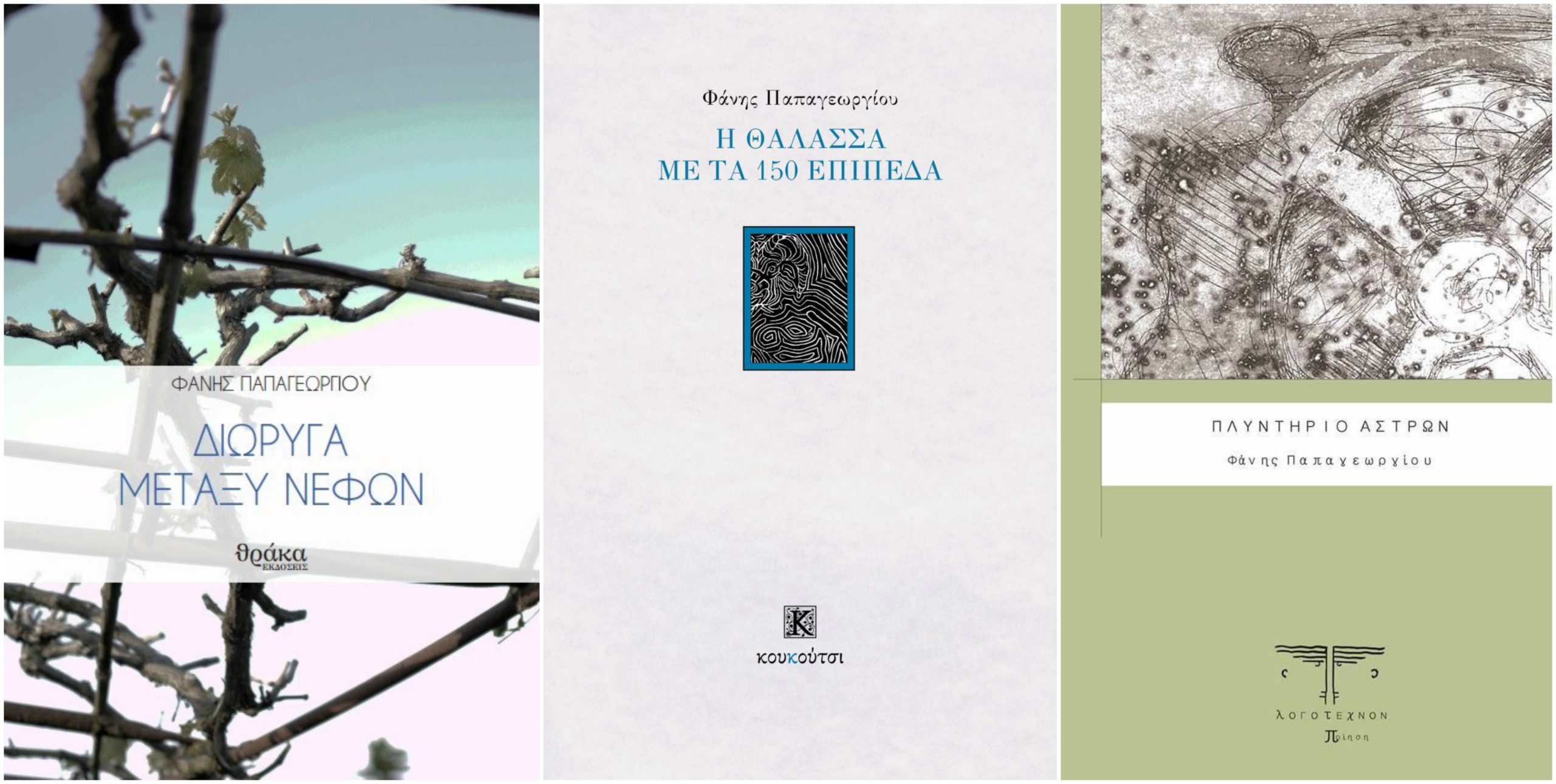

Fanis Papageorgiou was born in 1986 in Athens. He studied economics in bachelor and master’s degree and holds a PhD from the National Technical University of Athens in the field of political economy. He has written three books of poetry in Greek: Πλυντήριο άστρων [Laundry of Stars] (Logotechnon Editions, 2013), H θάλασσα με τα 150 επίπεδα [The sea with the 150 levels] (Κοukoutsi Editions, 2015) and Διώρυγα μεταξύ νεφών [Canal between clouds] (Τhraca Books, 2018). His first book was shortlisted for the newcomer poet award of the Hellenic Authors’ Society. His poems have been translated in English and Spanish. He is currently working as a lecturer at the National Technical University of Athens.

Fanis Papageorgiou spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest book Canal between clouds, in which he “attempted for ‘simplicity’ both in terms of ideas and form”, as well as on the main themes his poetry delves into, that is “how we live, who we are, how the world is, which are the universal values and so on, in order to ‘turn the world upside down’”.

Asked about the meeting point between poetry and political economy, he explains that “poetry, fighting against the dominant discourse of power, moves in parallel with political economy”, and concludes that “by using new ways of expression while staying vigilant against the possibility of dominant discourse prevailing anew, we can put poetry at the forefront of questioning the existing and building a ‘new’ man, who will unmediatedly converse with his needs and the others, so that poetry coupled with political practices turns the world upside down”.

Your latest poetry collection Canal between clouds was recently published by Thraca. Tell us a few things about the book.

It’s always difficult to talk about your works. What I can say for sure is that the book attempted for ‘simplicity’ both in terms of ideas and form. It tried to be simple without becoming simplistic; I hope it worked this way. It is, after all, the product of a socio-economic conjuncture during which things seem to settle, without, of course, being fully solidified.

In her review of The sea with the 150 levels, Maria Koulouri characterizes your poetry as “a madness pulp”, “a desperate attempt to exist, since madness is a way out, one last effort of being, a complaint against legitimacy and an urgent need for change”. Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon?

Maria Koulouri’s comment is quite insightful in that it bridges the artistic subject with the political one, madness with existence. Against the attributes of dominant discourse, individualism, economic rationality, discipline, it’s sometimes madness, artistic creation or political discourse that come to meet each other. In other words, political discourse and artistic creation should converge with utopia, with all the things that exist outside this world and its values. They should talk about things in a way that has never been used before.

This transcendent course may look to some as a void of meaning voluntarism at best, or as madness in the worst. This course towards things that “don’t exist” may be found in Gorgia’s “non-being”, that is things that even if they existed, couldn’t be perceived, known or understood, nor would someone name or transmit them in linguistic terms (ca. 485–380 BC; see also Andersen 2008; Reinertsen 2015). This course towards meeting all those things that have not been said comprises both discourse movements and practices.

For Sol Funaroff, an artist’s role is to transform himself from the distant recorder of individual events to the person who participates in the creation of new values and a new world, to the poet who proudly gives voice to the new experience (Hickman 2015). Along similar lines, Bezzel (1970, p. 35) explains that “a revolutionary writer is not the one who semantically devises poetic proposals that refer and aim to highlight the necessity of revolution but rather the one who uses poetic means to render poetry a model of revolution”. Therefore, my themes delve into how we live, who we are, how the world is, which are the universal values and so on, in order to turn “the world upside down”.

How are the strong surrealistic influences that characterize your poetry reflected upon your poetic language? What purpose does language serve in your writings?

This is quite a difficult question to answer! At times I have caught myself making up words by following their sound or their origins, while at others I insisted on literal meanings. Metaphors and similes certainly facilitate metonymies about the world and render surrealistic references more concrete. As for the importance and aim of language, it may sound commonplace but poetry itself is a linguistic process, albeit not an absolutely ‘rational’ one. Thus, ontologically, there can be no poetry without language. It’s one of those experiences that, unless mediated in language, cannot be considered experiences.

“Poetry and political economy converge in that they both fight for the re-invention of society”. Could you elaborate on that?

Getting back to the second question, I consider that poetry, fighting against the dominant discourse of power, moves in parallel with political economy, at least the way I perceive the word while working in the respective field, that is as a philosophical narrative, which refutes the instrumental, economistic, individualistic, disciplinary discourse of the economic science. In other words, philosophy and poetry both fight against the same thing, perhaps with different tools.

The re-invention of the world is the crucial issue here. It is clear, I think, that the new world will not emerge from nowhere, but will form through the non-acceptance of the existing one, on the fringes of such refusal. Of course, this cannot be achieved automatically but through collective imagination, whether it occurs in poetry, science or in everyday life. Breakthroughs and discontinuities often cut into the rails of continuity. Yet, it’s not enough to just refuse; we have to envisage what comes next, what is ‘non-being yet’. Refusal may be a step towards emancipation but not an end in itself.

I personally reckon that the crucial point in this fight refers to the concept of hegemony, that is to make a puzzle whose pieces will comprise all those aspects that oppose the dominant discourse, to make a creative collage of all the things that we currently consider crazy, voluntaristic or unthinkable. To focus on how we want to live.

Vassilis Lambropoulos notes that “of all the arts, poetry has been identified as the most representative of the current national crisis. It constitutes the major cultural domain where the Greek emergency and/or exception are being negotiated”. What is the relationship of poetry to the world it inhabits?

Vasillis was among the first to discuss such issues and has been prolific in his writings. The crisis condenses and confirms the spatial, generational and temporal similarities, thus leading to some kind of intersubjectivity, that is common notions and representations, or concluding that social relations “bear more truth that the subjects they connect” (Bourdieu, 2007). Yet, I should mention that it is necessary, albeit difficult, to fully understand this dialectical movement in which poetry reflects the evolution of the world in which it is born, while, it can at anytime, and through hegemony, define “language”, though not so successfully nowadays.

After all, for Marcuse, art is a phenomenon deeply rooted in society, while an artistic work forms part of a social entirety (Marcuse 1973, p. 108). In addition, Burger considers that every individual work is conceived and intertwined to a social reality, to which it owes its creation as part of a dialectical relationship, while for Calas, the social, historical and moral dimensions of being inevitably leave their mark on art. Finally, for Dilthey, “we don’t study history, we are history”. In other words, the past and present life experiences are connected through the current of history of which we are all part (Zimmermann 2015, p. 29). The crucial issue, as I already mentioned, is to compose an hegemonic discourse for the world, a discourse which, in its abstraction, will allow and call each one of us to take a stand vis-à-vis the questions of life; a discourse which, in its specialization, will allow and ask for the deconstruction of the dominant discourse, while being pleasant and emotionally motivating. After all, a discourse which will be unmediated by the values of today’s reality.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares to mention just a few. How is this trend to be explained?Could poetry offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

Massiveness is sine qua non for hegemony. Massiveness, however, comprises ontologically deeper levels vis-a-vis the dominance of power’s discourse. I reckon that the current conjecture demands that we be simple without becoming simplistic. To pose questions but also to come up with answers. By using new ways of expression while staying vigilant against the possibility of dominant discourse prevailing anew, we can put poetry at the forefront of questioning the existing and building a ‘new’ man, who will unmediatedly converse with his needs and the others, so that poetry coupled with political practices turns the world upside down.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE