Kostis Georgiou is an internationally acclaimed sculptor and painter, who lives and works in Athens. He has studied at the Athens School of Fine Arts under Dimitris Mytaras and Dimosthenis Kokkinidis, and at Royal College of Fine Arts in London under Peter de Francia. Georgiou has over 90 solo exhibitions and almost 100 group exhibitions to his credit, in Greece and abroad; he has won awards at international events, while several of his works have been chosen for permanent display in publics places, from the Athens Riviera to Suzhou (China), Brussels and France.

In late 2017, Georgiou found himself at the centre of a public controversy over the installation of his sculpture Phylax in a public space near the coast of Palaio Faliro, as there were claims that the bright red sculpture portraying a human-like figure spreading its wings looked sinister or even diabolical. The mayor, who made the commission, supported by a sponsor, defended the creator’s artistic choice. Vandalism resulted in the statue’s toppling by a small group of unidentified perpetrators in January 2018, causing a general outcry.

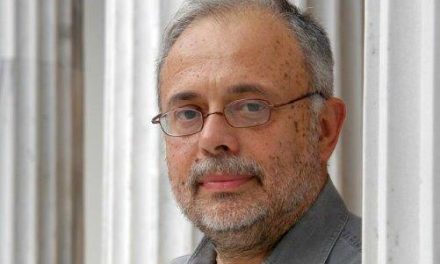

Left: The poster for “Enigma” exhibition Right: Praxis

Left: The poster for “Enigma” exhibition Right: Praxis

The artist’s latest project is the exhibition “Enigma”, which will be hosted at Teloglion Foundation in Thessaloniki. The display will take place at Teloglion’s hall and patio. “Enigma” will open on 10 May and will run until 9 June. It will then move to the Sismanoglio Mansion in Istanbul on 3 October, under the auspices of the Greek Consulate in Istanbul. Later in 2019, the exhibition will also be presented in Rome.

“Enigma” features about 100 of Georgiou’s paintings and 30 sculptures, including both older works as well as several new creations, including Praxis, a 4-meter tall monumental sculpture, which will be permanently donated to the foundation. The exhibition also features the video-art piece Aenaon, based on the 3d animation short film Violent Equation, by animator Antonis Doussias, inspired by the PHYLAX incident and selected at the 2019 Annecy Festival.

On the occasion of his exhibition, Kostis Georgiou spoke to Greek News Agenda* about his approach on the purpose of art and creation, his view on the connection between physical and mental labour and the influences that defined him.

Rhapsody of the Present

Rhapsody of the Present

In your essay, featured in the exhibition catalogue, you write that an artist’s work entails “hard back-breaking physical labour, exhaustion both physical and mental” and that the result shouldn’t be independent of the action, that true investigation exists when “action, concept, […] innovation coexist and constitute a system of values that is inextricably interwoven”. So you feel that physical involvement with the work of art…

…is of critical importance. In recent years we see a trend towards convenience, towards a type of conceptual art which, essentially tries to separate the action from the result; and that’s choosing the easy path. I don’t mean to say that we should reject conceptual art; on the contrary, any art form that has something to say and produces a work of art through an investigative process is welcome, no matter how strange, extreme or unconventional, it serves a purpose and has its merit. I do not denounce conceptual art, or any form of art, regardless of its features. It’s just that art often serves as a cover for the sly and the dubious who have failed elsewhere and want to play at something they are not; in other words, an easy solution. I don’t even condemn that, so long as they don’t try and deceive us. But there is a trend also evident in art capitals like Paris, London, or oversees, supporting a “light” form of art, cartoonish, akin to tracing. Sometimes there’s a sense to it, at times it’s just a funny picture.

As there are cases of, sometimes famous, artists who admit that their involvement is limited to having an idea, and then picking up the phone and describing what they want to specialised craftsmen, who take it up from there. This has often perplexed audiences, who can’t deny that the original concept does have its own merit, but still…

Yes, the concept has value of its own, but you see, the creator himself doesn’t get to have a hands-on involvement in the making process. And the thing is, an initial concept may have a specific form however, with time, during and as part of the creative process, it may take different forms, a different direction, one that is much more significant than the original concept. When taking part in the process, you are in direct contact with the resulting work, with its vibrations, which may lead you to greater things compared to your original intentions. Placing an order doesn’t give you this opportunity, as it doesn’t give you the satisfaction of making something yourself.

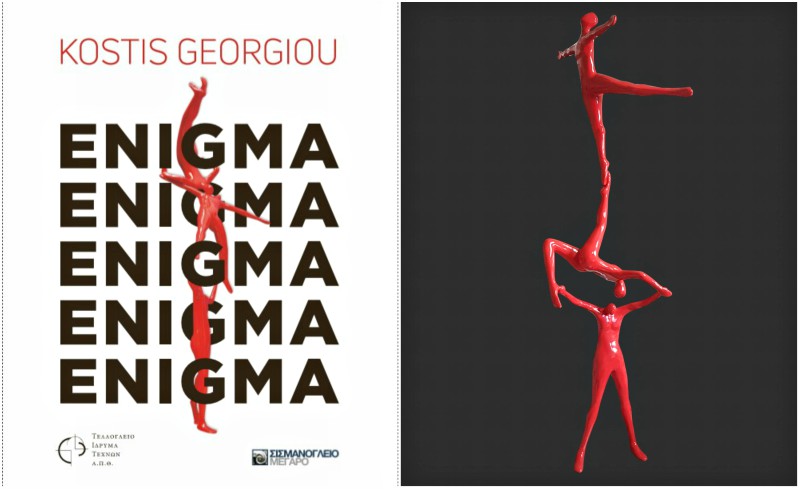

Left: Kostis Georgiou Right: Polymnia, part of the 9 muses series which will be presented for the first time

Left: Kostis Georgiou Right: Polymnia, part of the 9 muses series which will be presented for the first time

So ideas have merit, but many people can have an idea. I feel that there is something in art that you have to “quarry” for. It’s not easy, it takes hard work. At least in my case and for as long as I have been in this field, since I was 14 years old and up until now, I’ve been working non-stop. Not because I’m a workaholic but because I respect this field and I understand that this way I discover new things, which is the creator’s objective. You discover more about yourself, and we are always connected to our environment and the universe, so your personal truths, if they have real substance, will also resonate with those of other people. The purpose of art is this bridge it creates.

Art is otherwise reduced to a funny cartoon as it often happens now. And when art has no real content beneath its surface it loses its purpose, which is to educate the audience, give it food for thought. A cute and funny image of a cartoon character is something you can put on your wall, it doesn’t do much, and it is decorative without any true content. Of course, this type of art is promoted by the art system because it’s easy to make, even easier to sell and it can be done by many people without need for special skills; thus you can choose someone to do it and easily thrust them into stardom.

Left: Legatus Right: Taurus

Left: Legatus Right: Taurus

So you say physical labour is directly connected with mental labour, this process, as you write, by which the artist rejects “all that is useless and without substance” in order to get the final result. It’s safe to assume you don’t accept the notion of a “god-sent” idea that the artist receives as a vessel in its final and perfect form, but instead as something the artist has to put effort in.

Definitely. The ideas come to you, of course. This is where art is grounded, and we would be sterile without ideas, thus they have a decisive role. But this is where someone’s skill and creativity is put to test. Because anyone can have an idea, but it’s all about how you will convey this concept, adjusted through your personal knowledge, your own philosophy. The artist is not a maker of beautiful images, he is someone who renegotiates, in a way philosophises on life; otherwise, one is just a producer of hollow images. This is not the purpose of art, it may be a hobby, which is fine, but if we’re talking about substance in art, about the actual creative part, then we’re talking about a lot of effort, hard work, in unhealthy environments (turpentine, arc welding, etc.).

One might ask, why spend your life in an environment that could kill you? If I could do differently, I would. I cannot. I feel that this is my calling. I deeply love what I do, with the good and bad. Things are not easy and simple, and until you get your result you can make mistakes, you go through a lot of stages. When you put your knowledge, your work, your thought into a work of art, the resulting object has its own vibrations. These vibrations are what the viewer perceives, especially someone who tries to discover more through art. There are many types of viewers, and each has his place. To prevent any misunderstandings, it’s not necessary to have special knowledge in order to enjoy a work of art, because you can perceive and understand it with the eyes of the soul. A sensitive person can fully understand a work of art, as much, or more, than an expert.

Still from Antonis Doussias’ Violent Equation

Still from Antonis Doussias’ Violent Equation

You accept every viewer’s reception of the work of art as valid.

Of course.

But if you think of an ideal viewer, would you rather instigate them to think, to ask questions and try to solve the enigma, or rather feel, surrender, without trying to analyse?

As I said before, everyone is welcome. Each one has his own reason, his own substance, and is a member of the same “gang”. I mean anyone could make any projection on the work of art, as long as they don’t vandalise it. They can criticise it, they can praise it, they can ponder, or they can appreciate it solely as an image, a decoration. Anything goes. This is art’s purpose, to provide a zone of unlimited paths. If a work of art has limited scope and everything is predetermined, you restrict the viewers into perceiving the work in one particular way. There is this school of thought, where the creator favours absolutes, asks the viewer to see something specific and to acknowledge the artist’s competence.

To what extent are you concerned with beauty, with the aesthetic value of a work of art?

Look, I am an obsessive creator, and leave nothing to chance. A work of art is essentially a set of images and totally abstract elements coming from a person’s inner world. These are shapeless, odourless, massless. Like when you have a sort of dream and you want to describe to someone else the pleasant taste it has left in your mouth, but you can’t; this is the artist’s job. To take all these dreams and ghosts and images that make up his essence, pluck them from their haziness, and lay them down in the most comprehensive achievable way, so as to recreate the nearest possible condition to the one he experienced. The better you convey all these elements from within yourself, the better the viewer perceives what you have to tell. This is what art is all about, or else there are just some pretty images that catch the eye.

Left: Anatasis in Voula’s Central square (Attica) Right: Cosmicon at Vanke Midtown Mall (Suzhou, China)

Left: Anatasis in Voula’s Central square (Attica) Right: Cosmicon at Vanke Midtown Mall (Suzhou, China)

When such a concept is formed in you, is it always clear whether you will be able to render it through painting or sculpture?

No, it’s not. When you have the advantage of being active in two different branches you certainly have more possibilities. Painting and sculpture are inextricably linked, they’re communicating vessels. One borrows elements from the other. Painting describes the three dimensions; sculpture possesses them, but is limited by its materials. In a painting you can create various environments, in a sculpture you have to take functionality into account. Thus, each has its advantages.

Have you ever begun working on a painting only to decide that you should render your concept through a sculpture instead (or vice versa)?

Yes, this can happen too, a painting can eventually prove to be the sketch for a sculpture. It has quite often happened to me and left me amazed at how some things had been right there for me to see, and until then I hadn’t adapted them into sculptures. I was at the time probably too absorbed with fulfilling my aspirations in painting, so I missed what I was able to discern after a given time.

People often think of artists as loafers but, on the contrary, it’s someone ever vigilant. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve caught myself, in moments of relaxation or pressure, conceiving ideas which were of decisive importance for my work. Even when I’m putting myself to sleep, what I think about -instead of counting sheep- is how I’m going to build my next work.

Left: Galileo & Equus Right: Installation – Pompi A’

Left: Galileo & Equus Right: Installation – Pompi A’

You also create music.

Music falls into the same category. It’s not that I’m trying to pose as a universal genius or anything; it is just a need that has emerged in me, to approach art through a different medium. After all, sounds have a colour, just like colour has a sound. This is the reasoning behind my ventures in music.

Your music does share a common aesthetic with your visual art. Is it a way to express even more of yourself that you can’t convey through other means?

Definitely. Although I’m not a musician as I am self-taught, I love creating sound and try to do it through the perspective of visual arts. This too falls into the same range of actions and reactions. Music doesn’t come very easily to me; I need a period of cooling down, a time to allow ideas to settle, in order to be able to enter this world.

Is there something you feel you have taken away from studying under great masters like Dimitris Mytaras and Dimosthenis Kokkinidis?

To tell you the truth -with no disrespect to all my following teachers- everything I have gained as an artist and a painter was thanks to my first teacher, Panos Kousoutzidis, in Thessaloniki, where I grew up. He was a true giant, although mostly obscure to the public. He lived as a hermit; he was a philosopher and a magnificent artist. After all these years, and being now older than he was then, I still feel the same reverence towards him. He could have been one of the most renowned artists in the world if it wasn’t for his disdain for the lowly interactions that could have secured him recognition. I was lucky enough to meet him when I was around 14, along with another friend of mine, at one of his exhibitions, and to our great fortune he agreed to take us on as students, even though he was a recluse. He spoke four languages, knew Sanskrit and owned an outstanding library featuring all the great authors. He was the one to make us understand that art was more than images, something I understood better with time.

Left: Pope Right: Stalker D

Left: Pope Right: Stalker D

Keep in mind that, by the time I entered the School of Fine Arts I had already 10 solo exhibitions to my credit. I went to the school and worked, although I had my own workshop. There I could meet people who shared my interests, so it mostly functioned as a hub for ideas and for interacting with important artists and masters. Therefore it held an important role in my formation. The same is true for the Royal Imperial College. It was the environment and the interactions that mattered., as well as the fact that traveling, learning and analysing helps you overcome your insecurities, see things clearer, tell fake from genuine more easily. These are the better things that come with age and experience, as long as you have critical thinking – something often lacking in mass society.

To what extent would you say that your country has defined you? Whether we’re talking about the landscape, light and shapes, or about heritage, given the use of certain recurring mythological and historic themes in your art?

I don’t know if this can be clearly determined. As we said earlier, one’s environment plays a role; I would be exposed to completely different images if I was born somewhere else. I believe that sometimes your life can be determined by a random event. An opportunity or an adversity can open a new road. I’m not sure of every event which has shaped me as an artist. I believe one of the things that prompted me to this path was the influence of my older brother, who was into cinema, and I read his books on cinema theory and philosophy that I could barely understand as a young boy, mostly I got a sense of those things. But my interest in painting really became clear once I met my teacher, Kousoutzidis.

If I could give an explanation as to what defined me I would say it’s my sensitivity in my perception of the world. My eyes notice things others may not observe. Of course now this is a matter of habit, since this is the tool for my job.

Phylax in Palaio Faliro

Phylax in Palaio Faliro

What about Phylax? I understand it won’t be restored to its original location in Palaio Faliro.

I didn’t want Phylax to be returned there because I believe it would again be subject to similar attacks by this same group of people. It must be noted that this was a minority, albeit a very belligerent one, as is often the case with such minorities. This work of art has been subject to many insults. The first one was of a farcical nature; a group of people claimed it portrayed Satan and sprinkled it with holy water. But then there were the actually violent elements that pulled down the statue. The final insult came from the inaction when it came to ensuring its restoration. The Ministry of Culture had a tepid reaction, as did the Chamber of Fine Arts.

Through all this, I got a deeper understanding of the structure of Greek society and how toxic it can become, of who really supports freedom in art and who is narrow-minded. We must however say that most people were saddened by these events. The location where the statue was placed was completely neutral and humdrum. And now it has gone back to being just that. What’s worse, this situation deterred all those sponsors who had wished to finance the installation of more works of art in public spaces in the area. The Chamber of Fine Arts made matters worse by seeking to introduce a procedure of public tendering, which can’t work out since a sponsor usually wants to provide funding for a specific artist that he has in mind. So in a word, no, the statue will not be restored.

Diver in Ios island

Diver in Ios island

Has this experience made you more reluctant to take on commissions for public art works?

No, not at all; in fact one of my works was very recently installed on the port of Ios island, and in a few days another one will be placed in Varkiza. A year ago an artwork was installed in Alexandroupoli. This whole story didn’t cause me insecurity; after all, there are works of mine displayed in cities abroad. At the time, I was plied with questions and interview requests from every possible source, which got in the way of my work, so I decided to hang up the phone instead of giving in to these distractions for the sake of publicity. I think that withdrawing from all this attention and the public feud fueled by the media was the best choice.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Panos Charalambous on the 180 year history of Athens School of Fine Arts; Denys Zacharopoulos: A museum should function as an open window between the private and the public life of people; Alexandros Psychoulis on the idea of symbiotic bliss & the reality of working as a visual artist in Greece; Dimitris Mytaras at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Andros