Maurizio De Rosa was born in Milan in 1971. He translated into Italian some of the most important works of contemporary Greek literature such as the novels E con la luce del lupo ritornano by Zyranna Zateli (in Greek: Και με το φως του λύκου επανέρχονται), Addio Anatolia by Dido Sotiriou (in Greek: Ματωμένα χώματα), Libro Doppio by Dimitris Hatzis (in Greek: Διπλό βιβλίο), L’interrogatorio by Aris Alexandrou (in Greek: Το Κιβώτιο) and so on, as well as Konstantinos Kavafis’ selected works. He is a member of the Italian Association of Modern Greek Studies and the Hellenic Authors’ Society. In 2016 won the Hellenic National Award for Translation. He wrote Bella come i greci, a history of Greek literature from 1880 until 2015 (UniversItalia Publishing House, Rome 2015).

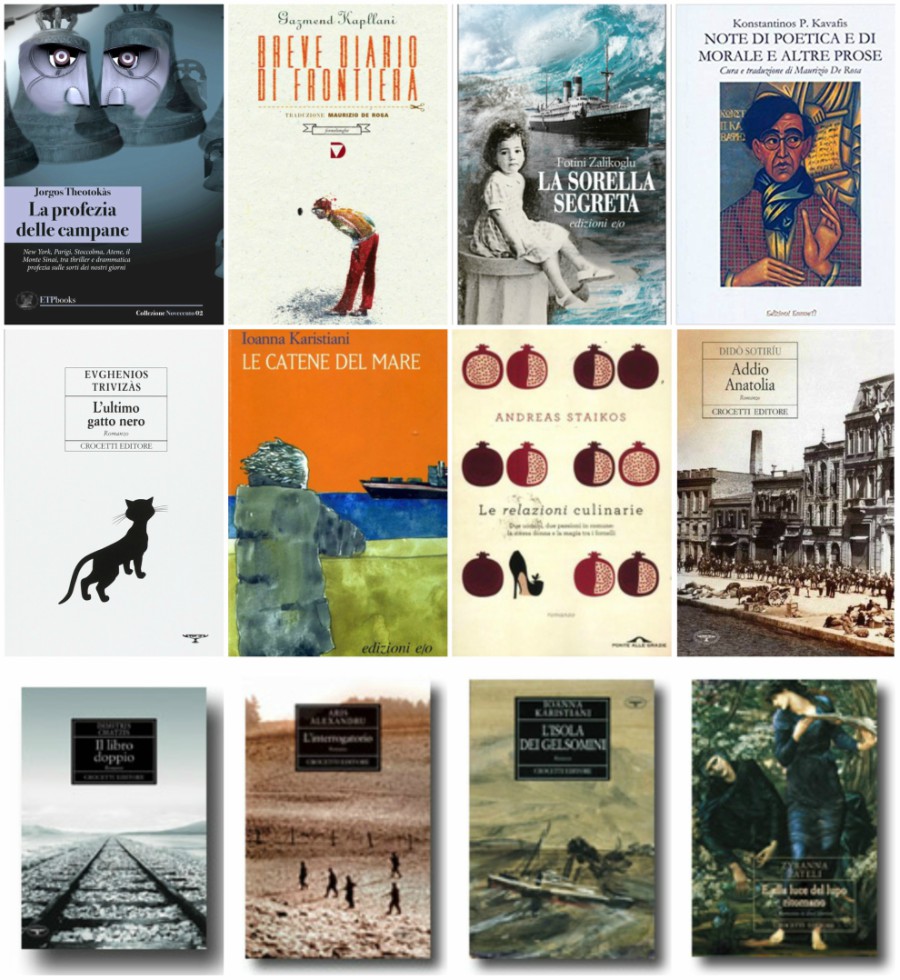

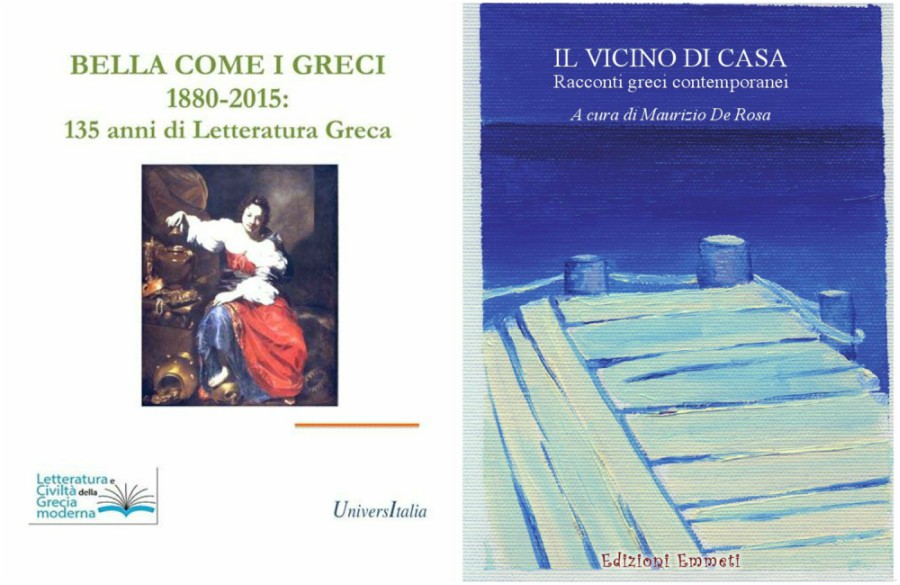

Selected works of his include: La profezia delle campane, by Yorgos Theotokas (Οι Καμπάνες), ETPBooks, Atene 2017, Breve diario di frontiera, by Gazmed Kapllani (Μικρό ημερολόγιο συνόρων), Del Vecchio, Roma 2015, La sorella segreta, by Foteini Zalikoglou (8 ώρες και 35 λεπτά), e/o, Roma 2014, Νote di poetica e di morale e altre prose, by Konstantinos Kavafis, EmmeTi, Milano 2013, Il vicino di casa. Antologia del racconto greco contemporaneo, an anthology of Modern Greek short stories by Maurizio De Rosa, EmmeTi, Milano 2011, Le catene del mare, by Ioanna Karistiani (Σουέλ), e/o, Roma 2008, L’ultimo gatto nero, by Evghenios Trivizàs (Η τελευταία μαύρη γάτα), Crocetti, Milano 2004, Le relazioni culinarie, by Andreas Stàikos (Οι επικίνδυνες μαγειρικές), Ponte alle Grazie, Milano 2002, L’isola dei gelsomini, by Ioanna Karistiani (Μικρά Αγγλία), Crocetti, Milano 2000.

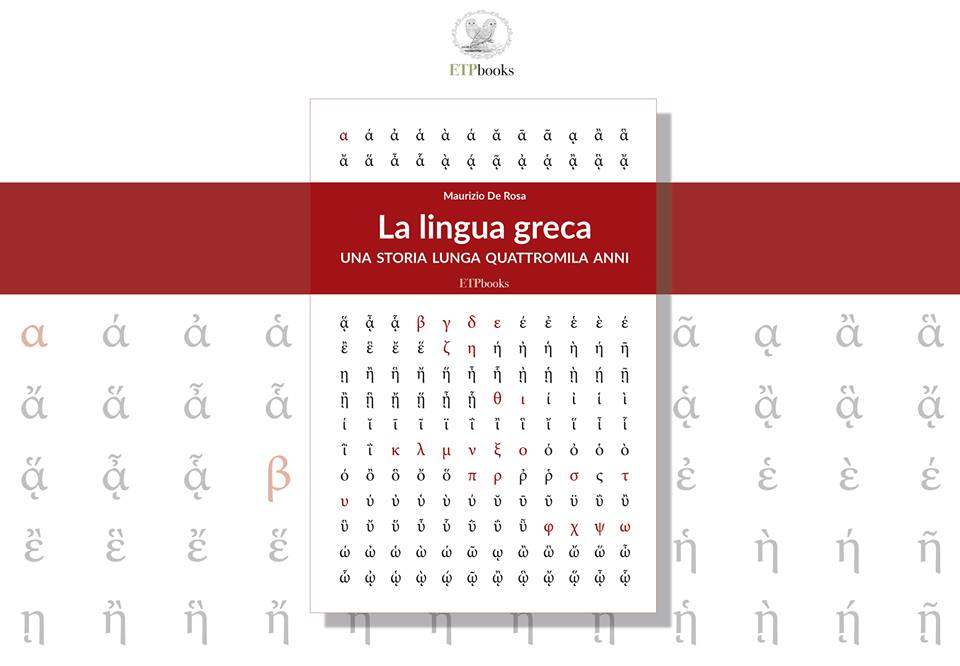

Maurizio De Rosa spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest book La lingua greca: una storia lunga quattromila anni, which tells “the history of the Greek language from the tablets written in the Linear B script to the present day, with a special emphasis on the dispute over language”. He comments that “translation constitutes a form of interpretation and acting, in the same way as an actor’s or a musician’s, and the translator is called to convince the reader that the original text was written in his/her language in the first place”, and adds that “translation becomes unethical when it is bad, when it is artistically invalid”. As for the prospects of Greek literature in Italy, he concludes that “what Greece actually needs is to set clear and realistic goals vis-à-vis the promotion of its literature abroad, as well as to find ways to implement them both consistently and continuously” so that Greek literature attains the position it deserves in the literary world.

La lingua greca: una storia lunga quattromila anni was recently published by ETPbooks. Tell us a few things about the book.

The book tells the history of the Greek language from the tablets written in the Linear B script to the present day, with a special emphasis on the dispute over language which beset the intellectual, social and political life of the Greek state for almost 150 years, while it constitutes and exciting narration. This dispute is also examined within the framework of the respective historical events in the long course of the Greek people so that the reader acquires an overall idea of the phenomenon called Hellenism. In Italy, no such book exists and my intention is to offer a concise and, hopefully, easy-to-understand handbook for all those involved in the Greek language – primarily high school and university students, old students of the Classical Lyceum, scholars, philhellenes, as well as every inquisitive reader.

What motivated you to turn to the Greek language and more specifically to the translation of Modern Greek literature?

In 1992 I was studying Greek and Latin Philology in Milan so I travelled to Greece for the first time in order to visit museums and archaeological sites. I was deeply moved by modern Greece, a mixture of continuity and disruption, of old and new, for which I was no way prepared at the University. What mainly fascinated me was the language, its modern form, which comprises the psyche of the Ancient Greece, while at the same time reflects on the entire historical course of the Greek people throughout the centuries. When I returned to Italy, I attended Modern Greek Language courses with the professor Amalia Kolonia and five years later, when I graduated, I came in touch with the publisher and Hellenist Nicola Crocetti, who at the time was about to start a modern Greek literature series titled Aristea. He asked me to translate the novel Και με το φως του λύκου επανέρχονται (E alla luce del lupo ritornano, At Twilight They Return) by Zyranna Zateli. More than 20 years have passed since then with nearly 60 translations.

“A good translation is “a translation that remains faithful to its nature in the same way as a good actor who deceives his audience with the naturalness of his acting”. Tell us more.

The dispute over translation starts in the era of Cicero and the Latins, whose literature begins with the translation of the Odyssey by the Greek Livius Andronicus. That’s the starting point of the debate on the artistic and literary essence of translation and mainly on the practice of translation – in this sense, translation is a form of acting, a term whose etymology relates to the Latin verb ‘ago’, which in Greek means ‘δρω’ (from which ‘drama’ derives). Thus translation constitutes a form of interpretation and acting, in the same way as an actor’s or a musician’s, and the translator is called to convince the reader that the original text was written in his/her language in the first place. To attain this, specific concessions should of course be made as in the theatre – in the case of translation, the reader concedes to follow a story in his/her language, although the story takes place in another context. For this to work in practice, the reader’s consent is not just necessary but of pivotal importance; it’s this consent that offers a translation its epistemic and artistic legitimacy.

It has been argued that when translating from “minor” language or literature, translators do sometimes hold remarkable power, including the power to produce what will in many cases become the only interpretation of a work of literature available in a given language. In this context, where does the role and the responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

Translation becomes unethical when it is bad, when it is artistically invalid. The ethics of a work of art (and translation is, with all its limitations and in a different context, a work of art) is its aesthetics, with consistency and the artistic result as its benchmarks. In this respect, the translator has a great responsibility. The filioque dispute, which triggered the schism between the Eastern and Western Christian churches, was due, apart from the lack of goodwill and good faith on the part of the protagonists, to an error in the translation from Greek to Latin and the Pope recently “corrected” the Italian translation of Our Father; yet it was the original translation which formed and defined consciences, worldviews, philosophies and even popular wisdom.

I have deliberately chosen the thorny field of the Christian religion, because it preaches that the Word was incarnated, it acquired a physical body, and became the “truth” for believers – yet this truth often varies according to the translations and the distinct character of each language. As to the issue of the only interpretation of a work of literature that you mention, unfortunately this is the price that the so-called ‘minor’ languages and literatures have to pay. In the case of Greek literature, Cavafy is the only poet to be translated again and again and in part Kazantzakis, Seferis, Ritsos and Elytis. On the other hand, Drifting Cities by Stratis Tsirkas, for instance, were never translated into Italian, with the exception of The Club (Il circolo) Let’s just make the first step.

What do you reckon is the profile of the Italian audience that reads Greek literature? And, in turn, what is that makes Italian literature appealing to Greek readers? Are the major similarities that exist between the two countries, as countries of the European South, reflected upon what readers in both countries opt for?

Whichever similarities that may exist between the two civilizations in no way constitute a guarantee that the respective literatures will be mutually recognized. Readers often opt for exoticism and the ‘other’, and in this respect, similarities turn into a burden. As for Greek literature readers in Italy, I would say there are two distinct categories. On the one hand, we have the ‘philhellenes’, people who are acquainted with or travel to Greece and yearn for a more substantial encounter with its civilization. On the other hand, we have those readers who choose Greek writers in the same way they opt for Americans, French, Scandinavians and Israelis. For instance, readers of, let’s say, Petros Markaris or Lena Manta, to mention two writers who have in recent years conquered the Italian audience, are not necessarily acquainted with Greece. In their case, there is a common psyche which also touches the hearts of Italians. I reckon that the same goes regarding the way Italian literature is perceived in Greece.

Given that the publishing landscape in Italy is also crisis-stricken, which are the prospects of Greek literature in Italy?

What Greece actually needs is to set clear and realistic goals vis-a-vis the promotion of its literature abroad, as well as to find ways to implement them both consistently and continuously. Greek literature is not the only ‘minor’ literature that seeks its vital space abroad. In Italy, where the reading audience is, after all, limited, Scandinavian literatures constitute a case in point, given that they are mainly promoted by a specialized publishing house, while the interest of major publishing houses is just sporadic. This is an example that should be taken into consideration in order to strengthen the relationship between Greek literature and a core of loyal and faithful readers.

Being fully aware of the difficulties and the real potential – what I call ‘realism’ – will help creators avoid frustration while it will contribute to the implementation of a more effective policy for the promotion of Greek literature. Currently in Italy even French literature is being translated to a relatively limited extent, while pressure is also exerted on the omnipotent “Anglo-Saxon” literature, which is regarded by default as “avant-garde”, “qualitative” and “interesting”, while it is promoted by an irresistible system which takes advantage of every aspect of the imaginary (cinematic image, pop music, lifestyle etc). Consistency, perseverance, patience, state support, achievable, realistic goals: this is what is required for Greek literature to attain the position – if not quantitative, at least qualitative – it deserves in the literary world.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS