On the occasion of the 25th recent anniversary of Manos Hadjidakis death, the Turkish director and producer, Fuad Kavur, remembers the great composer and their collaboration for the film Memed My Hawk.

Fuad Kavur’ (born 1952 in Istanbul, Turkey) is a British opera and film director and producer. Kavur came to London in 1963 when his uncle, Kemal N. Kavur, was the Turkish ambassador to the Court of St. James. In 1984 Fuad produced the feature film Memed, My Hawk (also known as The Lion and the Hawk), based on the novel Memed, My Hawk by the Turkish writer Yashar Kemal. Memed My Hawk had a royal premiere in London in the aid of UNICEF. However, both the filming and screening of Memed My Hawk was (and still is) banned in Turkey by the government as “communist propaganda”. Fuad was a company director of Peter Ustinov Productions from 1982 to 1992. In 2001, he was the executive producer of Atatürk, a television documentary on Kemal Atatürk, narrated by Donald Sinden. Since 2014 Kavur has been preparing a feature film, Atatürk. In July 2013, Kavur assembled a group of artists & writers, 30 in all, to sign an open letter addressed to the Turkish Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, criticising his handling of the Gezi Park Protests in June, which left 8 people dead, 11 blinded and 8,000 injured. The signatories included Susan Sarandon, Sean Penn, David Lynch, Sir Ben Kingsley, James Fox, Sir Tom Stoppard, Christopher Hampton, Lord Fellowes, Frederic Raphael, Edna O’Brien, Rachel Johnson, Christopher Shinn, Branko Lustig, Vilmos Zsigmond and Atatürk’s biographer Andrew Mango. The letter was published as a full page advertisement in the London broadsheet, The Times, on 24 July 2013 and led to the Prime Minister Erdogan threatening to sue The Times and the signatories.

FUAD KAVUR REMEMBERS HADJIDAKIS

In 1984 I made a movie, MEMED MY HAWK, based on Nobel Prize nominee Turkish writer, Yasar Kemal, starring Sir Peter Ustinov, Herbert Lom, Leonie Mellinger, and a young English actor, Simon Dutton. The film had a Royal Première in London, in aid of UNICEF, attended by HRH the Princess Michael of Kent. The music for that film was composed by Manos Hadjidakis, and these are my recollections of it.

MEMED tells the story of star-crossed young lovers in 1930s Turkey: when a feudal Anatolian landlord wants Hatche, the young and beautiful childhood sweetheart of Memed, for his own son, the young lovers elope. Memed starts waging war against feudal landlords, and becomes a legendary brigand.

Given that the young girl, Hatche, chose her childhood sweetheart who is poor, over the feudal landlord’s son who is rich, the novel and by extention Peter Ustinov’s screenplay were deemed to be communist propaganda by the Turkish government of the day.

We were thus denied permission to shoot in Turkey, and at the last moment I had to move the production to (then) Yugoslavia.

Be that as it may, a “Young Turk” in London in the spring of 1983, I was happy as a lark. Not only had I finally got MEMED in the can, but also the “Director’s Cut”, the final stages of editing, was almost completed. Now, all we had to do was add music to the movie, and we would have a completed product in our hands. But who was going to write the soundtrack?

When I was a boy, in the early 1960s, I was smitten by an international hit, “Never on Sunday”, frequently played on the single radio station we had in Istanbul. However, I was not the only person to have fallen in love with that song, for its composer had received the Academy Award for “best original song”.

Manos Hadjidakis arrived in London on 7th April 1983 and, in the evening, I went to the Dorchester, in order to take him out to dinner. When I arrived, I found him sitting in the lobby. He looked exactly like in his photographs: a slightly chubby but good looking man with a mischievous smile. Although we had never met, he instinctively spotted me and got up to greet me.

Over the years of being involved in this business I have been lucky enough to meet various famous people. However, what I’ve noticed with the really talented ones is that they had never lost their basic humanity; they were just another human being, like anyone else. So the moment I set eyes on Manos, I knew he was one of those unassuming souls.

In fact, instead of shaking hands, instinctively, we just embraced in a “bear hug”. After a few pleasantries, we took off for Scotts – those days a fashionable restaurant in Mayfair.

Into our second dry martinis, Manos wanted to know how come a Turkish producer, making a movie based on a Turkish classic, ended up approaching a Greek composer. I replied,

“You are not just any Greek composer”, adding, “when I was ten, I was already singing – ”

“I know, they call me Mr Never On Sunday”, looking as if he wished the label would just go away. Then, he added:

“You know, I didn’t even go to Hollywood to pick up the Oscar…”

Obviously, Manos would rather be known for his “Gioconda’s Smile” which, when it was first performed, caused a sensation in the world of classical music. As such, he felt, he legitimately belonged with the group of 20th century composers such as Leonard Bernstein, Phillip Glass, George Gershwin or Pierre Boulez… Then he changed the subject:

“There are two composers in Greece: one is a communist, the other is gay”, adding, as if to thank God, “I … am not the communist.”

Having got that out of the way, Manos relaxed. Now, he wanted to know what made me chose Yugoslavia to make MEMED. I replied:

“Sadly, the Turkish government takes an equally dim view of communists”, adding, “worse still, those they deem to be communists...”

The rest of the evening was spent chatting about music. Given that before movies I used to be an assistant director at the Royal Opera House, music had always been my first love, so we had plenty to discuss. Soon, Manos was telling me about “Rebetiko”, a kind of music disapproved by Greek middle classes, on which he had based his own “Song Cycles”:

“Rebetiko belongs to ‘undesirable people’ – opium smoking, with no fixed address…”

Then, with an afterthought, Manos added,

“Most Rebetiko musicians fled to Greece, in 1922, after the fall of Smyrna…”

“I knew, Turks had to take the blame for it”, I commented, jokingly.

“Or, the credit ”, Manos replied, with a smile.

The next day, at 11 am, we reconvened at a ten-seat screening theatre, in Wardour Street, Soho. Those days, prior to the digital revolution, the only way for producers to show their work in progress was to use one of those mini cinemas, rented by the hour.

When Manos and I arrived, we found Peter Ustinov and our editor, Peter Honess, already waiting for us. Of course, as Manos had also written the music for TOP KAPI for which, in 1963, Peter had won his second Oscar, they already knew each other. After the usual pleasantries, the lights were dimmed and we got down to watching the Final Cut of MEMED MY HAWK.

After 110 minutes, following many adventures, when the brigand Memed killed the tyrannical feudal landlord, Abdi Agha, the lights in the theatre went up again. Now, I was discreetly studying Manos, to figure out his reaction to the movie he just had seen. He went over to Peter Ustinov and, speaking in French, said:

“C’est merveilleux, je vous félicite!”

Wheelers on Dean Street in those days, was a favourite haunt of film business in London. During lunch, Peter Ustinov and Manos discussed the scenes where music was needed. Peter, who could never help performing if there was an audience, immediately started acting all the parts, then humming tunes to describe the kind of music he wanted.

By the time we were having desert, Peter had finally managed to reach the end of the story, although he was still singing the music for the final scene. Manos however, having been treated to the same movie twice in one day, finally interjected:

“Je comprends ce que vous voulez”, meaning he had got the message.

As we were parting company, our editor gave Manos a VHS copy of MEMED, a novelty for the early 1980s. Finally, Peter asked how long Manos needed to write the music. Without hesitation, he replied,

“Six weeks.”

With that, saying he wanted to do some shopping, Manos disappeared. It was at that moment, I had a premonition that things might not go totally according to plan. So, I decided to get some insurance policy.

Bela Bartok, the Hungarian composer, was also an ethnomusicologist. As such, in 1936, he travelled to Turkey and toured Anatolian villages, collecting Turkish folk song themes. This gave birth to his book “Turkish Folk Music From Asia Minor”. Given that Foyles, the famous bookshop, was a stone’s throw from Soho, I decided to take a walk to Tottenham Court Road.

On our last evening, I gave Manos Bela Bartok’s Opus Magnum, casually mentioning that should he get stuck for a theme, there were plenty in that book; that was my insurance policy.

Weeks passed quickly. Indeed, at the end of the fifth week I called Athens, and asked Manos how it was all going. He sounded cheerful and satisfied. I asked if I should book the recording studio, and I was given the green light. So, the next day, I booked the legendary Abbey Road Studios for three sessions, where the Beatles had recorded all their albums.

Weeks passed quickly. Indeed, at the end of the fifth week I called Athens, and asked Manos how it was all going. He sounded cheerful and satisfied. I asked if I should book the recording studio, and I was given the green light. So, the next day, I booked the legendary Abbey Road Studios for three sessions, where the Beatles had recorded all their albums.

Booking the orchestra was a different ball game. In London, most recordings for film scores were performed by “session musicians”- players belonging to the LSO, RPO, or BCC Symphony but were free in the mornings.

A dear Turkish friend of mine, Rusen Gunes, the “First Viola” at the Royal Opera Orchestra, whom I knew from my assistant days at Covent Garden, became handy. When I called him, and explained my problem, Rusen told me what I needed was a “Fixer” – someone who assembled available players from main London orchestras for session work. However, I was advised, the “Fixer” would need the precise number of musicians required- how many strings, woodwinds, brass etc.

So, I called Athens again. However, this time, I found Manos less than forthcoming. Indeed, as we went through the instruments, he became unmistakably ill at ease.

“Clarinets?” “One, no, make it two.” “Oboe?”, “Probably one”, “Bassoons?”, “Qu’est ce que cels veut dire?” ,“Cor Anglais.”, “On va voir.”

When he felt cornered, Manos resorted to French, obliging, I assume, his interlocutors to converse in a language which was not theirs, putting them at a disadvantage and hoping that whatever he wished to obfuscate would get “lost in translation”. Still, having studied at the French Lycée in London, I managed to navigate through this Machiavellian ploy. So, I finally got a list: 47 instruments in all.

Of course, music business being what it is, one had to agree on players’ salary with the Musicians Union. As for Abbey Road Studios, they simply got a cheque for all the sessions. Both payments were on non-refundable basis.

Another week passed, and I still had not heard from Athens. Now, I was distinctly getting cold feet. I had to warn Peter Ustinov that in five days we were due to go into Abbey Road; but, should Manos fail to show up, we were in for a mighty loss.

The next morning, on the British Airways flight to Athens, I was still assessing the consequences, should Manos decline to come to London. Apart from taking a considerable financial hit, we would never make it to Venice Film Festival – unless I could get the Italians to accept a movie with no music on it.

By the time I checked in at the Athens Hilton, it was already dark. So, I immediately dialed Manos’s number. After a long ring, the call was finally answered by a man who spoke little English. After I introducing myself, I told him I was in Athens and wished to speak with Mr Hadjidakis.

“Monsieur Hadjidakis very ill. He go to Mykonos to be better.”

My worst fears were confirmed. Now, I had to take the bull by the horns.

The cab ride from the Hilton to Rigilis, where Manos lived, took less than ten minutes. His address turned out to be a small block of flats. I entered the dimly lit building, and climbed up two floors. Finally, I was standing at the door of the greatest composer in Greece. I took a deep breath and rung the door bell.

« Bonsoir, entrez s’il vous plaît »

There he was, Manos, in a blue silk gown, in a Noel Coward pose, smoking with a long cigarette holder. There was hardly any point in embarrassing him with smart remarks such as, “I thought you were in Mykonos…”

Manos led me to a small dimly lit sitting room with an ornate Louis X1V desk, couple of armchairs, and a Steinway grand. After a few polite exchanges, finally, pointing at the piano, I asked if he would care to play something. Taking a puff from his long cigarette holder, Manos replied,

« Je cherche toujours le thème principal... »

He was still looking for the main theme!

Then, something quite extraordinary happened. Suddenly, I sprung to my feet and hummed a tune. In fact, it was a four note melody, based on the four syllables of the Turkish title of Yasar Kemal’s novel, INCE MEMED. Those four notes, then repeated, as an echo, “Ince Memed … Ince Memed…” and moved on to its dominant; then, with a twist, resolved back on the tonic. Given Turkish music had one characteristic which the Western music did not possess – quarter intervals; so, my tune was in a minor key. As I finished humming, jumping out of his seat, Manos declared:

« Voila le thème principal du film! »

With that, he sat at the piano and started playing what he had just heard- naturally embellishing it with lots of harmonic modulations and variations. Obviously, I had removed his “writer’s block”, and now he was totally immersed in enthusiasm.

Manos played for half an hour, occasionally stopping and jotting down what he just had performed. Exhausted, he finally stopped, and said:

“Ça va être formidable, venez demain, à Midi.”

On my way back to the Hilton, I realised, in Manos’s tiny flat, something quite extraordinary had taken place – which could never be explained neither by any branch of science, nor logic. Moreover, from that moment on, we had connected, and that was the beginning of our real friendship.

The next day, as asked, I arrived at Rigilis at noon, on the dot. Ebullient, Manos greeted me,

“Bonjour, cher ami!”

As I entered the sitting room, the first thing I noticed was piles of manuscript paper, scattered around, on top of the Steinway, and ashtrays filled up with cigarette buds.

“Je me suis couché à six heures…”

He had gone to bed at 6 am. Then, he sat at the piano and started playing more music which sounded absolutely riveting. There were unexpected modulations of harmony, changes of rhythm- with syncopations, giving an Anatolian flavour to the tunes. As he played on, he provided a running commentary:

“This is when they run to the mountains…”

“Now, they’re making love...” Then, totally exhilarated, Manos announced,

“We will record the music in Athens!”

However, there was still a small detail to be resolved, namely the cost of the ill-fated recording sessions in London: a 47 piece orchestra, and the Abbey Road Studios, all paid in advance, on pay-or-play basis; in plain English, strictly non- refundable. Still, as if he read my thoughts, Manos said,

“Ne vous en faites pas, je vais payer tout moi-même.”

Manos was offering to pay for the cost of the recording sessions, now to take place in Athens, out of his own pocket!

While this was a relief of sorts, despite the pledge being made, in French, I could not help wondering if he really could afford to make such a grand gesture.

A few days later, a certain Mr Zographos turned up at the Athens Hilton. A top agent in the business with a poker face, beside Manos, he also represented Vangelis, who had just won an Academy Award for “Chariots of Fire”. Zographos drew up a one page “Deal Memo”, stating that the entire cost of the sessions, the orchestra and recording in the studio was to be met by Hadjidakis, as long as his fee for writing the music for MEMED MY HAWK remained intact. We signed the deal by the swimming pool, over some Caesar salad, washed with Retsina wine.

From that day on, my sojourn in Athens acquired a routine. Each day, at five pm, I would show up at Rigilis, and he would play what he had written during that day. Some days, he would also run the relevant scenes on VHS, on his large TV set, while accompanying the action on his piano. In a way, this reminded me of cinemas in 1920s, when silent movies were accompanied by a pianist, under the silver screen.

Occasionally, Manos would crush the manuscript paper, and start all over again- rapidly jotting down new ideas. It was then I realised Manos had already “heard” the music in his head, and was capable of notating it, without having to play it on the piano.

Some evenings, we would adjourn to a restaurant. Of course, Manos knew his Athens, and enjoyed sharing with me his favourite haunts. However, there was one which appealed to me the most, “Gerofinikas”. Apart from its delicious fresh fish, it had a trade mark: an enormous oak tree, right in the middle of the restaurant, which, through a hole in the ceiling, climbed up to the skies.

Gerofinikas soon became our favourite haunt. So, most evenings, after Manos played for me his day’s work, we would adjourn to Gerofinikas to sample their sea food and other Greek delicacies.

Finally one day, pointing to a pile of sheet music on his piano, Manos announced:

“Nous sommes prêts.“

We were done. He had written one last piece of music, a tango, which was to accompany a dinner scene, when Abdi Agha, (Peter Ustinov), visits a more sophisticated and powerful feudal landlord, (Herbert Lom), in order to enlist his help to apprehend the brigand Memed.

As Manos sat at his Steinway, he casually excused himself, as he had not had enough time to work on that particular piece, for earlier he had lunched with Konstantinos Karamanlis, the president of Greece. With that, Manos proceeded to play his, yet un-perfected, Tango.

By the time he finished I was almost moved to tears. This was one of the most voluptuous, lush, exciting tangos I had ever heard – on a par with “La Cumparsita”. It was obvious that musically there was nothing Manos Hadjidakis could not do. If he felt like writing a Tango, momentarily he became Argentinean.

“When do we record?”, I asked.,“Now we have to orchestrate”, Manos replied.

At that point, I could have easily killed him. I already had been in Athens four weeks, and we still could not start recording. Of course I realised, one could not just put a piano score in front of a 50 piece orchestra, and ask them to perform from it! Noticing my despair, Manos said,

“Ne vous en faites pas, je vais faire venir mes assistants.”

So, for the next two weeks, the small apartment became a beehive. Some days, there were three or four “assistants”, young men, in their early twenties, busy copying scores.

Given there was not enough space, some of them had to sit on the floor, with manuscript paper on their lap, copying music. Like a headmaster, Manos supervised the proceedings, looking down the shoulder of each of these “assistants”, and occasionally correcting them.

“Mi bémol, Stavro!”, Finally, one evening at Gerofinikas, Manos announced: “Voilà, c’est faite.”

It was done! The orchestration was completed. So, Manos announced, we could start recording, the next day- at EMI Studios Athens. I asked him, what time:

“À minuit.”, Midnight? Was he joking?, “En Grèce, ça se passe comme ça.”

That was how it was done in Greece! Apparently, unlike in London, where there are number of orchestras, the LSO, RPO and BBC Symphony to name a few, in Athens there was mainly one orchestra and, at present, they were playing for the Opera. Moreover, given during the day they rehearsed, the only time they could do session work was after evening performances had ended. Then, one had to allow time for them to travel to EMI Studios- near the airport. This gave the term “Moonlighting” a totally new dimension.

The next day, when I got to the EMI Studios, at 11:30 pm, the orchestra was already there, with Manos at the conductor’s podium, talking to violins.

A quick head count revealed this was a 52 piece band – larger than the one I had booked in London. I could not help feeling sorry for Manos, for this must be costing him an arm and a leg – even in Drachmas.

I have always loved the sound of an orchestra warming up, with various instruments doing scales, arpeggios, or simply tuning up. To my ears, this cacophony conjures up the magic word of music! Now, there was palpable electricity in the air, for the orchestra was about to record a freshly written piece, to be conducted by the composer himself- no other than Manos Hadjidakis.

Finally, Manos picked up his baton, and with “Pame pedia” (Hit it, kids), he gave the downbeat, and up came the C minor chord with the “Memed theme”.

By now, I had been in Athens almost five weeks. Moreover, having arrived one night at Manos’s apartment to find a composer with a writer’s block, I had hummed a tune – which, to this day, I have no idea whence it came from, and there we were… Now a full symphony orchestra was recording it, under the baton of a world famous musician, and what’s more, to be immortalised on the silver screen. This was nothing short of a true miracle of God.

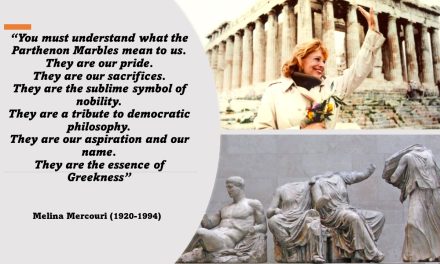

The Royal Premiere of MEMED MY HAWK. Fuad Kavur with the Princess of Kent

The Royal Premiere of MEMED MY HAWK. Fuad Kavur with the Princess of Kent

As I settled down in the sound proof gallery, I noticed a young and attractive Greek woman, sitting with the recording engineers, humming the MEMED theme. Still, thinking she might be a friend of one of the players, I did not pay any attention to her.

However, the following night, there she was again. Only this time she had the sheet music, with her, and she was distinctly sight reading it, and so I discreetly approached the podium and asked Manos if he knew who the young woman was. Putting his baton down, he replied:

“Ne vous en faites pas…”

It was all very well telling me “don’t worry about it”, but right through the session, she kept humming the music of the movie. Moreover, every time she caught me observing her, (I assumed she knew I was the producer), she smiled back. I smelled something fishy, but could not lay my finger on it.

It was only as we were being driven back to Athens, in the wee hours, that I finally managed to elicit from Manos the truth. Following the debacle in London, which had landed us up in tens of thousands of pounds in non-refundable deposits, and in order to fund the sessions in Athens, Manos had made a Faustian deal with a Greek record producer. That is, the man’s protégée, the young woman at the studio, would sing “the theme song” over the title sequence of the movie!

“Vous appartenez à une famille des ambassadeurs, soyez diplomatique.”

Now, Manos was suggesting, “You come from a family of diplomats, don’t rock the boat.” Not wanting to have a confrontation, in a limo, in the wee hours, I decided to drop the subject.

However, first thing the next morning, I called Mr Zogrophos, Manos’s mega agent who represented all the Good & the Great in the music business in Greece. While claiming he knew nothing about Manos’s Faustian deal, he did give me a name and a phone number, mentioning that the big shot impresario in Greece might be behind the “arrangement”.

The “big shot impresario” turned out to be an elderly Greek gentleman. There was a large photograph of a young woman on his desk, whom I immediately recognised to be the girl at the studio. The man freely confirmed he was indeed funding the recording sessions for MEMED. Then, looking at the photograph on his desk, he declared:

“She will win Manos his second Oscar.”

I have always been aware that movie business is a mixture of dreams and reality; but now, how could I possibly shatter the illusions of this elderly Greek gentleman, by revealing to him that there would be no theme song in Greek or any other language, and it was unlikely that Manos would even be nominated for a second Academy Award. Yet, it was my unenviable task to acquaint this affable Old Boy with the facts of life.

By the time I finished, visibly pained, for a moment he remained silent. Then, trying to keep the dream alive, at least for his young protégée, he said:

“Let her record the song; later, you decide to cut it.”

I explained, as tactfully as possible, although such a solution might afford him a few more months of bliss, it would ultimately end up in tears; for, when the movie was released she was bound to notice there was no song on it performed by herself or by anyone else. In conclusion, I could not be a party to such a ploy.

Trying to mask his anguish, he finally gave in:

“You have become too English…”

What also transpired at this painful meeting was that Manos had “sold” the Greek rights of the music to this elderly gentleman. However, this time heeding Manos’s advice, I decided “diplomacy” was the wiser option. Consequently, in order to leave the Old Boy with something to hang on to, I decided to overlook the obvious invalidity of such a transaction. Besides, we had two more recording sessions to complete.

Mercifully, a few days later, we were done. So, having arrived in Athens six weeks previously, without a single note of music on paper, I now had five boxes of 2” tapes, with the complete soundtrack of MEMED MY HAWK.

Throughout history, Greco-Turkish relations have never been a bed of roses. Although not directly related to Manos, I cannot help but recount an incident which took place on my last night in Athens.

To mark the occasion, I had invited Manos and his young assistant who helped copy the score, plus a few musicians to Gerofinikas – the delightful fish restaurant which had become our usual haunt.

Given this was a “thanks giving” and a farewell dinner, ouzo and wine flowed, and we were all quite merry. When the Maître d’ came over to ask who would take coffee, Manos whispered into my ear:

“Whatever you do, don’t say Turkish coffee.”

At that point, I do not know what got into me but, in a loud voice, I said to the Maître d’,

“I’d like some Turkish coffee.”

To mitigate, Manos intervened,

“Monsieur is Turkish…”

What ensued was quite extraordinary, and it astounded all present, including myself. The Maître d’, speaking in perfect Turkish, asked me what part of Turkey I was from. When I told him from Istanbul, he replied:

“We used to own a restaurant in Istanbul. Then, in 1964, there was some trouble in Cyprus, and we were all kicked out… So, we came here, and opened this place.”

Then came the most poignant part of his story: “I was born in Istanbul, Turkey was my home…”

I asked him the name of his restaurant, and when I he told me I had another shock.

“Fidan. It was in Tarabya”.

In the early sixties Istanbul, sitting on the shores of the Bosphorus, in the chic Tarabya resort, “Fidan” was the most popular fish restaurant in Istanbul.

“I used to go there with my parents”, I replied.

“May I ask what your father’s name was?”

When I told him, he could not believe his ears.

“I remember him well! A tall gentleman, with slightly balding head. He had two brothers, both ambassadors.”

“That’s the one”, I replied.

Upon this, the Maître d’ put his arms around me, and gave me a huge bear hug.

“I love Istanbul, if I could, I’d go back tomorrow...”

Given this conversation took place in Turkish, Manos was observing the goings on with total disbelief. He had advised me not to mention “Turkish coffee”, and I did. Obviously, by now, Manos was expecting Maître d’ and I exchanging blows.

Whereas, now, the man was hugging me as if I was his long lost brother. Finally, Manos spoke:

“Mais, au nom de Dieu, que ce qui se passe?”

So, I explained everything. Manos shook his head, and whispered into my ear,

“You crazy Turks…”

To this day in 2019, I strongly believe that “repatriating”* the Greek population was an objectionable mistake that Turkish administrations committed, while ultimately the only losers of this ill-conceived policy were the Turks themselves. Indeed, in my opinion, having a Christian community only enriched the fabric of the Turkish society.

Moreover, if Turks had a degree of common sense, they should have demolished the minarets surrounding Hagia Sophia and donate the cathedral to the Orthodox Patriarch residing in Istanbul: the Catholics have St Peter’s at the Vatican, and it would have been apt for the Orthodox Christians to have Hagia Sophia as their main place of worship. Indeed, Kemal Ataturk had taken the first step, when he made Hagia Sophia a museum. Sadly, to this day, no Turkish administration had the wisdom to follow in his footsteps.

As I was flying back to London, I reflected on the seven weeks I had spent in Athens: if I had a chance to do it again, I would not have had it any other way. Indeed, if the recording sessions had taken place, as originally planned, in London, we never would have had the vibrant, lively, spontaneous results, captured on the 2” tapes, now sitting in the five boxes on the seat next to mine.

Moreover, I had the unique privilege of witnessing a genius at work. I also realised they could not be judged by the rules that apply to ordinary mortals.

Finally, this story does have a Happy Ending. Apart from the fact MEMED MY HAWK had a Royal Premiere in London, and its soundtrack album was released then as a vinyl record, later another record was released in Greece, with a most talented artist, Elli Paspala, singing the MEMED theme.

I would like to think that the elderly gentleman who funded the recording sessions in Athens did, after all, manage to hang on to his young protégée. So, as the old English saying goes, “All’s well that ends well.”

*he means the deportation of the Greek citizens in Turkey that took place between 1964-1966

The story was first published on Sigma Turkey . Photos taken from Fuad Kavur’s personal archive.

Read also: Manos Hadjidakis: The grand poet of Greek music