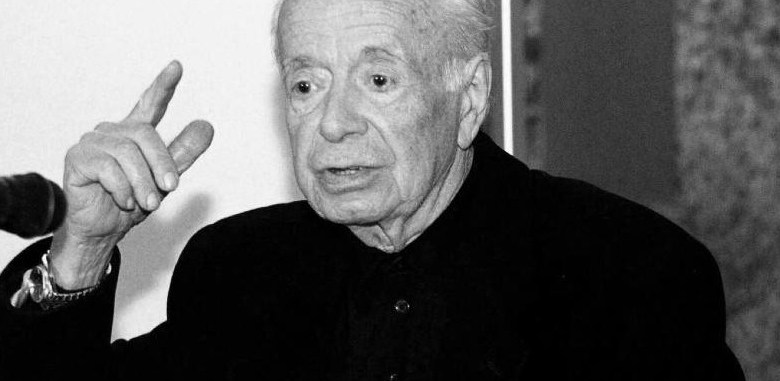

One of the most significant Greek prose writers of the post-war generation, Antonis Samarakis, is credited with being the most widely translated Greek author after Nikos Kazantzakis, with his works being translated in over 30 languages. Often referred to as the Greek Kafka, he is one of the most widely read Greek writers, both in his native land and around the world.

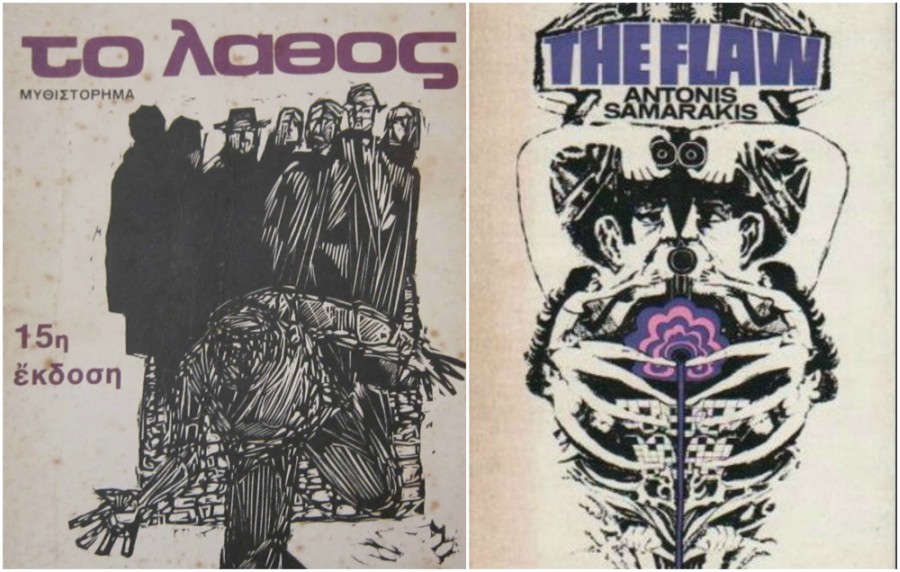

Called “a real masterpiece” by novelist Graham Greene, and “a powerful work” by playwright Arthur Miller, Samarakis’ novel To Lathos (The Flaw, 1965) was eerily prophetic of the military dictatorship that was shortly to be established in Greece. Translated into English by Peter Mansfield and Richard Burns in 1969, the novel deals with the fate of a suspect detained in an unspecified police state; a plan is devised to make him attempt to escape, thereby proving his guilt, or confess to his anti-state crimes under interrogation.The flaw is the plan’s failure to allow for the human factor, the fellow-feeling that the interrogator develops for the suspect during their time together. Oppressed and oppressor come face to face with their deepest human feeling, locked in a game of psychological skill.

As the plot slowly unravels, so do its main players. Professor Roderick Beaton comments that “the flaw turns out to lie in innate human goodness, for which the “perfect” totalitaritan system had failed to allow […] The reader comes away warmed by the imagination that could create these people, but not always convinced that the world can be so neatly divided between decent individuals and inhuman systems“.

Part thriller and part political satire, The Flaw is as powerful today as it was when first published. It is the best-known work of Antonis Samarakis and has been translated into more than thirty languages. The novel was awarded the coveted prize of the Twelve in Greece in 1966 and the Grand Prix de la Littèrature Policière in France in 1970. It was also turned into a successful film by Peter Fleischmann in 1974.

Samarakis’ themes, which found a receptive readership particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, were the helplessness of the ordinary person in the face of growing state power, the nuclear threat, the loss of ideals, public corruption and the alienation of the individual in an uncaring, consumer society. “Samarakisʼs writings are international,” Professor Andrew Horton comments, “because the serious problems of our times are general and universal and not limited to any particular nation.” Indeed, Samarakis’ work is characterized by the element of social denouncement and reflects his personal worries about the present and future of modern societies. He wrote in simple language and natural style and approached his issues from an intense anthropocentric point of view.

The protagonists of his stories are ordinary people facing crises in their lives and beliefs – a widow bringing up a consumptive child in slum conditions, a priest tending a dying man, a soldier unable to kill the enemy with whom he feels a common bond, a man who seeks to regain his childhood innocence by buying the house in which he spent his early years. Their situations lead to a shattering of hopes and ideals or to a new affirmation of human values. What is significant about Samarakis, says Horton, is that “he remains that rare writer who speaks for the average, simple person and who sees the dangers in a modern society for totalitarianism, dictatorships and such that eat away at allowing people to live simple lives.“

As in much of Samarakis’s work, the characters are anonymous, the style fragmented and plain, sparing in description, but racy, with unexpected twists and an often caustic humour. His protagonists’ agonised states of mind are depicted with frequent repetitions of words and phrases, often tending to stream of consciousness.

Antonis Samarakis was born in Athens and studied law at Athens University. A civil servant in the labour ministry, he resigned in 1936, when General Metaxas imposed a fascist-style dictatorship on Greece, but resumed his post in 1945. During the German occupation, he joined National Solidarity, a precursor of the main leftwing resistance organisation, the National Liberation Front. In 1944, he was sentenced to death for his resistance activities, but managed to escape and go into hiding.

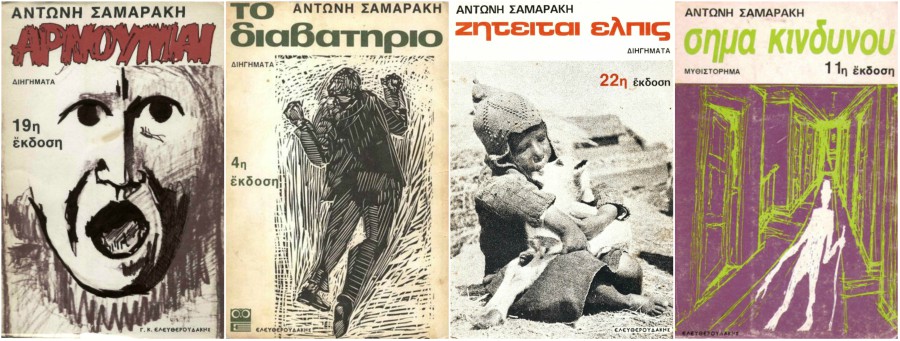

From an early age, he wrote poetry for literary magazines and anthologies. But in the 1950s, he made the decisive turn to prose fiction, publishing his first collection of short stories, Ziteitai Elpis (Hope Wanted) in 1954.

Samarakis’ first novel, Sima Kindunou (Alarm Signal, 1959), and second collection of short stories, Arnoumai (I Refuse, 1961), which won the state literary prize for short stories, developed the same themes and further established his reputation, enabling him to resign from the civil service in 1963 and devote himself to fulltime writing.

His longest short story, The Passport, reflects his experiences under the military dictatorship of the 1960s, when he was denied a passport unless he wrote something favourable to the regime. The story is not merely autobiographical but generalises, in a manner reminiscent of Kafka, the plight of the innocent victim of a totalitarian regime.

Samarakis has had more critical attention and commercial success in continental Europe, especially Germany, Scandinavia and France, than in Britain. His work was held in high regard by other notables, as well, among them Arthur Koestler, George Simenon, Agatha Christie, and Luis Bunuel.Translations of his works into more than 30 languages, as well as the stage and screen adaptations, attest to his ability to address issues of common humanity. Formal recognition of his work as a whole came in 1982 with the award of the Europalia Prize and the Knight’s Cross of Arts and Letters in 1995

Samarakis represented Greece at conferences of Unesco and the International Labour Organisation, whose missions he also took part in. He was a goodwill ambassador for Unicef, organised an annual youth parliament in Greece, and, in 1991, was designated as his country’s cultural ambassador for Mèdecins sans Frontières. After his death in 2003, «”European Day of Languages 2006″ was dedicated to Samarakis, “a global man”.

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE