Persa Apostoli is a graduate of Medieval and Modern Greek Studies at the Universities of Athens (B.A., Ph. D) and King’s College, University of London (M.A.). She works as an Associate Lecturer at the Hellenic Open University (Department of European Studies: 2003-2010, Department of Hellenic Studies, 2010-). She has also taught Modern Greek and Comparative Literature for the Universities of Peloponnese and Patras and has participated in several Research Programmes.

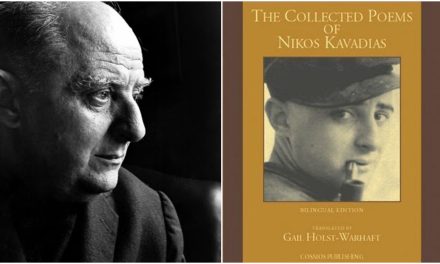

Major publications: “The European Itinerary of the Picaresque Novel and its Traces in 19th Century Greek Literature (Transformation and Continuity)” (Neohelicon, 2004); “The Second Acknowledged Model of Gr. Palaiolugue’s O Polypathis (1839): F. Bulgarin’s Ivan Vyzhigin (1829)” (Comparaison, 2006); “Women’s publishing activity (arts’ and literary periodicals 1900-1940): the cases of Artemisia Landraki and Kornelia Preveziotiou”, in S. Denissi (ed.), Women’s artistic and literary activity in Greek Periodicals 1900-1940 (Gutenberg, 2008); Marietta Giannopoulou-Minotou, The authentic story of Pope Joan (ed.) (Periplous, 2011); The Picaresque Novel and its Traces in 19th Century Greek Literature. From “Hermilos” to “Pope Joan” (Artemis, 2018). She is a member of the Greek General and Comparative Literature Association and the International General and Comparative Literature Association. Principal research interests: 19th and 20th century Greek prose-writing, comparative literature, Greek literary journals and women’s writing.

Persa Apostoli spoke to Reading Greece* about her latest writing venture, noting that “the purpose of the book was to act as an introduction of Greek readers into the history of the picaresque novel” and “remedy the lack of a broader research on the topic in Greek, despite the extensive international bibliography”. She comments both on the origins of the picaresque novel in Greece, and the main features of the picaresque novel and the pícaro, explaining that among pivotal picaresque themes are “the disparity between perception and reality and the alienation of humans from the world that surrounds them”, and that “the picaresque myth presents a world turned upside down, where all values are reversed and reality becomes slippery”.

Asked about the main challenges researchers in Greece are faced with, she notes that although “most Greek academic libraries have been modernized and enriched”, “research in Greece continuous to be an arduous and poorly paid, if not a self-financed occupation, especially as regards the field of Humanities”. She concludes that “a long-standing strategy on the part of the official state, as well as various initiatives by Greek and foreign institutions…which somehow act as cultural ambassadors, could contribute to a more effective promotion of modern Greek literature in the international book market”, while “priority should be given to the financing and promotion of translations, along with the participation in international fora and book fairs, cooperations and further actions”.

Your latest writing venture, The Picaresque Novel and its Traces in 19th Century Greek Literature, was shortlisted for the O Anagnostis Literary Review Awards 2019. Tell us a few things about the book.

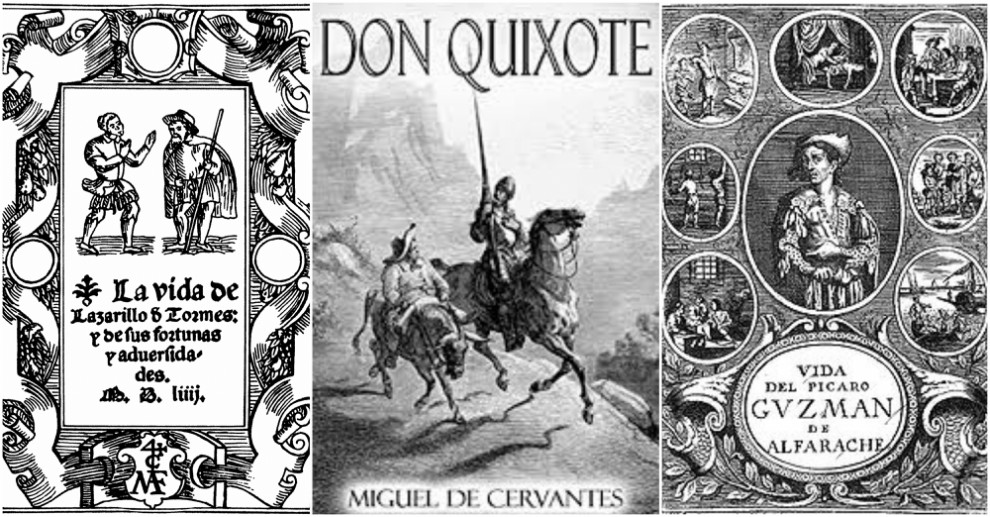

The book is a revised and further enriched version of my doctoral thesis submitted to the University of Athens in 2003. It aims to remedy the lack of a broader research on the topic in Greek, since, despite the extensive international bibliography, this bibliography was mostly unknown to the Greek public and the few other Greek scientific articles were focused on specific works or specific aspects of the genre. Thus, the purpose of the book was to act as an introduction of Greek readers into the history of the picaresque novel, a literary genre which emerged in 16th-century Spain and was spread both in European and non-European countries until at least the mid-19th century (some researchers support that it has survived to the present). In this context, the first part of the book briefly lays down the milestones vis-à-vis the appearance and development of the picaresque novel, its predecessors and origins, as well as its primary traits.

At the same time, the book aspires to act as an introduction into the history of the reception of the picaresque genre by international literary critique from the moment it first appeared until the present day, a history equally fascinating. The book discusses how the socio-political, ideological and aesthetic changes that took place throughout the centuries and from country to country decisively determined this reception intertwined with the evolution of the genre and lays special emphasis on the role of translations and the adaptations to the respective languages. It also follows the various different aspects of the picaresque novel that have been featured within the framework of different theoretical approaches and methods, which are chronicled in the book, accompanied by a detailed and up-to-date bibliography.

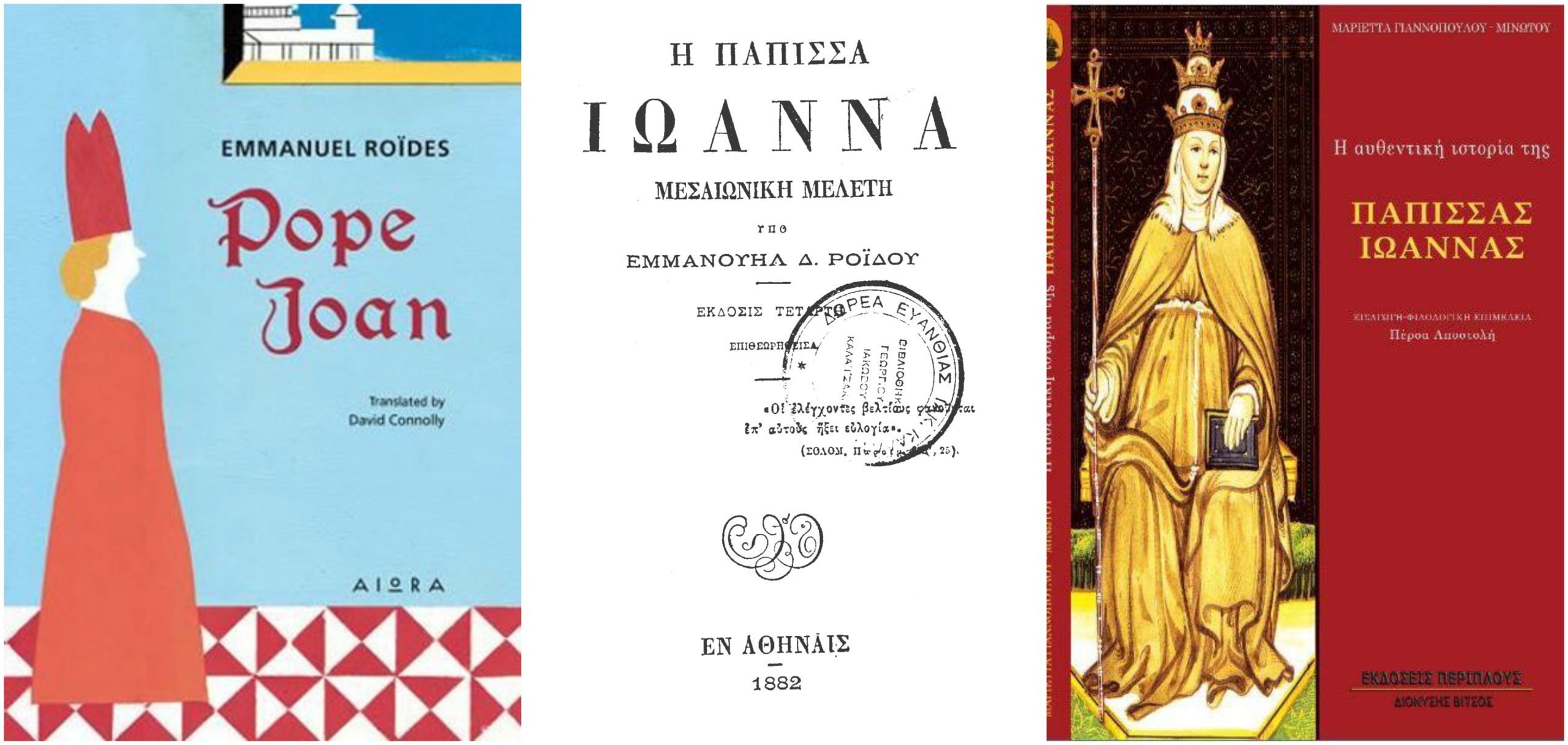

The second part traces the origins of the picaresque novel in the Greek-speaking world during the abovementioned period: whether translations took place, what kind of respective references and comments appeared in the press, in forewords, dictionaries and so on, whether there exist foreign editions of that time in the National Library and the Library of the National Parliament that prove some kind of potential interest of Greek readers in the genre. There is also a mapping of the Greek prose landscape through the examination of typical prose texts that “converse” with the picaresque novel, starting from the fist decades of the 19th century until the publication of the emblematic The Pope Joan by Emmanuel Rhoides. The aim is not just to trace convergences and divergences from the picaresque novel, but to highlight various important features of these works, for example the way they ‘converse’ with other traditions, such as Fool’s literature, Mock-heroic Poetry, the Lives of Saints etc, the respective rhetorical means, the various sides of reality that come under scrutiny, as well as their thematic, ideological, aesthetic and other affinities.

Despite the increasing international bibliography on the picaresque novel, the genre remains virtually unknown in the Greek literary world. How did the picaresque novel reach the Greek world of letters in the 19th century?

Up until the 19th century, translations directly from Spanish were scarce. Thus, works belonging to the Baroque era, such as the emblematic Don Quichotte or the El Criticón, were translated into Greek through a French or Italian intermediary. Despite the fact that the Spanish picaresque novels had already been widely translated in many European languages, including our neighboring Southeastern European countries (e.g. Romania, Russia), no Greek translations of Spanish picaresque novels either from the prototype or from some French, Italian or other translation have been traced. What is traced, however, is a great number of Greek translations of the popular in many countries French representative of the genre, Gil Blas by Alain René Lesage. Thus, in Greece the picaresque genre seems to have become known mainly through this later, modified, picaresque novel, which was not only loved by readers but also acted as a model for many Greek writers, such as Grigorios Palaiologos and his novel O Polypathis [Τhe Man of Many Sufferings] , the “Greek Gil Gas”, as the author himself had called it.

Which were the main features of the picaresque novel?

The features of the picaresque novel have not been uniform or steady from text to text, from country to country or from one era to the next. Primarily a protean genre, it may relate to the Bildungsroman, the novel of manners, the social satire, the romance and other types of prose fiction.

In general, the picaresque novel constitutes a pseudo-autobiographical narration structured in episodes, which follows the adventures of a rogue wandering from place to place and among different social classes, while striving to survive in an environment which is in essence hostile towards him and contradictory. Events are presented from the point of view of the hero itself, an unreliable narrator, who, in order to justify his acts, sometimes discloses and sometimes hold things back, enticing readers into a game of deception, the same way the hero interacts with the people he meets. The main narration is often interpolated with narrations of secondary characters. This fact combined with a language that is interspersed with puns and phrases open to multiple interpretations, adds to the text’s polyphony, bringing forward pivotal picaresque themes, such as the disparity between perception and reality and the alienation of humans from the world that surrounds them.

In addition, although picaresque texts contain many realistic elements vis-à-vis the representation of social life, the causes or dimensions of a problem are often distortingly overstated while descriptions are characterized by exaggeration, which tends towards the grotesque. Finally, the world is depicted through scenes that focus on the lowest ranks of human life, where everything in translated in material terms, thus demonstrating its disparities and imperfection. In this way, the picaresque myth presents a world turned upside down, where all values are reversed and reality becomes slippery.

Starting with Don Quichotte by Cervantes, which, as you argue in the book, provides us with one of the first descriptions of the genre’s hero, which are the main traits of the pícaro?

Indeed, in one of the book’s most representative scenes, Don Quichotte meets some chained convicts, who are forced into the galleys. One of them tells the hidalgo that he has written down his adventurous life in a book that will likely surpass both the Lazarillo de Tormes and the Guzman de Alfarache (the first Spanish picaresque texts). Through this scene, Cervantes offers, of course in his own perspective, an early description of the pícaro and the picaresque genre.

The pícaro is usually a young person of low social status and a questionable origin, who tries to face the adversities of life on his own. He stands on the margins of society, aiming neither to confront nor change it, and has no high ideals since he is only interested in satisfying his hunger. Throughout his course of life, and especially during his first steps, being inexperienced and gullible, he falls victim to cunning and malicious people, a fact which introduces him to the world of deception. Easily adjustable and inventive, he resorts to whatever means (both legal and illegal), he often changes occupations, places, even his appearance and doesn’t seem to settle anywhere. Therefore, he is not a one-dimensional hero since he often appears to be volatile and inconsistent, while his character and his behavior are presented and interpreted in various ways according the general stance and the purposes of each writer.

What about the most typical picaros in the respective Greek novels?

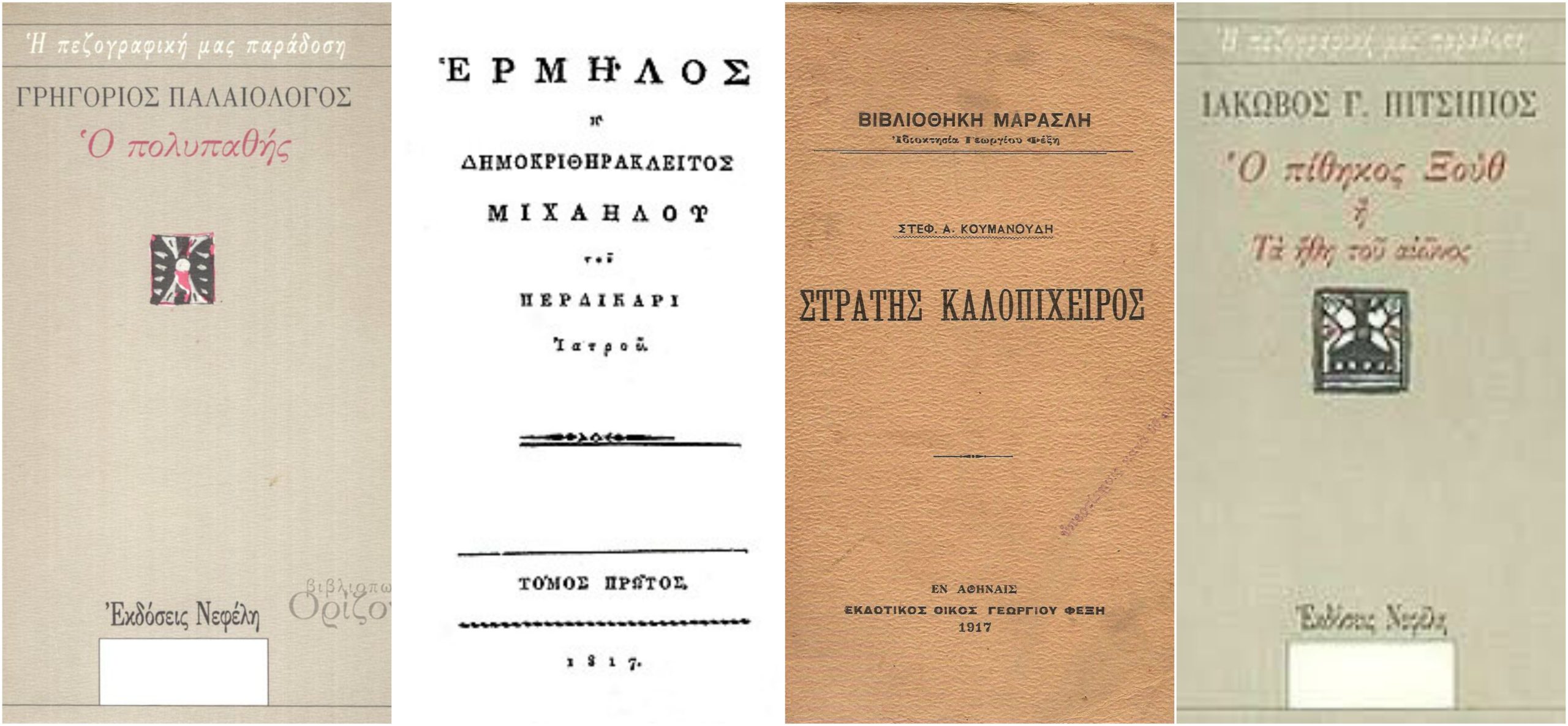

In Ermilos by Michail Perdikaris, the hero – not himself a typical pícaro – transformed to a donkey watches from his position as a pack animal the picaresque adventures of the fisherman Meliras, who pretends to be a doctor. Similarly, in the unfinished novel Xouth the Ape by Iakovos Pitsipios, the interest lies in the ideologically charged fact that the role of the transformed servant-ape is played by the known mishellene Jacob Salomon Bartholdy. In The Man of Many Sufferings by Grigorios Palaiologos, we follow the adventurous wanderings of an initially innocent well-off young man from Constantinople, Alexandros Favinis, from the East to the West, which start when he becomes orphan, is alienated from his relatives and is thus forced to adjust and maneuver himself out the difficulties he encounters. On the other hand, in Stratis Kalopicheiros by Stefanos Koumanoudis, a young boy from Salona leaves his birthplace and starts working as a servant. However, he constantly changes masters since he is always in trouble because he insists on behaving according to the example of holy fools, apparently for reasons of faith but, as it turns out, mostly for reasons of interest. Pope Joan, the heroine of the emblematic hybrid work by Emmanuel Rhoides, which of course defies any generic classification, doesn’t need any further recommendation. Rhoides narrates the reversed life of a sinful “saint”, who dressed like a man, manages to deceive those around her for the sake of glory and love.

How do they relate to the broader socio-political environment in which they appeared?

Putting heroes such as a servant of multiple masters or a wandering rogue in the spotlight enables writers to shed light and comment on diverse aspects of social life. In Ermilos, the allegory of a human transformed to an ass is used to highlight moral dehumanization with concrete reference to the cycle of Phanariots who held high posts and introduced disastrous, in the writer’s view, western ideas and habits. The writer satirizes different social groups such as doctors and priests, as well as specific persons, such as Dimitrios Katartzis. He delves into the political shortcomings of the Greek people during the Pre-revolutionary period and urges Greeks towards a higher moral that will enable Greece’s Renaissance. Similarly, Pitsipios parodies the apery that characterizes the Greek world after the Revolution, laying emphasis onthe attachment of Greek people to western parties, theiryearn for western education and mostly the adoption of western manners and habits.

The same goes in The Man of Many Sufferings which provides an even wider panorama due to the hero’s wanderings around the Ottoman world, the Danube countries, Russia, Western European countries and the modern Greek state. Finally, in Stratis Kalopicheiros and well as in Pope Joan, criticism is articulated against specific practices related not only to the Greek ecclesiastical and monastic life. Although Pope Joan takes place during the Medieval Years of the West, due to the writer’s famous juxtaposing similes and interventions, the interest is constantly shifted from the past to the present, offering him the chance to criticize a great number of issues related to the Greek and the European reality of the 19th century.

Which are the main challenges researchers in Greece are faced with?

With the advent of the digital era, research work has been significantly facilitated compared to twenty years ago when contemporary research tools were not available. Most Greek academic libraries have been modernized and enriched and thus constitute, together with academic research labs, incubators for university students and young scientists.

Yet, research in Greece continues to be an arduous and poorly paid, if not a self-financed occupation, especially as regards the field of Humanities, which is under attack overall. Among others, due to a short-sighted focus on “market needs”, money allotted to the respective research programs are scarce compared to other “cutting-edge” fields. Especially now after the institutional separation of Research & Technology from Higher Education, things seem to have become even more difficult.

Major difficulties are particularly faced by researchers with no stable academic working positions, although they are the ones who need research the most not only for financial reasons but also to improve their academic profile. For instance, contract teachers in the Hellenic Open University with no other main occupation are far from supported in their research work, for which they are mainly evaluated and on which their working future mostly depends. Their chances to submit or participate in the Institution’s research programs are limited, if not non-existent, while they are not financially supported in order to take part in scientific conferences etc. And of course the Hellenic Open University is just one case among so many other similar cases.

Has the relocation of the National Library of Greece at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center and its transition into a new digital era of innovation and extroversion facilitated research work?

The National Library of Greece comprises the country’s biggest research library, which houses important and quite rare material. The completion of its transfer to a new building was long awaited since researchers had no access to this material for quite some time. The excellent infrastructure of the new building together with its digital potential are undoubtedly quite conducive to the modernization of the services offered. The difference compared to the previous state of things is already more than evident.

Yet, due to its existing Regulation, the Library doesn’t seem to facilitate research to the greatest possible extent and thus satisfy its primary purpose. The pre-booking system may enable researchers to pre-order the material they are interested in, yet, in case they want to consult any additional material during their visit to the library, they cannot do so. They should pre-book anew and go to the library another day since orders cannot be carried out the same day. Most importantly, contrary to what happens in other research libraries both in Greece and abroad, researchers aren’t allowed to reproduce even one page from any journal unless 70 years have passed since the death of the respective editor and writer.

In addition, one is not allowed to make one’s own digital copies even from books or journals that do not fall within the abovementioned categories, while a researcher is allowed to do so, for instance, in the Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive (ELIA), the Library of the Hellenic Parliament and the Academic Libraries around the country. One should fill in the respect form to order copies, which, due to the increasing number of similar requests, may not be satisfied in time. I am afraid that the National Library is currently a super-modern library which, yet, rather discourages researchers and forces them to turn to other libraries in order to carry out their research. It’s more than necessary for the National Library to find as soon as possible the way to become more supportive to researchers, who have always been the main body of its users, so that its role is not in practice annulled.

It has been argued that Greek writers who live in Greece play no role in the so-called “world republic of letters”, noting that no Greek author or trend is included in textbooks and surveys of, say, Romanticism or the Avant-Garde, feminism or post colonialism, the ballad or the short story. Yet a promising development is that in recent years Greek poets and novelists have been circulating all over the world. Is there a way for the challenges of integrating Greek literature in the international field to be met?

That’s a tough question. How can a peripheral literature such as the Greek attract the attention of foreign readers in countries with diverse anthropogenic and social traits or compete with an, let’s say, Anglo-Saxon or German market? There have been Greek writers such as Emmanuel Rhoides, Konstantinos Cavafi, Nikos Kazantzakis and our Nobel laureates (Odysseus Elytis, Giorgos Seferis), who have gained some international recognition. But what about other quite remarkable modern Greek writers who don’t belong to the world literary canon, as the abovementioned writers do? As Iakovos Anyfantakis the novelist put it quite eloquently in a recent interview: “We are neither too exotic nor too global. We don’t represent something different that would entice foreign readers to explore us; nor are we international enough so that the issues we focus on are recognized beyond national borders. Τhus, even very important Greek writers, who have nothing to be jealous of its foreign counterparts, remain in the margin of world literature, lost behind the shelves of major academic libraries”. Then again, is there a recipe to be followed so that a writer can gain some kind of international recognition? I don’t think so.

Yet, no doubt a long-standing strategy on the part of the official state, as well as various initiatives by Greek and foreign institutions, among which I would include Universities, especially Universities abroad, which somehow act as cultural ambassadors, could contribute to a more effective promotion of modern Greek literature. Priority should be given to the financing and promotion of translations, along with the participation in international fora and book fairs, cooperations and further actions. This may still not be enough, yet it definitely constitutes a prerequisite.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE