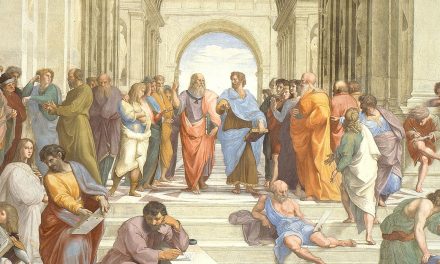

The presence of Jews in Greece traces back to ancient times. These Greek Jews, known as Romaniotes, are considered among the oldest Jewish communities in the world today. In their long history they withstood the rise and fall of many empires and thrived in their Greek homeland.

The importance of Thessaloniki for the Greek Jewish community is better understood when compared to the other Jewish communities in Greece: none had more than 2,000-3,000 members, while Jewish communities in other Ottoman cities like Istanbul (Constantinople) or Izmir (Smyrna) never rose above 5%-10% of the population.

The importance of Thessaloniki for the Greek Jewish community is better understood when compared to the other Jewish communities in Greece: none had more than 2,000-3,000 members, while Jewish communities in other Ottoman cities like Istanbul (Constantinople) or Izmir (Smyrna) never rose above 5%-10% of the population.

The author and poet Iakovos Kambanellis is a survivor of the Mauthausen concentration camp, who in the early sixties wrote “Mauthausen,” following up in 1965 with four more poems on the same topic. These were set to music my Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis in the Ballad of Mauthausen superbly sung by Greek contralto Maria Faradouri. A performance of “Mauthausen” was held at the site of the concentration camp in 1988, which was flooded by thousands of survivors and pilgrims.

The author and poet Iakovos Kambanellis is a survivor of the Mauthausen concentration camp, who in the early sixties wrote “Mauthausen,” following up in 1965 with four more poems on the same topic. These were set to music my Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis in the Ballad of Mauthausen superbly sung by Greek contralto Maria Faradouri. A performance of “Mauthausen” was held at the site of the concentration camp in 1988, which was flooded by thousands of survivors and pilgrims.

They spoke a dialect of Greek with words and phrases from Hebrew and Turkish (Judeo-Greek) and had developed their own culture and customs within the confines of the Byzantine Empire, living on the mainland as well as on some islands, like Rhodes, Chios and Samos.

However, little is known of their history and their rich tradition now stands on the verge of extinction. Thanks to Vincent Giordano’s video and photographs, we now have an insight into the rituals, customs, and traditions of the Romaniotes community in Ioannina. The Jewish population of Greece increased dramatically in 1492, after the Catholic monarchs of Spain – Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand – at the instigation of the Inquisition, issued the decree of Granada, according to which all Jews who refused to convert to Catholicism were to be expelled within 6 months; it is estimated that more than 200,000 Jews were expelled from that “cursed land.”

Thessaloniki: “Mother of Israel”

They Came from Sepharad

Following their expulsion from Spain, many Spanish Jews settled in Thessaloniki, with the largest numbers arriving in 1492-3 and 1536. Their synagogues were named after their native countries or towns. Thessaloniki also received Marranos, Jews expelled from Portugal.

The Jews from Spain and their descendants were called Sepharades or Sephardim, from the biblical Hebrew name of Spain, Sepharad. They spoke Judeo-Spanish, or as it was called Ladino, an idiom originating from the dialect spoken in Castile in the 15th century.

Thus, in the 16th-18th centuries, Thessaloniki housed one of the largest Jewish communities in the world, with a solid rabbinical tradition.

The city had become the Jewish centre of Europe, a veritable Jerusalem of the Balkans – the “city and mother of Israel,” according to Jewish poet Samuel Usque. During the 16th century, there were numerous important rabbis whose influence spread beyond the borders of the Ottoman Empire. Although Thessaloniki suffered from plagues and fires in the course of the 17th century, the city remained a centre of religious studies and Halakhah (Jewish Law), as well as an international centre of Jewish printing, as the city’s approximately 30.000 Jews constituted nearly half of its total population.

The city had become the Jewish centre of Europe, a veritable Jerusalem of the Balkans – the “city and mother of Israel,” according to Jewish poet Samuel Usque. During the 16th century, there were numerous important rabbis whose influence spread beyond the borders of the Ottoman Empire. Although Thessaloniki suffered from plagues and fires in the course of the 17th century, the city remained a centre of religious studies and Halakhah (Jewish Law), as well as an international centre of Jewish printing, as the city’s approximately 30.000 Jews constituted nearly half of its total population.

The city had become the Jewish centre of Europe, a veritable Jerusalem of the Balkans – the “city and mother of Israel,” according to Jewish poet Samuel Usque. During the 16th century, there were numerous important rabbis whose influence spread beyond the borders of the Ottoman Empire. Although Thessaloniki suffered from plagues and fires in the course of the 17th century, the city remained a centre of religious studies and Halakhah (Jewish Law), as well as an international centre of Jewish printing, as the city’s approximately 30.000 Jews constituted nearly half of its total population.

The city had become the Jewish centre of Europe, a veritable Jerusalem of the Balkans – the “city and mother of Israel,” according to Jewish poet Samuel Usque. During the 16th century, there were numerous important rabbis whose influence spread beyond the borders of the Ottoman Empire. Although Thessaloniki suffered from plagues and fires in the course of the 17th century, the city remained a centre of religious studies and Halakhah (Jewish Law), as well as an international centre of Jewish printing, as the city’s approximately 30.000 Jews constituted nearly half of its total population.A Thriving Community

The city’s Jewish element remained dominant during the first two decades of the 20th century, and Thessaloniki enjoyed unprecedented commercial development, with Jews found in every trade and profession, as traders, bankers, industrialists, teachers, physicians, lawyers, but also tobacco and port workers.

On the Sabbath, the city and its port came to a standstill, as it was observed by the Jewish community. According to a 1913 Greek government census, out of a total population of 157,889, the Jews numbered 61,439, while 49,956 were Greek Orthodox Christians and the rest Muslims.

The importance of Thessaloniki for the Greek Jewish community is better understood when compared to the other Jewish communities in Greece: none had more than 2,000-3,000 members, while Jewish communities in other Ottoman cities like Istanbul (Constantinople) or Izmir (Smyrna) never rose above 5%-10% of the population.

The importance of Thessaloniki for the Greek Jewish community is better understood when compared to the other Jewish communities in Greece: none had more than 2,000-3,000 members, while Jewish communities in other Ottoman cities like Istanbul (Constantinople) or Izmir (Smyrna) never rose above 5%-10% of the population.When the Young Turks, who revolted against Sultan Abdul Hamid II, tried to recruit all non-Muslims into the Turkish army, many young Jews left and emmigrated to the USA. At the same time, the first Zionist organizations appeared in Thessaloniki of which there were more than 20 on the eve of WW II.

After the Balkan Wars

The City Changes

Following the Balkan wars (1912-1913), the victorious Greek army entered the city on October 26, 1912, and Thessaloniki became part of the Greek state. King George of Greece declared that Jews and all other minorities were to have the same rights as the Greek population. This significant event was followed by a sequence of further developments which would lead to fundamental changes in the city’s demographic balance.

Around 40.000 Greeks (who fled the Bulgarians), and another 100,000 Greeks (expelled from eastern Thrace by the Turks) poured into the city, followed in tow by another wave of Greek refugees from Asia Minor (due to the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, under the terms of the Lausanne Treaty of 1923), the Hellenic element became dominant in the city. The Jews nevertheless maintained their influential status in the city’s economic, cultural and social development; Abraham Benaroya, for instance, became one of the founders of the Greek Labour Movement, by creating the Workers’ Solidarity Federation.

In 1917 -and five months before the Balfour Declaration- Foreign Minister Nikolaos Politis declared himself in favour of an independent state in Palestine. According to author Rena Molho’s account, the first anniversary of the Declaration the following year was celebrated by the Thessaloniki community with “a grandeur unprecedented for most Jewish communities in Europe.”

Legal Status

In 1920, the government of the liberal statesman Eleftherios Venizelos passed legislation defining the constitutional position of Greek Jewry, whereby all adult males over 21 were given the vote, the duties of the rabbinate were spelled out for the first time, etc. The Greek state supported Jewish life in many ways, e.g. Yom Kippur was made a public holiday.

Under new educational policies, the Greek language was introduced in Jewish schools, helping the younger Jewish generation learn Greek – an important factor towards social integration, without the loss of their traditions and mother tongue.

Certain events, however, like the Thessaloniki great fire of 1917 which left thousands of Jews homeless, the 1922 law which replaced the Sabbath with Sunday as the day of rest, and the anti-Semitic Camp Campbell provocative riots in 1931, caused another wave of immigration, mainly to France, but to Palestine as well.

World War II and the Shoah

Greece successfully repelled an Italian invasion through Albania in October 1940, and subsequently managed to force back the invaders deep into Albanian territory, marking the first victory against the Axis powers in Europe.

The Jewish male population served in the Greek army and fought alongside the Greeks; Colonel Mordechai Frizis (see photo) was the first high-ranking officer to fall in action. Greece, however, succumbed to the superior German forces when they invaded Greece on 6 April 1941; German troops entered Thessaloniki 3 days later.

The Trains to Poland

After a fury of anti-Jewish measures introduced by the occupying Nazis forces, the Final Solution was extended to Greece early 1943. Chief Rabbi Dr Cevi Koretz was told to prepare his flock to wear the yellow star, mark their shops, and dwell in a ghetto. The first train to Auschwitz, with 2,800 people on board, left on March 15, 1943.

According to German records, approximately 45,000 people reached Auschwitz from Thessaloniki, and only less than 5% of Thessaloniki’s Jewish population escaped deportation.

Some hundreds went underground, hiding with Christian friends; some joined the Greek Resistance, some fled to the mountains while others went to Athens; an unknown number of children were adopted by Christian families and Italian consular authorities managed to save a few hundreds, while Greek men with Jewish wives managed to save their families.

Hide Thy Neighbour

After the Italian armistice in September 1943, the Germans turned to Athens to locate and wipe out the Jews of the city. The situation there, however, was quite different, as the Jewish community was far smaller and assimilated, thus less conspicuous and easier to protect.

Archbishop Damaskinos used the clergy as a shield to protect the Jews, encouraged Christians to extend them refuge, and protested strongly to both the Greek Quisling government and German authorities.

When he visited the German military headquarters, he always carried a length of rope with him handing it to them and saying: “If you wish to hang me, as the Turks did Gregorios, here is the rope.” The Police Chief Angelos Evert issued about 18,500 false identity papers to protect all those hiding from the Germans.

Support from the Resistance was also strong. As a result, 2/3 of the Athens Jewish population was saved. In other Greek cities, local Jewish communities suffered the same fate, but to a lesser extent. At the Ionian island of Zakynthos, the decisive intervention of both the local Mayor and the local Bishop saved the day for the whole Jewish community of 275 people, a unique case in the chronicles of Europe.

According to Yad Vashem’s data- the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority established in 1953 by an act of the Israeli Knesset, 271 Greeks have been recognized as “Righteous Among the Nations.”

Aftermath

The Nazi forces finally pulled out of Thessaloniki -and eventually Greece- at the end of October 1944. Overall, out of 77,377 Jews from 27 communities around Greece, a mere 10,000 or so survived the Holocaust –a very heavy toll. Those who survived -among whom Yitzhak Persky, the father of current Israeli President Simon Peres- gradually began to return.

Those who returned to Thessaloniki, the city whose history had for centuries been so closely interwoven with their own, found their homes occupied or looted, most of their synagogues destroyed, and their old cemetery violated. Immediately after Liberation, the Greek State passed legislation for the restitution of Jewish properties to their legal owners.

Bitter memories, however, combined with harsh economic conditions in post-war Greece, made many survivors emigrate to Israel and the USA.

Today, the estimated 5,000 Jews in Greece live in 9 active communities around the country: Athens, Thessaloniki, Larissa, Chalkis, Volos, Corfu, Trikala, Ioannina, and Rhodes. In Thessaloniki, 2 synagogues are in use.

There is a Jewish Museum in Athens and a Jewish Museum in Thessaloniki. The umbrella organization of the Greek Jewry is the Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece, which was established by law in 1945, after the end of WWII.

“If we hold fast…”

In the post war period, Greek literature dealt with the life and fate of the Greek Jews, providing unique insights to the life of the community as well as individual histories.

The author and poet Iakovos Kambanellis is a survivor of the Mauthausen concentration camp, who in the early sixties wrote “Mauthausen,” following up in 1965 with four more poems on the same topic. These were set to music my Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis in the Ballad of Mauthausen superbly sung by Greek contralto Maria Faradouri. A performance of “Mauthausen” was held at the site of the concentration camp in 1988, which was flooded by thousands of survivors and pilgrims.

The author and poet Iakovos Kambanellis is a survivor of the Mauthausen concentration camp, who in the early sixties wrote “Mauthausen,” following up in 1965 with four more poems on the same topic. These were set to music my Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis in the Ballad of Mauthausen superbly sung by Greek contralto Maria Faradouri. A performance of “Mauthausen” was held at the site of the concentration camp in 1988, which was flooded by thousands of survivors and pilgrims.Greek Jews shared common historical experiences and fought on the same fronts as the majority of their Christian fellows. However, they devoutly kept up their traditions, their way of life and love of their country of origin. It is well known that the two peoples, Greeks and Jews, share a lot of common characteristics, not least their love of freedom, the arts and literature, their cosmopolitanism and their Diaspora. Winston Churchill wrote: “The Greeks rival the Jews in being the most politically minded race in the world … No other two races have set such a mark upon the world … They have survived, in spite of all that the world could do against them … No two cities have counted more with mankind than Athens and Jerusalem..”

Bibliography:

1. Documents on the History of the Greek Jews, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Greece, Kastaniotis Editions, Athens, 1999.

2. Friedlander, Saul, The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2007.

3. Kitroeff, Alexandros, “The Jews in Greece: 1941-1944: Eye-witness accounts,” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora, XII: (Fall 1985).

4. Kitroeff, Alexandros, “The Jews of Modern Greece: A bibliography” in Modern Greek Society: A social Science Newsletter, vol. 14. December 1986

5. Mazower, Mark, Salonica: City of Ghosts-Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950, Harper Collins, 2004

6. Michael Molho and Joseph Nehama, In Memoriam. The destruction of the Jews in Salonika, vol. 6&7, Thessaloniki 1978

7. Molho, Rena, The Jews of Thessaloniki 1856-1919, Themelio, Athens, 2006 (in Greek)

8. Molho, Michael, In Memoriam. Homage aux victimes Juives des Nazis en Grèce, Communauté Israélite de Thessalonique, Thessaloniki, 1973Nehama, Joseph, Histoire des Israelites de Salonique, 7 volumes, Commmunaute Israelite de Thessalonique, Thessaloniki, 1978

9. Michael Molho and Joseph Nehama, In Memoriam. The destruction of the Jews in Salonika, vol. 6&7, Thessaloniki 1978

10. Nehama, Joseph, Histoire des Israelites de Salonique, 7 volumes, Commmunaute Israelite de Thessalonique, Thessaloniki, 1978

11. Scianky, Leon, Farewell to Salonica: a world of Sephardic Jews, Greek Orthodox, and Turkish Muslims in the early 1900s, Paul Dry Books, Pennsylvania, 2003

12. Souvenir, Images of the Jewish Community, Salonika 1897-1917 (In English and Greek), Editions KAPON, Athens 1993

13. Stavrianos, L.S, “The Jews of Greece,” Journal of the Central European Affairs, vol. 8 (1948-1949).

14. Synchrona Themata, Jews in Greece, vol. 52-53, July-August 1994 (in Greek).

15. Errika Kounio – Amarilio, Albertos Nar, Oral Testimonies of Thessaloniki Jews on the Holocaust, Paratiritis, Thessaloniki, 1998 (in Greek).

16. Giorgos Anastasiadis, Leon Nar, Christos Raptis, I, the grandson of a Greek, Kastanotis, Athens, 2007 (in Greek). A book tracing the roots of the French President Nocolas Sarkozy. & European Jewish Press: Sarkozy-My Roots are in Salonica

17. Fleming, K.E, Greece: A Jewish History, Princeton University Press, 2010

See also: ERT-Archives: Documentary –Testimonies: Persecution of Jews in Occupied Greece & Jewish Holocaust [VIDEO-in Greek)