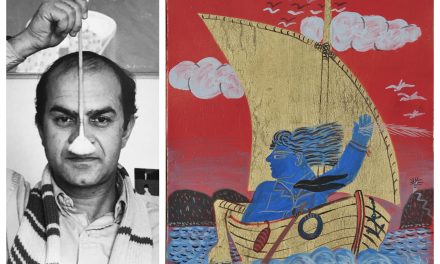

Fotis Kontoglou (1895-1965) -the greatest icon painter of modern Greece and one of the most important theologians and literary writers- was born on November 8, 1895, in the town of Kydonies (also known as Aivali) on the Aegean coast of Asia Minor, just across from the island of Lesvos. To mark the 125th anniversary of his birth, Greek News Agenda takes a closer look at the artist’s background and greatest achievements.

Kontoglou came from a devout family. Having lost his father at an early age, he kept his mother’s surname instead of his paternal Apostollelis. Many of his ancestors were monks, and his uncle, Stephanos Kontoglou, who was abbot of the St Paraskevi Monastery near Kydonies, played a significant role in Kontoglou’s life; in his book “Vasanta”, Kontoglou dedicates the chapter of translations from the Psalms of David “to the austere soul of the Hieromonk Stephanos Kontoglou, his uncle, whose virtue he perpetually had before him as a model and rule”.

In 1913, Kontoglou entered the third year of the Athens School of Fine Arts; shortly after, he decided to spend several years in Europe, especially in Paris, France (1919), where he continued his Art Studies, wrote the book “Pedro Cazas” and started gaining attention for both his paintings and writings. He returned to his homeland after the Asia Minor disaster, which had a tremendous effect on him, separating him radically from the West, on the one hand, and, on the other, making him feel responsible for the continuation, even in another space, of the long-lived tradition which had withstood the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire.

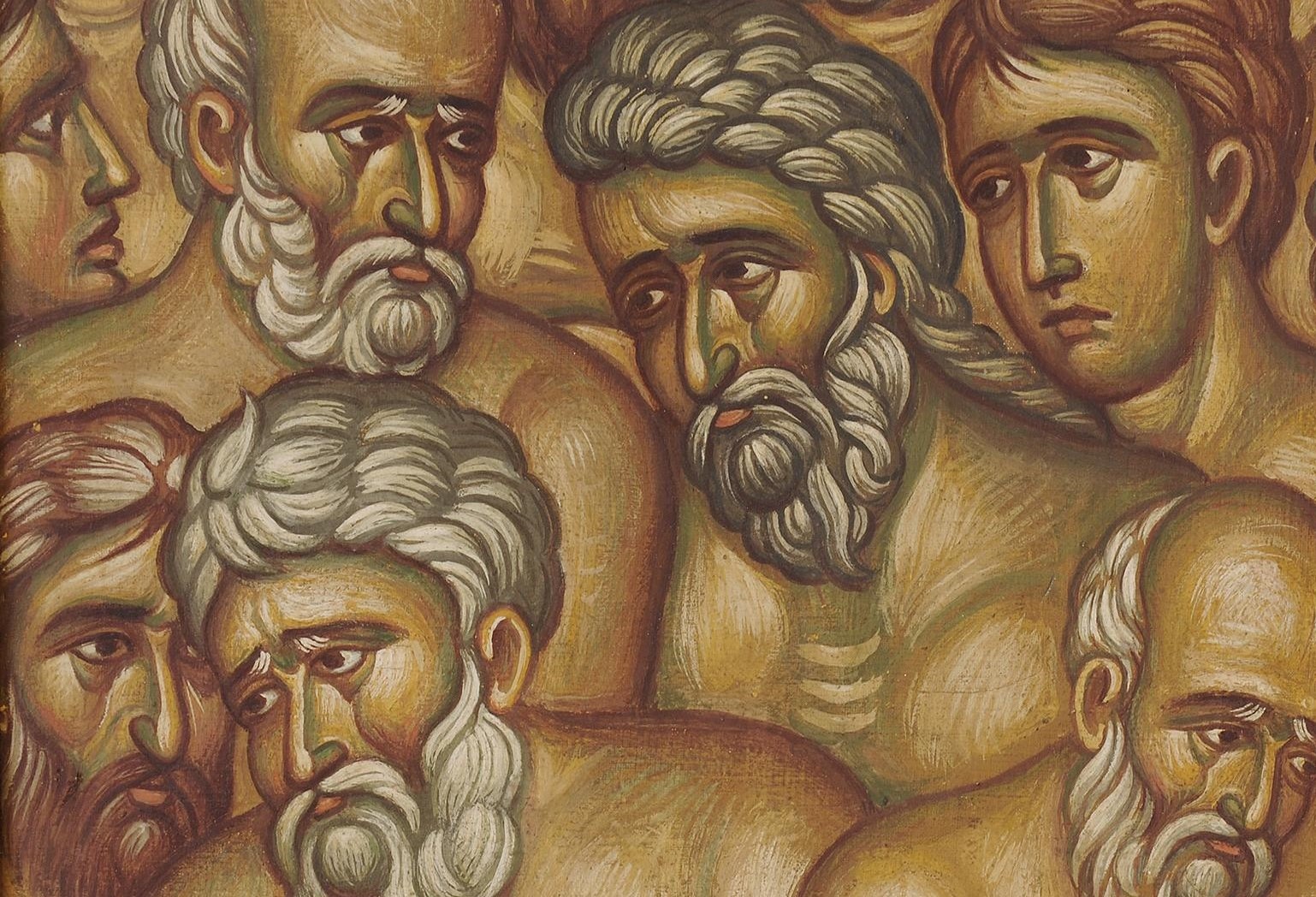

Kontoglou visited Mt Athos in 1923 where he studied the Byzantine hagiography, which became the dominating characteristic of his painting. In this journey, he came into more direct and substantial contact with ecclesiastical painting and mainly with the post – Byzantine art of the Cretan School. It is important to note where Kontoglou was taught Byzantine art, because it interprets the subsequent course of his hagiographic art. More specifically, Kontoglou dared ignored the iconography’s “classical” manner.

Kontoglou visited Mt Athos in 1923 where he studied the Byzantine hagiography, which became the dominating characteristic of his painting. In this journey, he came into more direct and substantial contact with ecclesiastical painting and mainly with the post – Byzantine art of the Cretan School. It is important to note where Kontoglou was taught Byzantine art, because it interprets the subsequent course of his hagiographic art. More specifically, Kontoglou dared ignored the iconography’s “classical” manner.

He chose the language of Byzantine Painting, which, in some cases, enriched with the knowledge of anatomy and the plastic depiction of figures. In a variety of ways, therefore, while Kontoglou adopted these techniques and styles of the past, he was at the same time approaching the modern aesthetic ideas (Expressionism, Fauvism, Surrealism) that were shaking conventional academic standards and realism, and in this respect it is possible to see his sojourn in Paris as formative. Thus, this “Easterner” who lived in Paris for some time became a source of influence and inspiration for many Greek artists of the so-called 30s Generation and their quest for “Greekness”.

“Today, after so many years, I still declare that Kontoglou’s work, in all its diverse entirety, has been of immense importance for our generation: it is one of those few creations to have enabled the forgotten voice of the east once more to be heard as it truly deserves, and to remind us of what may be the proper place for a culture destined by its own tradition to stand sovereign between the two great currents that passed across it; to weigh them, to judge them, to retain whatever of them was best, to digest them, and finally – having added a precious part of itself – to return them in a unique and incomparable synthesis.”

Odysseus Elytis, in Photis Kontoglou (Athens: Akritas Editions, 1995)

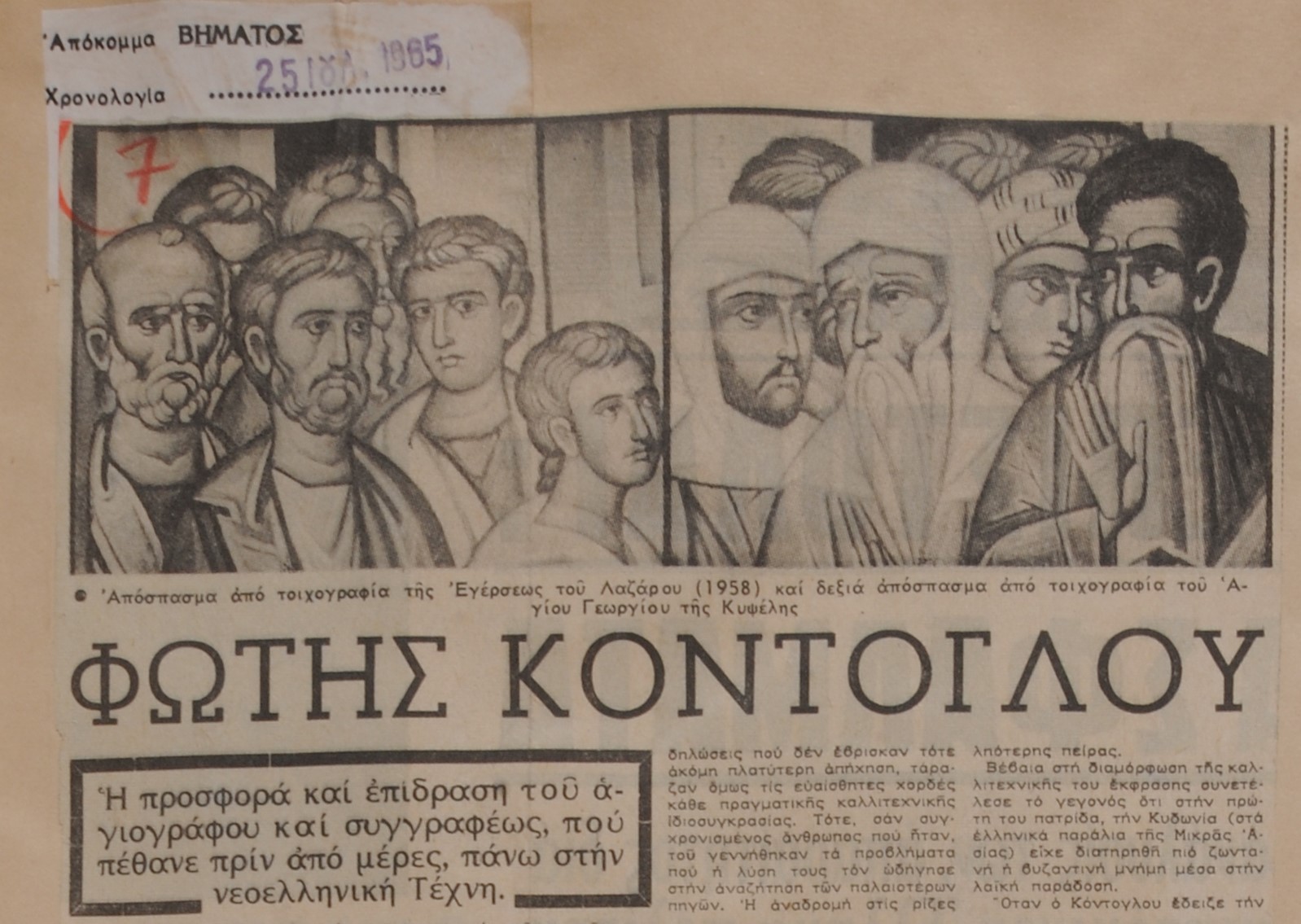

Kontoglou also worked as a preservationist for the Byzantine Museum of Athens, the Coptic Museum of Cairo, the Corfu Museum and the Peribleptos Monastery in Mystras. In 1932, with the assistance of the artists Yannis Tsarouchis and Nikos Engonopoulos, Kontoglou painted frescoes in his house; these frescoes can nowadays be found at the National Art Gallery-Alexandros Soutzos Museum. Moreover, he decorated three large rooms of the Athens City Hall with historical frescoes; this was his first large scale work as a fresco painter, and his only extensive secular one. He also took part in Panhellenies exhibitions (1938, 1948 and 1957), the Venice Biennial (1934), and the Alexandria Biennial (1957). Last but not least, he painted a large number of icons and numerous churches, both in Greece (e.g. Kapnikarea church in Athens) and the US. Through these works, Kontoglou succeeded in making Byzantine Art prevail in Greece.

Kontoglou also worked as a preservationist for the Byzantine Museum of Athens, the Coptic Museum of Cairo, the Corfu Museum and the Peribleptos Monastery in Mystras. In 1932, with the assistance of the artists Yannis Tsarouchis and Nikos Engonopoulos, Kontoglou painted frescoes in his house; these frescoes can nowadays be found at the National Art Gallery-Alexandros Soutzos Museum. Moreover, he decorated three large rooms of the Athens City Hall with historical frescoes; this was his first large scale work as a fresco painter, and his only extensive secular one. He also took part in Panhellenies exhibitions (1938, 1948 and 1957), the Venice Biennial (1934), and the Alexandria Biennial (1957). Last but not least, he painted a large number of icons and numerous churches, both in Greece (e.g. Kapnikarea church in Athens) and the US. Through these works, Kontoglou succeeded in making Byzantine Art prevail in Greece.

Overall, as Nikos Zias (archaeologist and Emeritus Professor of Art History) has pointed out, Kontoglou’s diverse contribution to Modern Greek Painting could be summarized into three manifestations. His creative painting work, which was based on the Byzantine technique; his hagiographic work, which brought orthodox painting back to Greece’s churches; and, finally, his teaching, either directly or -mainly – indirectly, which was one of the strongest factors which altered the course of Modern Greek Painting towards the discovery of the pictorial but, also, of the more substantial spiritual values of the Greek tradition.

Kontoglou died in Athens on July 13, 1965 due to surgery complications caused by a car accident. His death was deeply mourned throughout Greece. Employing Byzantine and folk painting as the guiding forces of his art, as well as studying the creations of older periods, such as the portraits of Fayum, he proved with his work to be a firm supporter of the demand for the authenticity of Greek expression, while his contribution to the fashioning of modern ecclesiastical painting is considered definitive.

Kontoglou died in Athens on July 13, 1965 due to surgery complications caused by a car accident. His death was deeply mourned throughout Greece. Employing Byzantine and folk painting as the guiding forces of his art, as well as studying the creations of older periods, such as the portraits of Fayum, he proved with his work to be a firm supporter of the demand for the authenticity of Greek expression, while his contribution to the fashioning of modern ecclesiastical painting is considered definitive.

See also on Greek News Agenda: Fotis Kontoglou: From “LOGOS” to “EKPHRASIS” and Art historian Alexandra Kouroutaki on Nativity in 20th-century hagiography in Chania.

E.S.

TAGS: ARTS | FESTIVALS | GLOBAL GREEKS | HERITAGE | HISTORY | LITERATURE & BOOKS