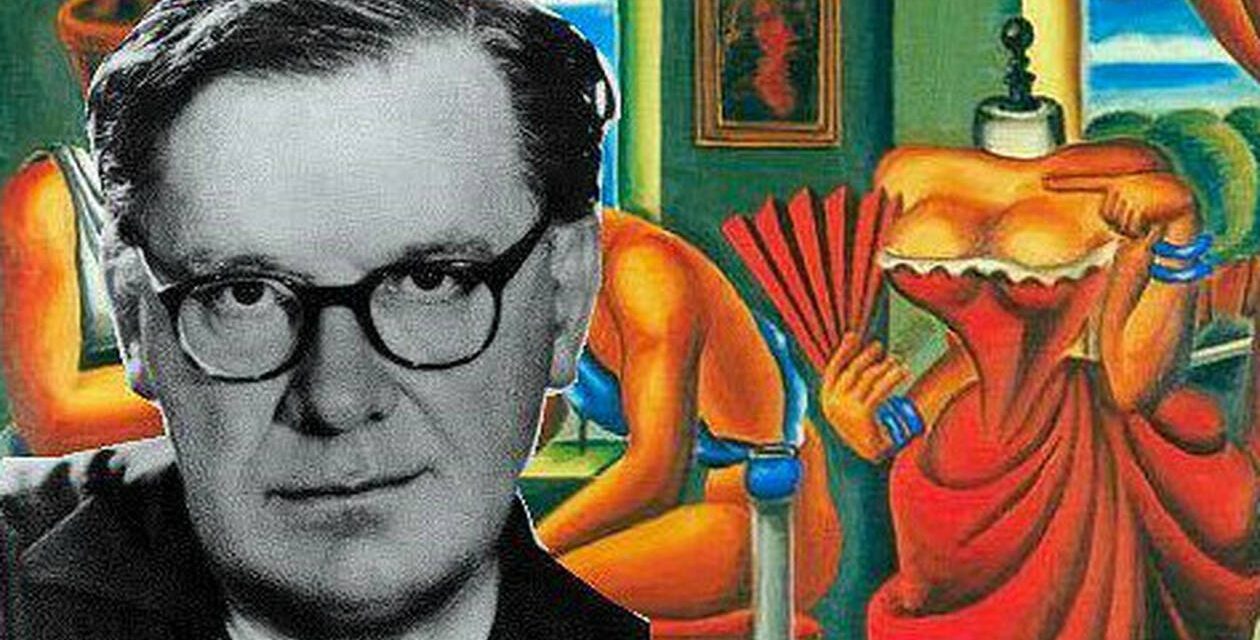

Nikos Engonopoulos (1907–1985) was one of the most prominent representatives of Greek Surrealist poetry and painting. Closely associated with Andreas Embeirikos, the “patriarch” of Surrealism in Greece, and with Nicolas Calas, an influential figure of the European and American avant-garde, Engonopoulos developed highly experimental pictorial and poetic aesthetics. To use Kimon Friar’s words, whereas “surrealism in the early Embeirikos was almost clinical, liberating, didactic, in Engonopoulos’ two first books, Do Not Disturb the Driver (1938) and The Clavicembalos of Silence (1939), it was explosive, daring and revolutionary…”.

In both his paintings and poems, he engaged in a critical, often ironic dialogue with Greek history and cultural traditions and their ideological appropriations in established cultural and political discourses. Engonopoulos was arguably the keenest advocate of Surrealist black humor and irony in Greece. His overall approach to the Greek past, informed as it was by the socio-aesthetic principles of French Surrealism, constitutes one of the most ingenious and provocative cases of artistic mythogenesis in the European avant-garde.

ON AT THE HEAD OF THEM AGAINST THE BARBARIANS

The fitting words are great and free and brave and strong,

For them, the total subjection of every element, silence, for

them tears, for them beacons, and olive branches, and

the lanterns

That bob up and down with the swaying of the ships and scrawl

on the harbours’ dark horizons,

For them are the empty barrels piled up in the narrowest lane,

again of the harbor,

For them the coils of white rope, the chains, the anchors, the

other manometers,

Amidst the irritating smell of petroleum,

That they might fit out a ship, put to sea and depart,

Like a tram setting off, empty and ablaze with light, in the

nocturnal serenity of the gardens,

With one purpose behind the voyage: ad astra.

For them I’ll speak fine words, dictated to me by Inspiration’s

Muse,

As she nestled deep in my mind full of emotion

For the figures, austere and magnificent, of Odysseus

Androutsos and Simon Bolivár.

His long poem Bolivár was written in the winter of 1942–1943 and originally circulated in manuscript form and was read at Resistance gatherings. It soon acquired the status of an emblematic act of resistance against the Nazis and their allies (Italians and Bulgarians), who had occupied Greece in 1941. It was first published by Ikaros in September 1944. The poem was also released in the form of a song, in 1968, with music composed by Nikos Mamangakis.

To use Haris Vlavianos words, “Bolivar is not only the well-known South American hero and liberator, but also, as the work carries the subtitle A Greek Poem, all Greek great and lesser heroes of the Greek War of Independence and of the Resistance and, in the final analysis, is Engonopoulos himself, for the poet declares with pride in the poem that he is his son”. As Roderick Beaton notes, “by drawing on parallels between the South American revolutions of the 19th century and recent Greek history, topical allusions are displaced under a thin disguise”. The attempt in this long poem to unite the aspirations of a Latin American (turned Greek) hero-saviour with the broader quest of the Surrealists for freedom in a universal sense produced one of the major works in the history of Modern Greek poetry.

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS