Dr Angeliki Dimitriadi, Research Fellow at the Hellenic Foundation for European & Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) and Visiting Fellow at the ECFR Berlin Office since November 2015, spoke to Greek News Agenda (GNA)* and shared her views on how Greece, Germany and EU are handling the refugee and migrant issue. Dr Dimitriadi, whose research focuses on the management of irregular migration, commented on Turkey’s role, burden sharing between EU member states and third countries, as well as possible ways forward to manage the situation.

Q: How do you think Greece has handled the migrant and refugee issue so far? What could the Greek authorities have done more and what may be done now to better manage the situation?

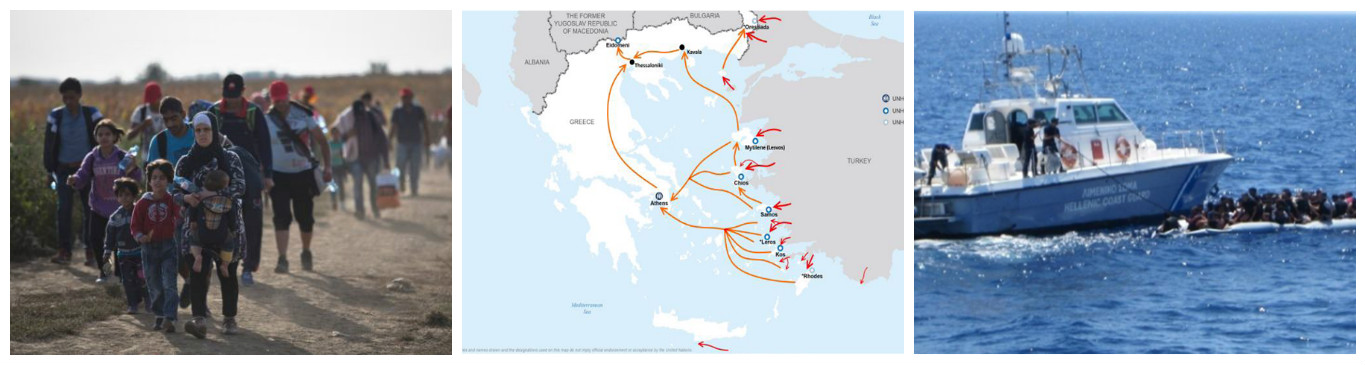

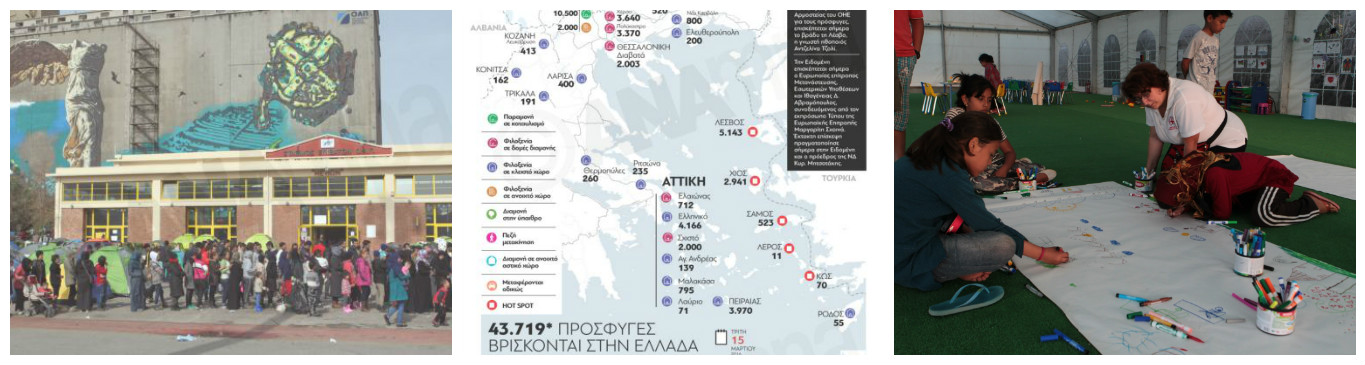

A: I think the Greek state responded with significant delays, was mostly absent in the first months of 2015 and late in addressing the situation on the ground. But its European partners were also late in assisting a country that is in a particularly vulnerable position due to the economic crisis. The hotspots should have been in place since September- they were part of the European Agenda on Migration and are important in terms of screening and registering arrivals. It took too long to set up reception places and still a significant number of arrivals primarily of non-critical nationalities (Pakistanis, Afghans etc) are outside the scope of the reception facilities. Even if they will be returned they still need to be housed and cared for temporarily while under Greek jurisdiction in humane conditions with respect and dignity.

On the other hand, the search and rescue operations of the Hellenic Coastguard have been admirable and the efforts by some NGOs as well. Civil society carried and continues to carry the burden of response on the ground. The response has been impressive but for me it is also slightly problematic. Civil society replaces state mechanisms because the latter are either absent or ineffective. As a result no one fulfils their expected role. The state and civil society should be working together and in parallel but not replacing each other. Which is why from the beginning an independent authority should have been put in place coordinating NGOs, volunteers, ministries and agencies but also municipalities. This is apparently something that will now happen and is a welcomed move. The reality on the ground is that there are a million different needs from area to area and nationality to nationality and what we need is an organized structure that functions like an umbrella- and is able to pin point at any given time what the needs are, be able to allocate funds, material and personnel.

Q: What is your view on EU’s handling of the refugee crisis, especially in view of the relocation system and the creation of hotspots in Greece? Does this solution ensure the sustainability of efforts needed to deal with the migrant flows?

Q: What is your view on EU’s handling of the refugee crisis, especially in view of the relocation system and the creation of hotspots in Greece? Does this solution ensure the sustainability of efforts needed to deal with the migrant flows?

A: The EU’s response has been fragmented. The Syrian conflict is entering its sixth year, which means we are five years late in preparing adequate response and burden sharing mechanisms to deal with arrivals we knew would eventually reach Europe. Absence of a solid and united response resulted in what we are seeing today; ‘coalitions of the willing’ but also ‘coalitions of the unwilling’. On the other hand this is not entirely surprising; The EU has a tendency to react fairly late to crises.

The hotspots are in the right direction- we need to know who enters the country and especially so when we are dealing with vulnerable populations, so that we can also ensure their protection. Relocation is more complex. The number agreed upon is realistically very small however; if the process worked it would have established a positive precedent of burden sharing in the EU. The failure of relocation in my view has to do with the fact that no wide political consensus was reached prior to the Commission’s proposal. It is emblematic of a wider problem at present in the Union; member states may commit but there is no mechanism in place that can ensure they implement their commitment. Additionally no alternatives were offered to those members unwilling to relocate refugees and by alternatives I refer to other means of contributing, perhaps more money, perhaps more specialized personnel in critical areas, equipment etc..

However relocation is only one measure and it was never designed to address the full scale of the migratory flows. The situation at present is much more complex within and outside Europe and will require a multi-pronged strategy to address the needs.

Q: What role could Germany play in the progress of the relocation system, and more generally for a fairer burden sharing between EU member states?

A: Germany has tried to lead extensively and it has also tried to assist Greece. The Chancellor remains the staunchest supporter of relocation and burden sharing. However, the recent results in the three state elections in Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate and Saxony-Anhalt are a reflection of the pressure Chancellor Merkel is under but also the increased division within Germany as regards the refugee policy. There is a gradual acknowledgement that relocation, as originally proposed, is not working. Hence the shift of focus to Turkey and the EU-Turkey deal as a last solution to address incoming numbers. This does not mean that Germany will not continue to assist or seek a European response but it will require allies and more importantly it will need to be able to point to progress on the ground.

I am not sure there is fertile ground at present for a fairer burden sharing between EU member states. At best we may hope for coalitions of the willing, to split tasks and responsibilities though in the long term that’s unsustainable. It is very difficult to achieve political agreements during a period of crisis and where events progress quicker than policy.

Q: How do you comment on recent discussions in certain circles in Europe regarding the Schengen zone, increasing border restrictions and imposing a cap on asylum applications? Could they possibly reflect a potential political rift within the EU?

A: This is not the first time Schengen is brought up following a migration ‘crisis’. We should not forget that after events of 2011 in Lampedusa at the height of the Arab Spring and following the Franco-Italian rift over the border crossing of Tunisians, EU leaders amended the Schengen code to include the re-imposition of internal border controls as regards a Member State, if there are persistent serious difficulties or deficiencies detected in that Member State’s control of external borders. At present the impression in Europe is that Greece cannot protect its borders. Realistically, there is very little one can do on the maritime border. The legal framework in place (and correctly so) prohibits push backs and requires rescue and safe disembarkation. The land border is a different issue and there I do think there were alternative ways for Greece to negotiate the wave through of the refugees to other countries. Obviously Greece could not and does not have the capacity to keep almost 1 million refugees in the country but a more organized and methodical manner of border crossing would have helped, regulated from the Greek side to avoid this impression of utter chaos. As things stand today, the discussion on Schengen and Greek membership hurts Greece at a political level. I agree that border restrictions and the asylum caps demonstrate a political rift in the Union but for me the question is between which countries. Irrespective of what is being said and done, the Visegrad states need Germany, the western Balkans traditionally look to Austria and Germany. The danger is that the inability to manage the refugee flows will isolate Greece further and that will have broader geopolitical and strategic implications for a country already fragile and already carrying a significant burden.

Q: How significant is EU’s and Greece’s cooperation with Turkey on the issue?

Q: How significant is EU’s and Greece’s cooperation with Turkey on the issue?

A: Turkey is a crucial partners in this by virtue of its geography. However, Turkey has showcased a remarkable ability to instrumentalise migration, i.e. it is using the issue of refugee and migrant flows to further its own political and strategic agenda. Thus, any cooperation should be treated with caution because for Turkey the Syrian refugees are a small part of a much broader issue as regards Syria and Turkey’s role in the region. We need cooperation but on equal terms and with respect to human rights. Greece also needs to carefully walk the line between cooperating and safeguarding its own national interests.

Q: What scenarios do you see unfolding for the refugee issue in the future? What could be a realistic way forward?

A: At present there are various potential ‘hot spots’ that can produce significant numbers of refugees, including Yemen, the Lake Chad region, and of course Afghanistan remains a source country. We will have to talk about legal means of entry especially for asylum seeking populations directly from third countries and reach a consensus and a way forward. It is unrealistic for Europe to expect third countries alone will carry the burden. It is also imperative to strengthen Jordan and Lebanon to continue hosting the refugee populations and improve living conditions. We also will need to discuss openly integration in Europe and address the present gap in integration capacity member states have. And we need to move beyond crisis-mode. The numbers that reached Europe since 2015 are undoubtedly significant and at times appear overwhelming but this is because we failed to cooperate with each other. 1 million people in a Union of 500 million inhabitants do not make a crisis.

On Greece I think the immediate concern should be to strengthen the Asylum Service, particularly first instance to avoid any potential back log. As regards the way forward Greece by virtue of its geography will always function as an entry point. This means that Greece has to develop a coherent asylum system that moves beyond protection and is linked with integration, offers assistance to those who receive protection until they can become self-sustained, create reception facilities and a humane return program. All the above require financial investment which Greece does not have. However it is an area where the Commission has expressed willingness to assist. Realistically all member states will have to realise that in one way or another they will have to undertake some form of burden sharing and that in the case of Greece a portion at least of those who arrive will have to stay in the country. But this can also be a huge opportunity and resource for the country if addressed correctly early on.

Angeliki Dimitriadi earned a PhD in Social Administration with a focus on irregular migration from Democritus University in Greece, a MA in War Studies from King’s College London & a BSc in International Relations & History from the LSE. Her areas of expertise are: Irregular migration, asylum, securitization of migration, Common European Asylum System, Afghanistan and Greece. She is also co-Investigator to the ESRC Urgent Research Grant (University of Warwick and ELIAMEP), entitled ‘Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by boat: Mapping and documenting migratory journeys and experiences’, monitoring current refugee flows and is working on a monograph on the governance of irregular migration at the borders of the European Union, to be published by Routledge in late 2016.

* Interview by Eleftheria Spiliotakopoulou (& Ioulia Livaditi)

More @ Greek News Agenda: ELIAMEP Think Tank: Analyzing the Refugee Crisis, Opinion: Global Cooperation Key for Refugee Crisis, Opinion: No Scapegoating in a Real EU policy for the Refugee Crisis; Fact sheet: Greece Dealing with the Refugee Crisis

TAGS: GLOBAL GREEKS | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | MIGRATION | REFUGEE CRISIS