A large number of festival were held in Athens throughout the year, usually in honour of Gods, such as Dionysus, Apollo, Hermes and, of course, Athena, the city-state protectress, while others were centred around concepts such as family or citizenship. Several of them were of great ancientness while others did not emerge until the 5th century BC. In this article, we present some of the most prominent festivals that took place in the city of Athens and the widest region of Attica, without excluding those that were also observed in other parts of Greece.

Dionysia

Although the name is often used to collectively refer to four distinct festivals dedicated to the god Dionysus, taking place in different times of the year, it is most closely associated with the largest and most famous festival associated with the Dionysiac cult, the “City Dionysia”, also known as the Great Dionysia, which took place in springtime.

The most ancient one of these festivals is however believed to be the “Rural Dionysia” which was held in the Attic month of Poseideōn, corresponding to the second half of December and first half of January, and thus straddling the winter solstice. The festival celebrated the cultivation of vines, and included offerings of bread and fruit, phallic processions, wine-drinking, singing and dancing. Because the various towns in Attica held their festivals on different days, it was possible for spectators to visit more than one festival per season.

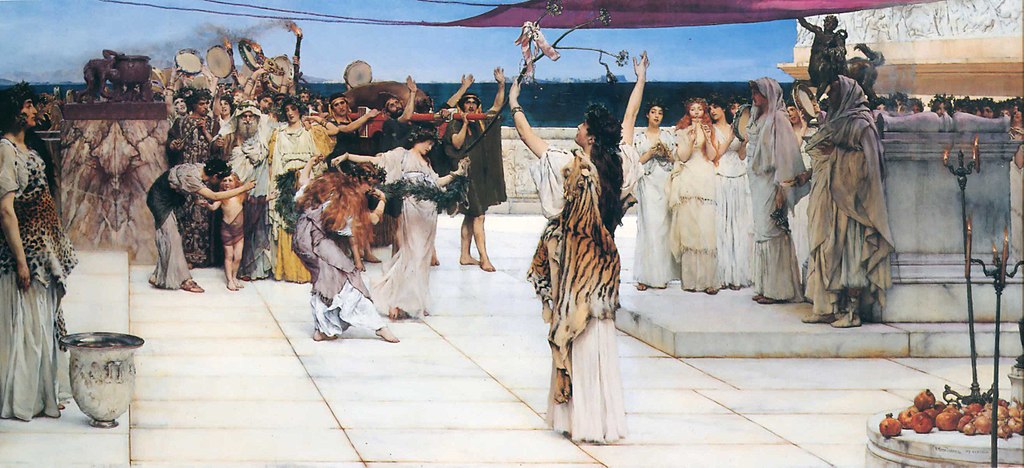

A dedication to Bacchus, 1889, Lawrence Alma Tadema (by artrenewal via Wikimedia Commons)

A dedication to Bacchus, 1889, Lawrence Alma Tadema (by artrenewal via Wikimedia Commons)

The City Dionysia (Dionysia ta en Astei) or Great Dionysia was the urban part of the festival, possibly established during the tyranny of Peisistratus in the 6th century BC. This festival was held probably from the 10th to the 16th of the month Elapheboliōn (the lunar month straddling the vernal equinox, i.e., Mar.-Apr in the solar calendar), three months after the rural Dionysia, probably to celebrate the end of winter and the harvesting of the year’s crops.

The City Dionysia began with a procession, in which citizens, metics, and representatives from Athenian colonies marched to the Theatre of Dionysus on the southern slope of the Acropolis, carrying the wooden statue of Dionysus Eleuthereus along with phallic symbols; also included in the procession were bulls to be sacrificed in the theatre. That was followed by dithyrambic competitions, animal sacrifices and a large feast. During the next days, a theatrical of great importance contest took place at the Theatre of Dionysus; most of the extant Greek tragedies, including those of Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles, were for the first time performed there. Another procession and celebration was held on the final day, when the judges chose the winners of the tragedy and comedy performances. The winning playwrights were awarded a wreath of ivy.

Between the Rural and City Dionysia, other two lesser festivals took place in honour of Dionysus: The Lenaia and the Anthesteria. The first took place in Athens in Gameliōn, roughly corresponding to January, while the latter was held each year from the 11th to the 13th of the month of Anthesteriōn, which was named after the festival.

The Lenaia was mostly an agrarian festival, believed to have included a procession, chanting, sacrifices, nocturnal rites and, possibly, special rituals for women. Beginning in the second half of the 5th century BCE, plays were performed, as in the City Dionysia, and awards were given, initially only for comedies, and later also for tragedies.

Maenads in ecstatic dance around the cult image of Dionysos at the Lenaia, attic red figure cup type B, ca. 490-480 BC (by ArchaiOptix via Wikimedia Commons)

Maenads in ecstatic dance around the cult image of Dionysos at the Lenaia, attic red figure cup type B, ca. 490-480 BC (by ArchaiOptix via Wikimedia Commons)

The Anthesteria were held for three days; the first one was called Pithoigia (“Jar Opening”), where libations were offered to Dionysus from the newly opened casks; the second one, called Choes (“Wine Jugs”), included wine-drinking contests while on the third day –Chytroi (“Pots”)– pots of seed or bran were offered to honour the dead.

Thargelia

The Thargelia was one of the chief Athenian festivals in honour of the Delian Apollo and his sister Artemis, held on their supposed birthdays, on the 6th and 7th day of the month Thargeliōn (corresponding to 24 and 25 May). Basically a vegetation ritual onto which an expiatory rite was grafted, the festival was named after the first fruits, or the first bread from the new wheat. It is said to have initially featured the sacrifice of two Pharmakoi, men chosen among slaves or a criminals; it is not certain whether these men were actually executed, or ridiculed and beaten. It has been suggested that the human sacrifices of more ancient times were later replaced by a milder form of expiation.

Skirophoria

The Athenian festival of Skirophoria or Skira was celebrated annually at threshing time on the 12th of Skirophoriōn (June/July), which was named after it. It was linked with human and agricultural fertility, and only women were allowed to participate. A solemn procession was held from Athens to a sanctuary of Athena in the site of Skiron near Eleusis, led by the priestess of Athena and the priests of Poseidon and Helios (sun god), under the cover of a white ceremonial canopy. No sources survive describing the nature of the rituals that took place at the temple.

Phryne at the Poseidonia in Eleusis, Heinrich Semiradsky (State Russian Museum via Wikimedia Commons)

Phryne at the Poseidonia in Eleusis, Heinrich Semiradsky (State Russian Museum via Wikimedia Commons)

Panathenaea

The Panathenaea (now often referred to as the Panathenaic Festival) was the most important festival for Athens and one of the grandest in the entire ancient Greek world, and took place every four years with great splendour. They were held in honour of Athena, the patron goddess of the city-state (Athena Polias). Their status in Attica was only surpassed by that of the Olympic Games, and representatives of all the dependencies of Athens were present, bringing sacrificial animals.

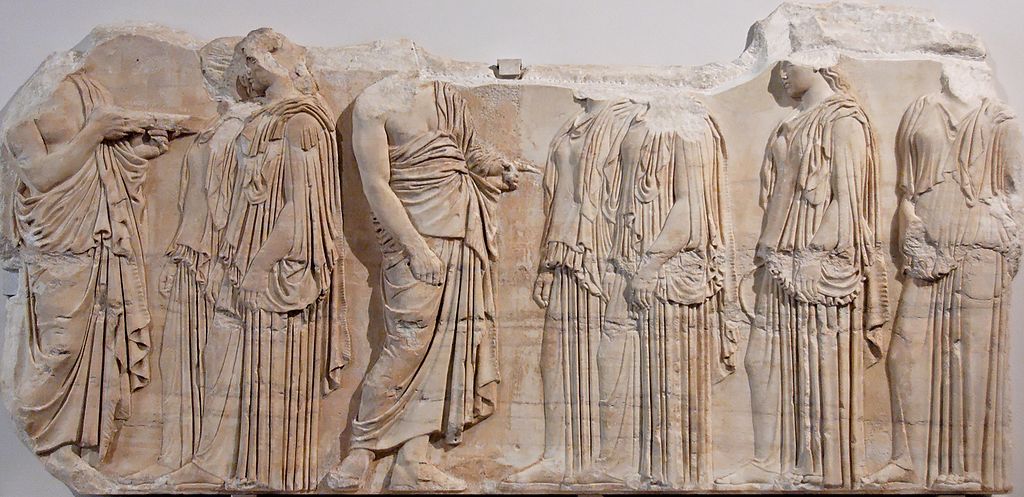

Panathenaea was celebrated at the end of the Attic month of Hekatombaiōn, roughly corresponding to mid-August, and consisted of the sacrifices and rites proper to the season. The religious festival began with a great procession, which started from a double-arched gate in the city’s fortifications called Dipylon (double gate), in the area of Kerameikos, and moved along the large road known as the Panathenaic Road. The procession (which is the subject of the famous frieze of the Parthenon) was led by led by girls of noble origin carrying a veil they had weaved, embroidered with scenes from the Gigantomachy. When they reached Athena’s temple on the Acropolis, they laid the veil on her statue.

Ergastinai (“weavers”) block, from the east frieze of the Parthenon, Athens, c. 445–435 BC (by Jastrow via Wikimedia Commons)

Ergastinai (“weavers”) block, from the east frieze of the Parthenon, Athens, c. 445–435 BC (by Jastrow via Wikimedia Commons)

The festivities also included a hecatomb and other sacrifices to Athena but also other gods and were followed by the Panathenaic Games, which comprised of sports and musical contests, with different categories for young boys and men. The athletic competitions are believed to have included equestrian games and sports like stadion (running race), wrestling, boxing, pentathlon, pankration (a mixed martial art) and others, while the musical contest included rhapsodic recitation of Homeric poetry, singing and instrument playing. The victors were given Panathenaic amphorae (large ceramic vessels containing olive oil) as prizes.

The musical contests were held at the Odeon of Athens, built by Pericles in 435 BC, while the athletic competitions were staged at the Panathenaic Stadium (still in use today, following excavations and remodelations) since its construction by the Lykourgos, c.330 BC.

The Lesser Panathenaea was a similar festival with a more local character, believed to have been celebrated annually. Their duration was shorter by 3 to 4 days compared to their more illustrious counterpart, and only Athenians could participate.

Kronia

The ancient Athenian festival of Kronia used to take place on the 12th day of Hekatombaiōn, in honour of the father god Kronos (Cronus), considered a patron of the harvest. It was a public holiday which only lasted one day, but was even observed by the slaves, who would sit on the same table as their masters to enjoy the fruit of their hard labour. It also included offerings, especially of fruit and bread. Although it was celebrated in the summer, it was a major influence on the most popular Roman festival, the famous Saturnalia, dedicated to Saturn, Cronus’s Roman equivalent.

The Gardens of Adonis, 1888, John Reinhard Weguelin (via Wikimedia Commons)

The Gardens of Adonis, 1888, John Reinhard Weguelin (via Wikimedia Commons)

Adonia

The festival of Adonia was held annually in honour of Adonis, consort of Aphrodite, who personified the rebirth of nature. Their date is uncertain and may have varied, as did their duration, but it was most probably a spring or summer festival, and was not officially organised. It was observed by women in most parts of Greece, but is best attested in classical Athens. Over it course of the festival, Athenian women took to the rooftops of their houses and ritually mourned the death of Adonis through song and dance. They planted lettuce and fennel seeds in potsherds, creating the so-called “Gardens of Adonis”, which sprouted before withering and dying. The women would then conduct a mock funeral procession carrying the “Gardens” and small images of Adonis, before ritually casting them into the sea or in springs.

Boedromia

The Boedromia was a lesser festival dedicated to of Apollo Boedromios (the helper in distress – literally, “racing to aid in response to a cry for help”). It was an exclusively Athenian festival, taking place in the month of Boedromiōn, which was named after it, at a time corresponding to mid-September. It apparently had a military aspect, as the Athenians thank the god for what they perceived as his divine assistance in battle.

Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries were the most famous secret religious rites of ancient Greece. They were initiations for the cult of Demeter, goddess of agriculture, and her daughter Persephone (who, like Adonis, personified the rebirth of nature), held annually in Boedromiōn and lasting about nine days. Its origins are believed date back to the Bronze Age; it was a major festival throughout the Classical and Hellenistic era, and later spread to Rome. As in the Thesmophoria, Persephone’s myth was honoured for symbolising the perpetual cycle of life.

The mysteries represented the myth of the abduction of Persephone by Hades (the god of the underworld) in a cycle with three phases: the descent into the underworld, Demeter’s search, and the ascent – with the main theme being the ascent of Persephone and the reunion with her mother. The rites and beliefs were kept secret from the outsiders, and the sites of the ceremonies were strictly forbidden to the non-initiated.

Thesmophoria, 1894-1897, Francis Davis Millet (via Wikimedia Commons)

Thesmophoria, 1894-1897, Francis Davis Millet (via Wikimedia Commons)

Thesmophoria

The Thesmophoria was not a festival limited to Attica; far from that, it was one of the most widely-celebrated in the Greek world. It was held annually, mostly around the time of sowing, in honour of Demeter and her daughter, Persephone. It was restricted to adult women, and the rites practised during the festival were kept secret. The celebrations aimed at promoting fertility, both human and agricultural; they are believed to have included animal sacrifices as well as rites symbolising Persephone’s descent into and ascent from Hades. It was famously parodied in Aristophanes‘s comedy Thesmophoriazusae.

Hermaea

As evidenced by its name, the festival of Hermaea, celebrated in various parts of Greece, was dedicated to the god Hermes who was, among else, a protector of athletics. The festival featured athletic competitions, usually held in gymnasia and mostly restricted to young boys, hence having a rather unofficial and playful character compared to other competitive games. It is believed to have taken place in various other parts of Greece as well.

Apaturia

Apaturia was a religious festival held annually by nearly all the Ionian towns; in Athens, it took place in the middle of the month Pyanepsiōn (October/November), and lasted for three days, on which occasion the various phratries (clans) of Attica met to discuss their affairs. Its name is believed to signify the festival of “common relationship”. Athena, Zeus and Dionysus were also honoured. On the third, called Koureotis (from kouros, young boy), male children born since the last festival were presented by their fathers or guardians; after an oath had been taken as to their legitimacy, their names were inscribed in the register.

Left: Procession of male pairs (possibly Apaturia festival), Attic red-figure kylix, ca. 480 BC (by User:Bibi Saint-Pol via Wikimedia Commons); Right: The priestess of Bacchus, 1885 – 1889, John Maler Collier (by via Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Procession of male pairs (possibly Apaturia festival), Attic red-figure kylix, ca. 480 BC (by User:Bibi Saint-Pol via Wikimedia Commons); Right: The priestess of Bacchus, 1885 – 1889, John Maler Collier (by via Wikimedia Commons)

Pyanopsia

The festival of Pyanopsia (or Pyanepsia) was held in Athens in honour of the Apollo, god of light, healing and music, also in the month of Pyanepsiōn, which was actually named after the festival. Pyanopsia means “bean-stewing”, in reference to the sacred offering of a rich pulse stew to the temple of Apollo, to honour of the autumn harvest. People also thanked the god with the offering of the eiresione, a branch of olive or laurel, bound with purple or white wool, and adorned with fresh fruit and small pastries made with honey, oil and wine. The branch was drizzled with wine and carried in procession by a chanting boy to the temple of Apollo, where it was suspended at the gate. According to some sources, the doors of houses were similarly decorated; this too is considered a predecessor of Christmas decorations.

Haloa

Haloa was an agrarian festival held annually in the month Poseideōn (December/January), after the first harvest was over. It took its name from the threshing floor (halos), around which it took place, and was dedicated to Demeter, Dionysus and Poseidon. It was mostly observed by women and men were generally excluded, hence its rituals have been poorly recorded. It probably featured mysteries of a symbolic character, similar to those of the Dionysia and the Eleusinian Mysteries.

You can use a date converter to find out when these (and several other) festivals would be celebrated today.

Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica, Oxford Classical Dictionary, Wikipedia

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Apokries: The Greek Carnival; Carnival Festivities around Greece; Greek and Roman origins of Christmas traditions; Kerameikos, the necropolis of Athens; “Eleusis, the great mysteries” at the Acropolis Museum

M.V., N.M. (Intro image: Thesmophoria [detail], 1894-1897, Francis Davis Millet (via Wikimedia Commons)

TAGS: ARCHEOLOGY | HISTORY