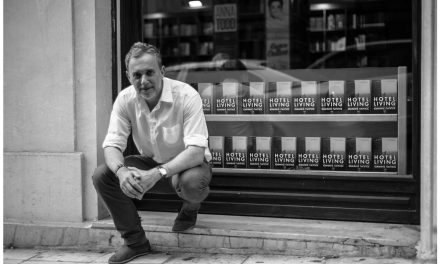

Dimitris Angelis (Athens, 1973) has published seven collections of poetry, as well as essays, studies and short stories. His collection Anniversary was awarded the Porfyras Prize of the Academy of Athens, in 2015 he was honored with the Corda Foundation Translation Award and his collection Οn my Bed, a Deer in Sorrow was awarded with the National Poetry Prize. He was Editor of Nea Efthini literary magazine (2011-2013) and he is actually Editor of Frear (National Prize for the best literary magazine, 2014). He is president of Poets’ Circle in Greece and director of the Athens World Poetry Festival.

Dimitris Angelis spoke to Reading Greece* about the main themes his poetry delves into, explaining that he has always been “interested in conversing with the present, collective or personal, in creating [his] own recognizable landscape which everyone may find appealing”. He also talked about Poets’ Circle, “created out of the need to provide more space and importance to a literary genre [that]…remains marginal and often undervalued”, as well as about the challenges he was faced with regarding the Athens World Poetry Festival, which this year went digital. He also commented on the prospects ahead for books, considering that the successive crises have adversely affected the book market and concluded that “literary books mythologize our life, while scientific books offer food and yardsticks for thought; in our times both dream and critical thought are more indispensable than ever”.

In her review of your latest poetry collection Yesterday, Αnthoula Daniil comments on the way the present interweaves with the past, as well as on the interrelation of pain and loss with the will for life. Tell us a few things about the book.

Actually it’s not a book but rather a single poem illustrated by the painter Kostas Siafakas; it was a private publication and I was honored by Anthoula Daniil’s critical review. In any case, the poem is part of a new poetry collection, which indeed refers to the issues of loneliness, anguish, absence, the same time that writing becomes an act of liberation translated into a desire to live. The poem titled Yesterday is the last of a unit comprising love poems with concrete reference to the pandemic – the historical present cannot be absent from our writings. The rest three units of the forthcoming book refer to “every day sorrows”, details from travels in various parts of the world, along with scenes from the favorite Andrei Tarkovski movies.

Which are the main themes your poetry delves into? Would you say that there are recurrent points of reference in your writings?

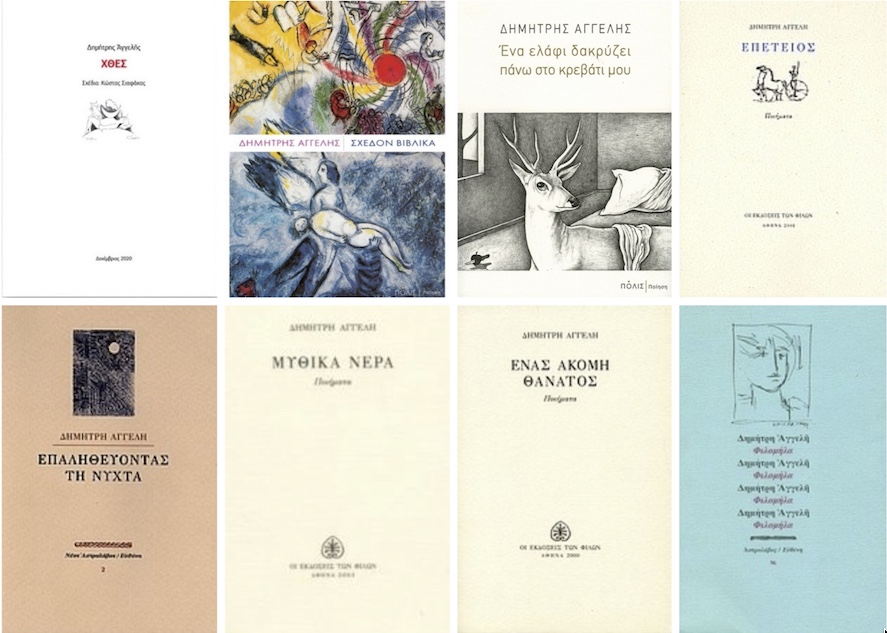

Looking at things from a distance (as if watching yourself naked, laid down on the anatomy table, that is already dead), I would say that following my first two writing attempts in poetry (Philomel, One more death), I proceeded quite naturally to a trilogy of books aiming to relate myth, especially the Iliad and the Odyssey, with the Greek history and my own life. (Waters of myth, Anniversary, Verifying the Night). Waters of myth was written during my military service and thus the literary language of the Iliad was paired with my own experiences; many of the poems of Αnniversary are connected to the Odyssey given that I wrote the book when I already had my first daughter and at the same time good friends and partners were beginning to die. The third book, which comprises only two poems and is political par excellence, is based on two of my literary myths, Yiannis Ritsos whom I put watching the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 on TV, and the Waste Land by T.S. Eliot.

Then came the economic and social crisis and I felt I had to express on more direct terms what we were experiencing, without the myth intersecting with everyday life. I thus moved to a more surrealistic language in order to describe, as much as possible, the insanity we were faced with. The respective book, bearing the strange, long-winded title On my bed, a Deer in Sorrow had a certain appeal, received the National Poetry Award and was translated, thus I reckon that in a way, it expressed the historical conjuncture as it was intended, without however resorting to the vulgarity of easy politics and social critique, elements that I am personally repelled by when I come across them in literature. There followed Almost biblical, a very personal book on loss and my personal grieving, in which I used fragments of narrations and images from biblical texts, all of us know since childhood or which look in a way familiar. Thus, I reckon I have always been interested in conversing with the present, collective or personal, in creating my own recognizable landscape which everyone may find appealing, irrespective of education or their readings. In case you notice a melancholic obsession on lack, the refutation of dreams, to a sense of ending, it’s not my fault, that’s how life is. And, in the final analysis, they may console us and maybe make us a bit affectionate to the others.

You are the president of Poets’ Circle, which aims to bring poetry to the forefront. Tell us a few things about its philosophy and the initiatives it has undertaken during the last few years.

Poets’ Circle was created out of the need to provide more space and importance to a literary genre, which although it has offered our country two Nobel Prizes, it remains marginal and often undervalued. Thus, Poets’ Circle has undertaken a number of initiatives: we turned the month of March into a month of poetry with events throughout Greece, we initiated the Athens World Poetry Festival and interconnected it with other festivals and the Versopolis pan-European network, we invited major foreign poets in Greece and open the way for our poets to take part in foreign festivals etc.

I am personally interested in two things: on the one hand, to organize long lasting, binding events and institutional co-operations so as to avoid actions that are soon abandoned due to fatigue or indifference. On the other hand, that whatever we organize should be of high quality, fostering culture against the tawdriness of our times, without however resorting to naïve, poetic-like happenings or to be trapped in politicking which debase and annul the public image of poetry and poets. As Walter Benjamin eloquently put it: “The artist creates a work. The primitive is expressed through documents”. Poetry may constitute a political document, but is not primarily that. I am interesting in supporting poetry as an autonomous act and an art of the dense discourse; a critical approach to our era may have a sociological interest but it is of secondary importance.

This year, due to the health pandemic, the Athens World Poetry went digital and was, nonetheless, met with success. Which were the main challenges you were faced with?

2020 was a difficult year for all of us; many festivals around the world were cancelled, some others went bankrupt given that their opening coincided with the lockdown, and most of them went digital. We were preparing our usual festival, but have, at the same time, predicted the ban on cultural events imposed in early September, just a few days before our official opening. Thus, we have asked for videotaped readings by important poets from around the world (Adam Zagajewsky, Paul Muldoon, Yolanda Pantin, Jack Hirschman, Dunya Mikhail etc.) and presented them on our youtube channel, we awarded this year’s Barbara Fields Siotis Award to the major Chinese poet Bei Dao, while we organized two debates on Greek and foreign poetry, videotaped readings with Greek and foreign poets we had here, while new actors and writers, as well as distinguished artists, contributed to the festival’s promotion and thus it remained alive and one could say that in the end it was met with success.

I reckon that it is under difficult conditions that the collective spirit that we so much need is brought to the surface; poetry needs to be combined with music, theatre, painting, cinema – these are the cooperations we aspire to. Let me conclude with one last remark: undoubtedly covid with its various mutations will stay with us for a long time. Yet, we should not think that festivals and poetic events around the word (as education and a number of other activities) will continue to be digital or, as it is stressed digital as well. The warmth of human contact, the expressiveness of the corporal movement can in no way be imprinted onto a more or less blurred image coming out from the dimly lit desk of a poet, who looks like a psychiatric inmate. Festivals are important not just for public readings but mainly for the debates and meetings that take place on the sidelines. I strongly believe in them because I feel that my participation once in a festival in remote Nicaragua opened my eyes to other readings, to writers I didn’t know, while the acquaintances I made literally transformed my poetic perception in general.

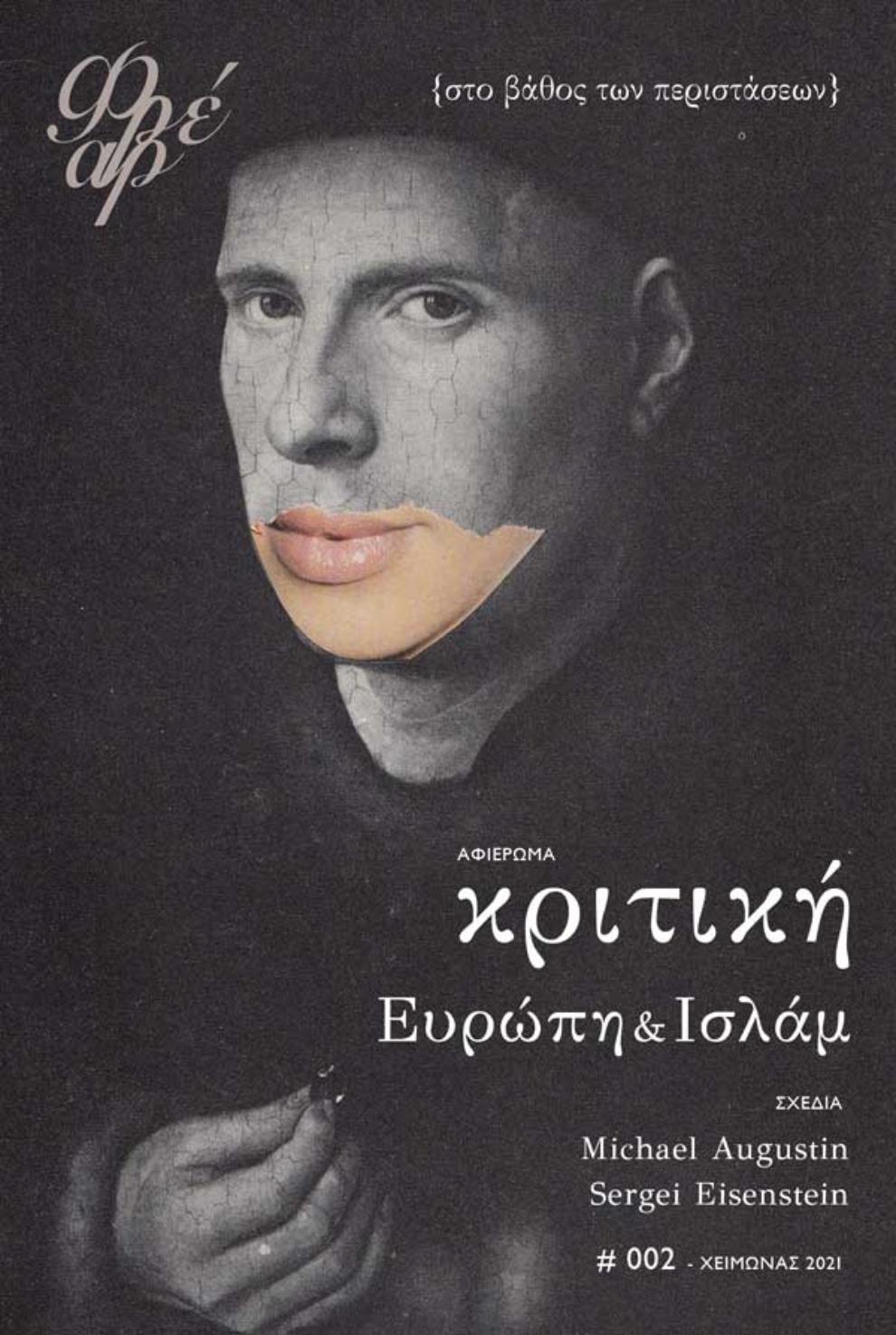

You are the director of frear magazine, one of the most respected literary magazines in Greece. How did you embark on such a venture? Tell us a few things about its scope and content.

Frear was created within the crisis following an outburst. At the time, I was at the wheel of another journal, when I was confronted with our publisher who wanted to intervene in the content and devalue the nobility of an open and unselfish effort. In this respect, Frear constitutes a venture: the whole editorial board and the basic partners stood down and started to create anew, with no funding at all, a new literary magazine the way we wanted to. I feel that ruptures, when pursued in order to protect quality and dignity, are more than fertile and creative. Frear published 28 printed issues, with some of the most important contemporary Greek and foreign writers, while its interviews would be envied by major newspapers (Yves Bonnefoy, Mark Strand, Alain Badiou, Margaret Atwood, Michael Walzer, Jean-Luc Marion etc). It has organized tributes and important events, while in its website there were published texts distinct from the printed edition on a daily basis. It was awarded by the Ministry of Culture and is now moving forward to a new era.

Given that due to the pandemic we were faced with the problem of distribution to closed bookstores as well as with financial issues, we decided to make Frear an online journal with free access to all. We are not interested in profit, we never were; what matters for us are the texts. Our initial enthusiasm remains undimmed and our scope is always the same: not to become a respectable gallery of personalities or a more or less text depository; to remain an open, creative community conversing with the world when everything around us points to the opposite.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: literary magazines, blogs, festivals, readings in public squares to mention just a few. How would you comment on this strong civic awareness?

There is both a positive and a negative side. On the one hand, it means that poetry hasn’t lost its prestige, and there are many who deem it as important in their lives, they express themselves through poetic writing. Yet, on the other hand, there is such bad poetry out there; so many events, so many blogs, causing confusion as to how a poem is evaluated and established. As with a crisis in public discourse in general, there is a crisis in the literary field as well, though fortunately its consequences are less detrimental. Yet, there is a question to be answered, as in the case of paraliterature: would you prefer that people read poetry no matter how bad or not read at all? Although a bit hesitant, I would answer that I prefer that people read poetry, even if it’s bad, since I hope that through reading they will come across that good poem that may change their lives.

Both the recent socio-economic crisis and the current covid-19 crisis have adversely affected the Greek book market. What are the prospects ahead for books? Could digital books offer a way out?

These successive crises have adversely affected the market in general and maybe even more the sensitive book market. Considering that bookstores are closed, small publishers, who don’t have a great potential to promote and distribute their production, do not invest in newcomer writers, poetic or specialized works, and this constitutes a blow for everybody. Equally cautious are big publishers, while many small bookstores either shut down or have to lay off their personnel. The losses are numerous and the digital book, apart from the fact that it’s unprofitable in a small market like ours, doesn’t seem to attract readers. And here arises another problem: the digital book is not met with success because younger generations, which are more acquainted with screens, have not been inspired towards reading – ardent readers are middle-aged and older. To a great extent, my generation prefers the smell of paper.

It has been argued that what the Greek book market lacks is a concrete and purposeful state policy. What should be done at state policy level for the promotion of Greek books?

I reckon that since the abolition of the National Book Center of Greece (EKEBI) no government has seemed willing to replace it with another operational institution, although EKEBI’s actions have not always been to the right direction. I consider that it’s positive that gradually its responsibilities are transferred to the Hellenic Foundation for Culture, which may contribute to the extroversion of the Greek book. One of the major problems has to do with fragmentation. The book falls within the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Culture, libraries belong to the Ministry of Education, while Modern Greek Studies Departments abroad to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which renders a common policy difficult. What we need are longstanding book-friendly institutions within the framework of a concrete policy and not just financial support of publishers or bookstore owners, as they themselves want. I believe that through small steps, such as the re-initiation of programs fostering readership at schools and the funding of translations of Greek works abroad, the financial support of the participation of Greek writers in international festivals and literary events, the support of events in commemoration of specific writers, may render significant results.

Literary books mythologize our life, while scientific books offer food and yardsticks for thought; in our times both dream and critical thought are more indispensable than ever.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Dirk Skiba

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE