Reverend Dr Andreas Andreopoulos is Reader in Orthodox Christianity at the University of Winchester and a priest of the Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain. His research and writings cover the study of the Fathers of the Church, Christian Iconography and Symbolism, the study of Liturgy, and modern Orthodox thought. His publications include Metamorphosis: the Transfiguration in Byzantine Theology and Iconography (SVS Press, 2005), Art as Theology: from the Postmodern to the Medieval (Equinox, 2007), This is my Beloved Son: The Transfiguration of Christ (Paraclete, 2012), and Christos Yannaras: Philosophy, Theology, Culture (ed.) (Routledge, 2019). He has been leading the study of Orthodox theology at the Master’s and PhD level in Winchester University, and he recently founded a book series, based at Winchester University Press, dedicated to the study of modern Orthodox thought, titled Modern Orthodox Dialogues.

Rev. Dr. Andreopoulos spoke to Rethinking Greece* on how the Orthodox tradition and its ideals of forgiveness and communal being can help us navigate and reflect on the problems of the modern world; what attracts many Westerners to Orthodoxy; on the Orthodox liturgical worship and its power to transmit a knowledge beyond words; the relevance of Greek philosopher and theologian Christos Yannaras‘ thought today; iconography as a way to express the inexpressible; Greek Diaspora and the Ecumenical tradition of Orthodoxy; the need for meaningful interfaith contact; and finally, on why the meaning of the Scriptures could be summarized in one phrase: “love is stronger than death”.

One of Christos Yannaras’ most famed texts in Greece is Finis Graeciae (1986), where he laments the prevalence of “western/Enlightenment” values such as the market, economic relations and the pursue of personal interest, over the more communal values of tradition, historic memory and cultural identity. Do you think his criticisms are still valid today? What could a true Orthodox faith and practice mean in modern Greece?

I am afraid that texts like that are even more relevant now than they were 35 years ago. The voice of Yannaras was not the only one warning us of such dangers. There have been many other critiques of our times and the challenges we are facing, both within Greece, as well as internationally. Overall, there is a great concern that we are moving towards a new era of barbarism, something we see with the international decline of education, language, the arts and the humanities. Likewise, the Western political and cultural paradigm sacrifices the values of historical memory and cultural identity, not so much for the sake of transcending ethnic and cultural differences, but either responding to a collective guilt for the sins of colonialism (something that applies also to cultures with no Enlightenment colonialist past, such as Greece), or striving towards a consumerist value system, for which spiritual values (in both understandings of the word ‘spiritual’, as in ‘the human spirit’ and as in ‘spirituality’) are an impediment.

The answer to such challenges can never be to turn back the clock, in a hopeless and meaningless atavism. Nevertheless, as technology and the media, (traditional media and social media) change our life more rapidly than we could ever anticipate, philosophical and spiritual reflection on the way forward is vital. This suggests that it is necessary to identify and address many of the causes of the current crisis, politically, spiritually and culturally. This kind of paradigm examination may take us back a few centuries, when the system that today we recognize as cruel, consumerist, mechanistic, based on exploitation, was founded, and could not overcome such problems in spite of the impressive advancement of technology.

Many characteristics of Orthodox Christianity, such as its insistence on a more-than-rationalistic gnoseology, its stress on communal being, its ideals of forgiveness and personal asceticism, may be extremely useful to us today

There is much in the Orthodox tradition that can help in this direction. Undoubtedly, several elements of the structure of the Christian tradition express only their times, and as such may not be relevant today. Nevertheless, the foundation of Christianity as the meeting between God and his Creation, and the Orthodox tradition as the strand that is probably less tainted by the reductive Enlightenment rationalism than the other Christian traditions, can help us find a way forward. There are many characteristics of Orthodox Christianity, such as its insistence on a more-than-rationalistic gnoseology, its stress on communal being, its ideals of forgiveness and personal asceticism, that may be extremely useful to us today.

Yannaras has been proclaimed as “one of the most significant Christian philosophers in Europe” by Rowan Williams, theologician and Archbishop of Canterbury (2002-2012). International interest in Yannaras’ thought has been on the rise lately: in 2020 two English-language books on Yannaras were published: “Polis, Ontology, Ecclesial Event: Engaging with Christos Yannaras’ Thought” and “Christos Yannaras Philosophy, Theology, Culture” (edited by you and Demetrios Harper). What are the aspects of his thought you believe are more salient today from an international perspective?

I believe that the contribution of Yannaras can be considered at an international perspective, even if in some cases it may be necessary to locate touch points between the Greek tradition, which Yannaras knows very well, and other traditions. Some of his great themes, that are expressed in several ways throughout his work, and can be great entry points in considering our position as a Greek, a European or a global culture, include:

a. The pursuit of knowledge and understanding in a way that does not separate the truth as an experience and its empirical confirmation, from reason – a demand that may be found in most of the Orthodox Christian tradition. In many ways the separation between experience and reason that took place some time in the Medieval West and has defined since then what is now international consumerist culture, has led to the autonomy of reason, to rationalistic absurdity. The greatest political totalitarianisms of our time, for instance, communism and fascism, are examples of such impositions of ideologies – separated from empirical confirmation – on human life and values. Yannaras, in many of his books explores the space between what can be articulated in rational thought – the effable – and what may be experienced but may not be articulated – the ineffable.

b. The understanding of society as having a much more profound foundation compared to what we experience today. Yannaras often distinguishes between the Greek concept of koinonia (the word that is normally translated as society) and the Latin-based societas, with its conceptual descendants in modern European languages. Whereas koinonia implies a common life and existence (something that may be seen by the fact that it is the same word for sacramental communion), societas (and society) are primarily associations of individuals that wish to promote their common interests, very closely related to what we would now call a commercial association or company. This distinction between koinonia and societas shows two fundamentally different foundations and/or directions of civilization. Much of the political thought of Yannaras is based on this.

The criticism of the West by Yannaras, is a self-criticism, an attempt to recover the spiritual and cultural ontological foundations of our own culture

c. Modern Western thought since at least Nietzsche, has deconstructed critically much of the intellectual edifice of Christian spirituality, and it has attacked the institutionalization of Christianity. While this may seem like an attack on religion, several Orthodox theologians, such as Christos Yannaras and Nikolaos Loudovikos, have engaged constructively with Nietzsche’s thought. The crux of this engagement is at the same time a critical examination of the past, and a pursuit for the ‘lost Christianity’ that Nietzsche did not experience. Through books such as Countergift to Nietzsche and Against Religion, Yannaras incorporates post-Nietzschean philosophical thought to his exploration of modern theological thought.

d. Related to the previous point, Yannaras often criticizes modern Western culture. This is often mistaken for an anti-Western (anti-American, anti-European) position, similar to a pro-Eastern (pro-Russian, pro-Oriental) political stance, with reference to a Cold War understanding of what is West and East. The reference of Yannaras to East and West however, has to do with the Greek, Greco-Roman or Byzantine (Eastern and Western) culture vs. the Latin/Gothic roots of modern culture, to which we inevitably belong. The criticism of the West by Yannaras, is a self-criticism, an attempt to recover the spiritual and cultural ontological foundations of our own culture, rather than an attack on a foreign, invading culture.

e. In relation to Christianity, Yannaras often laments the collapse of the Christian spiritual tradition to what may be compared to political parties – a criticism that includes the Orthodox Church. Christianity was never meant to hold any absolute measure of the truth – if nothing else, the Truth in the Gospel is one of the names of Jesus Christ. The elevation of Scripture (for Protestants), the Magisterium (for Roman Catholics), or of the formality of the past (for the Orthodox) to absolute measures of the truth, misses the point. Instead, Christianity is meant to define itself as a living community, where the measure of truth is relationship – with each other as well as with God.

f. Finally, in terms of the state of the Christian Church today, while as a model of gathering, the ancient Christian Church, following in the footsteps of the ancient Greek polis and the ecclesia tou demou, put forth an ecumenical invitation, where every possibility of the human existence was recognized – and therefore for several centuries in the East and the West the Church transcended ethnic, cultural and linguistic divisions – at some point after the Reformation the Church became subservient to the state. Thus, we have the foundation of ethnic churches. This situation and mentality has unfortunately passed also to the Orthodox Church. While the Patriarchate of Constantinople, despite several mistakes, still stands as a beacon of ecumenical (today we would say international, or global) Christianity, much of the politics in the modern Orthodox Church is shaped according to local, ethnic and narrowly political lines. Yannaras often talks about this loss of ecumenicity and the need to redefine Christianity as an ecumenical community.

You are responsible for postgraduate degrees in Orthodox theology at the University of Winchester. What are the backgrounds of your students?

Today we live in a difficult time in regard to the humanities, all over the world. Yet, it is touching that in the last fifteen years, which is how long I have been in the UK, and I have been teaching Orthodox theology at the undergraduate, the postgraduate and the doctoral level, there is a thirst of non-Orthodox to learn and understand the Orthodox tradition. Most of my students are not Orthodox, and of course as I teach at what may be described as a secular university, as opposed to a seminary, there is no expectation of faith compliance. Many of my students are people who are exploring the roots of (their own) Christianity, or who face dead ends in modern Western Christianity and are looking for ways to address them. In the course of their study, some of my non-Orthodox students converted to Orthodoxy.

My goal as a teacher is to make sure that the Orthodox voice is heard and understood clearly, and that it is taken seriously in the wider Western spiritual context

Nevertheless, my goal as a teacher is not to suggest that Orthodoxy should confront and replace Western denominations. Instead, it is to make sure that the Orthodox voice, inspired by the tradition of the Fathers, the liturgical tradition, and the thought of modern Orthodox thinkers, is heard and understood clearly, and that it is taken seriously in the wider Western spiritual context.

In one of your interviews you say that “for the first time in centuries, many Westerners look to Orthodoxy for a glimpse of an alternate way of worship, prayer, and living”. Why do you think that is? What does an Orthodox approach to worship entail?

I would like to answer this by recalling something that happened a few years ago, when I was working in a small community in Wales. Since everyone knew everyone else in that small place, and there two Anglican churches, one Methodist, one Presbyterian, one Baptist and one Roman Catholic Church, along with the emerging Orthodox Church, the local priests and ministers had the custom of visiting each other’s churches at the beginning of Holy Week, as a sign of Christian fellowship. This was the first time they invited me, as the representative of the Orthodox Church which had just been founded in the area. I remember it was a lively and friendly group of people (eight to ten, perhaps). We visited all of these churches saying a prayer in each one of them. On the way from one church to another we were a jovial group, talking a lot. At the end we went to the Orthodox church, which was simply a rented space, the vestry of the Presbyterian church, where we had erected a primitive iconostasis. As they entered, the group immediately stopped talking. I cannot say if it was the lingering smell of incense, the icons, but the whole echo of the liturgical worship of the Orthodox church is something they all felt immediately, which staggered them. They stayed in complete silence for a few minutes, I sang a hymn of the Holy Thursday service, and we left.

As we were leaving, I was thinking that the contribution of the Orthodox Church in the West is precisely this. If the question is social work, activism, knowledge and so forth, other denominations are doing fine, much better than us. But if the object of worship is to manifest a different way of being, to live something of the Kingdom of God, not just as an ideological abstraction but as an experience, if the point is to manifest the presence of God among us, then the Orthodox liturgy is unparalleled – something that brings us back to the Russian envoys to the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople in the 10th century, when they reported to their leader that “We no longer knew whether we were in heaven or on earth, nor such beauty, and we know not how to tell of it. We only know that God dwells there among the people, and their service is more beautiful than the ceremonies of other nations.”

If the object of worship is to manifest a different way of being, not just as an ideological abstraction but as an experience, then the Orthodox liturgy is unparalleled

Such incidents are indicative of what many Westerners miss in their own tradition, and they often find it in Orthodoxy. Too often the liturgical services in Western churches feel like a rational exercise, or they are centred on the sermon – very often the same kind of Biblical analysis that I would do at the university, or, worse, a moralist exhortation that does not scratch the surface of the ontological drama of the meeting between humanity and God. Very often, Westerners are enchanted by what they perceive as the ‘mystical’, or the ‘mysterious’ Orthodox Church. Although I understand what it is they sense, the terms ‘mystical’ and ‘mysterious’ are not correct, at least not in the way they are understood usually in this context. Instead of an undefined and somewhat nebulous ‘mysticism’, the Orthodox liturgical worship has the power to transmit a knowledge beyond words, to make manifest the presence of the Holy Spirit, and to allow the people to enter the way of life that includes the life of God. This is not automatic of course, it depends on each one’s participation, but at least the possibility is offered.

The liturgical language, which has been shaped under the influence of ancient drama, and has developed it further, including the development of the language and symbolism of icons, is the most complete way we know to transmit the experience of the sacred, and to facilitate the meeting between God and humanity. While not every member of the church may participate in the same way or to the same degree, they all sense this in some way.

The Orthodox tradition is firmly grounded on the liturgical worship tradition, although it is possible to make similar observations about the ascetic prayer as it is practiced within the monastic circles. Much of the thought and culture of Orthodoxy is fed and informed by it, much more than we can say about Western denominations. While other denominations may be more successful in terms of social work or administration, I believe it is precisely this foundation of intense worship that allows Orthodoxy to carry a theological and ontological depth that is not found in them.

You have studied iconography-as-theology, and talked about how art can express spirituality and even thoughts better than words. Could you tell us more on that? What are some examples of Greek iconographers that engage with this tradition?

In many ways art is more privileged than philosophy or systematic theology, when it comes to expressing things that cannot be put to words. This is certainly the case with the spiritual experience, which exceeds our rationale – an entire branch of Orthodox theology is dedicated to this kind of experience-overcoming-words, known as the apophatic tradition. Iconography, more than any other spiritual art (second perhaps only to liturgy, which nevertheless may not be shared outside its time and place) has been developed as a way to express the inexpressible. People formulated their theological thought while they were facing an icon, praying. In the history of iconography we have several examples where a theological idea is first expressed in iconography and only years or even centuries afterwards it is expressed in words. In addition, the exploration of spirituality through iconography (or all kinds of art, for that matter) connects the pursuit of spirituality with the pursuit of beauty. For this reason the aesthetic experience that nevertheless points to its spiritual foundation, is something that may be shared and perhaps also understood also by people who may not identify themselves as faithful.

Iconography, more than any other spiritual art, has been developed as a way to express the inexpressible and connects the pursuit of spirituality with the pursuit of beauty

There are many examples of ancient and Byzantine art that is still extant, and although we have some names of famous iconographers, the vast majority remains unknown to us, because they did not care to make themselves known, or to sign their works. More recently however, we can see a regeneration in iconography. One very interesting observation here is that while other aspects of church art (music, architecture, liturgy) remain quite conservative, and do not show signs of dramatic development, iconography in the 20th and the 21st century has become quite daring, and experimental.

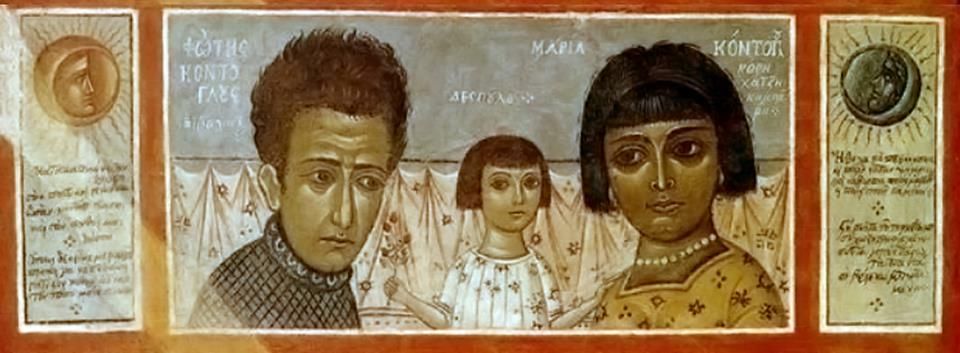

In the Greek tradition this starts with Photis Kontoglou, who turned, for the first time after centuries, the interest of people to traditional iconography, and was the teacher of some of the most famous modern Greek painters, such as Yiannis Tsarouchis and Nikos Eggonopoulos. I do not think that the contribution of Kontoglou has been recognized for what it is, yet. It was he, in the beginning of the 20th century, who captured the theme of the Greek identity, as a Greek artist in Paris, having experienced two successive migrations. He later transplanted this theme to Karolos Kuhn, the founder of modern Greek theatre, who recognized his debt to Kontoglou. It is precisely this milieu that made it possible for artists such as Hadjidakis and Theodorakis to turn their attention to the Greek tradition and to create what later became known as the artistic boom of the 60s. Modern Greek culture owes much to Kontoglou.

Other than that however, there are many Greek iconographers today, who have internalized the theological demands of their generation (such as those we explored in Yannaras), and express them in an aesthetic that follows firmly in the older tradition, yet with a daring way that makes it relevant today. Some of these iconographers are Rallis Kopsidis, George Kordis, Markos Kampanis, Stamatis Skliris, and my personal favourite Michalis Vasilakis from Crete, who died recently.

For Greeks and other Christian Orthodox peoples, their religion is bound to their ethnicity. This is especially true of Greeks living abroad. Could you talk to us about Orthodoxy and Diaspora, as you yourself have lived in many countries around the world?

I think the best way to consider this is by remembering that traditional Orthodoxy was ecumenical, i.e. it respected the language and the customs of a people and did not try to change them, as was, unfortunately, often the case with Latin missionaries. The greatest example of this is perhaps the Christianization of the Balkans. In order to transmit Christianity to these populations who did not have a written language, the Greek missionaries invented an entirely new alphabet for them (Cyrillic), so that the Gospel and the liturgical books could be translated and written down for them. This, of course, became the alphabet that most Slavic nations still use.

Likewise, Greeks for many centuries, were almost by definition cosmopolitans, citizens of the world. In this way they would feel comfortable and they would make a good home in any place, such as Alexandria, Iasi, Vienna, or London. It is only fairly recently, after the 19th century that Greek migrants were mostly destitute and uncultured, the people who could not make it back home – although the present financial crisis seems to have changed this. Be that as it may, the Diaspora in the past, and perhaps also in the future, was a cultured elite, quite integrated to the place in which they lived. Likewise, Orthodoxy as the expression of ecumenical, rather than local Christianity, can help people create a spiritual identity that transcends their ethnic background.

I believe that as Greeks and as Orthodox, we preserve a tradition of being, thinking and worshipping, for the sake of the entire world, and not just for our own sake

Having said all this, perhaps this point is the most immediate problem faced by modern Orthodoxy. While there was always a connection between religion, culture and identity, in the last century these concepts became exclusivist, inward, rather than inclusivist and ecumenical. It is sad, for instance, to see that for the first time ever, as we saw in 2016 in the Crete council, Orthodoxy defines itself as a communion of ethnic churches. Perhaps this is something that we will overcome. The challenge for modern Orthodoxy is to make a choice of direction between a narrowly defined ethnic church (Greek, Serbian, Russian, Romanian, etc.), which will lead us to further division and will marginalize us in the West, and an ecumenical version of Christianity, a communion that preserves some of the principles of the ancient Church before they were distorted by the Western Renaissance and Enlightenment, which can dialogue with confidence with the big questions of our time. The bottom line, I believe, is that as Greeks and as Orthodox, we preserve a tradition of being, thinking and worshipping, for the sake of the entire world, and not just for our own sake.

Due to globalization, immigration/refugee flows and other socio-economic factors, most modern societies are multi-cultural and multireligious. What role could Orthodox Christianity -Ecumenical by definition- play in this context and how could it contribute to interfaith dialogue?

This question follows naturally from the previous one. There has always been a dialogue among cultures and traditions, but in our times this dialogue is more intense and faster than ever before. Throughout history some cultures disappear, while others emerge. At this time, within global history I believe it is essential to offer to the world the best parts of our culture and tradition, the challenges and the riddles that we have collectively gathered throughout the centuries. It may be difficult to encapsulate the entire Orthodox tradition in a few short phrases, but the ecumenical spirit we find in early Christianity, the ecclesiological model of consensus through dialogue (instead of decision by vote of majority), the image of the priest and the bishop as the father of his community instead of its administrator, the liturgical and worship foundation of every other activity, and finally the demand for a metaphysical and ontological depth in our theological language, are some of the most important gifts that Orthodoxy may bring to the global spiritual community. Naturally, these points are ongoing challenges for ourselves, to begin with, instead of givens that we possess. But at least they are clear as directions, I will dare say as ascetic directions in our tradition and in our practice.

An act that would go down with a bang and would offer to interfaith trust more than two centuries of diplomacy for instance, is an extended visit of the Pope to Mount Athos

As for interfaith dialogue, I believe that it is not sufficient if it is conducted simply at the level of exchange of ideas. The rift between the East and the West (and likewise, between the Roman Catholic Church and the several Protestant Churches) is primarily psychological rather than theological. There is a lack of trust and a fear of the Papacy by many Orthodox, because the memory of the Fourth Crusade is still strong, after nine centuries, despite the apology of Pope John Paul II during his visit to Greece. I believe that for a meaningful interfaith contact we need to see daring movements that go well beyond the standing dialogue committees. One such way may be for Western leader to try to understand the nature of this ‘anti-ecumenical’ reaction to interfaith dialogue. An act that would go down with a bang and would offer to interfaith trust more than two centuries of diplomacy for instance, is an extended visit of the Pope to Mount Athos, where he would have the chance to hear some of the most serious and respected anti-ecumenical concerns, to understand something of the spirituality of that place which is, in many ways, the conscience of much of the Orthodox world, but at the same time such an extended visit (despite any conditions that may be placed on him by the Athonites) could be the act of humility that only a true leader and caring father would be able to demonstrate. It is only after some sort of establishment of trust that we may start a meaningful interfaith dialogue.

What are the main challenges facing Orthodox Christianity today? How can faith be kept alive in an increasingly secular world?

There are several challenges that we could mention in relation to the operation, the administration and the culture of the Orthodox Church. I am sad when I see that a good part of Orthodox faithful express an ideological kind of Christianity, or Orthodoxism (as opposed to Orthodoxy) that is marked by fear, hate, distrust of science and outsiders, and precisely the kind of legalism that the Gospel came to liberate us from. Nevertheless, I believe that this is a loud minority, and does not reflect the true content of the Church.

At any rate, this is perhaps not the most important challenge for us. I believe that what is even more important, in our time as it always was, is to consider the great challenges of humanity, such as death and immortality, life in the Resurrection, love for those who make it difficult for us to love them. The Church is primarily a workshop of love, a continuous examination of how we can live for, in and with a God whose name is love.

The Resurrection tipped the ancient balance of love and death; therefore I believe that the meaning of the entire Scripture in one phrase can simply be “love is stronger than death”.

If we were to condense the meaning of the entire Old Testament in one phrase, I believe it would be the phrase “love is as strong as death”, from the Song of Songs. And if we were to condense the meaning of the entire New Testament in one event, it would be the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, the God who is love, and whose Resurrection showed the world that he could not be bound by the physical limitation of death. In this way, the Resurrection tipped the ancient balance of love and death. Therefore, I believe that the meaning of the entire Scripture in one phrase can simply be “love is stronger than death”. If we start by considering Christianity, our life, our relationship with each other, our relationship with our planet and our environment, at that level, if we demand that we consider social, environmental, financial, political problems, in the context of the eternal ontological drama that involves and bonds God and humanity since the dawn of time, does it not bring a different perspective to our mundane problems? I believe that this is why secularism is not enough. It is too limiting a worldview, too uninspiring and uninteresting as a way of thinking, and I hope that it will collapse under its own weight, when humanity realizes that it is staying away from the really big questions of our existence. Nevertheless, this also shows what the responsibility of Christianity is – precisely to remind us of these big questions with the immediacy and the directness that we can find in strong love and in death itself!

* Interview by: Ioulia Livaditi

TAGS: HERITAGE | ORTHODOX CHRISTIANITY | RELIGION