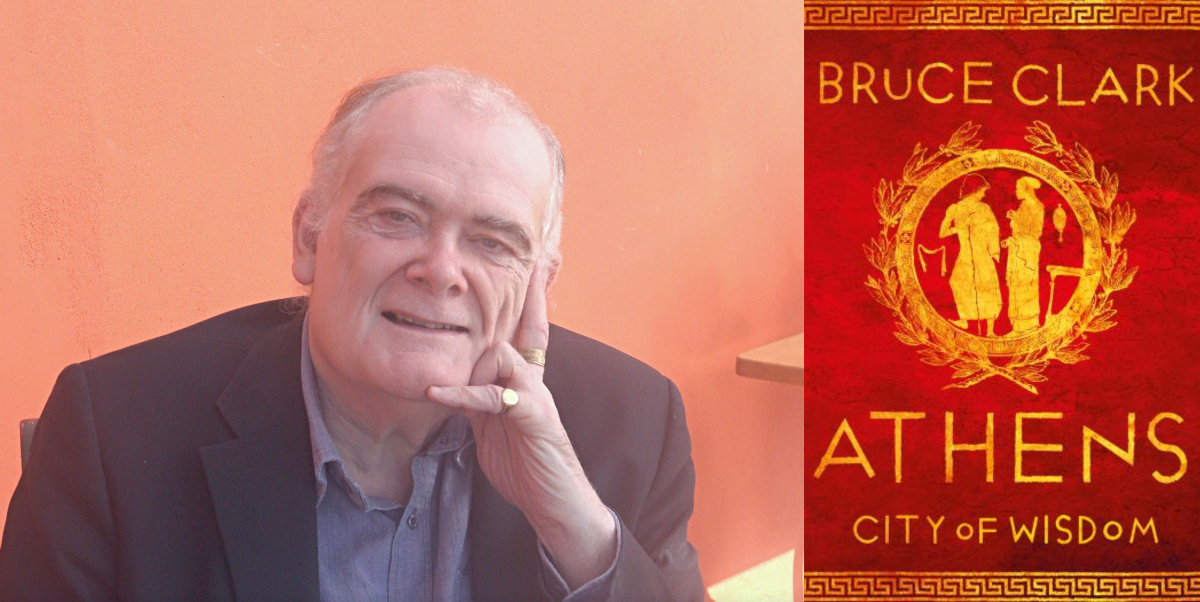

Athens is the capital of Greece and the site of an ancient city-state that defined the classical age, leaving behind a heritage still visible today in monuments such as the Acropolis. In his book, Athens: City of Wisdom, journalist and author Bruce Clark presents an exhaustive overview of the city’s distant and recent past, including periods of its history that are often overlooked.

Bruce Clark is an international news reporter from Northern Ireland. He studied Philosophy and then Social and Political Sciences at Saint John’s College, Cambridge, graduating with a BA in 1979. His first collaboration was with the Reuters News Agency, of which he became the main correspondent in Athens in 1982. He has worked as diplomatic correspondent for the Financial Times and Moscow correspondent for The Times (1990-1993); since 1998 he has worked mainly for The Economist, writing about international affairs, culture and religion.

Due to his postings, he is fluent in Modern Greek and has a good working knowledge of French and Russian. He has served on the Committee of the Maghera Historical Society and has participated in global debates organised by the Ecumenical Patriarch on the subject of faith and the environment.

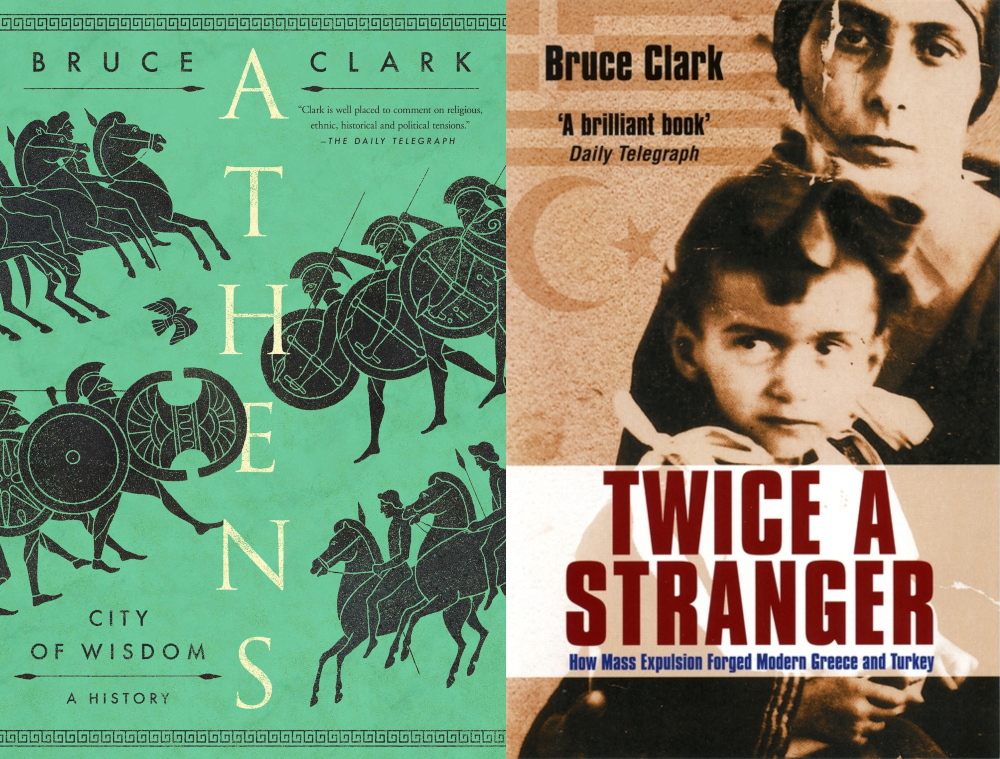

He has written the books An Empire’s New Clothes: The End of Russia’s Liberal Dream (1995, Vintage Paperbacks) and Twice A Stranger: How Forced Migration Forged Modern Greece and Turkey (2005, Granta [UK] 2007 & Harvard University Press [US]); the latter is a history of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey which took place in the early 1920s following the Treaty of Lausanne, for which he was honoured with the 2007 Runciman Award, the annual literary prize established by the Anglo-Hellenic League.

Athens: City of Wisdom (2021, Head of Zeus [UK] & Pegasus Books (US]) met with enthusiastic reviews; Professor Roderick Beaton has called it “a magnificent tour de force”, while writer Sofka Zinovieff has commended the author’s sensitivity to details. According to the Financial Times review, “Clark’s affection for a city that he still sees as a symbol of democracy is unmissable and highly informative”. In January 2022, Athens: City of Wisdom was longlisted for the 2022 Runciman Award.

Greek News Agenda interviewed* Bruce Clark on his latest book, his connection to Greece, and his view on matters such as the changes that Athens has undergone over the years, the way Asia Minor refugees have influenced the city’s character, and the reunification of the Parthenon marbles.

What was your first encounter with Greece? What was it about this place that spoke to you?

What was your first encounter with Greece? What was it about this place that spoke to you?

My parents took me to Greece on two family holidays – we made a road trip from Dublin to the Peloponnese when I was 11 and two years later we sailed round the Cyclades in an old wooden yacht. Then when I was 17 I came and lived in Athens for several months as a penniless wanderer. Since childhood I have felt a strange affinity with the Greek language, both ancient and modern.

Parallels have often been drawn between the Greek and Irish people. Greek News Agenda has repeatedly featured interviews with authors and scholars from Ireland and Northern Ireland – such as Richard Pine, Kathryn Baird and Theo Dorgan– who find many similarities between the Irish and Greek psyche. Do you share this view?

I think Ireland and Greece are both places where you can find a happy co-existence between modern and pre-modern ways of life and thought. By pre-modern, I mean that people in both countries feel a natural and unforced connection with the past through oral history, epic poetry and mythology. Among writers from Ireland who have formed a bond with Greece, I especially admire Seamus Heaney, who grew up not far from me, and Louis MacNeice, who grew up near Belfast and worked for the British Council in Athens in the 1950s.

Why is it that you chose to write a book on the history of Athens?

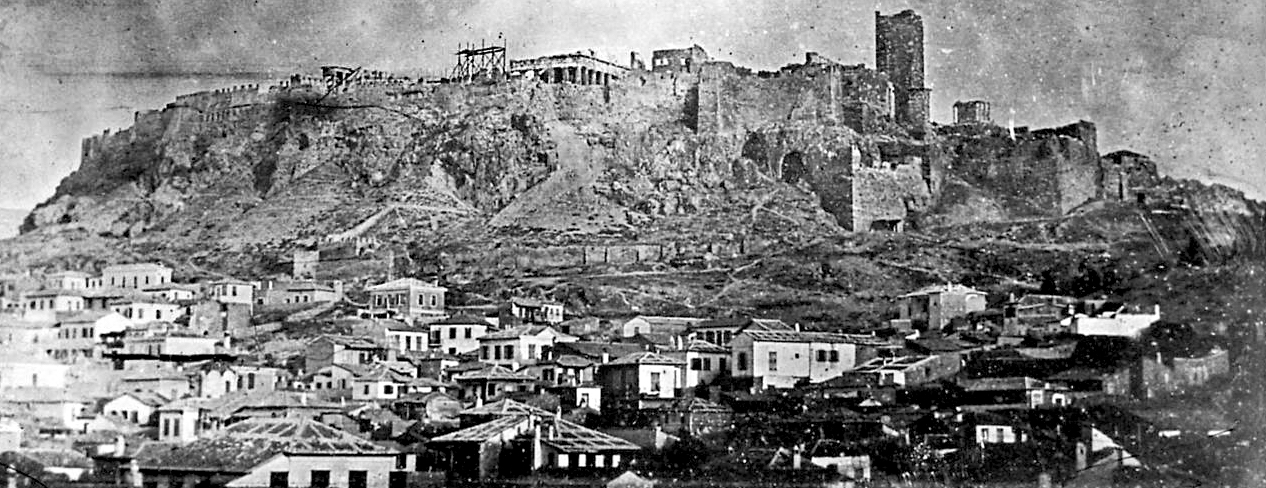

I felt there was a gap in the market. Long but readable histories of other ancient cities such as Rome, Istanbul and even London have been written but as far as I could see there was no exact equivalent for Athens. Many histories of Athens have jumped from the Periclean period to the modern Greek kingdom, and I felt there was a need to look at the intervening Byzantine and Frankish and Ottoman periods and see the points of continuity and discontinuity. Even in periods when Athens itself diminished to little more than a village, the Acropolis never ceased to be a place of spiritual and strategic importance. That important fact gives a certain coherence to the story of Athens, as I hope I was able to make clear.

View of the Acropolis and the Anafiotika neighbourhood, 1842, by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (1804-1892)

View of the Acropolis and the Anafiotika neighbourhood, 1842, by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (1804-1892)

Will it be published in Greek soon?

I very much hope it will be published this year. The rights have been bought by a distinguished Greek publishing house and I look forward to working with them.

How much has Athens changed since you had first arrived here as a Reuters correspondent? Would you say that it has changed for the best, or are there things you miss from those times?

The infrastructure and transport system have vastly improved, thanks to the metro, the Attiki Odos motorway system, the suburban railway and so on. The city is far more cosmopolitan, and Greek culture has been combined in other cultures in interesting and innovative ways. But the Athens that I first knew was a series of cosy, small villages where the population seemed relatively stable – there were tavernas and even kiosks which seemed to have kept by the same family forever. I miss that sense of cosiness, although it hasn’t completely disappeared.

Although your book concerns the history of Athens, it reads as an abridged history of the Greek nation; is this because Greece’s history, especially as a modern state, has been inextricably linked with this city? Is Greece too centred on its capital, compared to other countries?

Indeed, over the last 200 years it is hard to separate the history of Athens from the history of Greece and Hellenism. It could be said that over those two centuries the role of Athens gradually changed – from being a place that was symbolically vital but of marginal economic and demographic importance into a city that served as Hellenism’s vast, indispensable hub, and threatened to eclipse all other places. But that may be changing.

One of the unexpected and perhaps benign side effects of the economic crisis is that in a steady trickle, talented young people have settled (or simply remained) in “provincial” places and found innovative ways to make a living – by producing organic food or unusual tourist products. I hope that trend will continue.

The left hand group of surviving figures from the East Pediment of the Parthenon in the British Museum (by Andrew Dunn via Wikimedia Commons)

The left hand group of surviving figures from the East Pediment of the Parthenon in the British Museum (by Andrew Dunn via Wikimedia Commons)

In your book, you also touch on the subject of the reunification of the Parthenon marbles, of which, as you note, UK’s current PM was a strong advocate as a Classic student. Do you believe that the momentum now building for the marbles’ repatriation will lead a historic decision – seeing as even The Times has now shifted its editorial position on the issue?

I very much hope that will happen. I think the reunification of the Parthenon sculptures in Athens would generate an enormous amount of goodwill in both countries, and generally improve the level of public awareness of ancient Greece in Athens, London and elsewhere. Certainly the climate of opinion in the British establishment is shifting and that is a positive sign.

In Athens: City of Wisdom, you also cover the relatively unknown period between the city’s classical age and its establishment as the capital of the independent Greek state in 1834. Is there some specific instant or aspect of this period which you think would be particularly interesting or surprising for people to find out?

One of the great surprises was learning more about the life of Saint Filothei who is considered the patroness of Athens. She was not a remote or shadowy spiritual figure, but a very real personality of 16th century Athens who used her status as a nun to offer shelter and sometimes escape to women who had been cruelly treated. This made her unpopular with the Ottoman authorities and also probably with the Greek Christian men of the city who saw her as a disruptive element. Her worldly name was Revoula Benizelou. She deserves to be admired as a secular heroine as well as a saint. Bandits, presumably in the pay of some dark forces, attacked her convent and left her with fatal injuries. So she can be described as a martyr.

Another subject you cover in your book is the great challenge of managing the influx of refugees who arrived after the Smyrna disaster and the population exchanges stipulated by the Lausanne Treaty; to what extent has the history of the city been shaped by this massive shift in its demographics?

Another subject you cover in your book is the great challenge of managing the influx of refugees who arrived after the Smyrna disaster and the population exchanges stipulated by the Lausanne Treaty; to what extent has the history of the city been shaped by this massive shift in its demographics?

I would say that the effects of this influx are still very palpable in the demographics and culture of the city. The so-called refugee settlements (for example, Kokkinia or Nikaia in the Piraeus region, Virona or Kaisariani) have certain distinctive characteristics. These characteristics are an unusual mixture – a high left-wing vote, and strong church communities. As Renee Hirschon discovered in the 1970s, refugee culture can also combine a sense of grievance and loss with a strange sense of cultural superiority, a feeling of being heirs to a more sophisticated urban culture than that of the native Greeks. All these paradoxical characteristics reflect the traditions of Asia Minor Greeks who had to govern themselves and protect their collective interests in the turbulent world of the late Ottoman Empire.

Greek and Armenian refugee children near Athens in 1923, following their expulsion from Turkey (from the United States Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons)

Greek and Armenian refugee children near Athens in 1923, following their expulsion from Turkey (from the United States Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons)

You have written more extensively on the subject of population exchanges in your previous book Twice A Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey. In light of the upcoming 100-year anniversary of the Smyrna catastrophe, what lessons can we learn from the way that this issue was handled by the Greek government of the time, and the role that the League of Nations played in it?

Let’s separate the Smyrna tragedy itself from the story of the long-term settlement of the refugees. I think the Smyrna tragedy itself was exacerbated by the callous behaviour of the Western governments whose navies were reluctant to rescue the Ottoman Christians who were fleeing for their lives. Even the Greek government was slow at first to send ships to evacuate its own ethnic kin.

Once the refugees arrived in Greece, I think their resettlement over the next ten years or so can, on balance, be described as a success story – although it was a success which involved great material hardship and psychological pain. The Refugee Settlement Commission, established by the League of Nations, was a relatively efficient bureaucracy which drew on the services of talented American, Britons and Greeks. Hundreds of thousands of people were settled on farms in Greek Macedonia and began working productively. Perhaps the key factor was that, despite all the arguments over the perceived political affiliations of the refugees, getting them resettled was understood to be a matter of national survival. If resettlement had not succeeded, the Greek state and society might have been in danger of collapsing.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi; photos of Bruce Clark courtesy of author

Read also via Greek News Agenda: BOOK OF THE MONTH: ‘The Eye of the Xenos’ by Richard Pine with Vera Konidari; Richard Pine on Greek-Irish Encounters; Theo Dorgan on the Myth of Orpheus Amid Greek-Irish Encounters; POEM OF THE MONTH: “Impression de Voyage” by Oscar Wild