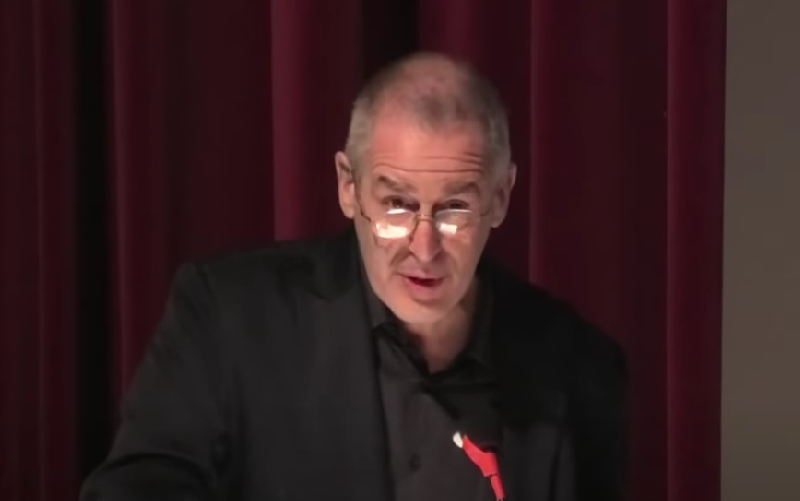

Prominent British historian and award-winning author Mark Mazower, was officially sworn in as a Greek citizen on Monday, in recognition of his “promotion of Greece, its long history and its culture to the international general public.” The Ira D. Wallach Professor of History at Columbia University in New York City specializes in Balkan and Greek history, and has written a number of books focusing on events in Greece during the 20th century.

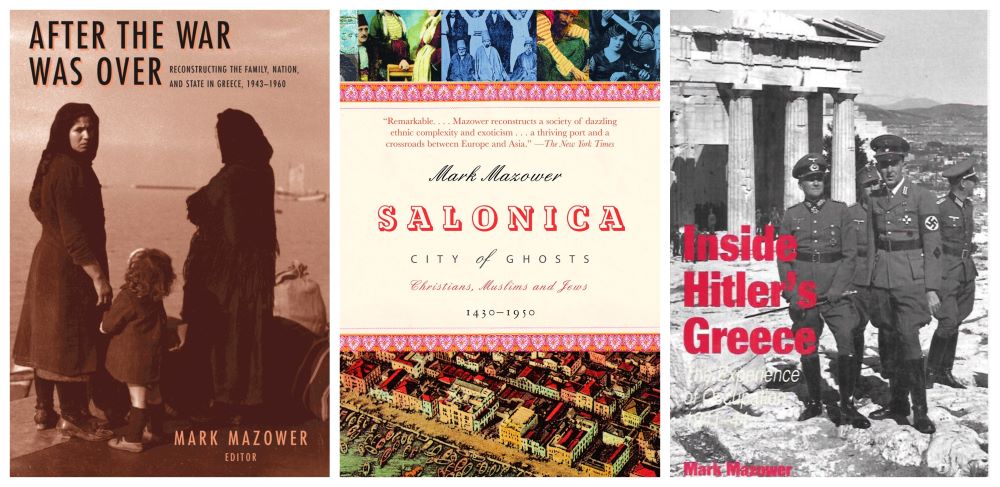

These include the titles “Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44“, “After the War was Over: Reconstructing Family, Nation and State in Greece, 1943-1960“, “Dark Continent: Europe’s 20th Century“, “The Balkans”. His latest book, “The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe” is an important new history of Europe’s first national uprising, the Greek War of Independence and has been chosen as one of the top history books of 2021 by The Economist.

Among his award-winning books on Greece are also “Salonica City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews, 1430-1950” which received the Duff Cooper Prize in 2005, while he has received both the LA Times Book Prize for History and the Trilling Award in 2009 for his work “Hitler’s Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe“.

Mazower has also supervised a number of research papers and revived interest in Greek studies abroad, while his op-eds on historical and current affairs issues are regularly published in the media.

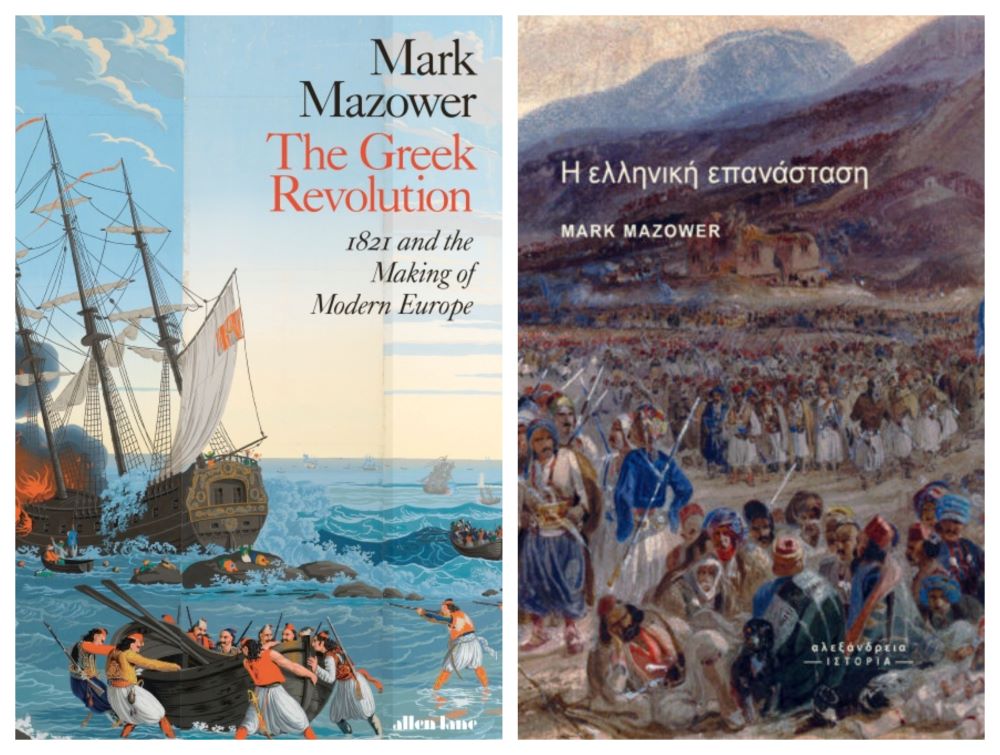

The decision to award the historian with the Greek citizenship was announced last September, but Mazower chose to attend the ceremony last week Athens, during his visit to the Greek capital for the launch the Greek translation of his new book “The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe” at an event at the War Museum.

Launch of the Greek Edition of “The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe”

Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis hailed the work of Mark Mazower on Greek history in his videotaped address for the presentation of the Greek edition of “The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe,” saying the historian has been devoted to “firmly placing Greek history in the greater context of the history of Europe.” Mentioning that the historian became an honorary citizen of Greece, the premier said that Mazower’s recent book,” will contribute to Greek historiography and will prove a landmark in the Greek people’s diligent search for national self-awareness.”

In his own address at the launch of the Greek translation of his book, Mazower thanked his publishing house Alexandeia in Greece, the translator Nikos Kouremenos as well as “the extraordinary fellow historians 1821 who have been and continue to transform our understanding of the subject” adding that “this book could not have been written without the articles and the conference proceedings, the books and the dissertations of the previous 50 years”.

Mazower went on say that while “it’s fair to say that the Junta more or less killed serious interest in the historiography of 1821 for quite a long time”, in the 1990s there started “a wave of new, extraordinary research”, specifying that “the sheer volume of high-quality research that has been produced in Greek over the last 30 years has been absolutely extraordinary”. He added that furthermore, in comparison to other countries, “Greece is now blessed with one of the most sophisticated, diverse, and cosmopolitan, polyglot community of historians anywhere in the world. Greece is fortunate in her historians, has nourished them with a deep popular attachment to history and will, I hope, continue to support them in the years to come.”

Speaking on the subject of his book and the history of 1821, Mazower mentioned that “an extraordinary amount of research is in the works and will be published in the years to come. I shall be happy if my book is read as an invitation to explore some of the key areas that we still know too little about.”

One example of an area that has yet to be researched, according to the historian, is the war from the side of the Ottomans: “The Greeks won eventually, but that means that the Ottomans lost. How did the Ottomans lose? How did the Ottomans come to lose such an apparently favorable situation? I think it’s fair to say that we don’t have any idea. And we won’t have any idea until we know a lot more out of the Ottoman archives than we do. Actually, the first serious volume of documents from the Ottoman archives was published by Brill in this past year, a thousand pages long and it’s publicly available. We are going to start knowing a lot more about the Ottoman side, and therefore about the Greek story as well.”

For a second example of research areas yet to be explored, Mazower turned to the cover of the Greek translation of his book, a picture by Theodore Leblanc, a Frenchman who was both a trained artist and a trained soldier. The watercolor, titled “Greek soldiers during the insurrections of 1829” has been preserved at the Brown University Library in the United States. A specific segment of the painting was chosen as a cover of the book an the reason why, as Mazower pointed out is because, “if you look at it, you see that great range in Greek society that actually underpinned the victory of 1821, but is very rarely analyzed. You’ll see down at the front two or three rather old men, one of them is leaning on his elbow, you will see in the far right, a little child. This is all a part of the army. You’ll see a dog. You’ll see some African soldiers who have escaped from Ibrahim’s army. You’ll see above all the great mass of the villagers and the peasants of the Peloponnese. How did they get to that point? How did they survive for 4 or 6 years? Who had fed them? We know very very little about this absolutely fundamental aspect of 1821. We have much more to learn and I look forward to what future historians will uncover.”

The Greek Revolution and the Making of Modern Europe

Mark Mazower´s “The Greek Revolution and the Making of Modern Europe” was published this September, receiving international critical acclaim, form publications such as the New York Times, The Times Literary Supplement, the Times and the Economist, among others. In the introduction of his book Mazower writes: “The uprising of 1821 came near the end of a half-century of revolutions. The epoch of global transformation had begun with the United States successfully shaking off colonial power and it continued with the French overthrow of their monarchy and Haiti’s bit for freedom. As the Greeks rose up, the Spanish colonies in South America were fighting for independence and much of southern Europe was in turmoil. The American independence movements had the advantage of being an ocean’s remove from their oppressors, but the European revolutionaries were not so lucky and uprisings in Spain, Sicily and Piedmont were easily suppressed. Only the Greeks fought on and, against all odds, prevailed.

What they accomplished thereby was unique, not merely eradicating the power of the Ottoman state in their lands, abut also sweeping away the entire ruling philosophy and the institutions that had supported it. Not the legitimacy of dynasties, but nation, faith, capitalism and constitutional representation were the watchwords of this new order. The fundamental principle, wrote Lord Acton in his 1862 essay on ‘Nationality’, was that ‘nations would not be governed by foreigners’: it was this principle that marked the Greek war out of the other revolutions of southern Europe and helps explain why it was sustained and widespread, but also unusually brutal and violent”.

Mazower elaborated further on the place of the Greek Revolution in the “Age of the Revolution” in his recent interview with Markos Kaisarinis for newspapter “To Vima”:

What are the bridges connecting the American Revolution of 1776, the French Revolution of 1789 and the Greek Revolution of 1821?

If you look at the celebrations, say for example, on the 150th anniversary of 1821, you will notice that the emphasis was on the uniqueness of the event of the Revolution, there was no talk of an event with international ramifications. This is how many generations of scholars viewed the Greek Revolution, up until recently. So, something has changed in the recent years, that has made appealing the framing of Greece, and of 1821 in particular, in a global context. This approach is not novel, however the extent of its acceptance, is. Therefore, the question is, what we are gaining and what we are losing by adopting this perspective. I believe that we gain a lot. Now, the prevailing sentiment is that the war for Greek Independence is a part of the whole revolutionary period between 1789 and 1848, at the epicenter of which were the Napoleonic Wars.

This is how its contemporaries perceived it as well. Today, from our distanced point of view, we can see as well just how radical these changes were of world history. The idea that democratization was viable. The idea that the will of the people could overthrow empires. The political ideas of the Enlightenment. So, all those who participated in the Revolution of 1821, saw themselves in that world. Then, just like now, Greeks were conscious of the international environment. After all, it the international factor was the reason that 1821 had a victorious ending.

What we might lose, or maybe overlook, by adopting this perspective of the Greek Revolution of 1821 as a part of the Age of Revolutions?

It is true that the Greek Revolution was the first revolution that mobilized a society and produced a nation-state, a process that became the rule internationally. But we forget that this didn´t happen immediately. On the contrary, many thought that it was an exception – an exception that should not be repeated. The Greek case was therefore a controversial phenomenon. What is more, there were special and unique factors that differentiated what happened in Greece from movements of the same era in Sicely, Spain or Portugal. Two differentiating factors stand out for me: firstly, the particular social structures of Ottoman Peloponnese and Roumeli. Secondly, the complex role of religion and of the orthodox clergy – but also of the Patriarchate. The Patriarchate didn’t seize to exist [after Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople Gregory V was hanged by the Ottomans in 1821]. The successors of Gregory V maintained their influence on the Greeks.

I.L.

TAGS: HERITAGE