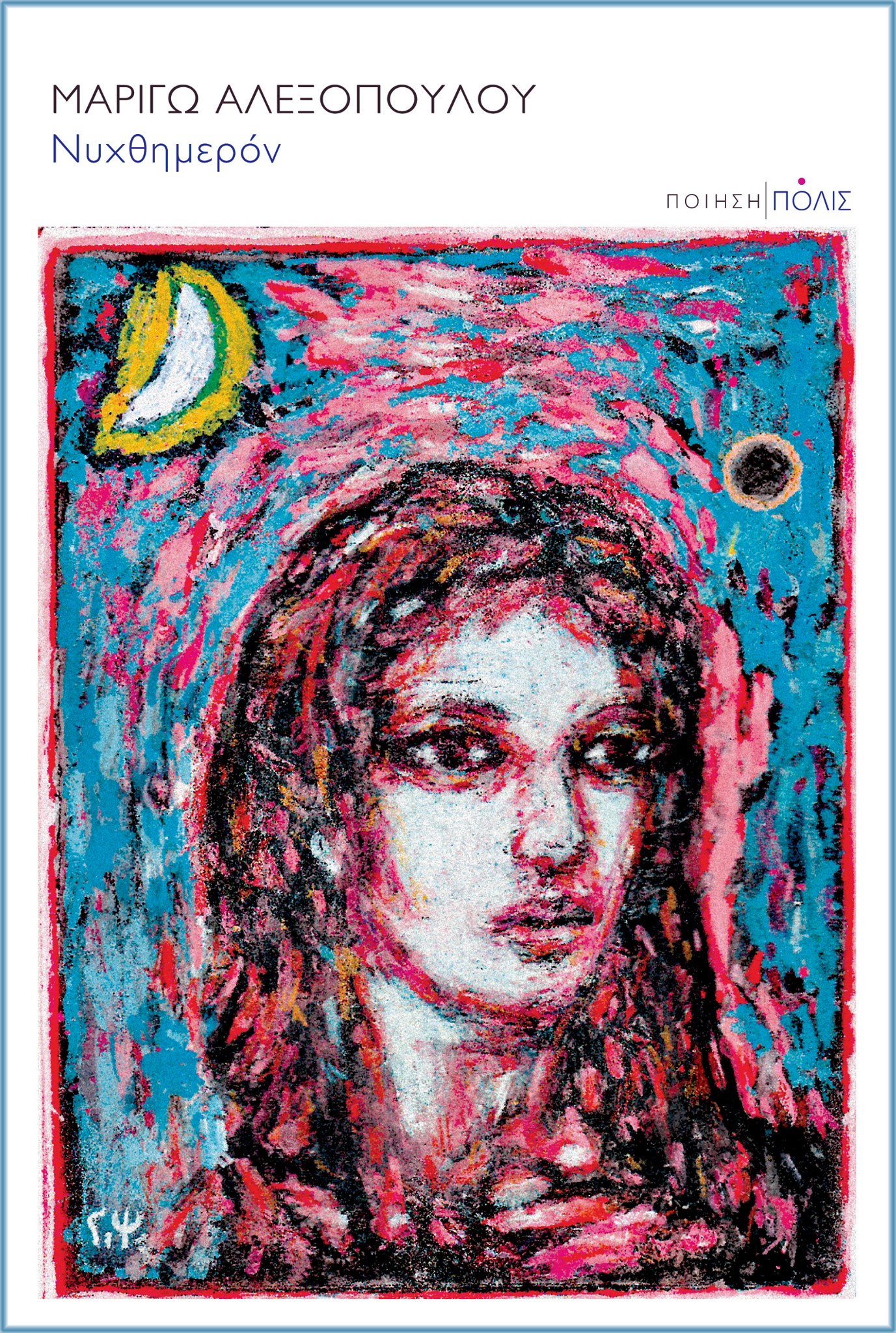

Μarigo Alexopoulou (1976) has published seven poetry collections: Faster than Light (2000), Which day is missing (2003), The Envy-meter (2006), The stars move in line (2008), The era before remedies (2012), The Blue book (2015), Night and Day (2020), and the monograph The theme of returning home in ancient Greek literature: The Nostos of the Epic Heroes by Edwin Mellen Press. She has recently developed a research interest in ancient Greek theatre and the ancient Greek epigram. She runs the website poetry cafe. She is a teacher at Moraitis School.

Your latest poetry collection Night and Day was recently published by Polis. Tell us a few things about the book. What about the title?

My new poetry collection, Night and Day, comprises 41 short poems divided in four parts. The first part is dedicated to the brother, in the sense of the brother of the former, who haunts us as we grow up. In the second part, in children-mothers, there are images related to the first childhood memories in the shadow of adults. In the third part, landscapes are transformed into sea landscapes with a nautical terminology. The naval term ‘Avast’ is the title of the last part of the collection, my personal inner call to show patience. As if to say: “Hold on tight”. The poems of the fourth part were written during the quarantine and thus “Avast” is something each one of us address to himself/ herself as he/she experiences the pandemic conditions. The title constitutes the essence of the collection. You work night and day. You stay awake with the same thoughts night and day. You think night and day in a poetic way.

Memory, reminiscence, a feeling of nostalgia about what is forever gone seem to be central to your latest poetic venture. How is the past interweaved with the present in your poetry?

Night and Day has mental landscapes and memories as its binding thread. It is the meeting of my verses with my inner images. The poems represent this meeting, as it appears on the cover of the book illustrated by Yiannis Psychopedis.

In the poems of the book, you converse with historic and literary figures of the past. What purpose does this conversation serve?

Ι was more than lucky to associate with poets I loved and who loved me back (Yannis Kondos, Mathaios Mountes, Christoforos Liontakis, Kostas Papageorgiou etc). This intercourse defined me because it is how a – initially invisible – workshop of words started to operate inside me. In my last poems there is a symbolic connection with women of my place of origin, such as Manto Mavrogenous and Melpo Axioti, but not only (Emily Dickinson), on the basis of their inherent revolutionary spirit against the official ‘made-dominated’ society.

“Every word is a story […] The poetic windows are open as long as you swim with the words and do not feel hooked”. What role does language play in your writings?

Our (true) homeland is language, as it becomes evident in the poem titled Dream: I saw my family deeply rooted/ in words. Language constitutes the primary foundation of our existence. It’s through the accuracy of words that purification in human relationships is achieved.

From your first poetry collection Faster than Light to Night and Day twenty years later, what has changed and what has remained the same in your poetry? Are there recurrent points of reference in your books?

There is Vladimir, the leading figure in my poem “Thief” in my first poetry collection, who has since haunted my next books of poetry like a fairytale-like (comforting) element, as mentioned in the poem I dedicate to Vladimir titled “The kiss of life”, from my collection Which day is missing: I left you/to take your final breath/ and I was left/ with the doubt/that I could/ have saved you.

This hope of realization runs through all my poetry collections. On this journey from my first collection to Night and Day, I was often tempted to deny what I loved, poetry itself. This is how the following verses in my last collection were written: I leave poetry behind / and what abyss awaits me ahead, where there is the feeling that we should put our trust on poems and let them, boldly and without fear, lead us – possible to the end of idealization and thus to the end of the frightful fear of the impossible.

“Homeland is not only ‘nostos’, a yearning for home, but also the union of many different tiles preserved by language, aesthetics and the values of each one of us […] In other words, homeland is a spiritual reunion“. Tell us more.

‘Nostos’ in the sense of repatriation is not only achieved by returning to homeland but by reuniting oneself with all the spiritual elements that define our identity. Our language, our values and principles, as well as our aesthetics are part of ourselves that ultimately define the boundaries of our world. As Professor Angelos Chaniotis eloquently put it, the Parthenon marbles should be reunited and not returned.

“When you get out of there / will your face be the same?” you write in the poem “Quarantine”. Does poetry offer a creative way out in times of a pandemic?

In the most difficult of times, poetry stands as an indispensable companion with the absolutely necessary. A companion which safeguards the elements of a world that is familiar and at the same time enigmatic. As poet Tassos Livaditis writes: “And poetry is like climbing an/ imaginary ladder to cut a real rose”. Poetry, therefore, constitutes a rare lesson of vigilance and perseverance since it helps to transform the evening kitchen noises into fantastic paths.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*ΙΝΤΡΟ ΙMAGE: © Charis Papadimitrakopoulos

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE