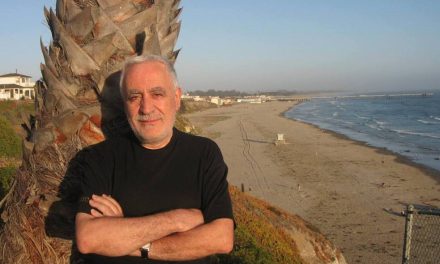

Writers Thanassis Giohalas and Zoi Vaiou open a window to 19th century urban life with their latest book “Athens in the 19th Century: Images of a Journalistic Travelogue” (‘Η Αθήνα τον 19οαιώνα, Εικόνες μιας οδοιπορίας μέσω του Τύπου‘). Using as a tool news items of the era’s press, the authors trace the orgin story of a burgeoning city though the microhistories -as well as the crimes and misdemeanors- of its inhabitants.

The authors, who have a degree in History and Archeology from the University of Athens and are secondary school teachers, have spent several years of their lives researching and collecting material on the history of the Greek capital. As part of their joint work, they have also published in 2006 a collection of personal and classifiede ads published in Athenian newspapers from 1833 to 1940. Greek News Agenda* spoke to Thanassis Giohalas and Zoi Vaiou on the transition of Athens from an Ottoman city to a European capital, the visible traces of the past on today’s city and finally, on the characteristics of nineteenth century newspapers.

Nineteenth century Athens was the new capital (1834) of a new state, with only 30,000 inhabitants. It was the Athens of King Otto and Ernst Ziller, neoclassical mansions and glorious balls, but also rock fights, beggary, a non-existent water-supply network and daily clashes, both large and small. How was the daily life of an Athenian at the time?

As the capital of the newly created Greek state, it took Athens several decades to become that which her role required. The small town, with the few thousand inhabitants gathered at the foot of the Acropolis, in the old neighborhoods of Plaka, Psyrri and Monastiraki, would expand and incorporate in its urban fabric new neighborhoods and multiply its inhabitants.

The daily life of the people of the city varied, in accordance with their financial situation and social status. The misery and difficult livelihood of the poor narrowed their movements to the confines of their neighborhood, where everyone knew each other and developed relationships based on solidarity, but there was also competition, envy and bitter yarns; “poverty breeds discontent”, notes the age-old truism.

Conversely there is the daily life of the emerging bourgeoisie, with its social life evolving within luxurious mansions that were built, in principle, around the Palace. Road construction projects, the continuous reconstruction with public buildings and residences, as well as the operation of the University combine to attract many foreigners and people from the country to Athens, who settle in new neighborhoods, such as Naples, dynamically altering Athenian society.

Everyone moves at will in the capital. There are no watertight and restricted areas. Luxury carriages move alongside carts and work animals, and European attire is worn alongside the fustanella and traditional local women’s outfits.

Thus the daily life of Athenian residents follows different trajectories, which, however, converge in the heart of the city.

The diverse anthropogeography of 19th century Athens does not necessarily refer to cosmopolitanism. During the Regency period (1833–1835), i.e., before the coming of age of Otto, Bavarian engineers, workers, members of the military and merchants were added to the native urban population and gradually many of them were integrated and became Greek.

The know-how for the construction of the road network was, as expected, imported, and brought to the young capital French engineers, who it seems were especially liked by Athenians.People looking for an opportunity to make some money, as well as various offenders, Greek and foreign, flocked to the city where everyone at first felt welcome. It was no surprise that the Maltese made their way there, given their standing presence in cities of the Eastern Mediterranean, while Persian shoeshines –for reasons that are not clear – appeared in the area of Chafteia in central Athens, competing with local fellow-craftsmen.

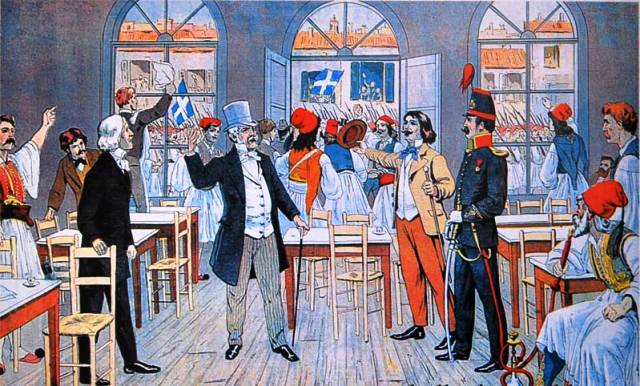

At the same time, in the luxurious cafes and hotels of the city centre (Omonia and Syntagma Squares) the educated and multilingual bourgeoisie as well as foreign residents were informed by both Athenian and foreign press. Bilingual newspapers catered to this readership, which they facilitated and flattered. The arrival of Greeks from communities abroad (Romania, Egypt, etc) contributed ostensibly to the creation of a cosmopolitanism, which, however, was far from that of Izmir, Constantinople or the European capitals, in terms of quality and quantity.

It is mentioned in the preface that the urban planning, the creation of new infrastructures and the establishment of public institutions in the city sought to detach the capital from the embrace of the East and to push it dynamically towards the West. Whatwerethemostimportantstepsinthatdirection?

The European orientation of the new capital has been evident since its inception. The romantic spirit of the time combined with the ancient glory of the city served as the foundation for the construction of modern Athens. The Ottoman past was to be forgotten because it functioned as a brake to future progress.

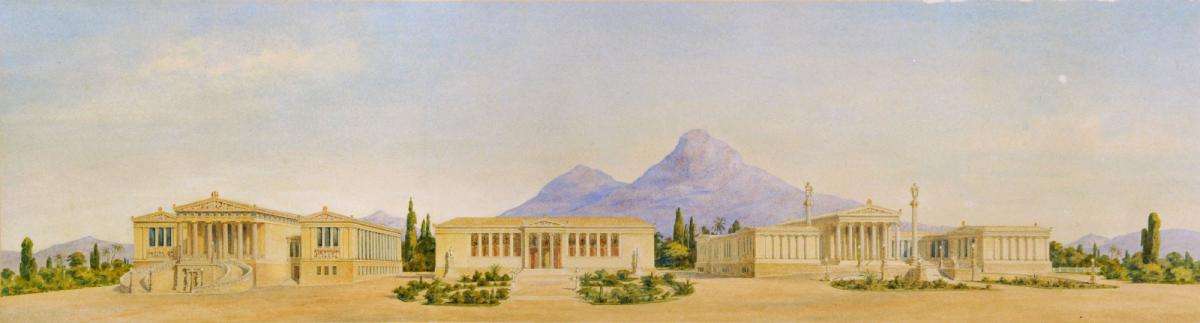

The original urban plan for Athens by Cleanthes and Saumbert envisioned a neoclassical city with boulevards, squares, groves, monumental buildings and gardens. However, the plan’s implementation cost (mainly due to the necessary expropriations) rendered it inapplicable. Thus it was the Klenche plan that was adopted, which was considered more realistic but that too suffered cuts and alterations. Despite the inherent weaknesses of the Greek state (financial difficulties, lack of organization, political unrest) the European facade of the capital was evident by the end of the 19th century.

The investments and donations by rich expatriates who repatriated and the private initiative of merchants and businessmen fill the centre of Athens with imposing mansions, luxury hotels and cafes, and European standard shops. The issue of road dust and mud however was not dealt with until the beginning of the 20th century with the asphalting of many highways, whilst water supply and sewerage problems would be dealt with much later.

The people of Athens embraced change with surprise, admiration, optimism or skepticism, ambivalence and caution. Europe, the West, is no longer so distant and foreign, but will take time to become familiar.

The newspaper clippings you have chosen are very humorous, both on account of the situations described and because they come from satirical newspapers, a genre that is almost extinct. Was it a time of “innocence” and “naivety” of the Athenian press?

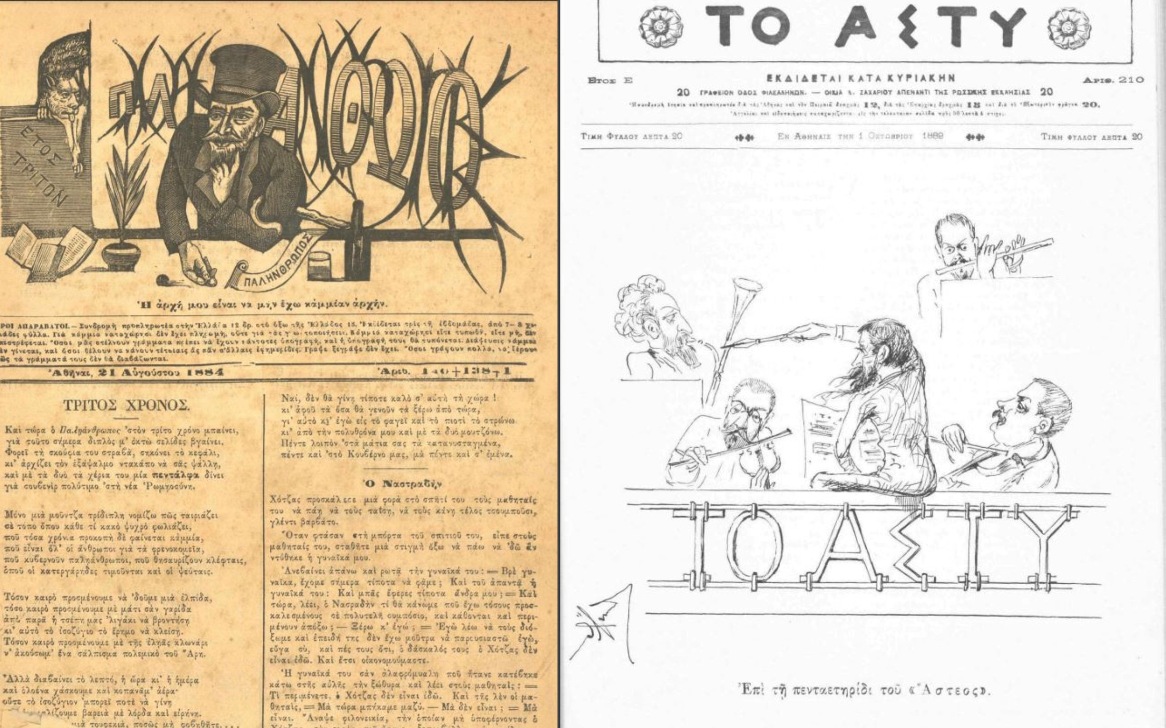

Satirical publications appear as early as the 1840s, but they increase and multiply from the 1870s to the end of the century. Indicative titles include: Rambagas, Palianthropos (Scoundrel), Aristophanes, Asmodeus, To Asty (the City), O Romios (the Greek). As is obvious from their enviable circulation, they are addressed to a wide readership which enjoys their sharp wit. Satire enjoys exaggeration and the grotesque.

Using humor as a vehicle, they targeted political wrongdoings and bad management by their respective rulers, leaving no room for flattery and embellishment, but only for political points of view. Such denunciatory writing expressed public opinion, and imaginative editors operated as mediators between citizens and the state.

They are by no means “innocent” or “naive”, but they are certainly enthusiastic, resourceful and often extreme.

We would like to thank our friend Lina Louvi, Professor of History at Panteion University, for kindly providing us with her private collection of 19th century satirical publications, which enriched our resources and facilitated our research.]

Are there any traces (architectural or other) of 19th century Athens today in the city?

Modern Athens “took care” to erase many of the traces of its childhood and adolescence. The legitimate or not needs of the big city led to the unforgivable destruction of emblematic buildings of its past. What has been rescued offers relief and exaltation to travelers and sightseers and helps us to recreate, albeit in fragments, the capital’s image in the 19th century.

The Schliemann Palace (Numismatic Museum), the Catholic Cathedral, the Athens Eye Hospital, the quintessential Athenian neoclassical trilogy (the National Library, the National University of Athens and the Academy), the Serpieri Mansion, the house of D. Soutsou – D. Ralli and the Arsakeio are the neoclassical architectural landmarks on Panepistimiou Street. The old Royal Palace (Parliament) with the adjacent Royal (National) Gardens and the Zappeion mansion in the wider area of Syntagma square, as well as the Panathenaic Stadium (Kallimarmaro) that serves as a perpetual reminder of the first Olympic Games in 1896, define the city’s important historical centre. Finally, the Polytechnic and its neighboring National and Archaeological Museum mark Patision Street.

These 19th century architectural impressions are not lifeless shells. They participate in the social, political and spiritual life of the city. Today, visitors and passers-by see and perhaps immortalize their presence with their camera or they may simply pass by in a hurry and indifferently.

Athens has changed. People have changed. But there are streets and squares where the city’s inhabitants gather to celebrate or demonstrate, following the invisible traces of a time past that meets the present and heads towards the future.

* Interview by: Ioulia Livaditi and Lina Syriopoulou

** Translation by: Magda Hatzopoulou