George Petrides, who lives and works in New York City and Athens, Greece, creates abstracted figurative sculpture. Born and partially raised in Greece, he has always been inspired by ancient Greek sculpture but also by the later works that were influenced by it from classics such as Donatello, Michelangelo and Rodin to modernist and contemporary sculptors such as Charles Ray and Huma Bhabha.

He is concerned with the human experience in the form of the body and the head, exploring the beauty and the imperfection of people and of life.

Growing up in a family of artists and business people, he made and studied art through

college, then took a detour to Wall Street, continuing to study and make art part-time. For over 20 years, off and on, he took drawing, painting and sculpture classes at the New York Studio School, at the Art Students League, and at the prestigious Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. Since 2017 he has dedicated himself to making art full time. He has had solo exhibitions in Dubai, Monaco and Mykonos, and group exhibitions in Athens, London and New York.

Recently, Petridis’s work was showcased at a two-artist show Figure and Form, hosted by the Consulate General of Greece in New York, where his figurative sculptures were paired with the abstract Pixel Field paintings of Greek-born American artist Nassos Daphnis (1914-2010).

The artist’s latest work is a series inspired by the centennial of the Destruction of Smyrna in 1922 and last year’s bicentennial of the Greek Revolution: the Hellenic Heads are Petrides’s “personal exploration into his Greek background”, and they encapsulate the influences that have shaped him, drawing from six important periods in Greek history: the Classical Period (510–323 BC), the Byzantine era (330–1453 AD), the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), the Destruction of Smyrna (1922), the Nazi occupation and Greek Civil War (1941–1949) and the Present.

The eight works will be presented in a traveling exhibition, which is going to be hosted at the Embassy of Greece in the U.S.; it will be on view in the Embassy’s exhibition space on weekdays from May 9 to June 10, 2022 (11:00am to 3:00pm, closed on May 16,17). With the aid of the Public Diplomacy Office at the Embassy, Greek News Agenda interviewed* George Petrides ahead of the upcoming opening; the artists spoke about his influences, his working process and the place that his Greek heritage has shaped his artistic identity.

George Petrides with some of his Hellenic Heads; photo ©Simatos/Cadena

George Petrides with some of his Hellenic Heads; photo ©Simatos/Cadena

We understand the Embassy of Greece to the USA, in Washington DC, will host your Hellenic Heads series. Tell us about this work.

I’m honored to present my sculptures at the Embassy of Greece to the USA. As a Greek-American, to show at a prestigious venue that is important to both Greek and American life means a lot to me. I’m grateful to Ambassador Papadopoulou for inviting me and to Ms. Moutroupalas, Cultural Attaché, who worked with me to bring the exhibition to fruition. When I presented my work to them and to Mr Papadopoulos, Head of Public Diplomacy at the Embassy, I saw that they understood my work on many levels – historical, artistic, emotional. I am eager to bring the Hellenic Heads from my New York studio, and a few flown in from Athens, to Washington DC, for the exhibition running from May 9th to June 10, 2022.

The Hellenic Heads are a personal exploration of my Greek roots, through over-lifesize head sculptures that have been inspired by six important periods in Greek history spanning 2,500 years. This series is a vehicle for, and the result of, my search for the Greek influences that have shaped me and the people closest to me. I chose six periods in Greek history that could be deemed to have ongoing influence on contemporary Greeks: the Classical Period, the Byzantine Period, the Greek War of Independence, the Destruction of Smyrna (of which the centennial is this year), the Nazi occupation and Greek Civil War, and finally, the Present. I researched each period, considering artifacts, family stories, and historical photographs. I looked at sculptural precedents for inspiration in the major museums of the world, including Athens, New York, Paris and Rome. With these foundations, I created the sculptures which I hope you will see at the Embassy or at other venues to which the exhibition will travel, such as The Muses in Southampton, NY from June 16 to September 5, 2022.

The artist in his studio (Heroines of 1821 from Hellenic Heads); photo ©Simatos/Cadena

The artist in his studio (Heroines of 1821 from Hellenic Heads); photo ©Simatos/Cadena

What prompted you to make this body of work?

As a Greek-American –born in Athens and having spent more than half my life in New York City– I have always been engaged with, and sometimes overwhelmed by, my Greek roots. Starting from age 5 or 6, I was exposed to Greek antiquities by my aunt who was a tour guide to the Acropolis and the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Later, at Harvard College, I studied liberal arts, including Classical Greek literature, philosophy and history, as well as modern Greek literature, taught there by Professor Savvides, the translator of Cavafy and Seferis. Later still, I made four visits to Mount Athos, where I was steeped not just in the Orthodox faith but also in Byzantine art; I recall being dumbfounded seeing icons and relics more than a thousand years old.

With those foundations, I created over-lifesize portraits, the largest of which is 85 centimeters or almost 3 feet high. However, my portraits are not historical copies; they are personal interpretations. When I was sculpting Thalia, inspired by the Classical Greek Period, I looked not just to the piece of the same name in the Vatican Museums, but also to photos of my mother as a young woman in post-war Greece. When I was sculpting Archon, referring to the Byzantine Period, I looked not just to the colossal heads of Constantine the Great at the Capitoline Museums in Rome and The Met in New York, but also to photographs of my father as a young sea captain, working for Goulandris shipping interests, embodying leadership and clear vision ahead. For Heroines of 1821, I wanted to convey the strength, defiance and resilience of three female leaders in the War of Independence (Manto, Laskarina and the overlooked Domna Visvizi of Thrace), and found a modern Greek woman to sit for the piece, a woman with similar personality traits: My fiancé!

The artist in his studio (Thalia from Hellenic Heads); photo ©Simatos/Cadena

The artist in his studio (Thalia from Hellenic Heads); photo ©Simatos/Cadena

Your art is focused exclusively on the human body, particularly the head. Why?

I find my fellow human beings to be the most fascinating, difficult, and rewarding subject. Relationships are important to me in every aspect of my life, which is not to imply that I always succeed at them. I often experience an inability to understand or to connect, which probably drives my interest in figurative sculpting. As to the head specifically: It is the most human part of the human, the most expressive and the most difficult to convey and the most interesting when the conveyance succeeds.

I’m thinking of the title of the first book that came out on my work: The Beauty of Imperfection. I think that summarizes my views of our fellow human beings and of life generally: That there is beauty not in spite of but because of imperfections. Many of my pieces show imperfections, and I hope that you will perceive them as beautiful.

Some of your Hellenic Heads have been described as “dark”. Are they? Why?

Some, fortunately not all, are “dark” because they reflect the periods I studied. Studying the Destruction of Smyrna, including the experiences of my grandmother who survived it and the published diaries of her brother who fought in the war that preceded it, resulted in a sculpture conveying sadness of losing their homeland, but also dignity in accepting their fate and rebuilding their lives in a new country, Greece. To study Greece in the 1940s was to learn about my father’s time in an internment camp, to learn about the vibrant Sephardic Jewish community of Thessaloniki whose members were sent to Treblinka. Many of us are fortunate to have never directly had such experiences in our lives, but similar phenomena exist today, like in the daily lives of Ukrainians these past few months.

That said, the Hellenic Heads are presented as a unity, so these “dark” pieces are balanced by others that are “light”: The elegance and thoughtfulness of a classically inspired head, the strength and leadership of a Heroine of 1821, a young girl representing the Present, whose optimism reflects her future but also the optimism a nation and people might feel.

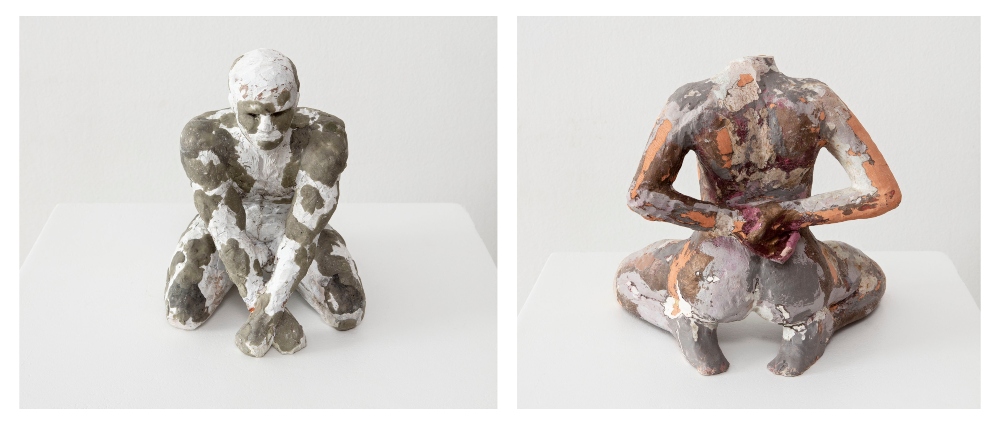

Boxer at Rest (Self Portrait), 2021; Tara Tronie, 2021 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)

Boxer at Rest (Self Portrait), 2021; Tara Tronie, 2021 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)

You seem to draw from many artistic influences. For example, we see echoes of Auguste Rodin in your work. Please discuss.

In the catalog essay, critic and curator Katy Diamond Hamer asks: “How does one look towards the past with a mirror, and still see something new reflected back? This is something that many artists face in their respective practices as it’s nearly impossible to not be informed of, or inspired by art history.”

I fully agree. I do not want to sculpt figures without engaging with the figurative sculpture that came before, starting with Mesopotamian and Egyptian sculpture and traveling over 8,000 years to contemporary figurative work. I believe many of these prior investigations into the human subject are relevant. Like Alberto Giacometti, I do not believe that there is “progress” in art, that contemporary art is somehow better than older art. I see many ancient, Renaissance, neoclassical, 19th century heads that are more compelling than what I see in the commercial galleries today.

Yes, Rodin is an important influence. I recall the awe I felt when I first saw his Gates of Hell, at Stanford University in 1992. To me, Rodin is the culmination of the Greco-Roman tradition of figurative sculpture. What started with the Archaic Kouroi and developed through the Classical and Hellenistic periods, was taken up after 1500 years in the Renaissance, expressed in new ways by Donatello and Michelangelo and later by neoclassical sculptors before Rodin came onto the scene in the late nineteenth century. After Rodin, there was a withering interest in the figurative, and the non-figurative “New Sculpture” emerged in the 1950s alongside Abstract Expressionism in painting. In recent decades there has been an enthusiastic return to figurative painting and sculpture, a prominent example being Charlie Ray, who makes extensive references to ancient Greek sculpture.

The artist with his tools; photo ©Simatos/Cadena

The artist with his tools; photo ©Simatos/Cadena

All of your Hellenic Heads are larger than lifesize. Some are nearly a meter tall. Why?

Jeff Koons has said that scale changes the way the viewer perceives the work, even if it is the exact same work, enlarged. I have found this to be true as I often do similar works in different sizes, and I can see how viewers react to each.

Acclaimed artist George Rorris, who is famous for representations of the human form, wrote that your sculpture reflects the “primitive sensuality” of your soul, “indomitable and unadulterated”. Would you say that true art originates in a primordial instinct, even though we often associate art with refinement and sophistication?

I have great respect for George Rorris, both as an artist–one of the most important working today not just in Greece but globally–and as a human being. I am honored that he wrote the essay that appeared in the book George Petrides: Recent Work 2019-2021 from which you quote.

As to his specific comments: I think he is correct, and expressed it more poetically than I could have. There are many kinds of art, ranging from the cold, conceptual kind to the emotionally-driven “primitive” and “unadulterated”, to use his words. I am happy to be closer to the latter end of that spectrum, for two reasons: First, it is who I am, and I believe in the saying, “Be yourself – everyone else is already taken”. Second, I think that the qualities that Rorris refers to have real power. I hope you feel that power when you see the Hellenic Heads.

Is there good art that is refined and sophisticated? Of course! There are as many different kinds of art as there are artists, and viewers must judge for themselves what speaks to them.

Age of Innocence (Nicole), 2020; The Sicilian (Paola), 2021 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)

Age of Innocence (Nicole), 2020; The Sicilian (Paola), 2021 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)

Would you tell us a few words about your initiation into the world of art?

I grew up in a family that was half artists and half business people. Even as a child, it was clear to me that the life of the artist was not an easy one. After a liberal arts degree from Harvard College in 1985, I went to Wall Street. Then in 1996, the Muse beckoned and I started taking art classes in the evenings and on weekends; I discovered the New York Studio School, which has been my primary educational home for the last 20 years, with detours to the Art Students League in New York and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, where some important Greek artists studied: Apartis, Chryssa, Laskaridou, Sidiropoulos.

I had been flirting with making the switch to full-time working artist for many years, but didn’t have the courage. Then in 2017, I experienced multiple deaths of friends and family within a two-week period, forcing me to evaluate what I wanted to do with my remaining years on this planet, and I committed fully to making art! In September 2018, a well-known Greek collector acquired a work of mine, and I thought, “OK, now I am a professional artist”, followed shortly by the thought, “I had better get into the studio daily and make more, and better, work!”

Photo from the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York (© Guillaume Ziccarelli)

Photo from the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York (© Guillaume Ziccarelli)

Would you tell us a few things about your recent show at the Consulate of Greece in New York?

I am grateful to Consul General Konstantin Koutras, who invited me and the estate of Nassos Daphnis to exhibit at the Consulate from December 2021 to February 2022. To show at a prestigious venue in New York, the city to which both Daphnis and I came at a young age and chose to live and work, was an honor. Dr. Koutras, Cultural Attaché Evelyn Kanellea and their colleagues supported the exhibition strongly, and we had many visitors, ranging from Greek and Greek-American VIPs to members of the New York art world, including critics and curators from major museums.

Daphnis was an important artist, and his works can be found in the collections of many prominent museums like The Met, MoMA, Guggenheim, and Whitney in New York and the B&E Goulandris in Athens. Born in Krokees, near Sparta, in 1914, he came to New York around the age of 17. Like me, he had another career which supported him and his growing family, and like me, he did not have a conventional art education. I found the pairing fascinating because the two artists came from similar backgrounds to the same city, but made art that was at polar opposites, figurative sculpture and abstract painting. It’s a pairing worth ruminating on, including what does it mean to be a Greek-American artist?

Paul Laster, Curator, commented: “Taking a traditional approach to figurative sculpture, Petrides mines the past to create something new and when making his Pixel Fields/Aegean Series paintings, Daphnis tapped into new technology to update modernist abstraction. Petrides’ sculpted figures are perceptively born from the primordial mud of ancient cultures and modified in the artist’s hands, whereas Daphnis cleverly combined computer-generated graphics from an Atari ST with his own particular painting process”.

The artist in his studio (Life During Wartime from Hellenic Heads); photo ©Simatos/Cadena

The artist in his studio (Life During Wartime from Hellenic Heads); photo ©Simatos/Cadena

What is your working process?

My process is of my own invention, combining the ancient with the cutting-edge. Importantly, some of it is done in New York and some in the broad Athens area, including Piraeus and Boeotia.

I often start modeling by hand in natural clay in New York, looking at a live model or historical photographs. Next, the clay piece, still wet, is scanned in 3-D, becoming a digital file of millions of data points. This data is then manipulated in digital sculpting software, making alterations and enlarging it to up to three times lifesize. Then it might be sent electronically to Greece where it is 3D printed in plastic or CNC-milled in foam. I am happy to say that both these technologies are available in Greece. I work with one facility in Moschato and another in Ritsona, near Ancient Thebes.

When I have the enlarged sculpture back in the studio in Athens or in New York, I start on the piece anew, cutting with power tools, adding volume using materials commonly found on construction sites. Often the final form is cast in bronze, using the same lost-wax process that was used by the ancient Greeks 2,500 years ago. All of my castings to date have been done in Greece. Various patinas are applied to the final form in an expressionistic manner. From beginning to end, a piece can take a year and a half to make, from the first handful of clay to the piece ready for its exhibition.

Blue Girl, 2021; Kevin Belvedere, 2022 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)

Blue Girl, 2021; Kevin Belvedere, 2022 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)

You mention “Sculptural Precedents” in your working process. Explain.

I often draw inspiration from historic pieces, ranging from the Kouroi to Rodin, not to make a copy, but to see how an accomplished sculptor dealt with similar issues. Sometimes this helps me find my “way in” with my sculpture, although the end result may bear little similarity. For example, when I was starting on my piece related to the Destruction of Smyrna, The Catastrophe, I was thinking about my grandmother and how she might have looked and felt in September 1922 when the city was burned and she lost her whole way of life. Call it serendipity; on my drive back from Monaco, where I had a solo exhibition, to Athens, I stopped in Florence for a few nights. There, at the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo, I saw two works that left me in awe: Donatello’s Habbakuk (1423-26) and Michelangelo’s Deposition (1547-1555). When you look at The Catastrophe, you may pick up on subtle references to both masterpieces.

You have talked about your commitment to ancient Greek sculpture and to non-Greek sculptors, but what about modern Greek sculptors?

The two that excite me most are Yannoulis Chalepas and Yannis Pappas. Both are well represented at the National Glyptotheque in Goudi, which has to be one of the least visited museums in all of Europe. Whenever I visit I am usually the only person there. The Chalepas holdings by the Glyptotheque and by the Onassis Foundation are simply astounding. The other day when I was stuck on a part of Heroines of 1821, I picked up a Chalepas catalog (from the excellent Tellogleio exhibition) to see how he had dealt with a similar issue. It worked!

Yannis Pappas’ home and studio, an annex of the Benaki Museum in the Zografou area, are incredible, with a large cache of Pappas works and an air as if the sculptor were just around the corner and about to return and pick up his tools. Inspiring!

Frances Reclining, 2019 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)

Frances Reclining, 2019 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)

After all those years living outside of Greece–not just as an artist–would you say that your “Greekness” still defines your artistic expression in the same way it did in the beginning?

Yes, I believe so. Although I have lived most of my life in the New York area, my contact with Greece –the language, the culture, the country–has been continuous. Growing up in New York, my parents behaved as if they were on their way back to Greece, and indeed, upon my father’s retirement, that is what they did. As for me, I spent five of my teenage years in Athens, and like many Greek-Americans, visited every summer. So, I have always felt connected to my “Greekness”, generally as well as artistically.

What are your plans for the Hellenic Heads?

I am planning on showing the sculptures, including their supporting material (a 20-minute video, large posters giving more information on each historical period, a catalog), in venues around the world as an example of cultural diplomacy. After the premiere at the Embassy, the Hellenic Heads will travel to The Muses in Southampton, NY, exhibiting from June 16 to September 5, 2022.

Hellenic Heads: Heroines of 1821, Thalia; photo ©Simatos/Cadena

Hellenic Heads: Heroines of 1821, Thalia; photo ©Simatos/Cadena

You mentioned “cultural diplomacy”. What did you mean by that?

This is something I learned about from Ms. Eleftheria Gkoufa (The Benaki Museum), with whom I have worked in recent years. She acted as Cultural Manager for both the exhibition at the Consulate in New York and the one at the Embassy in Washington. She said “A traveling exhibition like this creates opportunities for intercultural dialogue. Although a personal exploration, Hellenic Heads is meant to convey some of the history of Greece as well as something of contemporary Greek identity. It seems these pieces have something to say to viewers, whether they are Greeks reflecting on how the Destruction of Smyrna affected their families or non-Greeks who only know the country as a vacation spot.

Some of the pieces are relevant outside of a nominally Greek context. For example, the Destruction of Smyrna in 1922 affected tens of thousands of Armenians. The 1940s saw the destruction of the Sephardic Jewish community, whose ancestors lived in Greece for millennia; The Acts state that when Apostle Paul visited Thessaloniki around 49 AD, there was already a synagogue established there.”

What else do you have planned for 2022?

In 2021, I visited Dubai for the first time and presented my work there in a solo exhibition. I fell in love with the people, both friendly Emirati and expat professionals. So, I will have a second solo exhibition there in November 2022, when I will present pieces that were created exclusively for the Emirates.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi (Intro image: George Petrides with some of his Hellenic Heads; photo ©Simatos/Cadena)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: George Rorris: “A painting is the sincere revelation of one’s soul“; Yannis Pappas, the sculptor of Greece’s historical figures; A Tribute to Greek sculptor Yannoulis Chalepas on the occasion of World Mental Health Day; Kostis Georgiou: “Art’s purpose is to provide a zone of unlimited paths”; Painter Dimitris Tzamouranis: “Art’s ultimate objective is the pursuit of beauty”

Ajitto, 2021; La Grande Chaumiere, 2019 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)

Ajitto, 2021; La Grande Chaumiere, 2019 (From the show at the Consulate of Greece in New York; photo © Guillaume Ziccarelli)