Dimitris Gkioulos (1984) studied math, translation and European civilization. He currently works as a translator and copywriter. Urban Misfortunes (Thines, 2020) is his fifth book and his first personal poetry book. His poems have been published in literary magazines in Greece and abroad.

Your latest writing venture Urban Misfortunes was recently published by Thines. Tell us a few things about the book.

Well, I started by writing short stories. Urban Misfortunes is my first personal attempt in poetry. Before that there was Antartiko2 which was an almost DIY poetryproject along with Konstantinos Papaprilis-Panatsas, which went surprisingly well. Still does actually. I was happy that Thines owner and editor, Zizi Salimpa loved the draft of Urban Misfortunes and this book has been a pleasant ride so far. I mean, I love having my messenger inbox filled with hundreds of photos of drying racks (a trademark object for the misery inhabitants of urban centers face), inspired by the cover of the collection, designed by Melissanthi Salimpa.

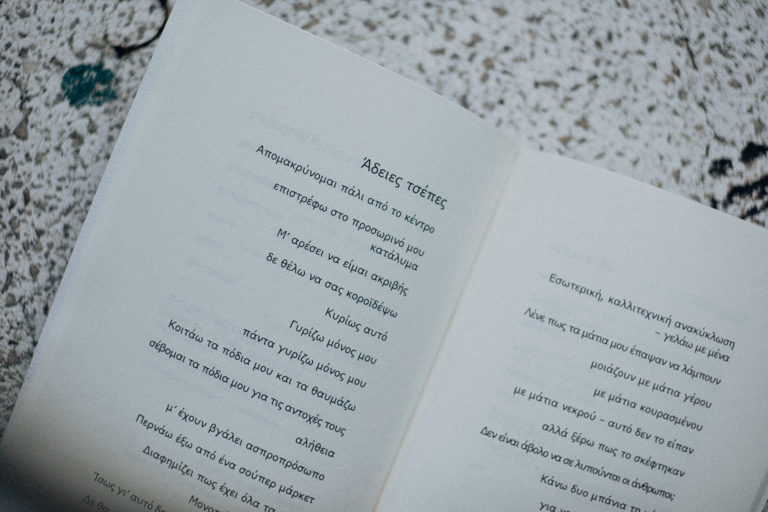

Urban Misfortunes was first of all, a way to understand how the world vastly changes and where we find ourselves in that process. In every crisis in history, there is a generation, one at least, suffering great consequences. This is what Urban Misfortunes is, a way to talk about what we are living. To find out, the collection is visiting the past through three family lunches, a quite common tradition in Greek families, on three different Sundays throughout the years. At the same time, there is the effort of surviving in an urban environment in the middle of a wild gentrification; last but not least, the collection tries to deal with loss, specifically the loss of my mother. Way too many subjects one might say, but still, complexity is a core element of our times.

The notions of time and place are central to Urban Misfortunes. How does your poetry converse with the burden of history, the precarity of the present and the unforseeability of the future?

Indeed. Both time and place are key elements of the collection. We come from somewhere and we are heading towards somewhere, but we are not alone. We carry our ancestors, the little stories of the land we inhabit and the relations we try to form, simultaneously. We cannot ignore the past, there lie most of the explanations of the things we live, there we can find out more about the way we react towards the challenges of life, there may be the key to turn the tables, so that the precarious present will turn into a better future. A future that, yes, at the time being is unforeseeable. So, here in Urban Misfortunes, my poetry acts like a vehicle. Going back and forth in time, in places, living in the present, trying to talk about a future that can be something else, not dark. It is the least and at the same time the most, poetry can do.

Your poetry seems to reflect the frustrations and losses, the hopes and expectations of the so-called ‘generation of the crisis’. Which are the main themes your writings touch upon? Where does the personal meet the collective in your poems?

‘Generation of the crisis’. Yes. I ‘ve been told so. And it something of an honor. I mean, being told that I am somehow capturing what a whole generation is living? Yeah, I am honored. Actually, it is something that was a key element of the Antartiko2 project. There, alongside with Konstantinos, we tried to put into words this feeling of frustration of our expectations. Growing up, our generation was promised a better life than the one our parents lived. I am not saying that my generation agreed on some kind of contract (apart from the social one) and they tricked us, but still, up until now, we are the most equipped, the most trained and well-educated generation and we saw (we still see) our hopes and aspirations crashed and burned.

In Urban Misfortunes, I am trying a totally different approach. The poems are not delivered as slogans on the wall. Here I am not using the same conveniences I’ ve used previously. The political statement is subtle. It is present and it is intense, but yes, subtle is an accurate way to put it, I think. Ηow could it not be political, our lives suffer as a result of certain policies implemented, our relationships of all kinds, our prospects that vanish, our friends that leave to work abroad. Everything is political.

I am certain that Urban Misfortunes is able to converse both with an American worker in Amazon warehouses who participated in the founding of his union just a few days ago, and with a Chinese researcher who lives in a tiny apartment in a Chinese metropolis and does not know what to make of her life. And with all the people in between. At the same time, I want my poetry to be able to converse with the outcasts of the so called first world, the refugees from all over the globe, those who fight for equality etc, but I do not want to do that by writing like I am one of them. Even in this reality, I am well aware of my privilege, of being a western, white male. But rest assured that I will be fighting alongside them until they have their voice. And, although I am often asking myself how can it not all be political, I can see that many people doing (yes, doing) art, do not want to raise questions or even converse with the here and the now, they just want to be easy to digest, likable. I am not interested in that.

“Poetry, can and does record the time; if it is good, it can show you a perspective that you have not even imagined, but at the same time the poet participates in life, experiences its frustrations, lives in the here and now. The poet may speak of a potential future, but he also fights for the here, for the now”. How does your poetry converse with the world it inhabits? Could poetry be used to talk about radically different realities?

I believe that good poetry can come from something you may experience, live or outlive and you take this something and transform it into something else that can speak to people. If it also stands the test of time, then, it is great poetry. I am trying to be a good poet. I am not just writing down staff as a journal I display in public. At the same time, I am not unambiguously defined. I am not sitting in a room, far from everything, writing. I have to go out and survive every day. I am aware that intentionally or unintentionally, art contributes to the formation of a collective unconscious. It is our most sensitive, collective antenna. Art is there to show us all the possibilities as long as things remain claimable. To inspire -even when everything else has failed, that one person which may determine our fate, as Karl Marx would put it. But the artist is a person who participates in society, its struggles; he/she enjoys first hand these small wins, he/she has to live with the great losses.

Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their work published? What role do the social media play in the promotion of new literary voices?

Well, I do not know where to start exactly. There is so much to be said on that subject. I strongly believe that literature, art in general, has not been one of the priorities of the Greek state for quite some time. With the pretext of the Greek crisis, funding was reduced gradually but drastically. If we add to the equation the inadequate way art is being taught in public schools, you feel that it is not considered among the top priorities. Otherwise, how can someone explain that contemporary literature and poetry are not being taught in schools? A naive question: why don’t writers and poets of today serve as examples for students interested in literature and poetry? Couldn’t such interaction serve as inspiration or even as a deterrent to follow that path?

Also, there should be more concerted state support in promoting Greek literature and poetry abroad. Other Balkan states for example, have funds for promoting their writers. These include funds for translating their work in other languages. This is used as a means of promoting their local culture in a globalizing world. Here, this is mostly implemented with funds coming from the European Union, while there seems to be a lack of long-term planning as far as culture is concerned. I believe there is very good quality of works both in poetry and in literature in this land that unfortunately stays inside the Greek borders.

This affects both publishers and writers, both published and aspiring ones and I’ll explain what I mean. Since most publishing houses struggle to survive and the majority of Greek poetry for example is not a profitable choice in editions, it sometimes happens that publishers pass on the cost of publication to the poets and writers themselves, creating a balance where someone who has the funds can be published whether the published content is good or not, and someone who does not have the funds gets rejected even if the content produced is worthy of being published. Luckily, not all publishers are like that, but they look more and more like Don Quixote, romantics chasing the windmills of great art in a world that is becoming more and more cynical. This is another sector where the state could intervene and help towards the publication of better content. It is understandable that we live in a capitalist society with specific rules, but art and its works, even in this context, cannot be treated as sterile goods, they are and they will be much more than that.

The social media is another “place” where people of the same taste and interests can “meet”. During the pandemic especially, there was no alternative, so yes, social media can be helpful and let you find new voices. I am talking more as a reader, who always wants to find something challenging to read, but yes, as a writer also, social media are a means of promoting but also getting in touch with readers who want to talk you about your work, something that, to this degree, has never happened before in history. As everything, social media have pros and cons, it is up to anyone to find the right balance.

For the majority of Greek writers, writing is not a main profession but rather a leisure time activity. In other words, earning a living through writing is the exception rather than the rule. Could things be otherwise?

That is actually a key question. Not only is writing a complete professional activity but for a small minority, but also the writers themselves treat writing as a sideline activityor hobby. We (people of my age) tried, during the first quarantine, to form something that we imagined that at the end of the road would lead to the establishment of some sort of union that would fight for the rights of authors. Τhis was triggered by the fact that artists were among the most adversely affected especially during the first months of the pandemic. The response from those we reached for that purpose was little to zero. At the same time, the existing associations function more as think tanks and less as means of claiming rights.

I feel that we are moving in a direction in which art should be a profitable activity for the state, otherwise it will be left in the hands of the various cultural institutions, which, however, have their own agendas. That’s exactly why we need to demand more government care, now more than ever.

Can things be otherwise? Yes. Is it something I see occurring in the foreseeable future? No. Does this mean that we should stop doing what we think is right? No. Maybe, next time we meet and talk, things will look a little brighter.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE