The composition of the Greek soil, coupled with the relatively high sunshine duration, has contributed to the development of ceramic art in the country since the antiquity. To this day, the art of pottery has maintained its importance in many parts of Greece; alongside efforts to record and preserve its traditional cultural heritage, the country sees a new generation of ceramists who explore the possibilities offered by the material’s versatility.

Antiquity

The word “ceramic” itself originate from the ancient Greek word keramos, meaning “potter’s clay”. Containers and other objects made of clay are among the most common exhibits in Greek archaeological museums, since they are the most common objects found in archaeological excavations. Approximately 80,000 intact decorated vases have been discovered in the region of Attica alone.

In Greece, both in ancient times and today, there are many areas where clay, or loam, is found. In ancient times, clay was a convenient and affordable material, unlike copper and precious metals. It was therefore preferred for making everyday utensils, such as vessels for storing and transporting oil, wine and water, as well as cookware and tableware. Despite serving a functional purpose, clay vessels were often elaborately decorated, especially those intended for special occasions.

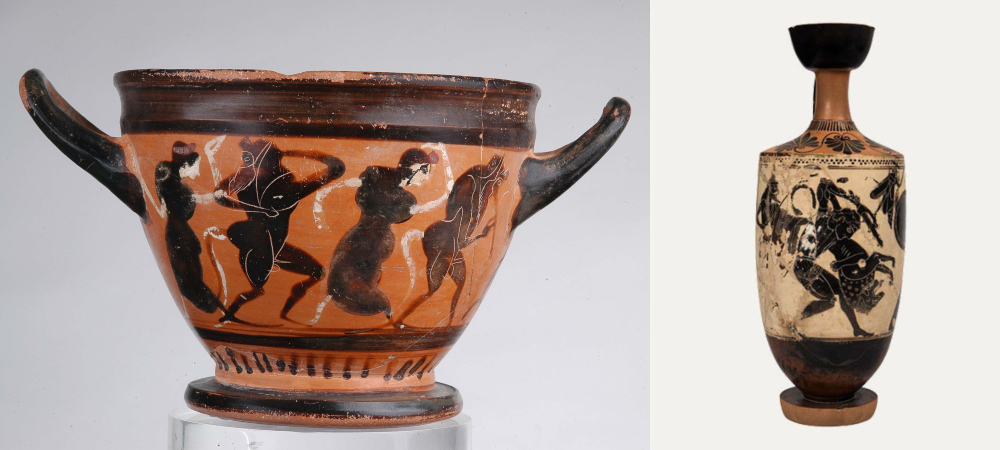

Left: Black-figure skyphos, Archaic 525 – 500 BC (Museum of Cycladic art); right: Black-figure white-ground lekythos, Late Archaic 500 – 490 BC (Museum of Cycladic art)

Left: Black-figure skyphos, Archaic 525 – 500 BC (Museum of Cycladic art); right: Black-figure white-ground lekythos, Late Archaic 500 – 490 BC (Museum of Cycladic art)

Athens, and Attica in general, was especially known for its production of fine pottery, due in part to the rich supply provided by the fluvial clays deposited by the river Eridanos. The word keramos is the origin of the name of Kerameikos, an ancient demos where the potters’ workshops used to be, and which is now an important archaeological site; other cities and regions known for their production of luxury pottery included Corinth, Laconia, Euboea and Boeotia.

The vases provide an important testimony to the everyday life customs and religion of ancient Greeks. The adventures of gods and mythical heroes were among the most popular subjects for vase painters. The daily occupations of men and women are also described in great detail. From the 5th century BC onwards, white vases with painted and polychrome details give us a glimpse into the art of painting in classical Greece, specimens of which have not been otherwise preserved.

The potter, the craftsman who made the vase, and the pottery painter who painted it were usually two different people, as indicated by the signatures on the vases, where the word epoiesen (“made, created”) denotes the potter and the word egrapsen (“drew, painted”) the painter. Sophilos, Euthymides, Euphronius, Amasis, Nicosthenes are some of the names of potters and pottery painters that have been preserved this way.

Left: Black-figure lekythos, Classical 475 BC (Museum of Cycladic art); right: Red-figure pelike, Classical 450 – 440 BC (Museum of Cycladic art)

Left: Black-figure lekythos, Classical 475 BC (Museum of Cycladic art); right: Red-figure pelike, Classical 450 – 440 BC (Museum of Cycladic art)

The evolution of ancient art is generally divided into four periods, namely the Geometric period (1050-750 BC), the Archaic period (750-480 BC), the Classical period (480-330 BC) and the Hellenistic period (330-50 BC). However, as far as ceramics are concerned, the distinction between the periods is based on the type of decoration and the technique used; pots of the Protogeometric style, which emerged around the mid 11th century BC, featured simple geometric motifs in black paint, while the Geometric style included more intricate motifs; the Orientalising period, which began in the later part of the 8th century BC, was marked by a heavy influence from the Eastern Mediterranean and the Ancient Near East.

The end of the 7th century BC saw the emergence of black-figure pottery, a style which was especially common until the 5th century BC; this was succeed the red-figure style, which became the dominant one until the late 3rd century BC, although black-figure ceramics were still produced as late as the 2nd century BC.

The Hellenistic period was marked by the emergence of several different techniques, from elaborately painted and vibrantly colored vessels to much simpler ones, reminiscent of the older geometric styles; mould-made relief pottery was also representative of this era. Important ceramic centres were established in various parts of the Hellenistic world, notably in Pergamon, Pella and Athens.

Left: Red-figure “fish-plate”, Late Classical 350 – 340 BC (Museum of Cycladic art); right: Tanagra figurine, Hellenistic 100 – 1 BC (Museum of Cycladic art)

Left: Red-figure “fish-plate”, Late Classical 350 – 340 BC (Museum of Cycladic art); right: Tanagra figurine, Hellenistic 100 – 1 BC (Museum of Cycladic art)

Apart from pots and vases, it is also worth mentioning the long history of Greek terracotta figurines, widely used as religious or funerary offerings, which later also acquired a decorative function, but also often used for dolls and other children’s toys. The most famous specimens are the renowned Tanagra figurines –of which many have been excavated in the eponymous town of Boeotia– produced from the later 4th century BC and known for their elegance and great detail.

Ceramics in modern times

Ceramics have continued to evolve over the centuries. In many parts of Greece, there are still pottery workshops that produce objects of high aesthetic value. Especially for many islands pottery remains an important aspect of their identity. The ceramics of each region are distinguished by their colours, decorative patterns and also the words used to describe them. Thus, depending on the region, the container for transporting and storing liquids is referred to as stamna, víka (Messinia), bótis (Patras, Corfu), balathouni (Karditsa), vytína (Dodecanese), koumari (Lesbos) or laïna (Crete).

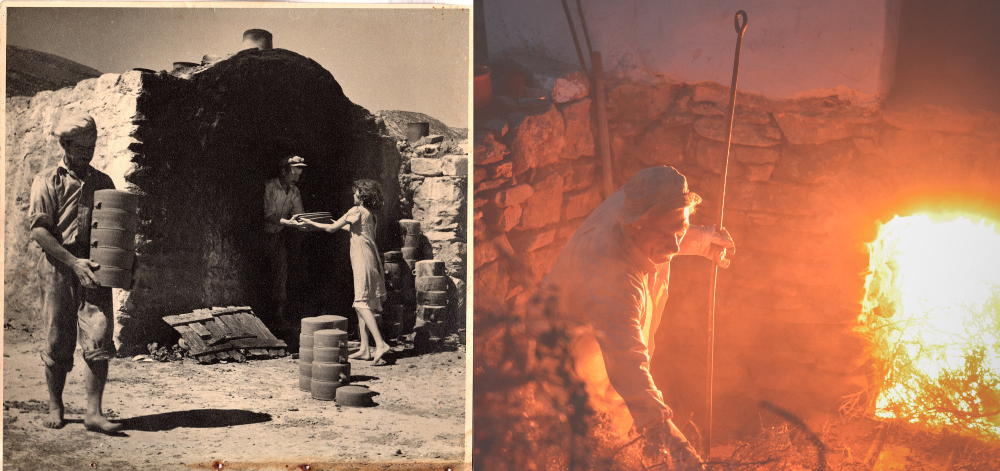

Left: pottery being taken out of a traditional kiln in Sifnos; right: lighting a kiln (photos ©Sifnos Pottery Association)

Left: pottery being taken out of a traditional kiln in Sifnos; right: lighting a kiln (photos ©Sifnos Pottery Association)

Sifnos is one island particularly famous for its production of pottery, which has its roots in ancient traditions, and is an indispensable part of its economy. The island’s soil and long periods of sunshine have played an important role. The earliest specimens discovered there are dated to the Early Cycladic period; to this day, there are more than 15 workshops in operation producing ceramics both for domestic use and for decorative purposes.

This tradition’s importance had been partially overlooked in the recent past. Today, however, there is a growing interest in traditional ceramics, which has led to efforts to document and preserve local techniques. In this context, the Greek Ministry of Culture has included the ceramic tradition of Sifnos as well as the ceramic tradition of the Kourtzi family from the island of Lesbos in the national inventory of intangible cultural heritage of Greece.

Another representative example of a rekindled interest in the significance of pottery as part of Greece’s cultural heritage is the Centre for the Study of Modern Pottery– G. Psaropoulos Foundation. The centre conducts fieldwork in many regions of the country. As part of its activities, it has identified traditional workshops and kilns, recorded the production process and filmed traditional potters in action. The results of its research are published in books and scientific articles. The centre also organises educational programmes and ceramic workshops for adults and children.

Recreation of a traditional potter’s workshop at the Centre for the Study of Modern Pottery– G. Psaropoulos Foundation

Recreation of a traditional potter’s workshop at the Centre for the Study of Modern Pottery– G. Psaropoulos Foundation

On the other hand, contemporary ceramists claim the right to present pottery as an art form in its own right, with deep historical and contemporary origins and countless possibilities of expression. They are therefore ‘rediscovering’ clay as a material to use in conceptual works of art.

Outstanding contemporary Greek ceramicists

One of Greece’s most prominent ceramic artists, Eleni Vernadaki, has radically revived the art of cemarics in her over 50-year-long career. In her early works, eclectic references to local ceramic tradition and ancient Greek vases emerged. In the course of her career, though, the dominant feature in her works was to be the dynamic development of the principles of 20th-century ceramic “modernism”, while she would also produce works that were a distinct expression of the field described as “conceptual ceramics”. Vernadaki would finally manage to overcome the distinction, firstly, between “high” and “minor” art and, secondly, between the utilitarian and non-utilitarian object, by approaching ceramics as a “component expression of the visual arts” as she herself described it.

Works by Eleni Vernadaki from her “Olympiaka” series, 2003-2004; left: earthenware with white glaze, painted with black ceramic stain, with added decoration; right: Earthenware with white glaze, painted with black ceramic stain, with added decoration (photos from E. Vernadaki Archive)

Works by Eleni Vernadaki from her “Olympiaka” series, 2003-2004; left: earthenware with white glaze, painted with black ceramic stain, with added decoration; right: Earthenware with white glaze, painted with black ceramic stain, with added decoration (photos from E. Vernadaki Archive)

Another representative Greek ceramist was Panos Valsamakis (1900-1986); born in Aïvali (Asia Minor), he attended the Athens School of Fine Arts and specialised in ceramics at the Saint-Jean-du-Désert School in Marseille. His work unites in a unique way oriental, Greek and European influences. His studio in Maroussi is still in operation.

Panos Valsamakis, Inner Vision, Ceramic panel (colour glaze), 1975 (from the National Galllery-Alexandros Soutsos Museum)

Panos Valsamakis, Inner Vision, Ceramic panel (colour glaze), 1975 (from the National Galllery-Alexandros Soutsos Museum)

Mary Hatzinikoli-Sarafianos (1928-2020), speaking of her attraction to ceramics, says: “I studied ceramics not as an applied art, as it was then perceived here, but as an essential means of creative expression, with enormous potential. It was precisely these possibilities that satisfied my innate need to create material and texture, the two elements necessary for the consolidation of a form and the formation of a concept. As soon as I realised this, I lived making ceramics”. Hatzinikoli has created paintings on ceramic tiles to be integrated into buildings as well as sculptures of various sizes. She has experimented with the material by creating her own clay with great plasticity and transparency. She was also the first artist to use moulds to create small, reproducible and relatively inexpensive works of art, making it possible for the general public to acquire a work of art.

Left: Head, right: Human back; works by Mary Hatzinikoli-Sarafianos

Left: Head, right: Human back; works by Mary Hatzinikoli-Sarafianos

In the same spirit of ceramic renaissance and conceptual research, the number of exhibitions and spaces that showcase the new generation of ceramists is also increasing. The French ceramist Eleonore Trenado-Finetis has created the Mon Coin Studio gallery in the centre of Athens, dedicated to contemporary Greek ceramics.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Eleni Vernadaki: Modern Greece’s Priestess of Ceramic Art ; Kerameikos, the necropolis of Athens; A brief history of Greek jewellery; A World of Fashion – Made in Greece

N.M. (Based on the original article which appeared on Grèce Hebdo; Intro photo: the showroom of a contemporary pottery workshop in Sifons, photo ©Sofia Katzilieri)