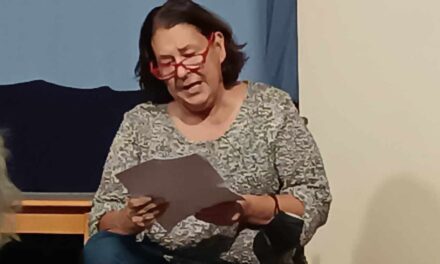

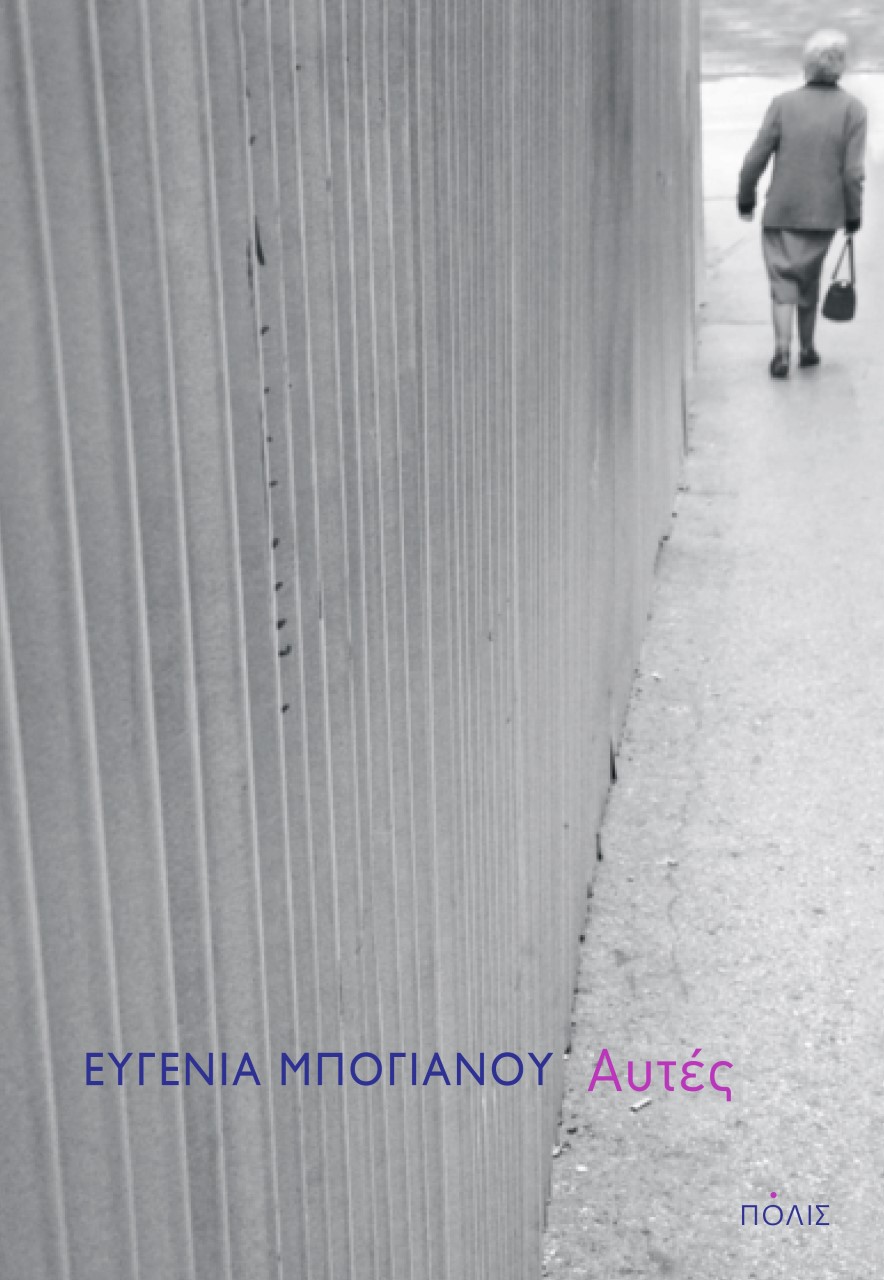

Eugenia Bogianou was born in Thessaloniki and lives in Athens. She has written four short story collections and two novels. Her last short story collection, entitled These Women, was published in May 2022 by Polis editions. She writes book reviews for the newspaper Avgi.

Your latest writing venture titled [These Women] was recently published by Polis Εditions. Tell us a few things about the book. Could you elaborate on the title?

The book comprises 24 short stories, as many as the letters of the alphabet, with women at various ages and in different situations as their protagonists. Starting from childhood, adolescence, youth, adulthood and old age, I wanted to talk about all those things that oblige women to be restricted within the boundaries of their gender. Of course, the list could be much longer. My heroines are women whom I do not name, but address only by their initials, precisely to emphasize this condition of anonymity. The fact that it could refer to any woman, at any time.

I could say that the book is about an ageless woman with many faces, who changes by entering from story to the next.

The title These Women, in addition to being a demonstrative pronoun that we use when we want to show someone without naming them, also echoes all the disparagement that the female gender has received over time and continues to receive. After all, the patriarchal society that surrounds us, no matter how flexible and adaptable it is, remains the same at its core, with its main traits unchangeable. That is why it so often manifests its dark face with vulgarity and deadly violence.

But the title, when seen on the heroines’ part, echoes something of their insolence. They are women who, one way or another, react when the time comes. Women who experience a silent revolution inside them. They may be silent most of their lives, but there is a point, a limit, and when they cross it, they revolt through a minor or major act of resistance. Even when the price, at times, is high.

You have chosen to talk about the women’s situation in a period during which acts of violence against women have increased while regressive institutional decisions aim to hinder women’s right to self-determination. Within this framework, which are the main stories that These Women chose to narrate?

We unfortunately live in dark times. I began to write the book shortly after the first quarantine. It was then, under unprecedented conditions of confinement and isolation, that I wanted to talk about the violence we experience in our everyday life and which, unfortunately, is mainly aimed at women. I heard and read about an increase in domestic violence, and I began to imagine all this bleakness, the helplessness, the silent rage. A woman in confinement who falls victim of violence – physical, emotional, psychological – by a boyfriend, a husband, a father.

I was wondering how anyone can talk about this violence? Of everyday life. We hear all the time about femicides. That is, the ultimate form of violence that someone exerts on a woman, questioning her right to be a free person. Indeed, this is the worst form, but daily continuous violence, which leads to more and more violence,can take many forms and have many faces, aiming at assimilation and submission. I am talking about these many faces of daily violence in These Women.

“In These Women, I wanted to move away from absolute realism, opening up to paradox; sometimes I chose to personify concepts while at others to give a voice to inanimate objects”. What role does language play in your writings?

Language is everything. Therein lies all the difficulty. In the style and rhythm of narration. Quite often the story is there but there is no way to tell it. After all, we are not talking about brochures. We are talking about texts whose value has to do with what we call literature. That is, with a situation that is created through language.

Ι personally struggle a lot until I find the tone of the story. Quite often one word seems to undo the value of the previous. But there is a point at which I know I found what I had been looking for. From then on, I move forward, definitely not unhindered, but with much more confidence.

It has often been argued that in the Greek history of literature, the notion of the political is male dominated, although alleged as universal. Do you think that literature still has open accounts with women? In other words, is there a place for women in the Greek literature of the 21st century?

Women writers, both in Greece and abroad, have started to dig really deep. We encounter sharp and subversive approaches. Issues such as gender identity, gender roles, inequality, feminism, patriarchy, social automatisms are increasingly coming to the fore as a result of accumulated knowledge, experience and chronic dissatisfaction. These are issues that male writers have also dealt with but I reckon no one can speak more incisively about racial discrimination, for instance, than a black writer. Because racism has been felt on his/her skin.

Many women writers, for example, have spoken very boldly about the limits and hardships of motherhood. Of motherhood as a social construct, which sets boundaries and assigns roles. Of motherhood as a barrier and not as a ‘great miracle’. There are no more sacred, untouchable issues. Everything is debatable. Everything is fluid and everchanging. Women writers – as every writer should, of course – don’t mince their words, don’t come easy on anyone. Tοput it lightly, I would say they have set themselves loose.

Do you agree with those who argue that Greek writers have preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives?

Indeed, Greek writers serve the short form with stubbornness and passion. Every year several important collections of short stories stand out, which is not so often the case with novels. There is a long tradition in the short story. In the 19th century, but also at the beginning of the 20th, many great figures excelled in short form. That is, in this precise process where you aim at a single moment and try to illuminate it from all aspects, leaving a strong and distinct mark. In other words, you try to capture a version of reality with intensity and speed; something that might suit Greek writers more in terms of idiosyncrasy.

Yet, it is perhaps too risky to talk about idiosyncrasies. After all, pitfalls lie in generalizations. Nonetheless, short stories definitely surpass novels.

What role are writers called to play in times of crisis? How has both the recent socio-economic crisis as well as the current pandemic affected you both as a writer and as a reader?

It is impossible for writers not to be influenced by the social conditions, the political situation and the surrounding atmosphere of their time. They move within this world and not outside of it. Observing what happens around them is one of their main weapons and literature is a unique mirror of everyday life. Of course, literature is not called upon to change the world – how could it? -, but to comment on it by recreating it. The world and its evolution change literature, and not vice versa. Literature suggests interpretations. It paves the way for the solution but it doesn’t provide the solution itself, if there is indeed one. Yet, if it doesn’t keep up with its time, it becomes meaningless.

Needless to say, my own writing derives both from my personal and social consciousness. And it is deeply influenced by what surrounds us.

“When it comes to literary criticism, the euphoric freedom of writing gives way to a more detached approach that rests on rules, not inviolable but definitely rules”. Would you say that writing and literary criticism constitute communicating vessels?

Since I happen to be involved in both, I would say that the one definitely feeds the other, given that reading is at the core of both.

But, generally speaking, they are two different, autonomous fields, with different characteristics, special requirements, and a distinct approach.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Foteini Christofilopoulou