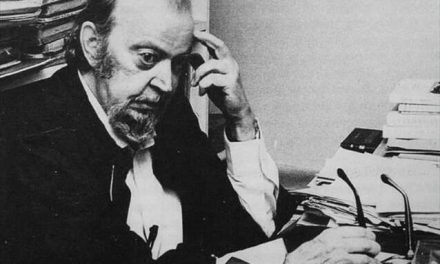

Lila Konomara was born in Athens. She studied contemporary literature in Paris and worked as a professor at the French Institute of Athens. Her first book was Μακάο – Δύο νουβέλες [Macao – Two novellas] (Polis 2002, Metaixmio 2005, Kedros 2018), which garnered her the First Book Award by Diavazo magazine and was nominated for the Greek National Book Award in the Short Story category.

She has published the following novels: Τέσσερις εποχές – Λεπτομέρεια [Four seasons – A detail] (Metaixmio, 2004), Στις 11 και 11 ακριβώς [At 11 and 11 sharp] (children’s novel, Papadopoulos, 2005), Η αναπαράσταση [The representation] (Metaixmio, 2009), Το δείπνο [The dinner] (Kedros, 2012), Ο χάρτης του κόσμου στο μυαλό σου [The map of the world in your mind] (Kedros, 2018), as well as a collection of short stories, Οι ανησυχίες του γεωμέτρη [The geometer’s concerns] (Kedros, 2014). She is a member of the Hellenic Authors’ Society and a founding member of the online literary review O Αnagnostis. She is a translator of French literature and a contributing editor in various newspapers and literary magazines.

She has served as a judge for the Greek National Book Awards (2015-2016) and for the Greek National Literary Translation Awards (2017-2019). In 2017 she was awarded a fellowship by the Bavarian Ministry of Culture (Villa Concordia – Bamberg).

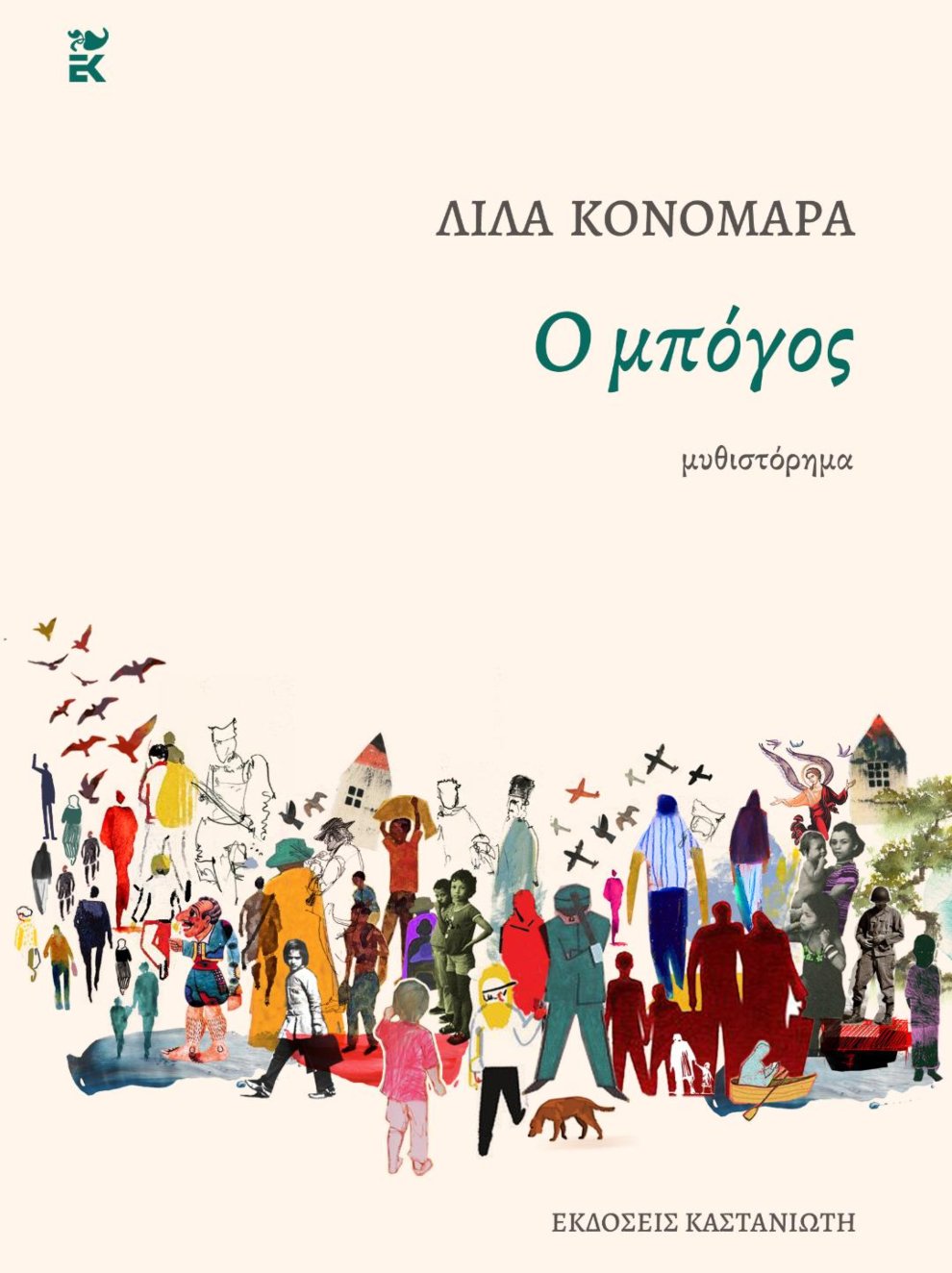

Your latest writing venture O μπόγος [The Bundle], which was recently published by Kastaniotis, was favorably reviewed upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book. What does the title allude to?

The book opens in 1911, in the Greek part of Macedonia. A shepherd stumbles upon an unconscious man in the outskirts of a remote town. The man carries no identifying information and when he comes to his senses he claims to have no prior memories. The town’s inhabitants name him Manolis. He settles there and gets to know the townspeople: Andreas Kechagias, an industrialist and landowner, and Marina, his wife; Lambros, a priest; Fotiadis, the town doctor; Antonis Metallinos, a contractor; Nondas, the owner of a decrepit hotel; Lefteris, a kiosk owner and police informer; Anthoula, the “witch,” a herb healer, and many others besides. A few weeks later and the body of a raped and murdered young girl is washed up in the river.

Manolis, the central figure of the narrative and its binding thread, will play a crucial role in the lives of the inhabitants and the history of the town. On one level, Manolis is the quintessential Greek, with all his faults and strengths, his grandeur and shortcomings. One could also claim that Manolis is the perpetual “Other,” a part of whom constantly eludes us and whom the townsfolk each interpret according to their own fears and desires: a saint or a devil, an artist, an object of desire, an enemy of the country, a benefactor, or a convenient scapegoat. Manolis paints the frescoes of the church, inserting scenes that depict the town, thereby acquiring the identity of the creator, the man who tries to transcend his mortal existence and, like Prometheus, become God.

The titular “bundle” is what we all carry inside: our life experiences, our dreams, and frustrations. However, it also represents the history of this land, the ceaseless movement of populations, the immigrants, the settlers, the nomads, and the transients, all of whom left their indelible mark on Greece over the course of the 20th century.

A whole century of Greek history seems to unfold while reading the book. Where is the meeting point between the personal and the social, the individual and the collective?

The plot unfolds over the course of the 20th century, following the country’s history (1911-2018) through the lens of its heroes’ individual stories. Their lives are inextricably linked with the great conflicts, upheavals, and rearrangements that transformed Greece at every level: be it geopolitical, economic, social, or cultural. In the course of the novel’s timeline, Greece acquires new territories, and the characters fight in three different wars—the Balkan Wars, World War I, and World War II—before participating in the debacle of the Greek Civil War (1944-49) and later that of the Regime of the Colonels (1967-74). They face crisis after economic crisis, the country’s utter bankruptcy, as well as periods of recovery and prosperity. What was once a rural society is gradually transformed into an urban one. The town’s inhabitants come into contact with Western culture through travel, through the novelties of radio and television, and in the process the West leaves its mark on the perceptions, way of life, and the course of modern Greek society.

I chose Macedonia as the stage for the events of the book, because historically it has served as a crossroads for many nationalities, languages, and religions. I also wanted to explore and capture the essence of the Greek psyche as it changes over time, its wealth and contradictions, its ideological and political transformations.

Your writing career spans 20 years. What brought you to writing and what continues to be your driving force?

I have always been writing, I have always known without knowing it that I would write, as is often the case for certain things we carry inside us. Every person, I believe, has their own place in this world, and when they find it, they arrive at a wonderful balance—inner and outer. It goes without saying that it’s not all fun and games—quite the opposite. The act of writing requires great reserves of endurance, faced as we are each morning with the blank page. Failure and defeat mark the way despite our hard work, while at the same time we have to deal with the requirements of everyday life, making a living. But there’s no other choice. Writing is a deep inner need which gives meaning to a life, along with the love of close friends and family.

“A recurrent theme in my books is multiple readings of people and events. This is the reason why the story is often narrated by more than one point of view, and the interpretations remain ambiguous.” Tell us a little more.

In The Bundle, as in my other books, the story is narrated by many of the novel’s characters, in order to highlight the polyphony that governs reality. The various events and heroes are illuminated from different angles in order to reveal different aspects, different interpretations, which in turn may be overturned later. Ιn the book, this diversity is increased further by granting a voice to the elements of nature: the trees, the birds, the snake, the river. Nature has its own story to tell, even though we insist on ignoring it and mistakenly assuming that we are the masters of the world. History is not limited to recorded dates and events, but includes also the oral testimonies which are passed from generation to generation, as well as the folk tradition which conveys its message through fairytales, folk songs and legends, the sense of an era.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

Language is not only the building block of my writing—it’s also one more of its protagonists. I grew up in a rural part of Greece—where people live closer to nature and the oral tradition—and I was always more attuned to the richness and the singular ability of the Greek language to create images in the mind. Sometimes when I write, what comes first is the actual “hearing” of my texts, as if a deep internal rhythm dictates the sentences I write. Each word in itself carries a whole story, and they have a potential which frequently exceeds the intentions of the author. The text reveals the unutterable, those psychic realities connected with the collective unconscious.

How does literature relate to the world it inhabits? Could it be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

Literature does not exist in a vacuum. Whether it faithfully represents reality, or transubstantiates it, or even turns its back to it, literature is the consequent of a specific socio-political circumstance. Of course, it is necessary to move beyond the concerns of the day, to challenge them rather than submissively follow them, in order to arrive at the substance of things and capture the sense of a whole era.

The works of modernism and postmodernism, as well as fantasy literature—be they fairy tales, science fiction, or the fiction of Borges or Kafka—have depicted utopian societies, dystopian regimes, and parallel realities. By opening a crack in the armor of realism, they have introduced ambiguity and doubt. They play gameswith time, the divisions between past, present, and future disappear, as in children’s language—the presence of an absence, what exists behind and beyond mere events, is revealed. But apart from existential issues, the allegorical use of the imaginary allows also the questioning of social and political institutions. Since, in one way or another, literature always engages in conversation with its own time.

How do Greek writers relate with the world literature? Where does the national/local meet the universal?

Contemporary Greek literature is in full flower, and is characterized by great diversity. In general, it follows the same trends as in the West, whose effect is particularly evident in the younger generation. Unlike the previous generation of writers, who mostly dealt with issues pertaining to Greece and the Greek identity, the new generation is marked by cosmopolitanism and extroversion. Social, historical, and crime fiction is flourishing, as well as autofiction. There is also a trend, like elsewhere, for fiction engaging with issues related to gender, ethnicity, or religion, that until recently were considered taboo. There is an equally strong trend for more reality in literature, for “biographies” and “real stories,” in an obvious effort to find some meaning in our increasingly fluid reality. What sets apart contemporary Greek literature from its counterparts is that poetry and short stories still command a significant part of the audience’s attention, and both have produced—and still do—excellent works of the highest quality.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: © Michael Aust