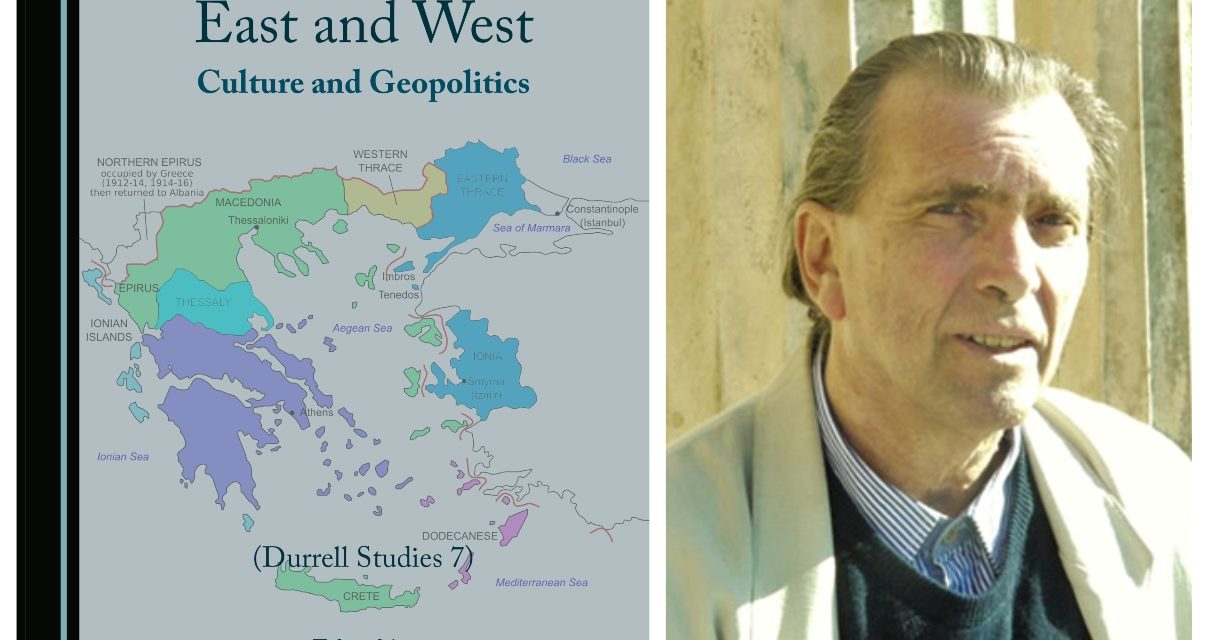

The new collection of essays “Greece Between East and West: Culture and Geopolitics” looks at the central geopolitical situation of Greece and its pivotal role in the Balkans and the Levant. The trend towards “modernisation” and “westernisation” is examined in the light of traditional values in culture, language, history and politics which reflect Greece’s eastern legacy and the continuing presence of that legacy in contemporary society.

“Greece Between East and West” features an interview with a film-maker Tassos Boulmetis, original writing by historians, political scientists and literary critics, grouped into three major themes: “Political Life – Past and Present”, “The Balkans and the Levant: Two Fictions and Three Cities” and “India, China and the Rediscovery of Greece”. Additionally, the book features a Foreword by Roderick Beaton, one of the most distinguished scholars and commentators on Greek history and social affairs, and current Chair of the British School at Athens.

Richard Pine, the editor of “Greece Between East and West” is Director of the Durrell Library of Corfu, were he lives, and series editor of “Durrell Studies”. He has contributed “Letters from Greece” to The Irish Times since 2009 and also wrote the column “The Eye of the Xenos” for Greek newspaper Kathimerini. His analysis and assessment of Greek social, cultural and political life is trenchant, up-front and passionate. He is the author of many books on literature and music, including: Lawrence Durrell: the Mindscape (1994/2023), The Eye of the Xenos: letters about Greece (2021) and The Disappointed Bridge: Ireland and the Post-Colonial World (2014). His collected essays on cultural politics from 1978 to 2018, titled “The Quality of Life”, was published in 2022.

Richard Pine spoke to Rethinking Greece* on the concepts explored in this new book, Greece’s legacy in the Levant, the unknown connections between Greece, China and India, the geopolitics of the Balkan region, and finally, on why he believes the ideological dilemma between “East and West” is still relevant today.

What was the concept behind the making of the book? How did you choose the writers and subjects?

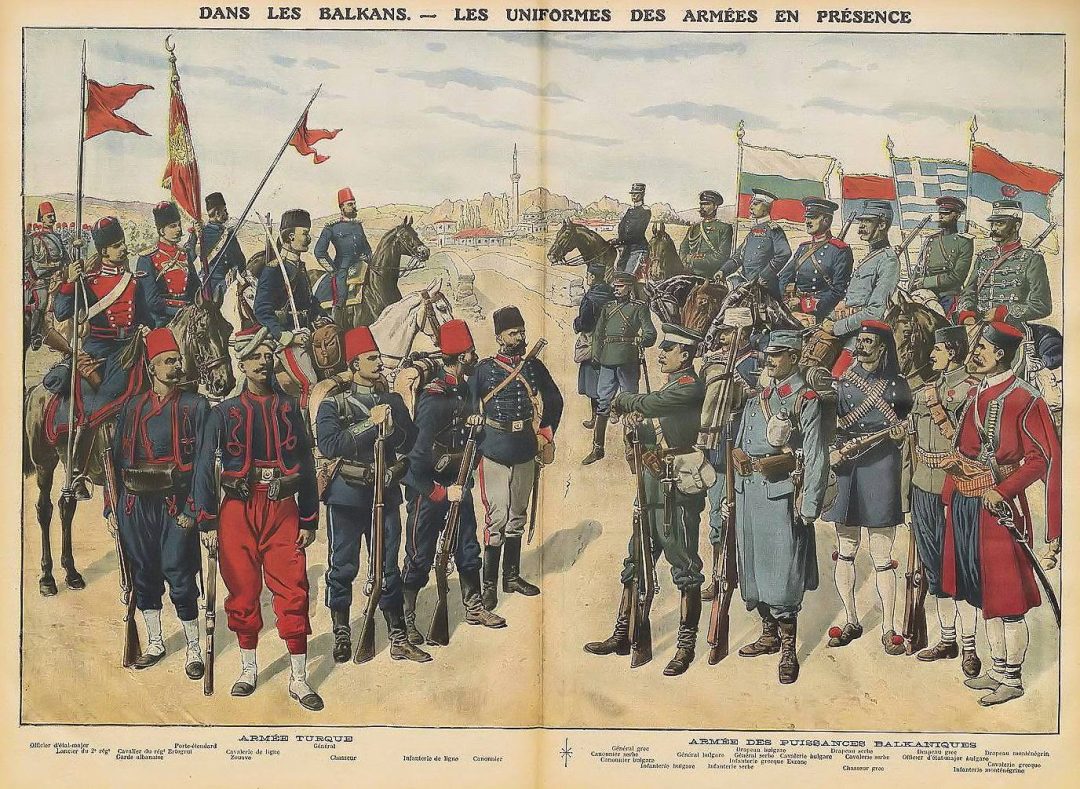

The Durrell Library of Corfu planned a symposium on this theme which was cancelled due to the pandemic. But we decided to gather the would-be participants into a book. The concept is rooted in the idea that, ever since independence, the Greek state has been encouraged to “look West” and to “modernise”. At the same time, the “Megáli Idéa” had the ambition of embracing Greeks who were not included in the original state, so that there was also a “look East” perspective. So there have always been two sides to history and, I think, at least two sides to the future.

Ion Dragoumis (1878-1920) warned that Greece should not give itself unconditionally to the West. He challenged the hegemony of the West, arguing that its principles and its sense of statehood were not entirely suited to Greek life. This was an excellent starting-point for our discussions. It led me to invite “expert witnesses” to two basic components of the book: issues which modern Greece might encouter in its increasing “westernisation”, and, in the widest sense, the cultural elements in Greek society which are non-western in origin.

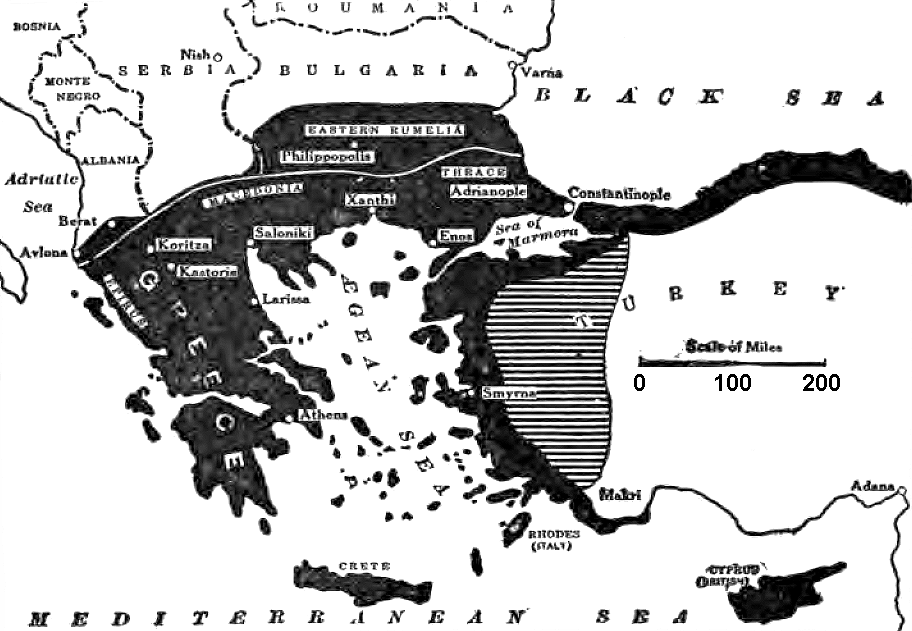

Furthermore, the modern state is founded on the principles of the European Enlightenment – a centralised nation-state which has been developed today into the idea of Europe as a single political and economic entity. I am not sure that this momentum towards a “Megáli Evrópi” is the most desirable direction for Greece, especially when, at the “sharp point” of the EU, its relations with Turkey, both historically and in the present, are so volatile.

This is underlined very strongly by Chloe Howe Haralambous who describes the reception of boatloads of refugees in Lesvos, which she calls “Restaging Thermopylae”. Here, the outsiders threatening Greece were not the refugees clamouring ashore, but the German NGOs which saw them not as personalities but as potential cheap labour for northern Europe. In this instance, Greece is poised dangerously between the west’s institutional perception of asylum seekers and the humanitarian compassion towards people from the east.

One thinks of the pithy observation of historian Arnold Toynbee: “‘Europe’ and ‘Asia’ are conventions which are only possible on a small-scale two-colour map.” Of course, in 1922, just before the Anatolian catastrophe, Toynbee also made the controversial statement “if being radically alien to Western civilisation is a valid reason for the expulsion from Europe of the Ottoman Empire, many other non-Western European states, beginning with Greece herself, will have to pack their bags.”

What do you believe is Greece’s legacy in the Levant? Is Greek presence still felt there in any significant way or is it more a thing of the past?

It is much more than a “legacy” because Greece and Greek ideas are a living presence in the Levant. When we consider that “Levant” and “Anatolia” are synonymous, meaning “the rising of the sun”, we can understand not only that it has a permanent place in the Greek heart and mind, but that Greece has an ongoing relationship with the Levantine region – with Cyprus, with Turkey, with Israel, with Syria, and as far south as Egypt.

For this reason, I invited essays on the destruction of Smyrna/Izmir, on the cosmopolitan character of Alexandria, and on the attraction of Theodorakis to the musical heritage of his mother’s Anatolia, and I had a conversation with Tassos Boulmetis about his 2003 film “A Touch of Spice” (Πολίτικη Κουζίνα) which has the deliciously ambiguous title – referring both to cuisine and the city (the “Polis”) where it originated. In the film, Boulmetis says “Our cuisine is tinged with politics. It’s made by people who left their dinner unfinished somewhere else.” That sense of incompleteness, that something vital is missing from Greek life if the “eastern” side of its culture is ignored or sidelined, is a central tenet of this book.

In addition, I asked Christy Lefteri. a Cypriot novelist born in London, to speak about her novel ‘A Watermelon, a Fish and a Bible’ which plants Cyprus centrally between Europe, Asia and Africa. The complexity of the situation in which she places her characters exemplifies both their personal dilemma and the cultural-political scenario in which history condemns them to live.

The Anatolian catastrophe had two major effects on life in Greece – both the mainland and the Aegean islands. Sociologically, it brought 1.5 million ethnic Greeks (who had never seen Greece) into the country where, as Tassos Boulmetis recalls, they were regarded as “Turks”. And in political terms, as Emilia Salvanou points out, it had a long-term effect in giving an impetus to the Greek Left, since the innately conservative nature of Greek society found it difficult to accommodate these newcomers in settlements like “New Smyrna”. And, as Neni Panourgiá (author of Dangerous Citizens) argues in her survey of the political and psychiatric uses to which Leros was put, institutional violence “keeps tightening the tension between east and west, between what is civilised and what is not”.

How is Greece connected to China, the Silk Road and other Asian countries like India?

The discussion by Sophia Kalantzakos of China’s growing presence in Europe, and especially Greece, emphasises that a major economic power, and a political force very different to our western sense of democracy, cannot be ignored. The fact is, since 2016, the Chinese shipping company Cosco has been the majority stakeholder in the port of Piraeus. Already, in 2014, Antonis Samaras could state that “Greece is the friendliest and most reliable country in Europe for China”, in the same breath as mentioning the possibility of establishing a Chinese naval base in Crete! This is truly a new dimension to the “eastern question”, if you like.

But we have to look back to ancient history to appreciate that there was a symbiosis between Greek and Indian philosophers, which isn’t widely appreciated and which isn’t obsolete – a transitus of ideas between east and west – where scholars are discovering more and more the relation between, for example, Pyrrho and Buddhism which could teach us much about ways of living and thinking today.

The title of your book is “Greece Between East and West: Culture and Geopolitics”. How do you view Greece’s geopolitical and cultural position now in Balkan region?

The Bulgarian novelist Kassabova, who is a good friend of the Durrell Library, has written deeply emotional, probing, books about the Albanian-Macedonian-Bulgarian-Greek region, a profound documentary on the history and culture of the region. To the Lake, in particular, is relevant to our discussions because it in fact discusses two lakes – Ohrid and Prespa – which are at the heart of Greece’s relations with the Balkans. Kapka permitted us to include a chapter from To the Lake which is meltingly compassionate and at the same time surgically analytical of the Greek-Macedonian-Albanian situation. I’m saying this because an artist like Kapka can so often point us towards lesions, lacunae and lymph nodes which politicians and economists would prefer to ignore.

“Westernisation” is also attempting to “cocacolonise” the Balkans, as if these countries bordering Greece (North Macedonia, Bulgaria, even Turkey, and Albania which I see everyday as I walk in the village where I live) are somehow culturally uniform. This is so far from reality that Greece Between East and West emphasises the complexity of the Balkan identities, which have such a deep connection with Greek identities, from the still Italianate Ionian islands to the Levantine islands of the Aegean. The sub-title of the book, “Culture and Geopolitics”, insists that you cannot separate these cultural identities, histories and futures from the geopolitical position in which Greece finds itself. It isn’t merely part of Europe/the EU. It has a future between east and west.

Is there still a cultural or ideological dilemma between “East and West” or has Greece (and the Greeks) definitely settled on the side of the West?

The sociological and cultural consensus of the contributors is that the political imperative to be “western” ignores many aspects of the “Greek spirit” which continue to sustain Greece’s ambivalent position between east and west. But, as Roderick Beaton, emeritus professor of Greek and an honorary citizen of Greece, says in his Foreword to the book, “This duality is not reducible to a single proposition. It is not ‘either/or’ but ‘both/and’.” This is what I believe, both pragmatically and passionately, about Greece, about the EU and about the Greek diaspora.

Finally, may I say that the last US ambassador, Geoffrey Pyatt, made a valuable point about Greece’s geopolitics: “if you draw a Venn diagram of this region, there are three circles which come together: one is the circle which, of course, comes with the security challenges that come out of Syria, Iraq, and the Eastern Mediterranean; another is a circle which reflects the security challenges arising from militarization of the Black Sea, [and] expands to Russia; and the third circle is that which reflects developments in North Africa. Where that Venn diagram comes together is right here with Greece. So we recognize that you are living in a very complicated neighborhood.”

“Complicated” is exactly the right word! I make a small joke about Greece’s – the fact that Greece is indeed “between east and west” and, as Beaton says, cannot be divorced from either.

* Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi

TAGS: MODERN GREEK HISTORY