Alexander Ypsilantis was one of the early heroes of the Greek War of Indepedence. As the leader of the secret organisation Filiki Eteria, he played an important role in planning and preparing the war against the Ottoman Empire, and his ill-fated campaign in the Danubian Principalities preceded and paved the way for the declaration of the Revolution in mainland Greece.

Family and early life

Ypsilantis was born in Constantinople on 12 December 1792 (N.S., 1 December O.S.) to a prominent Phanariote family. The Phanariotes –who took their name from Phanar, the Greek quarter of Constantinople– exercised great influence in the 18th-century Ottoman Empire as administrators in the civil bureaucracy.

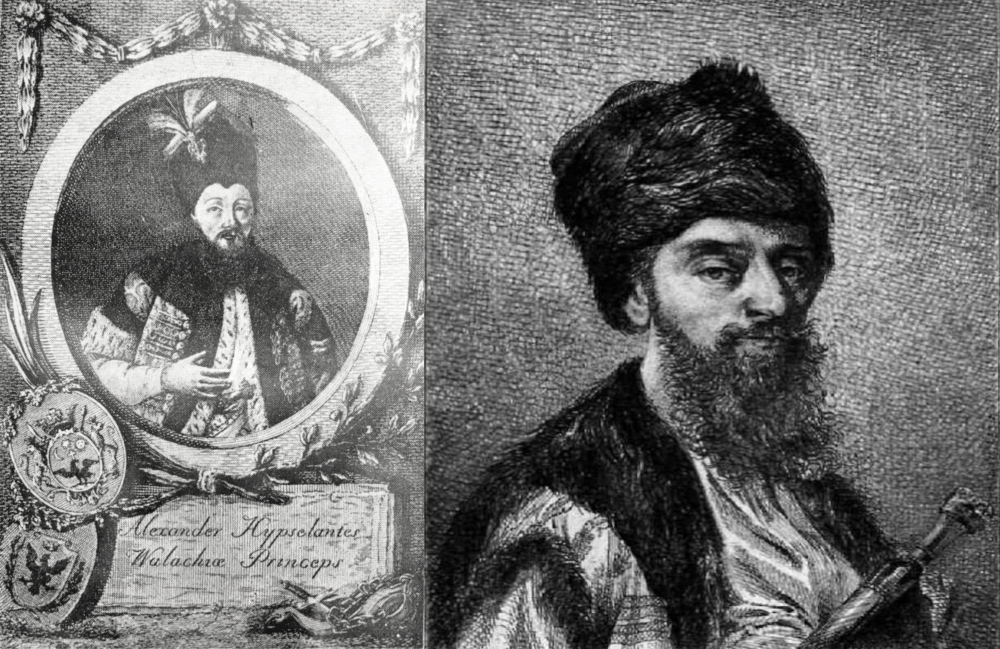

His grandfather, Alexander Ypsilantis (1726–1807), was a Greek Voivode (Prince) of Wallachia and Moldavia in the late 18th century. His father, Constantine (1760-1816), was Grand Dragoman of the High Porte (1796–99) and Hospodar (lord) of Moldavia (1799–1802) and Walachia (1802–06). His mother was Constantine’s second wife, Elisabeta, who came from the Văcărescu family, one of the oldest families of boyars (high-ranking nobility) in Wallachia.

Alexander was the eldest of seven children; two of his brothers would also go on to play an important part in the Greek War of Independence: Demetrios (1783-1832) as a military leader, who would be named field-marshal by Greece’s first head of state, Ioannis Kapodistrias, while Nikolaos (1796-1833) as the head of the “Sacred Band” at the fateful Battle of Drăgășani.

Left: Alexander Ypsilantis, Prince of Wallachia (via Wikimedia Commons); right: Constantine Ypsilantis, 1863 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Alexander Ypsilantis, Prince of Wallachia (via Wikimedia Commons); right: Constantine Ypsilantis, 1863 (via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1806, Constantine Ypsilantis was deposed as Prince of Walachia due to his involvement in the Russo-Turkish War of 1806–1812 on the side of the Russians; he escaped with his family to Imperial Russia, while his father, Alexander the elder, who lived in Constantinople, was arrested by the Ottoman authorities and executed. The young Alexander had received a thorough education, and was fluent in Romanian, Russian, French and German. He was presented to the imperial court in Saint Petersburg.

Russian military service

Upon graduating from military school, Ypsilantis entered the prestigious Chevalier Guard Regiment in April 1808 with the rank of cornet (second lieutenant), and was promoted to lieutenant two years later. He fought in the Napoleonic Wars (battles of Klyastitsy, Polotsk and Bautzen), reaching the rank of captain in 1813. He was transferred to the Grodno Hussar Regiment as lieutenant colonel; he lost his right arm fighting either in the Battle of Dresden or the Battle of Kulm, and was subsequently promoted to full colonel.

Having earned the sympathy of Tsar Alexander I, he was appointed as his aide-de-camp in early 1816. In late 1817, at the age of 25, he became a major general and commander of the 1st Brigade of Hussars of the 1st Hussar Division.

Left: Alexander Ypsilantis depicted in the uniform of the Grodno Hussar Regiment in which he served until 1817 and awarded the Order of St. Anne 2nd Class (22 January 1814), unknown painter, 1814-1817 (by 2gymkais2 via Wikimedia Commons); right: Portrait of Alexander Ypsilantis by Dionysios Tsokos, 1853, (National Historical Museum of Greece via Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Alexander Ypsilantis depicted in the uniform of the Grodno Hussar Regiment in which he served until 1817 and awarded the Order of St. Anne 2nd Class (22 January 1814), unknown painter, 1814-1817 (by 2gymkais2 via Wikimedia Commons); right: Portrait of Alexander Ypsilantis by Dionysios Tsokos, 1853, (National Historical Museum of Greece via Wikimedia Commons)

Involvement in the Filiki Eteria

The Filiki Eteria (also transcribed as Philiki Etaireia or Philike Hetaireia, meaning “Society of Friends”) was a secret organisation, founded in Odessa in 1814, that for years planned and then coordinated the launching of the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire. Following years of preparations, the founding members were looking for a respected and highly recognisable figure to take over the society’s leadership. They approached Count Ioannis Kapodistrias, de facto Foreign Minister of Russia at the time, who repeatedly refused, deeming the goal of Greek liberation honourable but entirely unachievable.

In 1820, the position was offered to Ypsilantis, who assumed leadership of the Filiki Eteria in April of that year (under the title of “Commissioner General”). He requested a two-year leave of absence from the Tsar and began active preparations for the revolution. In July 1820, he left St Petersburg to meet with the various branches of the Filiki Eteria in Moscow, Kiev and Odessa. In early October 1820, he called a council in Izmail (in Russian Bessarabia, modern-day Ukraine), to draw up a final plan for the revolution.

Τhey initially intended to begin the revolution in the Morea (historic name of the Peloponnese) in November or December, with another revolt breaking out in the Danubian Principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia), in the hopes of taking the Ottomans by surprise and driving them to split their forces – and ideally even managing to involve Russia in the ensuing conflict (since Ottoman troops were not allowed to enter the Principalities without Russia’s permission). However, they had to postpone the date for the spring of 1821.

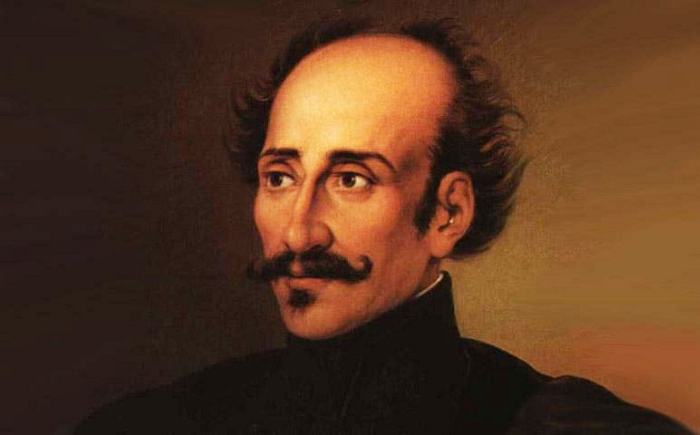

Alexander Ypsilantis in the Sacred Band uniform (detail), National Historical Museum of Greece

Alexander Ypsilantis in the Sacred Band uniform (detail), National Historical Museum of Greece

Uprising in the Danubian Principalities

In February 1821, there was fear that secret documents of the organisation had fallen in the hands of the Ottoman authorities. Ypsilantis thus decided to precipitate the uprising; on 22 February (O.S.) accompanied by several other Greek officers in Russian service, Ypsilantis crossed the Prut river at Sculeni and marched into Moldavia.

Two days later, on 24 February (O.S.), he raised the first flag of the Greek Revolution at Iaşi and issued a proclamation titled “Fight for faith and country“, a passionate call to arms addressed to all Greeks; in it he claimed that the insurgents were battle-ready, that they had the support of the Serbs, that the “enlightened peoples” of Europe favoured their struggle for freedom and that “a major power” would also defend the rights of the Greeks, clearly alluding to Russia.

The flag of the Revolution used by Alexander Ypsilantis; it was based on a design by Rigas Velestinlis, bearing a phoenix bird and the motto “From my ashes I am reborn” (by Philly boy92 via Wikimedia Commons)

The flag of the Revolution used by Alexander Ypsilantis; it was based on a design by Rigas Velestinlis, bearing a phoenix bird and the motto “From my ashes I am reborn” (by Philly boy92 via Wikimedia Commons)

Count P. D. Kiselyov, then Imperial Russia’s chief of staff of the Second Army in the Ukraine, would write in a letter, “Ypsilantis, in crossing the frontier, has already given his name to posterity. The Greeks, reading his proclamations, will cry and flock under his banner in jubilation.” In a letter to the Tsar, Ypsilantis submitted his resignation from the imperial army and requested the Russian Emperor’s support in the upcoming war.

In March 1821, Alexander Ypsilantis would found the Sacred Band (Hieros Lochos, named after the Sacred Band of Thebes, an iconic troop of select soldiers in Ancient Greece), the first organised military unit of the Greek War of Independence, formed by volunteers, mainly university students from the Greek communities of Moldavia, Wallachia and Odessa. This was the core of his army, which comprised about 8,000 men, including 2,500 cavalry and 4 cannons.

However, Ypsilantis’s plans did not progress as envisaged; on hearing about it – while at the Congress of Laibach– the Tsar unequivocally condemned the revolt in the Danubian Principalities, and asked Ypsilantis to back down. Russia observed a strict neutrality, refusing any direct or indirect support to the revolted Greeks, and allowed Ottoman troops to enter the Principalities. Besides, soon thereafter, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople was forced by the Ottoman authorities to excommunicate the revolutionaries, under the threat of a massacre of the city’s Greek population – which would not, nevertheless, be averted.

Left: Bust of Alexander Ypsilantis in Nea Trapezounta, Pieria (by Lemur12 via Wikimedia Commons); right: Alexander Ypsilantis crosses the Prut River, by Peter von Hess (by Clipclap24 via Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Bust of Alexander Ypsilantis in Nea Trapezounta, Pieria (by Lemur12 via Wikimedia Commons); right: Alexander Ypsilantis crosses the Prut River, by Peter von Hess (by Clipclap24 via Wikimedia Commons)

Ypsilantis’s efforts to attract other Balkan Christians to his side also proved fruitless. He had hoped to join forces with the Wallachian Pandours, a group of irregulars who planned a revolt in Wallachia; the Filiki Eteria had initiated contacts with Tudor Vladimirescu, the leader of the Wallachian uprising which would eventually break out in early 1821. But Vladimirescu was intent on directing his revolt solely against the ruling class of the Hospodars rather than seeking a nationalist awakening, and thus the alliance fell through. Serbians were also reluctant to become involved in hostilities with the Ottomans without support from Russia, while the absence of the anticipated Russian support would soon also make the boyards of Moldavia turn against Ypsilantis.

Ottoman troops entered the Principalities in April, with Russia’s consent. The first large-scale conflict between them and the Sacred Band was at Galați (in Western Moldavia), where the Greeks lost and the town was subsequently sacked. The volunteers were largely untrained and many started to desert following the massacre as well as a series of internal disputes. In May, there were further hostilities between Greeks and Ottomans, with no positive outcome on the Greek side.

The largest engagement took place on 7 June (O.S.) at the Battle of Drăgășani. The Ottoman troops were camped near the city of Drăgășani in Wallachia, and Ypsilantis planned on leading an offensive against them with the entirety of his forces. However, cavalry captain Vasilios Karavias led his men into an unplanned attack; the Sacred Band, headed by Nikolaos Ypsilantis, hurried to their aid, and were thus exposed and almost completely annihilated. The battle ended in a crushing defeat for Ypsilantis’s army, practically signaling the end of the revolution in the Principalities. The army gradually dispersed and Ypsilantis himself retreated to the nearby Râmnicu Vâlcea.

Burial monument of Alexandros Ypsilantis at the Pedion tou Areos (by 2gymkais2 via Wikimedia Commons)

Burial monument of Alexandros Ypsilantis at the Pedion tou Areos (by 2gymkais2 via Wikimedia Commons)

Imprisonment and death

After waiting for a few days to be granted entry into Austro-Hungarian territory, Ypsilantis, along with a few of his followers, finally decided to cross the border but was subsequently arrested by the Austrian authorities as the head of an illegal insurgence. He was imprisoned for seven years in Terezín (in modern-day Czech Republic).

Following his release in November 1827, he retired to Vienna, where he died in extreme poverty two months later (19/31 January 1828) at only 35 years of age. It is believed he suffered from muscular dystrophy. As per his final wish, his heart was removed from his body after his death, and sent to Greece a few years later; it is now located at the Pammegiston Taxiarchon Church of the Amalieion Orphanage in Athens.

His body was buried at St. Marx Cemetery in Vienna; his remains were transferred by members of his family to the Ypsilanti-Sina estate, Schloss Rappoltenkirchen, in Austria in 1903. In 1964, they were transferred once more to the Pedion tou Areos in Athens, a public park dedicated to the heroes of the Greek War of Indepedence.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Ioannis Kapodistrias, Modern Greece’s first head of state; Theodoros Kolokotronis: The archetypal Greek hero; 3 February 1830: Greece becomes a state; Pedion tou Areos – A park dedicated to the heroes of the Greek Revolution of 1821; POEM OF THE MONTH: “Riga’s Last Song” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

N.M. (Intro image: Alexander Ypsilantis in the Sacred Band uniform (detail), National Historical Museum of Greece)

Sources

Bitis, Alexander, 2000, The Russian Army and the Eastern Question, 1821-34. PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science

Foundation of the Hellenic World, 2000, “The formation of the Hellenic State 1821-1897“