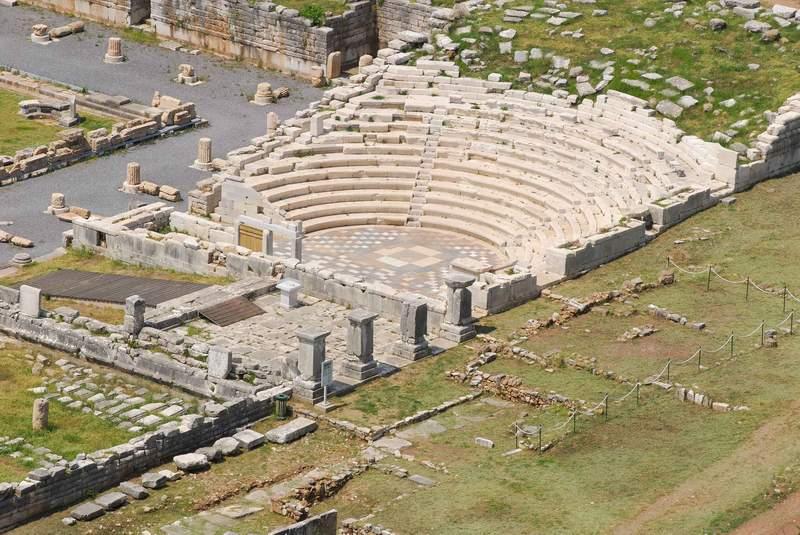

Aiming to shine a spotlight on Greece’s lesser-known ancient theaters, a new cultural initiative has been launched by the Diazoma association and the National Theater of Greece, in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture. The project, supported by a 100,000-euro grant from the ministry, seeks to introduce the public to lesser-known ancient theatres around Greece through a contemporary staging of Aristophanes’ comedy “Plutus.”

From July to September, audiences across Greece will have the unique opportunity to experience “Plutus,” the last surviving work of Aristophanes, in its latest version. The play has been translated by Dimosthenis Papamarkos and is directed by Manos Vavadakis. The production features a talented company of new-generation Greek actors, bringing fresh life to the classic comedy.

The tour will visit 16 ancient theaters, allowing the public to appreciate these cultural treasures in their natural, open-air settings, and enjoy “Plutus,” which elegantly crowns the poet’s experimentation with the comic genre, in natural light and sound.

The participating ancient theaters include:

- Kabireion, Thebes

- Demetria, Volos

- Maroneia, Rhodope

- Mieza, Naoussa

- Gitana ,Filiates, Thesprotia

- Cassope, Preveza

- Amvrakia, Arta

- Pleurona, Messolonghi

- Aigeira, Aigio

- Ecclesiasterion, Messene

- Ancient Theatre of Gythio, Gythio

- Ancient Theatre of Arcadian Orchomenos, Tripoli

- Ancient Theatre of Eretria, Eretria

- Ancient Theatre of Orchomenus , Boeotia

- Ancient Theatre of Zea, Piraeus

- Ancient Theatre of Thoricus, Lavrio

The Central Archaeological Council (KAS) has granted unanimous approval for these 16 venues to host the performances of Aristophanes’ comedy; the approval comes with the stipulation that no fees or tickets will be required for the performances, aside from standard admission to the archaeological sites where the venues are located. The schedule of the program running from July to September was presented at a press conference at the National Archaeological Museum, during which, minister of Culture Lina Mendoni emphasized the importance of integrating cultural heritage into citizens’ daily lives. “Our inventory of monuments is neither static nor simply a part of a tourism product. A cultural inventory is something very important because of the values it carries, and that is why it should be a part citizens’ daily lives,” the minister said. She highlighted that the ministry’s policy since 2019 has been to open archaeological sites and monuments to use for modern plays and performances, noting that cultural heritage is a source of energy and inspiration for modern creativity.

National Theater’s Artistic Director Yannis Moschos, expressed excitement about the institution’s new venture into lesser-known territories. “Our company will find itself for the first time in its history in new places, while local communities will come into contact with the activity of the National Theater,” Moschos said. He noted that the troupe performing “Plutus” comprises younger generation actors from the National Theater, offering new artists the opportunity to engage with ancient drama and present Aristophanes through a contemporary lens.

Stavros Benos, founder the Diazoma association for preserving ancient theatres and former minister of Culture called the program “a triumph of synergies” and said that in its 15-year existence, Diazoma has showcased and to studied a total 0f 50 ancient theatres around Greece «in order to unlock European (funding) programs” for their preservation. Benos noted that the maturity and funding of each project occurred in record time, demonstrating the effectiveness of collaborative efforts.

Free passes for the performances, with the exception of venues requiring paid entrance, will be distributed two hours before each show. Detailed information on dates and times is available on the National Theater’s website.

This initiative not only aims to promote Greece’s rich cultural heritage but also fosters a deeper connection between local communities, modern audiences and ancient drama, ensuring the timeless works of Aristophanes continue to resonate with new generations.

About Plutus

Old Chremylus goes to the oracle of Delphi to ask Apollo if he should raise his son by teaching him the value of injustice, thereby ensuring his future prosperity. The god does not answer directly, but urges him to follow the first person he sees when he leaves the temple. Taking Apollo’s advice, Chremylus finds himself hot on the heels of an old blind man. With the help of his slave, Carion, he discovers that the man is actually Plutus, the god of wealth. Chremylus plans to cure Plutus’s blindness with the help of the god of healing, Asclepius, so that he can fairly distribute his gifts to the virtuous citizens. The goddess of poverty, Penia, who has championed the city until now, tries to stop them, reminding Chremylus – but also the audience – of the need and value of a life lived in moderation. However, Penia will lose the argument hands down.

Asclepius performs his miracle and Plutus regains his sight, and with it his wits. Chremylus’s house is packed with visitors who want to meet his guest. The new situation has not only changed the balance of society but has also brought disruption to Mount Olympus. Hermes, the messenger of the gods, has no work, and asks for help from Plutus, while the priest at the temple of Zeus is starving because the Athenians have stopped making sacrifices to the god. Finally, good sense prevails and Plutus, accompanied by the Chorus, is led back to his old home, at the back of the temple of Athena in the Parthenon, where the city’s coffers are kept.

Plutus (338 BC), the last of Aristophanes’ surviving comedies, abandons the structure and motifs of Old Comedy, marking a shift to New Comedy. Aristophanes removes the choric interludes, the parabasis (addressing the public directly) and the derisive jokes from his play, turning his attention to the problems of everyday life.

Director’s note

The blind god, Plutus, regains his sight and shares the wealth equally in society. An early socialist or just nostalgic for a lost golden age? The play, written in 388 BC, after the defeat of Athens in the Peloponnesian War, suggests another Aristophanian utopia. But is a society whose material needs are fully met a happy one? Does individual prosperity precede social well-being? When is one truly free? When do the bonds of happiness break?

In this late-period play, the presence of the Chorus is negligible; it is a simple observer of developments. A Chorus that is absent is symbolic of a city that is indifferent. A small company of actors travels around Greece, inviting audiences to a new gathering in places where society once went for entertainment, debated, and made decisions. It invites us to listen together, to laugh together, and ultimately to return to being together, abandoning technological (or any other kind of) loneliness.

Read also from Greek News Agenda

- The Ancient Theater of Cassope opens to the public after 21 centuries

- The Cultural Route of the Ancient Theatres of Epirus

- Dimosthenis Papamarkos: “I would like to see more works of the fantasy, sci-fi, and horror genre in Greek literature”

I.L., with information from AMNA-MPA and the Greek National Theatre

TAGS: ANCIENT GREECE | ARTS | HERITAGE | THEATRE