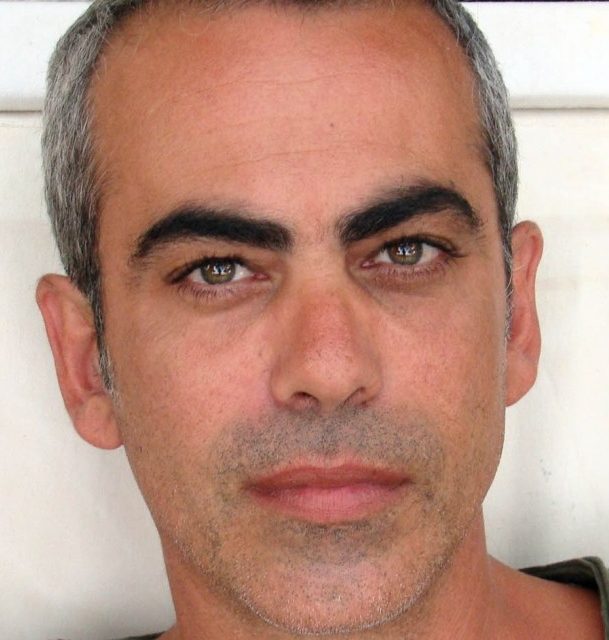

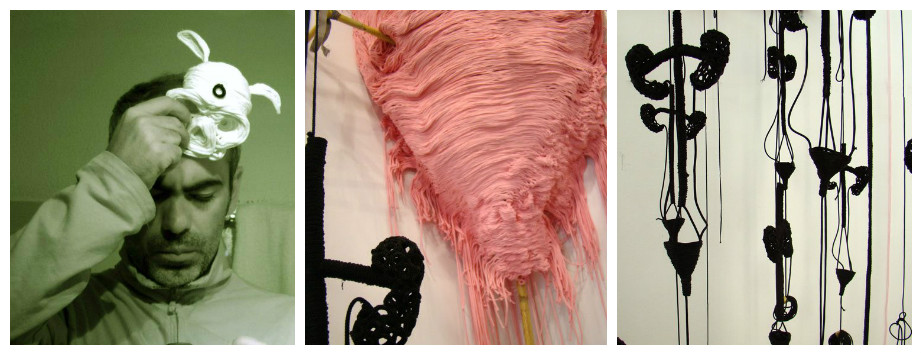

Alexandros Psychoulis, Greek artist and Associate Professor at the University of Thessaly, showcases his new work in the exhibition “Collective Dizziness Protocol” running at Zina Athanasiadou Gallery (Thessaloniki, November 18- December 10, 2016).

Alexandros Psychoulis** spoke to Greek News Agenda* about his new work which deals with the idea of symbiotic bliss based on his research of the “tsipouroposia” custom (the consumption of tsipouro in taverns) in his home town, Volos, as well as the new Postgraduate Program “Post-Industrial Design: Design and Artistic Practices for the Production of Everyday Life” which he co-directs with architect Zissis Kotionis, at the University of Thessaly.

He also shared his views on the relationship between collective and individual happiness and the reasons why one chooses to become a visual artist.

How did it all start? When did you realize that you want to become an artist?

My father was a chemist and a painter; my mother also painted, as a hobby. Together, they ran a gallery in Volos. Painting was like a game for me. When I realized, later on, that I could also study painting or become a professional artist, I felt I was a lucky man. To this day, my involvement with art is nothing but that game of my childhood years. Sometimes I feel as if I’ve tricked everyone and that I’ve never grown up.

You are show great diversity as an artist, as you’ve experimented with various artistic practices, from painting to theatre. After all of these years, would you say that you can now identify with one particular form of art?

I was always one of those people that wanted to try everything, whose parents and teachers usually try to admonish by telling them: “Don’t do many things, focus on one and do it well.” If this advice is not merely an ideological construct, it is certainly a dull recipe. I never tried to prove that one can do a lot of things and do them well, but that everything – that is, “many” things – is one: That different artistic expressions are under the surface associated with the same rules.

I consciously use a different discourse depending on the subject I am exploring. Different subject matters lead to different media. I walk this path with determination, telling myself that I have a commitment towards others, my students and children who enjoy digging, full of guilt, into different things. I hope that, someday in the future, parents will say: “If you want, go ahead and do many different things; you do not need to become a virtuoso, but to tell your own stories in the most honest way.”

Can you tell us more about the concept of your new work “Collective Dizziness Protocol“? What was it that sparked your interest to explore this issue?

Can you tell us more about the concept of your new work “Collective Dizziness Protocol“? What was it that sparked your interest to explore this issue?

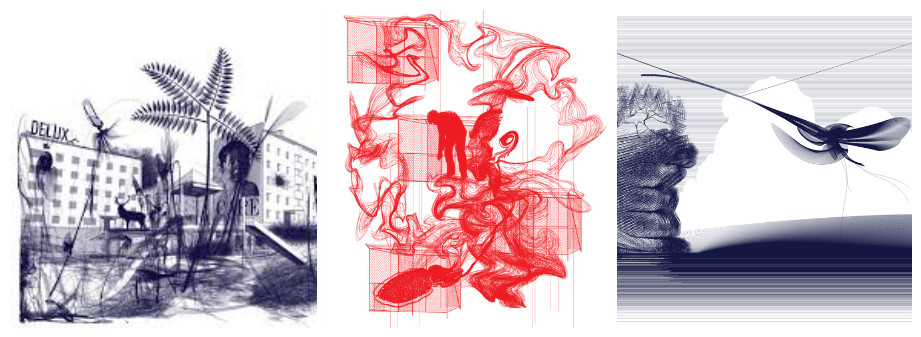

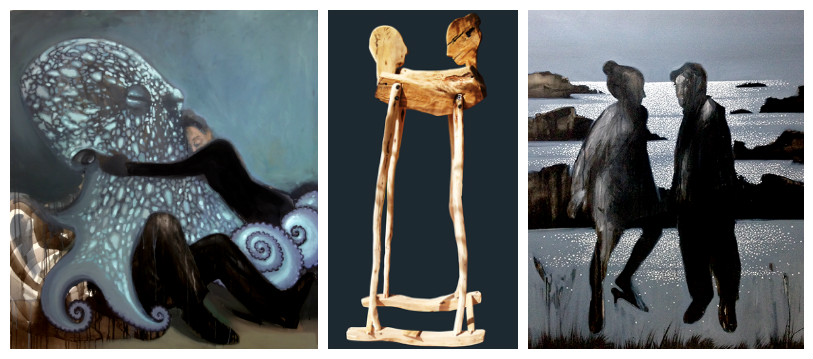

The starting point of this exhibition is the participation and the subsequent observation of a particular culinary tradition, that of “tsipouroposia”, namely the consumption of tsipouro in the taverns of Volos (the so called “tsipouradika”). It is a unique banquet experience that brings people to a state of camaraderie, tranquility and brief happiness. But not always; in order to have the above results, nine conditions must be met, which I first elaborated in detail, by watching and analyzing the types of this ritual as it evolved in the city, in the course of a hundred years. What cannot be expressed in words is approached with drawings, paintings and sculptures.

The idea of collective happiness is interpreted and attained in different ways across cultures throughout the world. In your view, how important is collective happiness for the Greeks and how is it related with individual happiness?

Starting with the second part of the question, I would say that happiness is never a personal matter. Happiness that cannot be shared is at the same time misery.

One will find that people all around the world pretty much congregate in gatherings that unwind and bring bliss to participants as they collectively take a step beyond their daily reality. If we look at “tsipouro adulation” as a relatively new “ritual” and take a leap comparing it with the tea ceremony in China and Japan – rituals whose roots go back many years – we’ll be faced with two completely different cultural approaches. For instance, in the Japanese tea ceremony, the objective is to reach a “symbiotic bliss”. In the “tsipouroposia” in Volos and not only there, one will realize that the result is the unconditional identification in mind and spirit with the others.

Whilst the Greeks are part of western society and culture, they will never give up, on account of temperament and inherited wisdom, their blissful gatherings in the name of overproduction.

You are also an Associate Professor at the Department of Architecture in the University of Thessaly. Was teaching a conscious choice through which you felt you can express yourself, as well as to give-and-take things or one of necessity as a means of earning a livelihood?

You are also an Associate Professor at the Department of Architecture in the University of Thessaly. Was teaching a conscious choice through which you felt you can express yourself, as well as to give-and-take things or one of necessity as a means of earning a livelihood?

I began teaching at the University of Thessaly at the age of 34 – that is, quite early in my life. However, I recall having already begun feeling not so “young” anymore. What I’m saying is that my approach to life had begun being utterly “rational”; the time of questioning had faded, my rage had subsided.

So, I thought that if I started teaching at the University, I could “steal” some of the students’ anger. But things didn’t exactly turn out that way. Times had changed for good. Both my students and I had to create the mood for change in academic terms and not to expect it as a natural impulse.

You are co-director of a new Postgraduate Programme on “Post-Industrial Design”. Does such a thing exist in Greece today, and if so, in what form? What is, in general terms, the relationship between design and fine arts?

In a discussion with the architect and writer Zissis Kotionis, who also teaches at the University of Thessaly Architecture Department, we concluded that – contrary to what happens with industrial design – having a postindustrial approach to design is something that could have a huge range of applications in Greece.

You see, postindustrial design focuses on small scale of production; it redefines the model of production of traditional techniques and is inspired by them so as to even arrive at a singular object, the “transcendental” or “non-utilitarian” object, what we recognize as a work of art.

Despite being one of the most prolific contemporary artists, with many solo and group exhibitions in Greece and abroad, you have stated that “there is no such thing as a career in Greece for visual artists”. What do you mean by that, does it relate to the crisis? If this is true, what are the motives for one to become a visual artist?

Despite being one of the most prolific contemporary artists, with many solo and group exhibitions in Greece and abroad, you have stated that “there is no such thing as a career in Greece for visual artists”. What do you mean by that, does it relate to the crisis? If this is true, what are the motives for one to become a visual artist?

The idea of a career as a visual artist in Greece has always seemed like a joke. The Greek state has always been promoting and capitalizing on our ancient Greek heritage, but not contemporary art production; fortunately we’ve never had in Greece the so called “Art Stock Market”, which operates with celebrities.

The crisis simply added the final nail to the coffin even of those artists who had some commercial success.

In Greece, you don’t get involved with Art so as to have a career, become rich or famous. You know this as a fact from the very beginning. From an early stage you look at the future and see the difficulties rising like a mount. If you can give it all up, you do so. If you can’t – if you believe that this form of expression is the only thing that makes you happy- you go on. You become a visual artist because you cannot do otherwise.

* Interview by Eleftheria Spiliotakopoulou

** Alexandros Psychoulis was born in Volos in 1966 and studied Painting at the Athens School of Fine Arts. He is also an Associate Professor of “Art and Technology” at the Architecture Department of the University of Thessaly, Greece and co-director of the new Postgraduate Program “Post-Industrial Design: Design and Artistic Practices for the Production of Everyday Life.

** Alexandros Psychoulis was born in Volos in 1966 and studied Painting at the Athens School of Fine Arts. He is also an Associate Professor of “Art and Technology” at the Architecture Department of the University of Thessaly, Greece and co-director of the new Postgraduate Program “Post-Industrial Design: Design and Artistic Practices for the Production of Everyday Life.

In 1997, he was awarded the Benesse Prize for his work “Black Box”, with which he participated in the 47th Venice Biennial. The exploration of virtual reality territory has been up until now the central drift of his work, which consists of installations, animation and painting, while in his most recent works the element of manual work is also present. He has presented many solo exhibitions such us: “God’sNails” (a.antonopoulou.art Gallery, Athens, 2012), “Under the shadow of Ailanthus Altissima” (Zina Athanassiadou Gallery, Thessaloniki, 2010), “Body Milk” (a.antonopoulou.art Gallery, Athens, 2003) and “There’s no place far enough for you to escape from images and the pain they caused you” (Deitch Projects, New York, 1998).

He has taken part in many group exhibitions, the most important of them being: THE LUMINOUS INTERVAL, Guggenheim Bilbao (2011), THE ARK, Old seeds for new cultures, 12th Biennale International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia (2010),Expanded Ecologies/ Perespectives in a Time of Emergency, National Museum of Contemporary Art EMST, Athens, (2009), Transexperiences, Greece (2008), 798 Space, Beijing (2008), Exploring cultural means to combat global homogenization, Foukoutake Hall, Tokyo University (2008), MASQUERADES/ femininity, masculinity and other certainties, State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki (2006), Positive Charge, State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessalonikι (2006), BIDA Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki (2005), Body Works Art Centre of the Municipality of Nicosia, Cyprus (2004), BREAKTHROUGH!, Greece 2004, Contemporary Perspectives in Visual Arts, Alcala, Madrid (2004), ϋber MENSCHEN, “Synopsis 1- Communications” Contemporary Art Museum, Athens (2000).

TAGS: ARCHITECTURE | ARTS | DESIGN | EDUCATION | FESTIVALS | GLOBAL GREEKS | LIFESTYLE