Dimitris Kountouras is a musician and musicologist, specializing on early music instruments (traverso, recorder) and the historical performance practice of early music. He is the director of the early music ensemble Ex Silentio and appears often in concerts with bayanist Konstantinos Raptis (as Duo Goliardi) and the Athens Camerata. He has given concerts as a soloist and chamber and orchestral musician at Sala Verdi in Milan, the Pablo Casals Hall in Tokyo, Megaron in Athens, the Konzerthaus in Vienna, the Styriarte festival in Graz, the J.S. Bach festival in Riga etc. He has recorded works for music labels Carpe Diem and Talanton with Ex Silentio, and played in baroque opera recordings for MDG and DECCA Classics.

His ensemble Ex Silentio (with Theodora Baka, Thimios Atzakas, Elektra Miliadou, Andreas Linos, Tobias Schlierf and Nikos Varelas) has performed widely at festivals in Sweden, Germany, Austria, Holland and Italy. Their latest recording, titled MNEME, won the PIZZICATO magazine Supersonic prize and was shortlisted for the prestigious International Classical Music Awards (ICMA) in the Early Music category in 2016.

Kountouras has published articles on early music interpretation, text and music relationships in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. He teaches historical flutes, chamber music and early music performance practice at the University of Macedonia, the Athens Conservatoire, the Filippos Nakas Conservatory and the Aghios Lavrentios Music Village. He spoke to Greek News Agenda* about the work of troubadours in the Latin Empire of Constantinople, how Greek music fits in the eastern/western music framework, the common elements of Mediterranean music and the unique profile of Greek instrumentalists.

Tell us about your latest research on the passage of troubadours trough the territory that is now Greece, during the time of the Crusades. What does your research show as regards the multicultural character of the region?

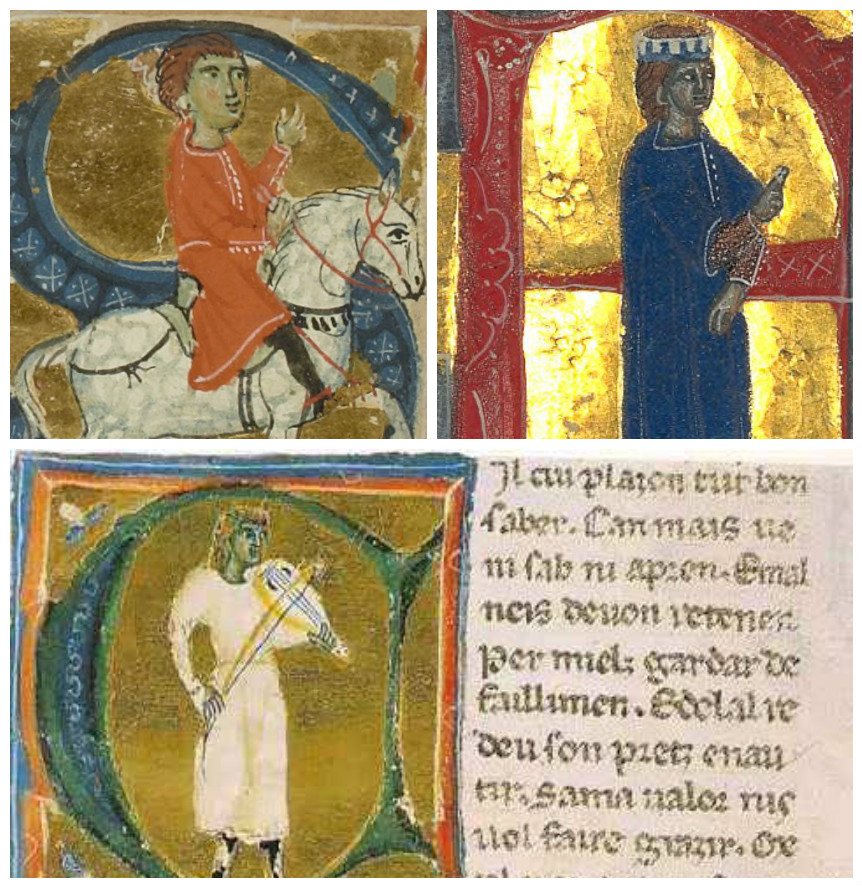

The idea for the project “Music and poetry of the troubadours in the Latin Kingdom of Thessalonica after 1204” came up a few years ago, when I was studying the life and work of French troubadours Raimbaut de Vaqueiras and Elias Cairel, who passed through the Greek world after joining the 4th crusade. These troubadours, along with fellow Frenchman epic poet Conon de Béthune, lived for a while in the Latin Empire of Constantinople, the feudal Crusader state founded on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire.

So, while the events of the 4th Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople by the crusaders in 1204 are well known, little is known about the activity of these troubadours who accompanied the Crusader Kings to Byzantium. We don’t know much about their life while in the East, or how their work influenced cultural life in the newly formed Latin Empire of Constantinople.

These two troubadours, Raimbaut de Vaqueiras and Elias Cairel, followed the new king of the Kingdom of Thessalonika to the city and resided there for some of their more creative years, leaving music and poetry of high quality and rich historical references. Studying their work helps shed light on the life and art of early 13th century Thessalonika, as well as on possible interactions between these Latin musicians and Greek-speaking artists of the time.

What is the relationship between “eastern” and “western” music? The latest work of your group Ex Silentio bridges these worlds by approaching Mediterranean music through early music.

In Europe, as compared to the East – in this case, the Near East and the Arabic world – polyphonic forms were developed quite soon, at least as far as court music is concerned, while in Eastern musical culture, monophonic idioms endured longer in court and in popular music. Ιn Europe, there was a lot of focus on forms, complicated structures and harmony, while in the East there was more emphasis on the melodic material and the singing quality of modal music.

Despite different national and cultural backgrounds, there are various things in common in all the musical traditions of the Mediterranean basin; this is what we tried to uncover and showcase in our Mneme CD, starting from the Arab-Andalousian tradition of Spain, continuing onto Catalonia, Provence, Italy, Greece and the Sephardic tradition of Salonica. In order to highlight these connections, we focused on monophonic repertoire, troubadour singing and instrumental dances from East and West, as well as known Greek traditional songs (such as To Kastro Tis Astropalias). A common element between traditional Mediterranean and early music are lengthy verses, something we highlight by interpreting these traditional songs as medieval, long, rhapsodic sagas.

Where would you classify Greek music in an eastern/western framework? Do Greek musicians have something unique to offer to the world?

Greece has been always influenced by both European and Eastern music; since 1850, Greek music was also strongly influenced by the rich Italian musical and theatre culture. Nowadays, it is striking how many different musical styles one can find in Greece: traditional and popular music, classical and early music, Balkan jazz and impro. It is fascinating that all these styles coexist in harmony and form an organic part of contemporary Greek music culture. So, in Greece you will find musicians playing all kinds and styles of music, just like in Europe. What´s more, lately, we are witnessing increasing activity in classical music, as well as in improvised and even in early music.

There is often an interesting background in some Greek musicians, as they combine a western/classical music education with oral/traditional music experience and training. The survival and diffusion of traditional music in Greece is something unique: there is nothing akin to that in western or central European countries. That profile certainly gives an interesting and open minded approach to music making.

Furthermore, more and more Greek instrumentalists have experience and training in both classical and traditional instruments, by and large due to the special High Schools in Greece specializing in a musical curriculum. This development is quite recent, as the institution of musical High Schools was established only 20 years ago, but I find it can definitely give intriguing and unexpected results.

*Interview by Ioulia Livaditi