Dinos Kogias was born in 1964 in Karlovasi, Samos. He lives and works as a lawyer in Athens. He collects, researches and writes about modern Greek, Ottoman and Balkan ceramics. He is a founding member of DIKTIO, a Southeast European ceramics research group, and regularly participates in related international symposia. He has published two books on his home island of Samos: Samos 1862-1920 photos and postcards and The tram at Karlovasi, Samos (1905-1939), while his study of Samian pottery of the 19th and 20th centuries is forthcoming.

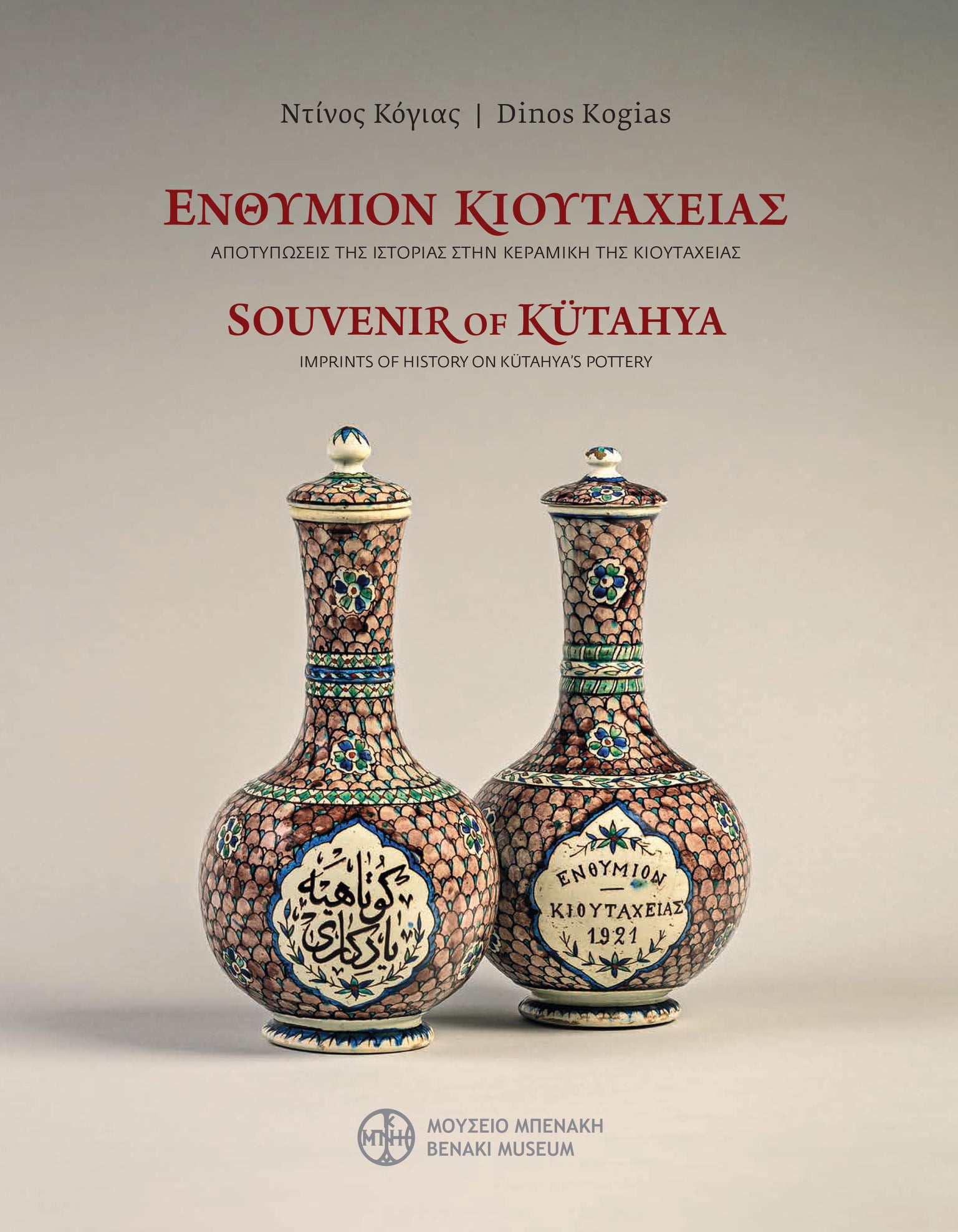

Your book Souvenir of Kütahya depicts various unknown aspects of Kütahya (late 19th century-early 20th century). Tell us a few things about this writing venture.

In this book, I have sought to place the ceramic production of Kütahya in the historical and social context of this turbulent period, so that the reader may gain a broader picture beyond the limited perspective of style and technique. Research focuses on microhistory. It searches in the ceramics of Kütahya the imprint of major historical events of the time, such as the Greek-Turkish war of 1897, the Balkan Wars, the Constitution of 1908. It records, for the first time, the contribution of the Greek Orthodox community to the ceramic history of the city, as well as the pottery production during the period of the town’s occupation by the Greek armed forces from July 1921 to August 1922. During the fifteen months of the Greek occupation of Kütahya, the production of pottery, which had been interrupted because of the war, resumed and a large number of items ended up in Greece, mainly brought back by Greek servicemen. Many of these ceramics bear Greek commemorative inscriptions with the initials or even full names of their first owners, and accordingly serve as important historical evidence of specific social and cultural referents.

Yet research is not limited to 1922. It follows the violent disruption of a centuries-old coexistence of the three largest communities of the city, which forever lost is multicultural and multi-ethnic character due to the war. It follows the refugee potters, Greek and Armenian, of Kütahya, in Greece and Jerusalem and highlights the influence of the Ottoman decorative repertoire in new socio-economic and cultural environments. Finally, it returns to Kütahya to record the revival of ceramic art by Muslim potters in the early years of the Turkish Republic. Although the book is not historical, history is present on its every page.

The collection of artefacts and archival material began systematically about 17 years ago thanks to the acquisition of some ceramics with Greek inscriptions from Kütahya. I knew of the existence of such pottery from fragmentary references in older publications. But when I held them for the first time in my hands I realized that they are a special kind of ceramics, important artefacts of a historical and collective past that we have now forgotten or simply are not familiar with.

It was a subject that had concerned little, if any, researchers and, of course, was completely unknown to the general public. The peculiarity of commemorative ceramics with Greek inscriptions is that they constantly produce new narratives and at the same time act as a guide to access the past, giving history a human face anew. Most of them depict the peaceful experiences of the Asia Minor warriors on the sidelines of all kinds of heroic deeds. They reproduce specific emotional worlds of their original owners and remain conveyors of ancestral memory for generations to come.

Such research required, in principle, the identification and study of a sufficient number of objects from this period, mainly in private collections, since few such ceramics are exhibited in museums or other permanent exhibitions. Of course, research also extended to long periods before and after the Greek occupation of Kütahya, during which very interesting samples of ceramics of historical and political interest were recorded. Along with the collection of ceramics, there was also collected corresponding photographic and archival material. During my research, I consulted all the known Greek and foreign bibliography related to Ottoman pottery, and especially that of Kütahya, while I resorted to historical books, newspapers, personal diaries of soldiers, trade guides and of course to the internet. Valuable information was obtained from the archives of the Directorate of Army History of the Hellenic Army General Staff and the Historical Archive of the National Bank of Greece.

Your study of Samian pottery of 19th and 20th centuries is forthcoming. How did your involvement in modern Greek, Ottoman and Balkan ceramics start?

I was born and raised in Karlovasi, Samos, an island in the Northeastern Aegean. As a student at Athens Law School, in the early 1980s, I started collecting material (mainly photographs, postcards, cigarette boxes and documents) from my homeland. The result of this collecting effort was the publication of two books: an album titled Samos 1864-1920 with extensively annotated photographic material and a study on the history of the horse-drawn tram that Karlovasi had under the title The tram at Karlovasi Samos, 1905-1939. My interest in the local history of the island brought me into contact with its ceramics, which are present in almost all of the island’s houses, but no one had ever bothered to record their history.

Samos has a rich pottery tradition which in modern times dates back to at least the 17th century. At the turn of the new millennium, I began to search for and collect material on Samian pottery. I interviewed the last craftsmen and sought out the descendants of those who had passed away. Systematic research followed in hegemonic and private archives, notarial documents, register books, newspapers, magazines, while at the same time I was collecting Samian ceramics. In this kind of research, the study and recording of the objects themselvesis extremely important and necessary.

So, gradually, I entered the world of pottery. I began delving into Greek, Ottoman, Balkan and European pottery from the 16th to the 20th century, discovering a material and cultural history that stretched from Turkey to the southern Balkans and the ports of the Italian south.

Studying traditional pottery is no mean feat. Bibliography is scant to non-existent for many areas. The respective material is not collected in museums, archives and libraries, but remains scattered. It takes knowledge, time, patience, persistence and of course money to build a pottery collection that covers a wide range of objects from different periods. Ceramics constitute the basis that enables research to progress. Their forms, decoration, colors and even their wear offer us valuable information about the societies that produced or used them.

Is there Greek ceramics tradition in Greece? How widespread is art of ceramics nowadays?

During the last two hundred years, the art of pottery continued to develop in a constantly changing socio-economic environment. The establishment of the Greek state and its gradual geographical expansion included areas known for their pottery activity. The most important ceramic centers that operated until the recent past were Patras, the Golf of Messini (Koroni), Zakynthos and Corfu in Western Greece; Arta in Epirus; Florina, Kozani and Thessaloniki in Macedonia; Metaxades, Xanthi, Komotini and Soufli in Thrace; Volos, Fanari, Tyrnavos and Agia in Thessaly; Sifnos, Andros and Kythnos in Cyclades; Skyros in Sporades; Samos, Chios and Lesvos in Northeastern Aegean; Kos, Kalymnos and Rodos in the Dodecanese; Chalkida in Evia; Crete, Aigina and of course the Attica region. At the same time, outside Greek borders, the great pottery centers of Kütahya and Canakkale remained, where hundreds of expatriate Greek and Armenian artisans were active, continuing the long tradition of the famous potters of Iznik.

The decline of the art of pottery begins in the post-war decades of the 1950s and 1960s, when new mass-produced materials appear in household appliances, such as aluminum, glass, stainless steel, and light and cheap plastic. Today in Greece there are still small “islands” that could be considered a continuation of the great pottery tradition. A case in point is the island of Sifnos where dozens of workshops are active and continue to manufacture old forms alongside modern production. Other examples include a workshop in Agios Stefanos Mandamados, Lesvos, which still fires its ceramics in a wood-fired kiln, and the jar makers of Thrapsanos in Heraklion, Crete, who continue a centuries-old tradition. Yet, the materials, the colors, the glaze are now bought ready-made from the market. Wood-fired kilns gave way to electric ones and potter’s kick wheels became electric. The old techniques and secret recipes for making colors and glazing have been lost forever.

In the last decades, the art changed orientation towards decorative, touristic, as well as artistic ceramics, satisfying the modern demands of interior decoration and souvenir shopping. But there are also many new and older Greek ceramists whose works often combine artistry with usability. Pottery has also become appealing in fine dining restaurants, which replace the classic white plates with handmade ceramics that, thanks to their uniqueness, can highlight the special identity of each kitchen.At the same time, there is an increase in pottery as a hobby. Finally, there is an increased interest in ceramics, either as collectibles or as cultural objects, fueled by books, talks, videos, exhibitions, websites and Facebook pottery groups, which brings more people into contact with modern pottery.

You are a founding member of DIKTIO, a Southeast European ceramics research group. Could you tell us a few things about the scope and initiatives undertaken by the group?

DIKTIO is an online platform, which was founded on July 15, 2016, for the study of pottery in South-EasternEurope. Focusing on Greece, we are particularly interested in Balkan ceramics, as well as Ottoman ceramics from the 15th century to the present. The aim of the Diktio is to integrate pottery into an interdisciplinary field of study. To highlight its historical and social role. To renew the approach to modern ceramics and the vocabulary we use for it. To review and re-evaluate previous relevant research. The Diktio is driven a collective spirit and thus seeks to collaborate with individuals and institutions both in Greece and abroad, to organize field research, events and exhibitions, to make publications and presentations of primary material and research. To create an archival database and build a more interdisciplinary bibliography.

The Diktio’s members have already participated in international conferences, lectures and articles in scientific journals. In addition, they compiled three editions related to traditional pottery: “ICARO-ΙΚΑΡΟΣ, the pottery factory of Rhodes 1928-1988” (2017), “Souvenir of Kütahya – Imprints of History on Kütahya’s Pottery (late 19th – early 20th century)” (2021) and “Ceramics of Chios, 17th-19th century – Angelos Vlastaris collection” (2021). The first two were accompanied by corresponding exhibitions at the Benaki Museum, while a large exhibition is planned for the ceramics of Chios at the Byzantine Museum. To support its actions, the Diktio has a collection of several thousand ceramics from Greece, Turkey, the Balkans and Italy, which is constantly being enriched.Texts and videos of the Diktio can be seen on its Facebook page: Diktio, a platform for the study of pottery in South-Eastern Europe | Facebook.

Could ceramics be used as a way to narrate the historical course of a society through centuries? What do they have to say about Greek history and culture?

Ceramics belong to one of the oldest categories of evidence related to human history. They are connected to daily life in the past and present and thus can “talk” to us about the reality of various social groups. A key advantage is their authenticity, the direct connection to the very reality to which they belong. In other words, they are not simply a testimony to the past, but are themselves an integral part of the past. At the same time, they bear evidence to the value systems, the culture, the aesthetics, the habits, the prejudices of the wider social, cultural and political environment in which they are integrated and operate.

Many ceramics bear inscriptions, dates, decoration and in general some traits that distinguish them from the rest. The members of the Diktio have focused their interest on such objects because of their direct relation to specific historical, social and cultural backgrounds. As an example, I refer to three published works by members of the Diktioin this research field. The first was compiled by Nikos Liaros under the title “The Materiality of Nation and Gender: English Commemorative Dinnerware for the Greek market in the second half of the 19th century”. The study presents commemorative dinnerware of the second half of the 19th century, which were produced in England, exclusively for the Greek market, and which depict themes relating to the Greek royal family and Greek history. According to Liaros, this national commemorative dinnerware became very popular among the middle and upper urban classes, throughout the Greek territory as well as in the diaspora. The reason for their spread is related to the historical conditions of the time, mainly to the Europeanization of Greek society, the change in the social position of women, the prevalence of national ideology and the “Great Idea”. This dinnerware helps us better understand 19th century society, illuminating areas that historical written sources do not often refer to, such as the world of the home and women.

The second paper is by Vangelis Vlachos with the title “Rooster & hen, the nuptial ceramics of Prespa before and after 1913”. The study, as Vlachos writes, focuses on two types of closed vessels for wine and raki which were widely used in weddings and festivities of the Christian Slavic-speaking population of the Macedonian countryside at least until the mid of the 20th century. The aim of this study was to put forward some initial assessments regarding their production centers, as well as the ethnic-linguistic identity of the people who made and used them. This was done mainly considering the political and social processes which were brought into play in the region during the period before and after the demarcation of its border in 1913.

The third paper is mine, titled “From Greek to Cyrillic. Inscribed pottery as evidence of cultural and national identities in the Struga region during the 19th century”. This paper refers to a particular category of ceramics produced by local potters during the 19th century in the town of Struga (North Macedonia) and its wider region. Although this pottery was made in a region of rich linguistic stratification, particularly in Struga where Slavic was the mother tongue of the majority of the inhabitants, an interesting feature in many of these ceramics is the Greek inscriptions that were gradually replaced by Cyrillic from the early 1870s. The purpose of this paper is to place this particular pottery within the historical and social context of its era, examining the influence of the Greek language in the Balkans, alongside the impact of the formation of modern ethnic states and the rise of nationalism in the Balkans from the mid-19th century onwards.

From the above examples, it becomes evident that ceramics can also be used as a way of narrating the historical course and culture of Greek society.

Could art be an effective means for fostering understanding between two cultures and nations?

Works of art exhibit the lived experience of culture and it is important for the citizen to understand the value and importance of cultural heritage and the work of art as a global good.

Focusing on traditional modern ceramics, I reckon that they can serve as yet another tool for understanding the culture and civilization of the “other”. Ottoman and European ceramics were imported in large numbers to the Greek territory, mainly from the 17th to the beginning of the 20th century. They were quickly integrated into the household as usable objects, but while they were also used as decorative objects; in this way, they became part of the historical, social and cultural context of local societies.

In the Hellenic Parliament building there are rooms with wall tiles decorated with Iznik pottery motifs, made in 1934 at the KIOUTACHIA SA factory in Moschato by Greek and Armenian refugee craftsmen. At the Pera Museum in Istanbul, a quartet of plates with the legend of Genevieve, from the workshop of the famous craftsman Minas Avramidis in Kütahya, are on display. In Struga, North Macedonia, we find ceramics with Greek inscriptions made in the middle of the 19th century by Slavic-speaking craftsmen.

Through these examples we understand that ceramics, as works of art, also function as carriers of different cultural traits that coexist within a social group and are ultimately integrated into it. The aesthetics of Ottoman pottery decorate the walls of the most emblematic building of the Greek republic, a medieval legend of Europe is depicted on the plates of a Greek-Orthodox Turkish-speaking potter from Asia Minor’s Kütahya, while the Greek language is engraved on the vessels of the Slavic-speaking regions on the banks of Ohrid.Highlighting these special cultural characteristics always helps in better communication and creates bridges of cooperation and understanding between people of different cultures.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

Also read: The long history of ceramic art in Greece; Arts in Greece | Eleni Vernadaki: Modern Greece’s Priestess of Ceramic Art