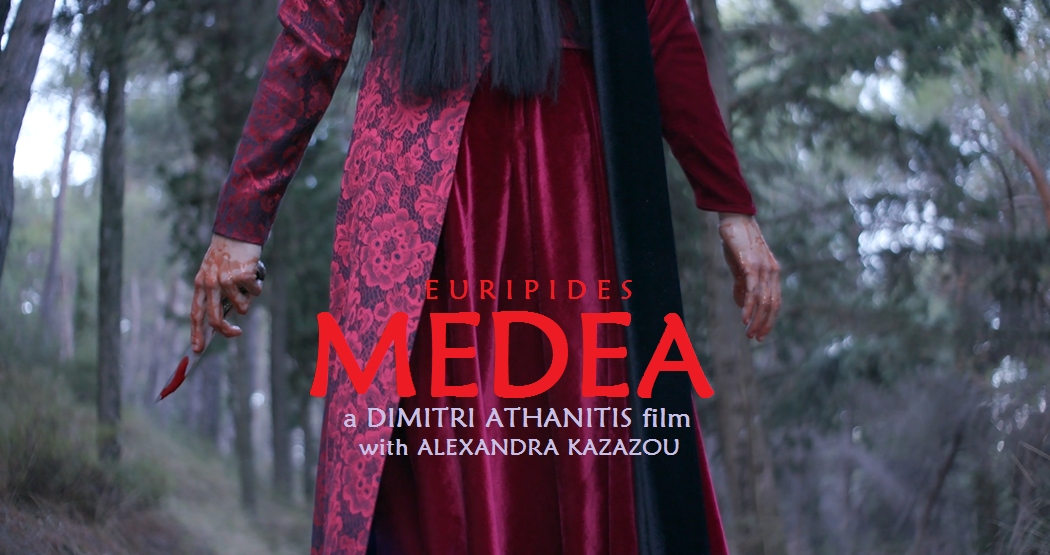

Acclaimed filmmaker Dimitris Athanitis takes on Greek tragedy in his latest film; Medea reinvents the myth and Eurypides’ famous play, with Alexandra Kazazou delivering an understated tour-de-force performance in the titular role.

Dimitris Athanitis

Born in Athens, filmmaker and writer Dimitris Athanitis studied cinema and architecture. A member of the European and Greek Film Academy, he has directed ten feature and four short films: Medea (2022), Labyrinth (documentary, 2019), Invisible (2016), Three Days Happiness (2012), Athens Underground (short, 2011), Madonna calls Fassbinder (short, 2009), Planet Athens (2005), 2000+1 Shots (2000), An Athens Summer Night’s Dream (1999), No Sympathy for the Devil (1997), Vox (television film, 1996), Addio Berlin (1994), Mister X (short,1994), and Philosophy (short, 1993).

His debut film Addio Berlin won the Jury’s Prize and Critics Mention at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival (TIFF), while his second feature No Sympathy for the Devil (1997) was nominated for Best Feature Film and won the Best Actress Award at TIFF. 2000+1 Shots was deemed one of the best films of the year by Australian film critic B. Mousoulis (Senses of Cinema film journal). Three Days Happiness won 4 awards and was screened at over 20 festivals, while Invisible won 15 awards at 40 film festivals and Labyrinth received the 2nd Award for Best Documentary at the London Greek Film Festival.

His debut film Addio Berlin won the Jury’s Prize and Critics Mention at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival (TIFF), while his second feature No Sympathy for the Devil (1997) was nominated for Best Feature Film and won the Best Actress Award at TIFF. 2000+1 Shots was deemed one of the best films of the year by Australian film critic B. Mousoulis (Senses of Cinema film journal). Three Days Happiness won 4 awards and was screened at over 20 festivals, while Invisible won 15 awards at 40 film festivals and Labyrinth received the 2nd Award for Best Documentary at the London Greek Film Festival.

He has also published three books; Secret Encounters (2017), a journey through meetings with stars, directors, writers and underground figures, Scripts (2020) whith the screenplays of his first two films, Addio Berlin and No Sympathy for the Devil, and the recently released The seventh continent / 60 films for ever (2022), in which he presents and analyses 60 films from 120 years of cinema, in a unique journey through the eyes of an auteur.

Medea

Athanitis’s latest feature, Medea, is a retelling of the eponymous ancient Greek tragedy –one of Euripides’ most famous works– based on the myth of the foreign princess who helped Jason in his quest for the Golden Fleece, followed him to Greece and had two children with him, only to be eventually spurned for a more suitable bride, leading her to an relentless act of revenge.

The film, starring Greek-Polish actress Alexandra Kazazou (in a subtle yet powerful and, at moments, harrowing performance as Medea), has already received 20 awards and distinctions in over 20 film festivals, including the awards for Best Fiction Feature Film, Best Director and Best Actress at the 15th London Greek Film Festival, Best International Feature fiction film at the 11th Athens International Digital Film Festival, Best Actress at the 11th SEE Film Festival and six nominations at the 13th Maverick Movie Awards.

Writing for KinoCulture (Montreal), acclaimed film critic Élie Castiel, who gave the film a five-star rating, described Medea as “a kind of visual and sound ecstasy, rarely felt in current cinema”, praising the “magnificent black and white images” and the masterful use of natural sounds in this “striking face to face between the Artist (Athanitis) and the Poet (Euripides)”.

Writing for KinoCulture (Montreal), acclaimed film critic Élie Castiel, who gave the film a five-star rating, described Medea as “a kind of visual and sound ecstasy, rarely felt in current cinema”, praising the “magnificent black and white images” and the masterful use of natural sounds in this “striking face to face between the Artist (Athanitis) and the Poet (Euripides)”.

Speaking about Medea, Athanitis himself has defined his film as “an attempt to re-invent the original play using primary, archetypal elements, as Medea herself is an archetype […] a mother, a stranger, a completely fallen and abandoned woman with no place to live. Medea’s character concerns us, as she is emphatically modern.” In his interview with Greek News Agenda* the filmmaker expanded on his approach to this classic work and spoke about what the powerful leading character symbolises to him.

So far, you had mainly directed films from your original scripts, starring modern-day characters. How does the adaptation of a famous ancient tragedy fit into your filmography? What led you to this choice?

So far, you had mainly directed films from your original scripts, starring modern-day characters. How does the adaptation of a famous ancient tragedy fit into your filmography? What led you to this choice?

The project of Medea came upon me, in all its detail, some twenty years ago. Five years ago I decided to make it a reality. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, although a modern adaptation of a classic, was already a precursor, and even more so my film No Sympathy for the Devil, which takes the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice to a dystopian capital. And finally Medea is in line with my earlier films like Three Days Happiness or The Devil, all of them being centred around strong female leads.

Another difference is that you leave behind the urban landscape which you have so deeply studied, with striking shots of the country’s natural landscape dominating your film. Did you feel insecure about how you would handle the natural environment in the film?

Indeed Athens has been a key protagonist in eight of my films but with my previous film Invisible I was already leaving the city. I was only on the industrial outskirts next to it, yet the natural landscape and the open horizon were strongly introduced.

As I said, Medea came to meet me herself. It was all there in my mind and it was set in landscapes just like these. And no, it wasn’t actually anything new to me, since in many of my films, the heroes turn to the sky at the end, even if they’re within the narrow city skyline.

Which were the filming locations, and what were your criteria in choosing them?

Which were the filming locations, and what were your criteria in choosing them?

I needed powerful, archetypal settings like Medea herself. The film was shot in mountainous areas in Epirus, Boeotia and Attica. The images in my mind led me to the specific choices. Of course they were not easy to find and we worked for about five years on the locations and costumes.

Were you afraid of going up against the numerous theatre directors who have staged the tragedy in the past, as well as Pasolini’s cinematic Medea?

I had every aspect of the film clear in my mind and I was not concerned about any comparison or reference. After all, it is completely original. As for the Callas film, as a work it does not go beyond a superficial iconography.

A few months ago, a woman in Greece was accused of murdering her three children driven by the fear of being abandoned by her husband. Do you approach Medea as an actual disturbed woman or as a symbol that transcends the dramas of everyday life?

A few months ago, a woman in Greece was accused of murdering her three children driven by the fear of being abandoned by her husband. Do you approach Medea as an actual disturbed woman or as a symbol that transcends the dramas of everyday life?

Medea is the most powerful female character that has ever existed. She is a unique woman who does not hesitate to resist in order to survive. Killing her children is the last thing she does. She is an incredible example of freedom and self-belief and obviously a symbol.

Do you think that Medea also symbolises the desperation of refugees and those facing xenophobia? Did you therefore choose a leading actress of mixed heritage?

My Medea is completely faithful to Euripides’ masterpiece but at the same time, it reinvents it. And indeed, at the beginning of the film, as in the original tragedy, Medea with Jason and their two children are refugees in Corinth. I chose an actress I had hardly ever seen perform, and her dual heritage confirmed to me the power she hid within.

The main difference between your film and Euripides’ tragedy comes at the ending, and concerns whether the protagonist shows any signs of remorse (not only for the infanticide but also for the murder of her rival, Glauce); we don’t see the flying chariot of the sun god Helios, but catharsis seems to be brought by the sun. Did you want to distance yourself from the unrelenting and superhuman Medea as depicted in the tragedy (and in mythology)?

The main difference between your film and Euripides’ tragedy comes at the ending, and concerns whether the protagonist shows any signs of remorse (not only for the infanticide but also for the murder of her rival, Glauce); we don’t see the flying chariot of the sun god Helios, but catharsis seems to be brought by the sun. Did you want to distance yourself from the unrelenting and superhuman Medea as depicted in the tragedy (and in mythology)?

As I said before, the film reinvents the original play while keeping true to the spirit and largely to the letter of the tragedy. I have rearranged the characters, added silent scenes, brought the word into the present day. And of course, unlike tragedy, in the film no one knows what will happen right after the end. Not even Medea herself.

I identify with Medea, I identify with this strong woman, this daughter of a king, who has now lost everything but doesn’t give up. And in the end, what I strive for in every film I make is exaltation.

What are your current projects or plans?

What are your current projects or plans?

I just released my new book The seventh continent / 60 films for ever, where I choose 60 films from 120 years of cinema based on genuineness; an anthology that subverts the clichés that have been dominant for decades and indirectly rewrites cinema history through the selections and commentaries and through what is left out. An original book that is unlike similar collections and, at the same time, I can say that it reads like a charming novel.

I have also just started auditions for an upcoming film that definitely has some connection to Medea, while I am also working on another docu-fiction in the style of Labyrinth.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi

Photos by Toula Akrivou; Portrait of Dimitris Athanitis by Vaggelis Douros

Read also via Filming Greece: Labyrinth: Dimitris Athanitis and the Uncanny Elegance of the Arcades; Dimitris Athanitis on scratching beneath the surface of the Invisible; Yorgos Goussis explores the power of togetherness in Magnetic Fields