Takis Kayalis is Professor of Modern Greek Literature at the Hellenic Open University. He studied English and Greek Literature at the University of Athens, the University of Essex, and New York University, from which he received his Ph.D. in English Literature supported by Fulbright and Woodrow Wilson Fellowships. He has previously taught Modern Greek and Comparative Literature at Queens College, CUNY; the University of Crete; the University of Cyprus; and the University of Ioannina. He designed and implemented a large number of research projects at the Center for the Greek Language in Thessaloniki, where he served as member of the Executive Board and Academic Director of the Language and Literature Department from 1994 until 2011. He co-edited the Digital Collection of the Cavafy Archive (Onassis Foundation, 2019) and since 2017 he serves as a member in the Archive’s International Academic Committee. His research focuses on 19th- and 20th-century literature and criticism, digital humanities and literary pedagogy.

Ηis books in English include: Cavafy as World Literature (co-editor with Vicente Fernández González, Bloomsbury Academic, forthcoming in 2025); Cavafy’s Hellenistic Antiquities: History, Archaeology, Empire (Palgrave Macmillan, 2024); Teaching Literature at a Distance: Open, Online and Blended Learning (co-editor with Anastasia Natsina, Bloomsbury Academic, 2010). His books in Greek are: Ο Καβάφης στην εποχή του (επιμ.) [Cavafy in his Time, ed.] (opportuna, forthcoming in 2024); Η ποιητική θεωρία του Γ. Σεφέρη και η κριτική: Όψεις της κατασκευής του ελληνικού μοντερνισμού [George Seferis’ Poetic Theory and its Critical Reception: Aspects of the Construction of Greek Modernism] (Kallipos Open Academic Editions, 2023); Ο Σεφέρης για νέους αναγνώστες (επιμ. με τον Ε. Γαραντούδη) [Seferis for Younger and New Readers, co-ed. with E. Garantoudis] (Ikaros, 2008); Η επιθυμία για το μοντέρνο. Δεσμεύσεις και αξιώσεις της λογοτεχνικής διανόησης στην Ελλάδα του 1930 [The Desire for the Modern. Limitations and Claims of the Literary Intelligentsia in Greece During the 1930s] (Bibliorama, 2007); Γλουμυμάουθ: Ο βικτωριανός Α. Ρ. Ραγκαβής [Gloomymouth: The Victorian A. R. Rangabé] (Nefeli, 1991).

Your latest writing venture Cavafy’s Hellenistic Antiquities: History, Archaeology, Empire (Palgrave Macmillan, 2024) reinterprets C. P. Cavafy’s historical and archaeological poetics by correlating his work to major cultural, political and sexualized receptions of antiquity that marked the turn of the 20th century. Tell us a few things about the book.

To begin with, I must confess that this book took me almost a decade to research and write. Its span is quite broad, so it is not easy to sum it up in a few words. The book’s main objective is to provide a radically new reading of Cavafy’s historicism by situating his poetry in the context of a broad spectrum of intellectual and cultural pursuits of his time. These include the cultural tradition of antiquarianism but also diverse appropriations of the classics that operated at the turn of the 20th century, particularly those that sought to legitimate homoerotic desire and to promote British colonial rule.

Could you present us your book’s main topics?

Let me try to lay out some of my main premises, focusing on a few of the book’s key concepts and themes.

- Antiquarianism

History, as Cavafy learned it by his moderate education and through his avid readings, was still very much a field of antiquarian discourses and pursuits. His intellectual and cultural interests as a young man reveal the sensibility of a latent antiquary, an amateur historian in the long tradition of laymen who acted as readers, explainers and collectors of the past, addressed antiquity through contemplation and nostalgia and identified with it by projecting their own interests on it. Cavafy embraced antiquarianism as an accessible, empathetic and passionate way of relating to the past and creatively transformed it, in his poetry, into a method for discovering and revealing homoerotic meanings as well as various other distinctly modern conflicts and situations in Hellenistic and late ancient antiquities.

- Desire

My book seeks to contextualize Cavafy’s historicized representations of homoerotic desire by correlating them to a broad set of intellectual, artistic and ideological figurations that were active in the early twentieth century. These range from manifestations of the alarming triadic scheme of “luxury, indolence, and effeminacy” to the joint venture of deferring homoerotic desire to martial, chivalric and middle-class norms in an effort to legitimize it. Certain aspects of Cavafy’s erotic poetry may also be fruitfully compared with photographer Wilhelm von Gloeden’s visual project. Both artists explored representations of manly love by staging them in similar pseudo-historical settings. Like Cavafy’s, von Gloeden’s erotic archaeology focuses on post-classical and Decadent versions of antiquity, while his photographs clearly suggest Hellenistic and Late Antique hybridity. In fact, both artists appear to have used antiquarianism as a code by which they could either cloak or reveal homoerotic desire, depending on the reader who confronted their work.

- British Imperial Culture

In contrast with the poet’s earlier ethnocentric apprehension, several recent studies have established Cavafy as a poet of the Greek diaspora whose upbringing, culture and manners were distinctly British; Cavafy is now often perceived as “a British national with a Greek passport,” who lived in colonial Egypt and worked as a clerk in a British-run colonial office. My book’s approach, however, is not biographical. In researching Cavafy’s imperial contexts, I am more interested in his proximity to colonial cultural capital, which included scholarly works, Victorian British periodicals and other similar material, but also featured a network of classically-educated and highly-cultured British friends and acquaintances, who read and promoted his work and also brought to his attention scholarly material, including new ideas and fresh perspectives on antiquity. Apart from E. M. Forster, Cavafy’s so far under-researched colonial network featured several important scholars and politicians like T. E. Lawrence, Ronald Storrs, Edgar John Forsdyke, Robin Allason Furness and George Antonius.

I also often seek connections between Cavafy’s perceptions of Eastern Hellenism and its articulations in scholarly and cultural texts, which filtered and shaped the poet’s understanding. The complex and dazzling transport of perspectives that emerges as we observe Cavafy studying Hellenistic history from British imperialist scholars, who were at the same time studied, praised and used by eminent imperial figures like Lord Cromer, is a major theme under investigation in my book. Cavafy thus emerges as a poet who read and wrote of Eastern Hellenism through facilities, resources, and viewpoints made available by the British Empire, while also keeping his distinct cultural identity and seeking to increase his cultural capital as a diaspora Greek within the broader colonial framework in which he lived and operated.

Ιn what ways, has Cavafy’s poetry rendered modern meanings to Hellenistic antiquities?

Cavafy’s creative use of episodes from Hellenistic history and items of archaeological interest, such as inscriptions, coins and other objects of material antiquity, continues to fascinate and perplex his large international audience. However, criticism has often viewed the poet’s historicism in impressionistic terms: either as a simple disguise of his private yearnings or as a more or less conventional expression of universal axioms and truisms. My book seeks to transcend these rather superficial interpretations of Cavafy’s uses of the past by focusing on poems which stage readings of Hellenistic and late ancient antiquities, such as coins, epigraphs and craters, and reexamining in great detail the poet’s handling of them. Drawing on material from the recently digitized Cavafy Archive of the Onassis Foundation, as well as from books in the poet’s personal library, I trace the poet’s specific historical and scholarly sources and explore the complex ways in which he made creative use of them. By locating Cavafy’s actual sources and by carefully reviewing his creative handling of them, I probe into his creative process in precise, specific and tangible terms. This leads to a new understanding of the poet’s favored antiquarian persona, the voice which speaks in many of his historical poems, and of its complex function. As I argue, this narrative device plays a crucial role in Cavafy’s poetics, as it enabled him to present queer readings of ancient texts and artifacts as ruminations that are seemingly articulated by a voice of cultural authority and engulfed in mainstream antiquarian practice.

As my book demonstrates, Cavafy appropriated the common perception of old-time antiquarians as passionate readers, appraisers and collectors of antiquities. But his quasi-antiquarian interpretations of ancient texts and material objects were also infused with a heavy dosage of Walter Pater’s aestheticism and capable of expressing homoerotic desire in a voice authorized by its scholarly reverberations. And so, by appropriating antiquarianism as his creative persona, Cavafy was able to reorient it towards the fictional discovery of ancient queer legacies, in which he traced alternative ways of feeling, of thinking, of living and even of reading ancient literature and art.

How is Cavafy’s historicism related to the discourses and intellectual pursuits of his time?

This is indeed the major aim of my book: to situate Cavafy’s historical poetry, in the context of a broad spectrum of intellectual and cultural manifestations of his time. Or, to put it differently, to historicize Cavafy’s own poetic historicism, by discerning the contemporaneous conceptual and aesthetic premises that shaped it and made it so distinctly modern. I like to think that I have pursued this objective systematically and at a variety of different levels. Let me try to illustrate my approach with two examples.

Focusing on Cavafy’s aesthetic uses of ancient coins, like Orophernes’s tetradrachm, I survey late 19th-century antiquarian and physiognomic interpretations of coin portraits together with insights from the domain of photography, which was very influential in Cavafy’s formative years. I also discuss the ways in which ancient coin portraits were approached and conceptualized in the poet’s time by early professional numismatists, who were mostly based at the British Museum. Then, I correlate these formulations with the perception of ancient coins in late 19th-century literary texts by Walter Pater, Thomas Hardy, Charles Tennyson Turner, Oliver Gogarty, Vernon Lee, José-Maria de Heredia and other authors. This presentation lays out a network of conceptual frameworks which operated in Cavafy’s time and allow us to contextualize his rendering of ancient coin portraits and to trace the residue of antiquarian, physiognomic, aestheticist and other cultural perceptions that shaped his aesthetic outlook.

Turning to a different example, we may consider Cavafy’s famous poem “Caesarion,” which has been repeatedly and rather frivolously read as an autobiographical episode, in which the poet confessed the “method” by which he supposedly composed his historical poetry. In this case, I trace Cavafy’s source in J. P. Mahaffy’s Empire of the Ptolemies (1895), a book mentioned by Stratis Tsirkas, which the poet employed as a storehouse of narrative patterns, tropes and motifs.

Then I present new research findings that effectively cancel the central premise by which critics have read “Caesarion” in the last century or so: the belief that Cleopatra’s son was a marginal or obsolete historical figure until Cavafy’s poem drew attention to him. As I demonstrate, Caesarion was a familiar and highly recognizable historical figure long before Cavafy’s famous composition. In fact, I managed to locate several earlier literary manifestations of Caesarion in texts by a range of European authors, from the well-known Victorian poet Walter Savage Landor to Léon Michaud d’Humiac, an elusive French dramatist who lived in Egypt and died there just before his last play, Caesarion, was printed in Paris. That was in 1913, a year before Cavafy composed the first draft of his poem.

As I demonstrate, throughout his many literary transformations before entering Cavafy’s poetry, Caesarion was never connected to conventional masculine stereotypes. On the contrary, a significant feature of this figure’s composite portrait consists of insinuations or direct attributions of effeminacy, which may explain why he is the only ancient historical figure to be openly celebrated as an object of same-sex desire in Cavafy’s poetry. But the context of Cavafy’s poem is actually even richer, as Caesarion’s famous vanishing from the domain of public history may be related to his absence from early 20th-century cinematic renderings of the story of Antony and Cleopatra. These include the Italian silent film “Marcantonio e Cleopatra,” directed by Enrico Guazzoni and starring Gianna Terribili-Gonzales, that was shown for a record period of ten weeks at the Greek moviehouse Iris, in Alexandria, shortly before Cavafy wrote the first version of his “Caesarion”.

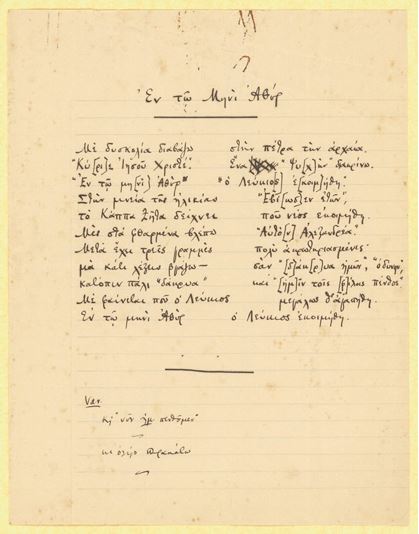

Manuscript of “In the month of Athyr” © 2016–2018 Cavafy Archive, Onassis Foundation

Cavafy has been one of the most researched Greek poets. What is it that makes his work both timely and timeless?

As I am sure you are aware, this is a puzzle that critics have tried to solve at least since 1946, when George Seferis crafted Cavafy as a modernist, teaming him with T. S. Eliot and implicitly with himself. A body of work that is perceived as timeless and timely at once is what we usually define as a modern classic. Cavafy’s poetry, with its amazing appeal throughout the world and to readers from different age groups and cultural backgrounds, has surely attained this status. Without pretending to possess a single or definitive answer to the mystery of Cavafy’s ever-growing appeal, I can try to outline a few pathways around it. A feature of Cavafy’s poetics that I think many contemporary readers find compelling, and which allows them to identify so intimately with his voice, is his sense of irony: Cavafy’s distanced, gracious and often stoic take on the human condition and more specifically on the discrepancies between an individual’s apparent prospects, his or her self-deceptive figurations and their actual fate. This is a pattern that our poet obviously enjoyed exploring, as it underlies many of his poems.

This ironic quality is akin to Cavafy’s positioning as a reader of texts who deciphers obscure meanings and ruminates on them, in a way that allows for indeterminacy, speculation and even error, rather than as a seer or a singer of eternal truths. As you know, Cavafy is not at all about the glee of raw talent and self-adoration. He is actually more about failure, consolation and endurance. And of course, we must also take into account his unparalleled way of manifesting and celebrating homoerotic desire in a shadowy room of the early 20th century. Cavafy’s audacity to express homosexuality in an idiom of love, compassion, fantasy and reminiscence is a quality that makes his poetry not only timeless and timely, but also unique and precious to so many readers in this day and age.

*Ιnterview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE