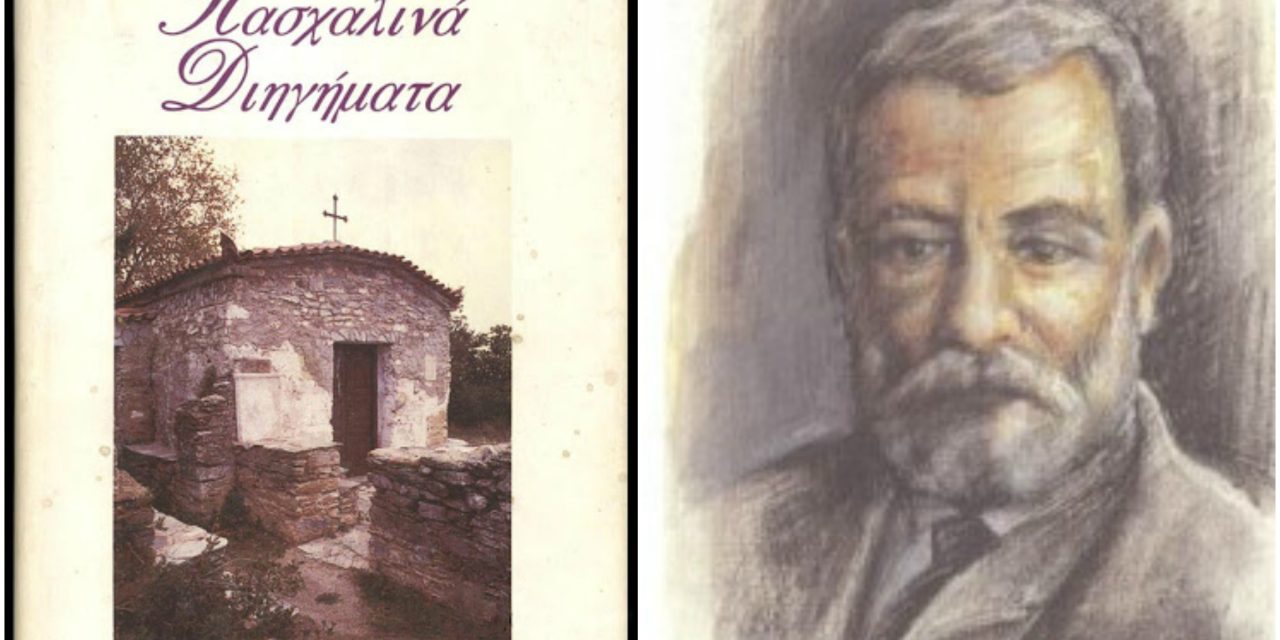

What a better way to feel the true spirit of the Greek Orthodox Easter than by reading the Easter short stories of ‘the saint of modern Greek storytelling’ Alexandros Papadiamantis.

In A Village Easter, the priest, Father Kyriakos, is beset by financial worries and literally runs out of the country chapel mid-liturgy to confront his fellow priest at the church in town because he believes that his fellow priest is taking more than his fair share of the offering. Besides the specific problem of a congregation suddenly bereft of a priest and the Easter liturgy, the story also underlines the problem of clergy not being adequately paid for their work.

In The Easter Chanter, the chanter who has promised to come finally arrives near the end of the service. His tardiness is largely his own fault because he did not leave home when he should have. The priest is frustrated and tempted to cancel the liturgy altogether, and in the end has to improvise with his illiterate and unchurched parishioners. The story then ends with a man sneaking meat from the lamb while it is roasting, and being slyly punished in retaliation by the man in charge of the roast who should have been paying more attention.

In the most tragic story, Without a Wedding Crown, the disgraced Christina, trapped for years in a manipulative relationship with a man who repeatedly promises marriage and never follows through, longs to attend the Holy Week and Paschal services but is too ashamed to show her face to the other, more respectable women. Instead, Christina finally leaves home to attend paschal vespers, which is a chaotic service full of servants and nannies enjoying their afternoon off. There is also an unflattering description of the churchwarden, who in trying to shush crying babies causes an even greater disturbance.

Yet despite these conflicts and anxieties, the joy of the resurrection does poke through. Father Kyriakos comes to his senses and returns to the chapel to finish celebrating the liturgy. He is also later reconciled with his fellow priest, and realizes that his fears about the offering was just a misunderstanding. The tardy chanter finally take his place in the chapel and helps the priest and the congregation finish the liturgy. The man punished for sneaking meat still receives a few bites of the festal meal, saved for him by a couple of the older women. Christina is perhaps the only person attending paschal vespers who understands the significance of the feast, despite her shame and oppression.

In his introduction to The Boundless Garden: Selected Short Stories, Volume I, Lambros Kamperidis notes that “through his lively, tender, and profound short stories of the simple lives of the Orthodox faithful of his native island of Skiathos, Papadiamantis reveals a world of organically lived Orthodoxy, largely lost in the disintegrating order of modern life”. Through his narration, Papadiamantis makes an effort to express his harsh criticism against those who despised Orthodoxy and religious stories, and those who tried to imitate western manners. In his view, these people were alienated from the essence of the nation, namely its customs and religion. A Greek does not have the right to be an atheist or a cosmopolitan, since he “then would resemble a dwarf who stands on his toes in order to look as tall as a giant”.

Papadiamantis describes the Holy Week most eloquently in so many of his short stories and articles: “… the incense drifts in blue fragrant wreaths and forms a fleeting surround for the girls, in their embroidered aprons and white sleeveless jackets, come bearing armfuls of roses and violets and sheaves of rosemary and proceed to heap mountains of flowers on the humble Epitaphios, which needs no further embellishment”. He goes on to note that “the Greek nation’s Easter (Pascha in Greek) rises and sets with the noisy dispersion and supreme exultation of the people, who still have drops of blood running in their veins from their wild and unbridled ancestors, who are lulled by the love of freedom”.

Papadiamantis’ short stories do a masterful job of recounting the traditional Greek Orthodox ethos. In Papadiamantis’ world – a world that is lit with the light of Christ – there is room for everyone. Each one of the characters behaves and reacts in their own unique way, not trampling upon the personality of the other, irrespective of right and wrong, good and bad. Papadiamantis’ deep Christian faith, complete with the mystical feeling associated with the Orthodox Christian liturgy, suffuses many stories. Most of his work is tinged with melancholy, and resonates with empathy with people’s suffering, regardless of whether they are saints or sinners, innocent or conflicted.

The author

Revered as “the Dostoyevsky of Greece”, Alexandros Papadiamantis was born on 4 March 1851 on the small island of Skiathos. His first novel, The Migrant, was printed in instalments in the Constantinopolitan newspaper Neologos, in 1879, and a further three novels were similarly published in Athens in the following years. It was also during this period that he started working as a translator for various Athenian newspapers.

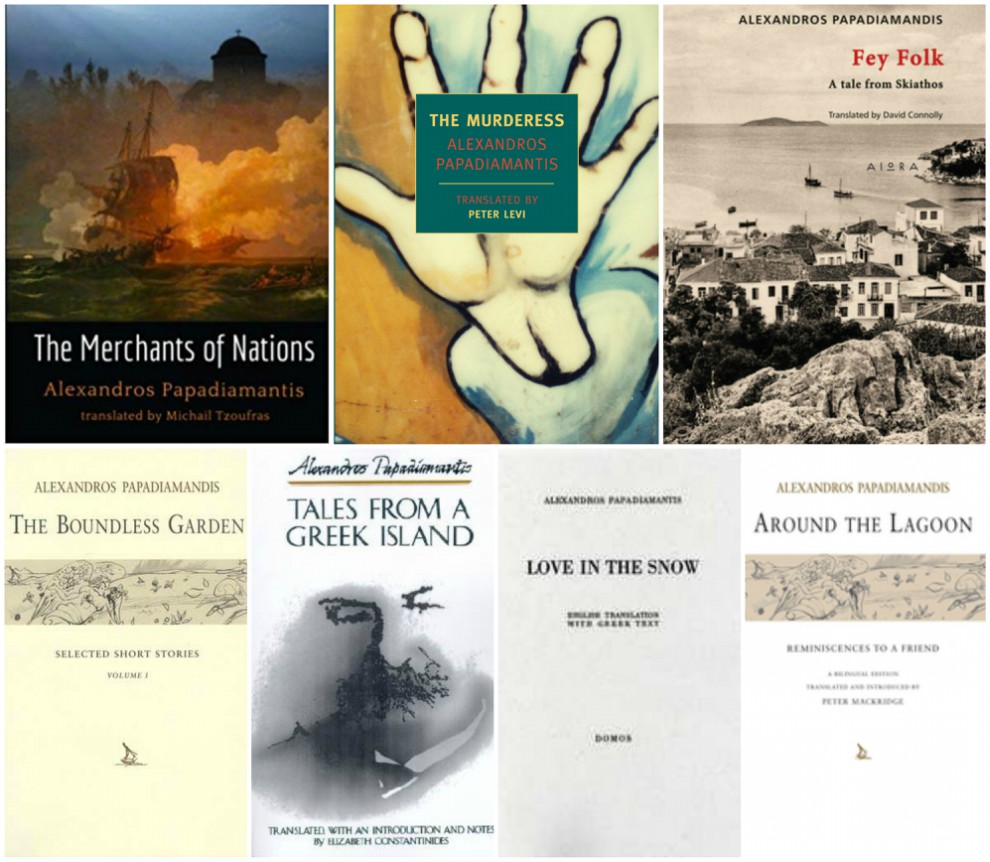

It wasn’t, however, until Christmas of 1887 that Papadiamandis’s first short story, The Christmas Loaf, was to appear, marking the feast and setting a pattern for his writing. The metier of the short story subsequently became his favoured form, written in his own version of the then official language of Greece “katharevousa”. Except for two years when he returned to Skiathos, 1902–4, during which time he wrote his perhaps most powerful tale, The Murderess, he continued to live in Athens, writing and translating, until 1908. His longest works were the serialized novels The Gypsy Girl, The Migrant, and The Merchants of Nations. These were adventures set around the Mediterranean, with rich plots involving captivity, war, pirates, the plague, etc.

His work is considered seminal in Modern Greek literature: he is for Greek prose what Dionysios Solomos is for poetry. As Odysseus Elytis wrote, “commemorate Dionysios Solomos, commemorate Alexandros Papadiamantis“. It is a body of work, however, that is virtually impossible to translate, due to the magic mixture of his language: elaborately crafted, high “katharevousa” for the narrative, interspersed with authentic local dialect for the dialogue, and with all dialectical elements used in the narrative formulated in strict “katharevousa”, and therefore in forms that had never actually existed.

It is fair to say that the growing contemporary preoccupation with and re-evaluation of the work of Papadiamandis convey a measure of its relevance for our times. More than a century after his death, his imaginative insight of the Greek way of life, his uncompromising attitude with regard to the dilemmas plaguing the newly-created nation on the threshold of modernity, his caustic humour directed against those who vitiated the traditional ways, and his unyielding defense of ancestral values and revealed truths would seem to have been sufficient reason a generation ago to relegate him to oblivion. The enduring relevance of his work today is a living proof of the persistent significance of its message.

A.R.