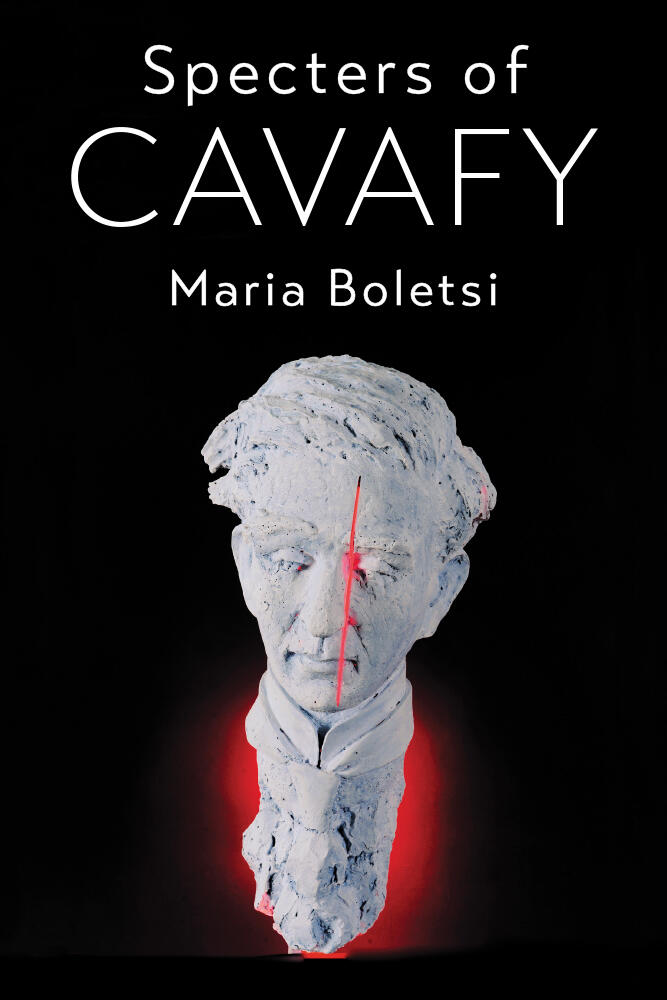

The Greek Alexandrian poet C. P. Cavafy (1863–1933) has been recognized as a central figure in European modernism and world literature. His poetry explored the conditions for animating the past and making lost worlds or people haunt the present. Yet he also described himself as “a poet of the future generations.” Indeed, his writings address concerns and desires that permeate the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Specters of Cavafy by Maria Boletsi (University of Michigan Press, 2024) broaches these questions by proposing spectral poetics as a novel approach to Cavafy’s work. Drawing from theorizations of specters and haunting, it develops spectrality as a lens for revisiting Cavafy’s poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction, as well as his poetry’s bearing on our present.

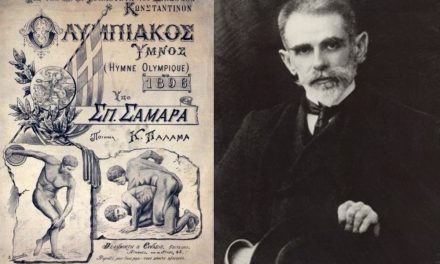

Book cover of Specters of Cavafy, featuring the artwork “Cavafy” (bust) by Apostolos Fanakidis. Polyester and neon, 2013. Photograph by Thaleia Kimbari

Reading Greece spoke to Maria Boletsi* about the book, the notion of ‘spectrality’ as a conceptual metaphor for revisiting Cavafy’s idiosyncratic modernist poetics, as well as about what makes his work both timely and timeless.

Your latest writing venture Specters of Cavafy (University of Michigan Press, 2024) proposes spectrality as a conceptual metaphor for revisiting Cavafy’s idiosyncratic modernist poetics and as an analytical lens for probing his poetry’s afterlives in contemporary settings. Tell us a few things about the book.

Since I got hooked on his poems as a teenager, Cavafy’s writings have become my partners in thinking, guiding the ways I make sense of other texts, cultural objects, and situations in my own life and in our sociopolitical realities. His “Waiting for the Barbarians,” for example, was the trigger and, in some ways, the backbone, of my doctoral research and my book on the modern and contemporary travels of the concept of barbarism in literature, philosophy, and art (Barbarism and Its Discontents, 2013). The fact that Cavafy’s writings have been taken up, adopted, translated, cited, and used in such diverse ways points to the countless twists and turns that his address to future readers has taken, globally. Having just convened the Cavafy Summer School of the Onassis Foundation on “Theater and Performativity” in Cavafy together with Gonda Van Steen, I was once more pleasantly struck by the refreshing, new questions young scholars from the Global North and South pose to Cavafy’s work, which keep renewing the terms of Cavafy’s conversation with our present. Specters of Cavafy is my own attempt to make sense of Cavafy’s mode of haunting, on a personal and collective level.

The book tries to reckon with a seeming paradox. On the one hand, Cavafy’s writing is obsessed with the past. He persistently experimented with strategies for conjuring the past in the present and making people or experiences from the past—including the poems themselves—unpredictable forces in future presents. On the other hand, his writing seems to address the future and to anticipate future societies and communities of readers. Cavafy, too, saw himself as “an ultra-modern poet, a poet of the future generations,” as he wrote in an unpublished self-appraisal in 1930 (in French; trans. Peter Jeffreys). This apparent paradox shaped the book’s central questions:

What are the conditions that make the dead haunt in Cavafy’s writings? How does a poetry that concerns itself with the past, memory, loss, and death, carry futurity? How does it haunt future presents?

Cavafy’s double preoccupation with the past and the future is at the heart of what I call spectral poetics. This poetics comprises strategies of temporarily animating the past, keeping death and finality at bay, and opening up the future, without appealing to eternal life, fixity or permanent truths. In Cavafy’s universe, no truth is eternal, no perspective is uncontested, no presence is permanent, and no identity is stable. When scenes or people from the past are summoned – like prince Caesarion in the homonymous poem or the speaker’s past lovers and dead family members in “Since Nine—” (“Απ’ τες εννιά—”) – they remain transient presences that never fullyhypostatize. Conjurations of the past are precarious and invested with an intensity that stems from the threat of their imminent disappearance. This precariousness, I claim in the book, is inherently linked with the ability of Cavafy’s writing to haunt different futures. I explain why in my answer to your last question.

In the book, I take my cue from Jacques Derrida’s Specters of Marx (Spectres de Marx, 1993) – to which my book’s title alludes – to propose the specter as a conceptual metaphor for revisiting Cavafy’s modernist poetics and his poetry’ afterlives today. Simply put, I am concerned with the ways Cavafy’s writing haunts, and is haunted by, the past as well as by future presents, up to the contemporary moment. This double inquiry roughly corresponds with the book’s two parts. In the first part, I revisit Cavafy’s poetics through the lens of spectrality. Here, I trace techniques through which poetic subjects try to activate the past (not always successfully, as I explain in my answer to your second question). These techniques include broken promises and conjurations: two speech acts that I deem central to Cavafy’s spectral poetics. To draw the contours of this poetics, I close-read poems as well as prose works: fictional, such as the short story “In Broad Daylight” (“Εις το φως της ημέρας,” 1985-1986) and non-fictional, such as a text posthumously published and known as “Philosophical Scrutiny” (1903) and Cavafy’s diary from his first visit to Greece in 1901. In the second part, I turn to his poetry’s bearing on our present, in the Western cultural and political imaginary since 1989 and in contemporary crisis-ridden Greece. Here, I ask how Cavafy’s poems haunt contemporary realities, and how their recastings, adaptations, and citations can yield unexpected readings that renew the poems’ ability to haunt us unpredictably.

Kostas Bassanos, “In Search of the Exotic,” 2016. Installation view at EVA International – Ireland’s Biennial 2016. Dimensions variable. Photo Miriam O’Connor. Courtesy the Artist and EVA International

In the second part, for example, I take readers through the afterlives of “Waiting for the Barbarians” (“Περιμένοντας τους βαρβάρους”), a poem that has figured in literature, visual art, music, popular culture, and politics in so many contexts. I focus mainly on its figurations in Western political commentaries since the early 1990s, and especially since September 11, 2001, when uses of the poem in discussions about post-Cold War and post-9/11 realities up to recent debates on terrorism become remarkably frequent. The question that interests me is which conceptions of history and visions of the future the poem’s political uses promote. This question leads me to explore the poem’s critical engagement with progressive and decadent historical narratives in modern European thought, e.g., in Edward Gibbon and Ernest Renan. Through these conversations, I ponder the poem’s revolutionary gesture of breaking with historical patterns and reintroducing the future – a future without barbarians – as an open question. In my last chapter, I follow Cavafy’s specters from colonized Egypt to contemporary Greece during the country’s debt crisis, to ask how his poems haunt us today despite regulatory practices aimed at safeguarding the poet’s myth and his poetry’s meanings. Here, I propose a “fragmentary reading” of the poem “In a large Greek colony, 200 B.C.” (“Εν μεγάλη Ελληνική αποικία, 200 π.Χ.”) by revisiting it through its future fragments: the fragmented verses that circulated in Athens during a publicity campaign by the Cultural Center of the Alexander Onassis Foundation, aimed at celebrating the Foundation’s acquisition of the poet’s archive and opening it up to the public.

As this already suggests, the book crosses spatiotemporal frames and takes part in transnational conversations. For this reason, I feel fortunate that it found its ‘home’ in the new book series “Greek / Modern Intersections” at the University of Michigan Press (with Artemis Leontis as series editor) – a series that publishes scholarly work concerned with how the past is recast from the present and with placing Greek cultural production in comparative perspectives. The spirit of the series chimes with the book’s aim to bring Cavafy’s work to bear on theoretical debates in literary and cultural theory, affect and queer theory, performativity, irony, and spectrality, as well as in transnational encounters with works from literature, the arts, journalism, historiography, and political rhetoric. So the book joins studies that have situated Cavafy’s work not only in Modern Greek studies but also in world literature, modernism, postcolonial studies, poststructuralism, and queer studies. It is important to stress, though, that the book does not seek to ‘apply’ recent theoretical approaches to Cavafy’s work: his writings are metaleptically recast through discussions in these fields, just as they proleptically contribute to them, as partners in a conversation from which they all emerge changed, different.

How is the figure of the specter and the idea of haunting used as analytical tools to approach Cavafy’s work? How is spectrality as a conceptual metaphor used to elaborate on his modernist poetics?

What led me to the figure of the specter is Cavafy’s own preoccupation with spectral entities in his poetry, as well as the nonlinear, spectral temporality his writings enact. Recent theories on spectrality and haunting since the 1990s gave me the vocabulary and conceptual tools to draw the premises of Cavafy’s spectral poetics and their implications. I thus propose spectrality as a new framework for understanding Cavafy’s modernist poetics as well as a mode of reading that, I believe, does justice to the spectral temporality Cavafy’s writings stage and invite.

Let me try to unpack these claims. Cavafy’s poetic universe teems with spectral entities in the form of (literal) ghosts, shadows, apparitions, visions, epiphanies of gods, conjured lovers, historical figures, scenes, and sensations. In the poems, we find a rich vocabulary for such entities (among the words Cavafy uses are είδωλον, είδωμα, ίνδαλμα, οπτασία, όραμα, σκιά, φάντασμα, φάσμα). The book, however, is not only about ghosts as a theme in Cavafy. I discuss how Cavafy’s preoccupation with the spectral took shape in his early work through his engagement with esoterism, spiritualism, and decadence. Yet I am mainly interested in how the spectral metaphor permeates Cavafy’s modernist poetics – not only in his later, “realist” phase, but already in his early writings. In his later writings, specters become increasingly abstract and disengaged from the supernatural: they tend to appear when the poetic subject summons them in the present. Spectrality, however, remains a recurring component of his poetics throughout his work – poetry and prose, fiction and non-fiction.

To trace the spectral qualities of Cavafy’s poetics, I draw from theorizations of the specter-figure. Owing mostly to Derrida’s Specters of Marx, ghosts and specters have been circulating widely since the 1990s as conceptual metaphors in the humanities and social sciences, giving shape to what some call a “spectral turn” (Weinstock 2004). The Spectralities Reader (2013), edited by Maria del Pilar Blanco and Esther Peeren, registers the pervasiveness of specters since the 1990s as “influential conceptual metaphors” in culture and scholarship (2013). A conceptual metaphor, according to cultural theorist Mieke Bal, is a figure of thought and analytical tool that can “do” theoretical work and open up new ways of framing and understanding texts and, more generally, our realities (Bal 2010). So how can the specter work as conceptual metaphor? A specter is a liminal figure: between presence and absence, materiality and immateriality, life and death. As a conceptual metaphor, it has been used to talk about liminal states, questions of power, ‘invisible’ subjects leading spectral lives (such as undocumented migrants), conflicting epistemological positions that do no crystallize into certainties, uncertain agency, and a nonlinear, spectral temporality in which the present is unhinged by the past and the future.

The notion of spectral temporality takes us to Derrida’s Specters of Marx – written after the fall of communism, in a new political reality that some (naively) welcomed as “the end of history.” Rejecting this end-of history diagnosis, which rested on a linear, progressive understanding of history, Derrida revisited the relation between present, past, and future by proposing a practice he termed “hauntology.” In hauntological time, Derrida suggested, history does not move forward, but appears and recedes, making shifting claims on the present. The present becomes porous, unsettled by forces from the past and the future that occupy and co-shape it, carrying different lessons, warnings or hopes each time. These spectral forces may be willfully conjured or appear unexpectedly, bringing with them traces of (forgotten) voices of the dead or the not-yet-born that we have an ethical duty to listen to. For Derrida, hauntology thus involves a demand for justice, which requires that the future remain open to the Other. Specters are such figures of otherness: by transgressing temporal lines and ontological boundaries, they ensure that the present is not closed-off and the future is not predetermined by the past.

How can we bring all this back to Cavafy? The figure of the specter offers me a way to reckon with the paradox I mentioned before: a poetry that obsessively turns to the past and yet addresses the future. This, I suggest, ceases to be a paradox when we abandon a normative notion of linear time in favor of a spectral temporality in which time moves in different directions. Inviting specters from the past, allowing them to exert their (unpredictable) influence on the poetic present, sometimes creates openings for imagining alternative futures, even when these are still unimaginable in Cavafy’s present; futures, for example, in which queer subjects are not condemned to living spectral lives of social invisibility. Derrida’s thinking helped me grasp how conjurations of the past in Cavafy are linked to questions of justice and futurity.

Conjurations are a central tenet of Cavafy’s spectral poetics. Poetic language is not a means of recording memories or representing past events and characters. As I already argued in my earlier work, it is performative: a force of poiesis that tries to “present” in the sense of “making present,” to call up past scenes and experiences and bring historical or fictional characters onto the poetic stage (Boletsi 2006). Yet the performative force of poetic language is by no means omnipotent. Performativity in Cavafy is not only about bringing worlds, characters, and events into being. It is also about compromised agency, the faltering of the speaker’s control, the gaps between what characters say and mean or what they say and do, the limits of language’s power, its insubordination to the speaker’s intentions, and, ultimately, the productive force of these gaps, breaches, and failures. These breaches are symptomatic of the instability of seemingly homogeneous contexts, the transgressive force of homoerotic desire, and the porousness of social codes. Such breaches, as I show in the book, allow specters from elsewhere to interfere in the poetic ‘now.’ By reading poems where conjurations take place, for example, I scrutinize the distribution of power between conjurer and conjured, the conditions that facilitate conjurations, but also cases of failed or incomplete conjurations, where the speaker fails to summon specters, as in “Long Ago” (“Μακρυά”), “In the month of Athyr” (“Εν τω μηνί Αθύρ”) or “Waiting for the Barbarians.” Failed conjurations in Cavafy, in fact, reveal more about the constitution of the self or the relation of language with time and history than successful ones.

Cavafy’s spectral poetics does not only have to do with conjuring specters. It can also be traced, for example, in a certain irony that I term “reluctant.” This irony does not stem from a detached, sovereign subject in control of language and history – which is how many critics saw Cavafian irony – but from a vulnerable subject who struggles with conflicting stances, desires, and bodily forms of knowledge that antagonize the desire to control language and the self. In the book, I propose a new approach to irony through affect theory, showing how irony in Cavafy’s writings often emerges from the (impossible) desire to inhabit competing perspectives or truths. The “truths” and positions a subject chooses are often haunted by what the subject represses or is forced to reject. These avoided “truths” become sites of desire that keep haunting Cavafy’s characters and texts, yielding “reluctant irony.” This irony combines the poetic subject’s desire to control language and the desire to submit the text and the self to the haunting of other perspectives and truths, and to embodied forms of knowledge. We see this conflict, for instance, in Cavafian characters who break promises to themselves or act against their intentions (e.g., in “He Swears” / “Oμνύει”). In the book, I actually turn to prose texts that accommodate this irony: in the diary from Cavafy’s first visit to Athens and in his “Philosophical Scrutiny” (1903), in which he reflected on poetic creation. This unorthodox choice reflects my attempt to revisit less studied Cavafian writings, including fictional and nonfictional prose works, many of which are commonly seen as aesthetically irrelevant early musings. In those texts, I argue, we may find fascinating traces of Cavafy’s spectral poetics, which shaped his later production.

In the book you see the spectral is a key aspect of Cavafy’s poetics. But how is the figure of the specter or the notion of spectrality involved in your own mode of reading Cavafy’s work? And what are the implications of this new framework you propose for approaching Cavafy’s work?

Spectral temporality is an aspect of Cavafy’s poetics, but in the book it also gives shape to a mode of reading Cavafy’s work through its afterlives, for which I use the term “pre-posterous.” “Preposterous reading” is inspired by the notion of “pre-posterous history” Mieke Bal proposed in Quoting Caravaggio (1999). Just like spectral time, pre-posterous history disavows linear logic: it is based on an act of reversal that “puts the chronologically first (pre-) as an aftereffect behind (post-) its later recycling” (Bal 1999). The idea that a later “recycling” can have a retrospective effect on the earlier work questions the primacy of the earlier work as origin. A past object does not only have unidirectional influence on its future “recyclings” (interpretations, adaptations, intersemiotic and intermedial translations, citations etc.), but the reverse is also true. A “pre-posterous” reading allows us, for example, to stage a conversation between a Cavafian poem and a contemporary adaptation of that poem to explore not only how the poem shapes its adaptation but also how the adaptation ‘haunts’ back, prompting new readings of the poem from our present.

Cavafy’s only ghost story, “In Broad Daylight” (“Εις το φως της ημέρας” 1985-1986) provides an arena for such a pre-posterous reading in the book. I revisit this story through a scene from Ersi Sotiropoulos’s novel What’s Left of the Night (Τι μένει από τη νύχτα, 2015), a fictional dramatization of three days from young Cavafy’s trip to Paris in 1897. The novel gives me a counterintuitive entrance into Cavafy’s short story, through which I disentangle the nexus of capitalism religion, and modernity, and probe the story’s response to the spirit of industrial capitalism, as Max Weber described it in Cavafy’s time, but also from the vantage point of the future specters of finance capitalism today.

More broadly, approaching Cavafy’s work through spectrality has another crucial implication in the book. Cavafy’s spectral poetics invites us to question the common view of the poet’s linear growth toward poetic maturity, that is, the narrative that sees Cavafy as moving from one early influence to the next (romanticism, parnassianism, symbolism etc.) until he finds his unique voice in his “mature” realist phase, usually set after 1903 and particularly after 1911. Differences between phases of Cavafy’s work are of course undeniable. Yet what bothers me in this evolutionary narrative is that it is often accompanied by disparaging attitudes towards Cavafy’s early writings as frivolous, nonserious exercises or failed experiments in a path to greatness that he achieved much later. By setting aside a strict qualitative distinction between his early writings and “mature” phase, we can see how past influences and ideas in his writing keep returning like revenants in later work, but also the reverse: Cavafy’s modernist poetics, which critics associate with his realist phase, also ‘haunts’ his early writings, pre-posterously, which we can read in a new light through Cavafy’s later production. The suspicion toward linear time that permeates many of his writings prompts us to attend to the interplay of past and future specters and the productive inconsistencies and contradictions this yields in all phases of the poet’s work.

“Cavafy’s poetry remains emphatically contemporary. As critics miss no chance to repeat, his work addresses theoretical, cultural, and political concerns, desires, and anxieties that are at the heart of the twentieth and twenty- first centuries. His poems keep coming back like specters, claiming, and being claimed by, future presents”, we read in the preface of the book. What is it that makes his work both timely and timeless?

Indeed, no other Greek poet has laid a bigger claim on our present and its concerns than Cavafy. Many have broached the question of why Cavafy’s poetry has such an enduring appeal and has been so resonant in cultural, theoretical, and sociopolitical debates that took shape after his death – on modernity, postcolonialism, the relation of self and other, multiculturalism, homosexuality, biopolitics, and many others. Several critics have articulated Cavafy’s continuing appeal in terms of prescience. Cavafy, they argue, predicted or anticipated concerns and discourses that would take shape much later. For example, Gregory Jusdanis writes that Cavafy “was able to foresee the cultural and political milieu of the second half of the twentieth and the first decades of the twenty-first centuries”; “it is as if Cavafy had lived with us and […] jumped back to the early twentieth century to write about our time” (2015).

But what exactly are we claiming when we ascribe prescience to a writer? If we agree that this prescience has nothing to do with Cavafy being some kind of prophet or clairvoyant, we can begin to scrutinize those aspects of his poetics that help us account for his poetry’s haunting force. My own answer is this: The ability of his poems to speak to the future does not issue from any power to predict the future as a prophet or seer – or like the “wise men” who “perceive approaching things” in one of his poems (“Σοφοί δε προσιόντων”). Quite the contrary: it flows from his poetry’s unstable truths, conflicting perspectives, porous contexts, and polyphonic worlds in which multiple voices, quotations, and intertexts refuse to offer a final judgment that steers the future to a single direction. Thus, the claim that Cavafy’s poetry anticipates the future can, paradoxically, be linked to the unforeseeability his poems cultivate: the way they prefigure futures without fully circumscribing them, leaving room for alternative scenarios that may not seem possible (yet) in the present. This was one of the ways in which Cavafy tried to keep endings and death in abeyance; “I do not strongly believe in the absolute value of a conclusion,” he wrote in an essay on Shakespeare from 1891 (trans. Peter Jeffreys).

Yet to claim that Cavafy’s enduring appeal emerges from his poetry’s openness, multivocality, and adaptability to various contexts is only half of the story. His writing also registers the opposite desire: to predict and control the future, formulate historical laws, and shield characters from historical contingency. In many poems, for example, the characters think they know and control how history works, yet they are deluded and fail to control what’s coming. Cavafy’s poems register the desire to foresee, determine, and read the past and the future, but also the opposed desire to make the present, past, and future open or unpredictable – much like the oracles in ancient Greece, who didn’t actually predict the future but gave ambiguous, open-ended messages the receivers could interpret in contradictory ways. Think here of how Nero’s downfall in “Nero’s Deadline” (“Η Διορία του Νέρωνος”) comes from misinterpreting an oracle’s obscure message. I see this conflict as central to Cavafy’s spectral poetics: on the one hand, a desire to control the future, and on the other, a tendency to break historical laws and contexts open and expose them to spectral forces carrying inscrutable ‘messages’ that may point to different futures-to-come.

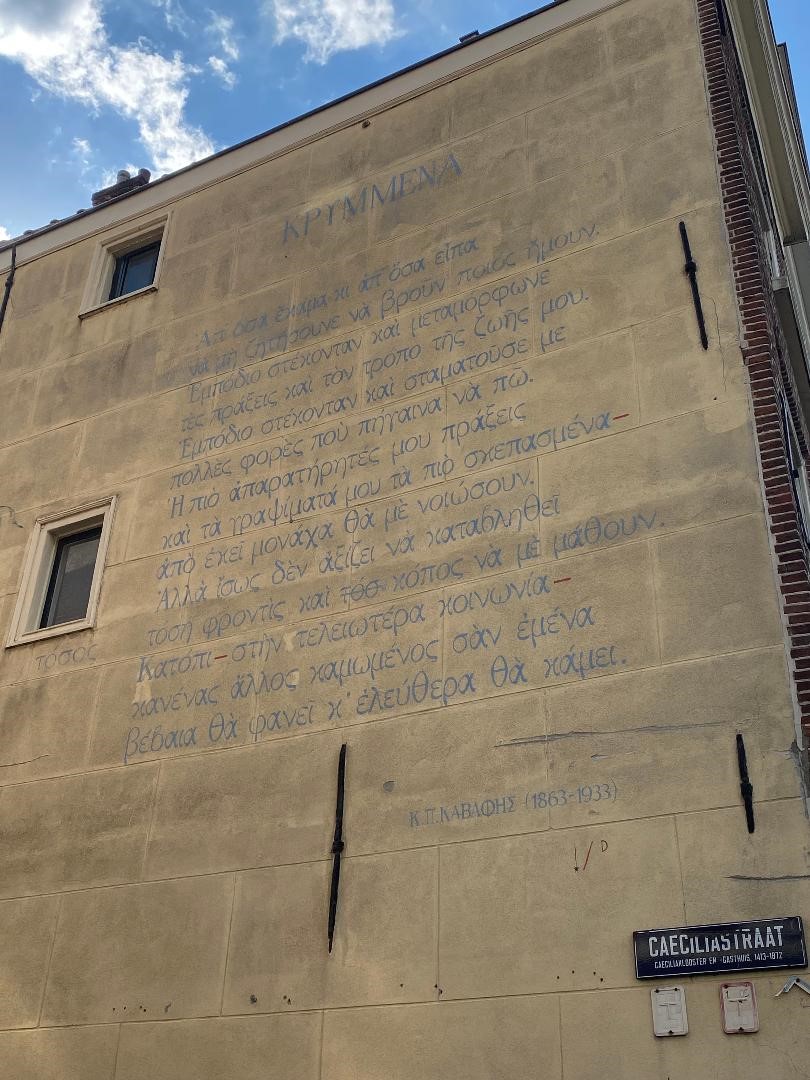

This conflict between control and its abolition can also be linked to the restrictive discourses through which Cavafy sought to express the homosexual self; the restrictions of a language that had no place yet for people “made just like me,” as he wrote in his unpublished “Hidden Things” (“Κρυμμένα”). In this poem he prefigures a community that is not yet there, as Dimitris Papanikolaou has aptly shown in his book on the homosexual Cavafy (2014), but haunts Cavafy’s present from the future. I find it particularly touching that this poem can be seen painted on a wall in Leiden, where I work – not hidden, but shared in public space.

Cavafy’s poem “Κρυμμένα” (“Hidden Things”), figuring since 1994 on a wall on the corner of Turfmarkt street 6 and Caeciliastraat, in Leiden, The Netherlands. Part of the “wall poems” (muurgedichten) project of TEGENBEELD Foundation. Photograph in 2022 by Maria Boletsi

In these ways, Cavafy’s writing makes space for future spectres: languages or concerns that are not yet fully there at the time of writing but may materialize later. This is how I understand his self-description as “a poet of the future generations.” So, returning to the question of what makes his work both timely and timeless, there is, I think, nothing timeless or eternal about the way his poetry haunts our present. His writings, in fact, carry a deep awareness of transience, loss, the inescapability of death, and the idea that nothing lasts forever. His obsessive preoccupation with conjuring the past springs precisely from this awareness of the finality of things, people, and even memory itself, which time and again fails his poetic subjects (think, for example, of “Long Ago” / “Mακρυά”).

Cavafy’s poems keep talking to us because they are not timeless, but vulnerable to time. As I show in the book, this is also how Cavafy saw poetry and its truth: as transient, subject to death and change. The evanescent character of poetic truth makes it more powerful for Cavafy, able to touch the lives of others. Reflecting on the “short-lived” truth that sparks poetic creation in his “Philosophical Scrutiny,” he rejects permanence and eternal life as artistically paralyzing, because, he writes, “things cannot and should not be lasting, for man would then be ‘all of a piece’ and stagnate in sentimental inactivity, in want of change.” Even if a poem is based on “a short-lived truth”—a brief impression or experience— this truth, he writes, “may repeat itself in another life, perhaps with as short duration, perhaps with longer.”

Cavafy’s poetic truth thereby becomes spectral: neither immortal, nor fully mortal. This truth can be momentarily conjured, allowing readers to be affected by it. Truth in poetry “may repeat itself in another life,” Cavafy writes: so there is no certainty that it will. Truth becomes an incalculable revenant: we cannot know when, how, and to whom it will reappear. If poetic truth is spectral, the poet also lacks control over his poems’ future. Poems, too, are subject to oblivion if they fail to speak to future generations in ways that activate their truths anew.

With this awareness, Cavafy releases his poems toward the future, hoping that their “truth” may “repeat itself in another life” but also, he wrote in the same text, “with the consciousness of his work being but finally toys,—at best toys capable of being utilised for some worthier or better purpose.” Despite his extreme control over the composition and distribution of his poetry throughout his life, Cavafy acknowledged the poet’s limited control over poetry’s afterlives. Following Cavafy’s cue, to understand his poetry’s perceived prescience we should not only scrutinize the poems, but also the ways in which these “toys” are recast, recycled, fragmented, cited, translated, interpreted in and from our present, pre-posterously. Cavafy foresees and is foreseen; he haunts and is haunted by future presents. To grasp his poetry’s timeliness, I propose, we should take heed of this two-directional haunting, from past to future and from future to past, time and again. That is why I talk about Cavafy’s address not in terms of timelessness but of spectral time – a time marked by constant returns of the past that are never the same but keep making claims on the present, just as they are claimed differently by each present.

Interview by Athina Rossoglou

* Maria Boletsi is Endowed Professor of Modern Greek Studies at the University of Amsterdam, where she holds the Marilena Laskaridis Chair, and Associate Professor in Comparative Literature at Leiden University, in the Netherlands.

Maria works in modern Greek and comparative literature, literary and cultural theory, cultural analysis, and conceptual history. As a literature scholar and cultural analyst, she brings literature and other modes of cultural expression to bear on contemporary societal challenges and places them in transnational networks and theoretical debates. She is the author of Barbarism and Its Discontents (Stanford UP 2013) and co-author of Barbarian: Explorations of a Western Concept in Theory, Literature and the Arts (Metzler, in 2 vols; 2018/2023). She recently co-edited the volumes (Un)timely Crises: Chronotopes and Critique (Palgrave 2021) and Languages of Resistance, Transformation, and Futurity in Mediterranean Crisis-Scapes (Palgrave 2020), and the special issues “Literature and Public World Making (Parallax, forthcoming in 2024), “Greece and the South” (Journal of Greek Media and Culture, 2022) and “Ruins in Contemporary Greek Literature, Art, Cinema, and Public Space” (Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 2020).

Her latest project focuses on the fictional genre of the weird and its contemporary ‘spillovers’ from literature to ecology, public culture, and politics. Cavafy has been a constant reference point in her work.

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE