It has been called the ‘age of revolution’. The white heat of it came in the decades either side of the year 1800. But it lasted a full century: from the American Declaration of Independence in 1776 to the great national ‘unifications’ of Germany and Italy during the 1860s. Right in the middle of this long ‘age of revolution’ and, as it turns out, the pivotal point within it, comes the Greek Revolution that broke out in the spring of 1821.

Historians have been slow to recognise the key role of the Greek uprising in 1821, and the international recognition of Greece as a sovereign, independent state nine years later, in 1830, in this process that did so much to shape the geopolitics of the European continent, and indeed of much of the world. The Greek Revolution of 1821 and its Global Significance by Roderick Beaton sets out to explain what happened during these nine years to bring about such far-reaching (and surely unanticipated) consequences, and why the full significance of these events is only now coming to be appreciated, two hundred years later.

Greece and the Greeks were indeed the first – the pioneers, the advance guard – to tread a path that in 1830 had never yet been followed to a successful conclusion in the Old World of Europe. Since then their example has been followed by the other modern European states, and many more all over the world. As Roderick Beaton explains, “the Greek Revolution of the 1820s was the first liberal-national movement to succeed in the Old World […] Greeks did not invent the nation-state. But it was in Greece that the experiment was first put into practice in Europe. The outcome of the Greek Revolution turns out to have been the pivotal point on which the whole geopolitical map of Europe tilted, from the eighteenth-century model of multi-ethnic, autocratically ruled empires to the twentieth-century model of the self-determination of nation-states – with consequences for many other parts of the world, too.

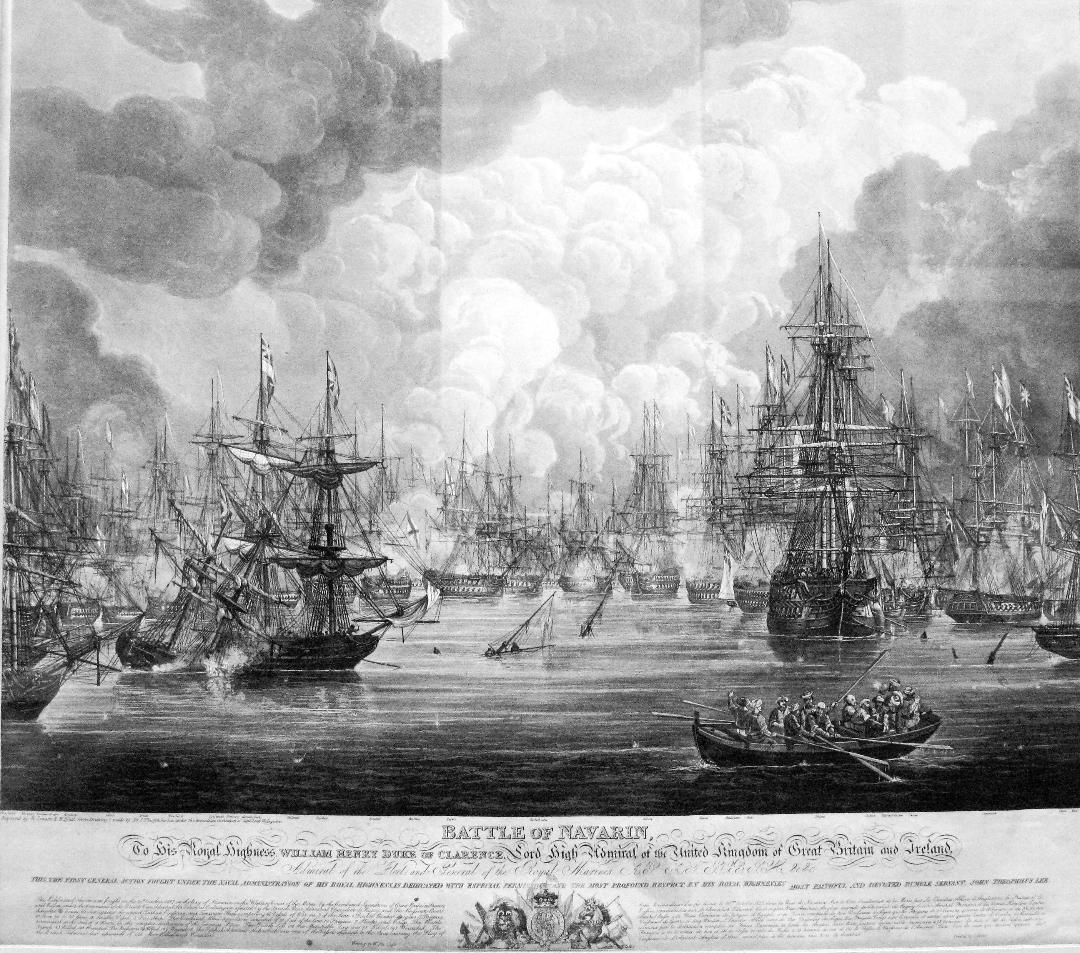

Battle of Navarino. Engraving by Robert William Smart and Henry Pyall, after drawings by Sir John Theophilus Lee, circa 1830. National Historical Museum, Athens

Had it not been for the determination of the Greek people to fight on, the Revolution could not have succeeded as it did. That achievement belongs solely to those who fought and suffered. But no less significant an achievement on the part of the Greek leadership was to mobilize support from abroad. The Greeks welcomed the support of the three Great Powers – Great Britain, France and Russia – whose military contribution has been decisive for the outcome of the Revolution. A case in point is the Battle of Navarino on 20 October 1827, during which their allied forces defeated Ottoman and Egyptian fleets, thereby making Greek independence much more likely.

During the 1820s, philhellenic initiatives sprang up spontaneously in most parts of Europe, and in the USA. The scale of participation is impossible even to estimate. But clearly it was of a magnitude that far outweighed the limited numbers who went to Greece with the expectation that they would join in the struggle there. With justice, the philhellenism ‘of the home front’ has been characterized as a Europe-wide ‘movement’ that mobilized many thousands of individuals and diverse communities. “To be a philhellene,” in the worlds of the French scholar Denys Barau, “was to wish to participate in history in the making”.

Lord Byron. Drawing by P. Stavropoulos, after the painting by Richard Westall

As we read in the Epilogue, the true significance of the events taking place around them was perhaps most accurately, if necessarily imprecisely, divined by those British poets who stand out among the philhellenic movement, Shelley and Byron. In a passage deleted by his publisher from the Preface of Hellas, written in the autumn of 1821, that remained unpublished until 1892, Shelley wrote: “This is the age of the war of the oppressed against the oppressors [… . A ] new race has arisen throughout Europe, nursed in the abhorrence of the opinions which are its chains, and she will continue to produce fresh generations to accomplish that destiny which tyrants foresee and dread”. Ιndeed, as Byron foresaw, what was being achieved by the Greek revolutionaries was to create an entirely new kind of political state that in the future would be emulated throughout the continent.

________

Roderick Beaton grew up in Edinburgh and studied English Literature at Cambridge, before specialising in Modern Greek studies. For thirty years until his retirement he held the Koraes Chair of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language and Literature at King’s College London, and is now Emeritus. Roderick is the author of several books of non-fiction, one novel, and several translations of fiction and poetry, all of them connected to Greece and the Greek-speaking world. He is a four-time winner of the Runciman Award, and his books have been shortlisted for the Duff Cooper Prize and the Cundill History Prize.

He is a Fellow of the British Academy (FBA), a Fellow of King’s College (FKC), and Commander of the Order of Honour of the Hellenic Republic. From 2019 to 2021 he served as a member of the Committee “GREECE 2021”, charged by the Greek government with overseeing events commemorating the 200th anniversary of the start of the Greek Revolution in 1821. Beaton was recognised by the Greek State with the Commander of the Order of Honour of the Hellenic Republic in 2019.

A.R.

Read more: Rethinking Greece | Roderick Beaton: “Europe is unthinkable without Greece”; Reading Greece: Aiora Press, a Publishing House that Promotes Greek Literature beyond National Borders

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE