The global meetings and events industry turns its spotlight on Greece with the hosting of the Annual Meeting and General Assembly of the International Association of Professional Congress Organisers (IAPCO) at the Athens Concert Hall (Megaron) from 25 to 28 February, reaffirming the country’s growing momentum and its strategic position on the global conference map. More than 150 leading professionals attend the event, delivering a strong vote of confidence in Greece, which has long invested strategically in conference tourism. The sector fuels destination development, with the conference delegates and visitors spending five to seven times more than the average traveler. IAPCO represents more than 95 companies employing over 23,000 professionals across 185 countries. The economic impact recorded by its members for 2025 exceeds €16.8 billion.

The conference is themed “The Odyssey Reinvented,” linking Greek mythology with the challenges the sector has faced in recent years — a true odyssey marked by the pandemic, geopolitical turbulence, economic uncertainty, rapid technological advances, and growing sustainability demands. The conference is organised by the four certified IAPCO members in Greece — AFEA Congress, Convin, Era & Erasmus — and is supported by the Ministry of Tourism, the Greek National Tourism Organisation (GNTO), the This is Athens Convention Bureau, as well as leading organisations and companies across the entire conference organisation ecosystem.

The global IAPCO community gathered at the Acropolis Museum for the official Welcome Reception, marking the start of IAPCO AM&GA Athens 2026 under the theme “The Odyssey Reinvented.” The evening began with an exclusive private tour of the Museum, offering delegates the opportunity to experience one of Greece’s most significant cultural landmarks. (Photos: facebook.com/IAPCO)

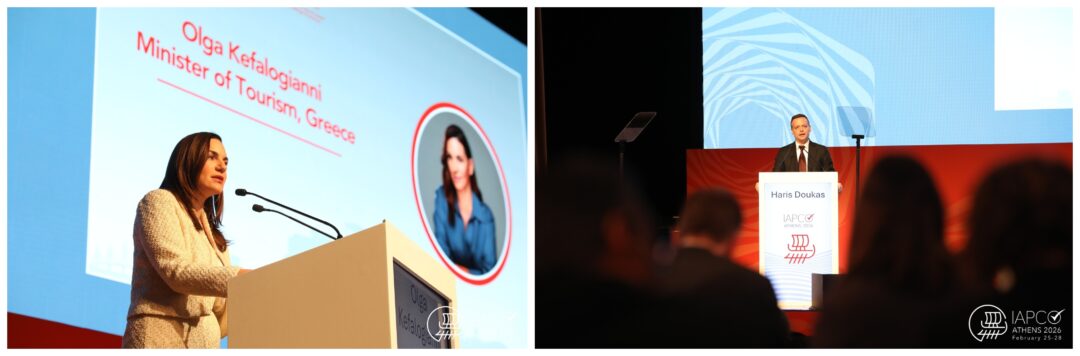

The Opening Session was honoured by the presence of Olga Kefalogianni, Minister of Tourism of Greece, representing the Prime Minister of the Hellenic Republic, and Haris Doukas, Mayor of the City of Athens, underscoring the high importance the destination places on the global meetings industry and recognising its far-reaching economic, societal and intellectual impact. (Photos: facebook.com/IAPCO)

In her address, the Minister of Tourism, Olga Kefalogianni stressed that “Greece is steadily strengthening its position as a modern, competitive, and outward-looking destination for meetings, conferences, and major international events”. The Minister welcomed the delegates to Athens, noting that the selection of the Greek capital to host this event constitutes a vote of confidence in the country and recognition of its growing momentum in the field of international conferences and events. Furthermore, she emphasized that through continuous investments, enhanced air connectivity, and high-level services, the city offers a comprehensive and attractive environment for hosting international meetings and high-standard events. The hosting of the IAPCO General Assembly in Athens marks a significant milestone for Greek tourism and confirms the country’s commitment to strengthening conference tourism. At the same time, the Minister underlined that Greece has a modern and constantly evolving ecosystem for the MICE sector, featuring contemporary conference centers, high-quality services, and specialized human resources. Ms. Kefalogianni also highlighted the country’s unique cultural dimension, noting that cultural venues provide distinctive options for hosting events.

(Source: mintour.gov.gr)

The conference was preceded by the IAPCO Council Meeting, which was held at the Grand Hotel Palace in Thessaloniki, hosted by the Thessaloniki Convention Bureau, from 21 to 24 February (Photo: facebook.com/IAPCO).

Speaking to the an interview with the Athens–Macedonian News Agency, IAPCO CEO Martin Boyle pointed out that Greece is seen as “a kind of hub” for the conference market and an attractive destination. “You don’t need to sell the name ‘Greece’ to an international delegate. The moment someone says ‘Greece,’ they already have in mind an idea of what that name means to them (…) and I think that idea is very positive. On the other hand, I believe that when someone looks at other destinations, they even struggle to define what their brand identity is for an international participant. Here (in Greece), that brand is very strong. So there is a real opportunity for you to capitalize on it”. According to Mr. Boyle, the reduction in duration, combined with a focus on a specific perspective, creates exciting opportunities for conference destinations, which could host more medium-sized conferences within a week instead of fewer large ones. “There are more opportunities for medium-sized conferences, and for cities like Thessaloniki, I believe that a number of 1,500–2,000 delegates is really good,” he noted, while adding that the role of safety for conference participants is becoming increasingly important. In this context, European destinations remain at the center of attention.

(Source: amna.gr)

IAPCO AM&GA Athens 2026. “The Odyssey Reinvented” – A Very Human Journey Toward the Meetings of Tomorrow. Athens is a destination with forward-thinking heritage, vibrant urban culture, and world-class meeting facilities, offering excellent connectivity by air and sea, and sustainable and fast transport from the airport. With its impressive rise in the international meetings industry, Athens has already been established on the global map within the top 10 most popular destinations for congresses. (Source: iapco.org)

IAPCO President, President & CEO of AFEA CONGRESS, Sissy Lignou stated in an interview with the Athens–Macedonian News Agency that the awarding of the international IAPCO conference to Athens is proof of the recognition of the professionalism and capability of Greek organisers to host an event of such high calibre. It also signals trust in the professional core of the international meetings market (PCOs) and confirms that our country can deliver a top-tier industry event in terms of experience, infrastructure and stakeholder collaboration.

“We chose the theme “The Odyssey Reinvented” in order to highlight not only the importance of the final destination on the way to achieving our goal, but also the great significance of the journey itself and the ‘experience’ that the organisation of conferences and events can create for each visitor or participant. We present the ‘journey’ as an opportunity, beyond the challenges,” Ms Lignou noted.

As the first Greek president of the international organisation, Ms Lignou believes that Greece possesses a deep tradition of hospitality, strong scientific capital, a dynamic academic community, and highly adaptable professionals. “Our scientists are recognised by international organisations, which turn their attention to our country for hosting their national conferences and events. Greek entrepreneurs excel abroad, making Greece an attractive hub for corporate meetings. In recent years, Greek PCOs have demonstrated that they can operate according to international quality standards, incorporate sustainable practices, and leverage technology in meaningful ways,” she notes. She also emphasizes that “Greece can influence global trends not only as an appealing destination, but as a ‘laboratory’ of innovation in conference and event design. Our country’s authenticity can once again highlight the importance of the human element and genuine interaction in a world dominated by technology.”

(Source: amna.gr)

This is Athens – Convention & Visitors Bureau, established in April 2008, is the business division of the city’s international brand and advances Athens in the global tourism and meetings industry. As part of Develop Athens S.A., the City of Athens’ development agency, it strategically attracts international tourism and investment, leveraging the city’s unique assets and cultural heritage. It has been recognized multiple times as Europe’s Leading City Tourist Board at the World Travel Awards. Athens has been awarded “World’s Leading Cultural City Destination” for 2024 by the World Travel Awards, continuing its recognition as a top destination.

Thessaloniki Convention Bureau (TCB)is a non-profit member-based organization set up by a group of private companies, leading partners of the events and conventions industry, acting as intermediary link between meeting planners and local service providers, conference centers, venues, hotels, PCOs & DMCs. High professionalism in meetings organization, attractive venues, high standards hotels and a large number of relevant to the industry services, add value the city’s charming profile.

TAGS: ATHENS | THESSALONIKI | TOURISM