DAEDALUS, the computing core of the AI Factory Pharos, is the new supercomputer expected to transform Greece’s research and innovation landscape. It is now entering the final phase of its implementation: the entire system has already been assembled at HPE’s factory in the Czech Republic and is undergoing full technical inspection before being transferred to its final installation site at the Lavrion Technological and Cultural Park of the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) (cover photo: Preparation of the Lavrion facilities).

The first photographs of the new DAEDALUS supercomputer have already been released, generating waves of anticipation among those awaiting the start of its operation at the Lavrion facilities. As shown in the photographic material, the facilities are currently being prepared to host it later this summer. This is a highly complex construction consisting of specialized cabinets with direct liquid cooling and high power specifications, integrating more than 2,000 powerful NVIDIA Grace Hopper (GH200) superchips, specifically designed for large-scale artificial intelligence applications. At HPE’s laboratories, extensive operational testing of the individual units and their interaction as a unified system is currently underway, ensuring that before its transfer and installation in Lavrion, its stability and performance under real workload conditions have been fully validated.

Based on measurements already carried out, DAEDALUS is expected to reach a computing power exceeding 89 quadrillion arithmetic operations per second (89 × 10¹⁵ FLOPS in double precision). Compared to home computers and typical professional systems, this corresponds to performance levels millions of times faster, enabling it to solve computational problems in hours or days that would require weeks or months on conventional machines. The installation of DAEDALUS in Greece marks the first time such a powerful system is hosted in the country and is expected to position the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) and Lavrion among Europe’s leading computational infrastructures, serving as a regional hub in Southeastern Europe.

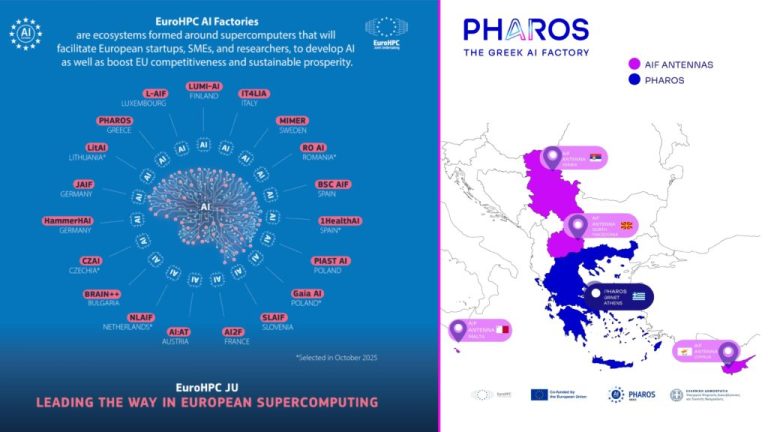

The Greek Artificial Intelligence “Factory” PHAROS is becoming a regional AI hub in Southeastern Europe, as it will be connected with four AI Factory Antennas in Cyprus, Malta, North Macedonia, and Serbia (Source: www.ekt.gr/en )

Pharos, the Greek AI Factory

The Minister of Digital Governance, Dimitris Papastergiou, speaking to the Athens–Macedonian News Agency, stressed that “DAEDALUS is not just another technical project. It is a strategic investment of national importance that places our country at the core of Europe’s computing and technological power. At a time when Artificial Intelligence and data determine economic and geopolitical influence, Greece cannot remain merely a consumer of technology. DAEDALUS gives us the ability to produce knowledge, innovation, and high value-added applications here, in our own country”.

The Minister of Digital Governance continued: “As the computing core of the AI Factory Pharos, it will provide startups, universities, and public institutions with access to advanced infrastructure that until now was the privilege of only a few countries. From healthcare and sustainable development to the Greek language and culture, we are creating the conditions for Greece to shape developments — not merely follow them. With DAEDALUS, we are building a new pillar of digital sovereignty. We are putting into practice our choice for an economy of knowledge, technology, and extroversion, with a meaningful and active role in the European Artificial Intelligence ecosystem.”

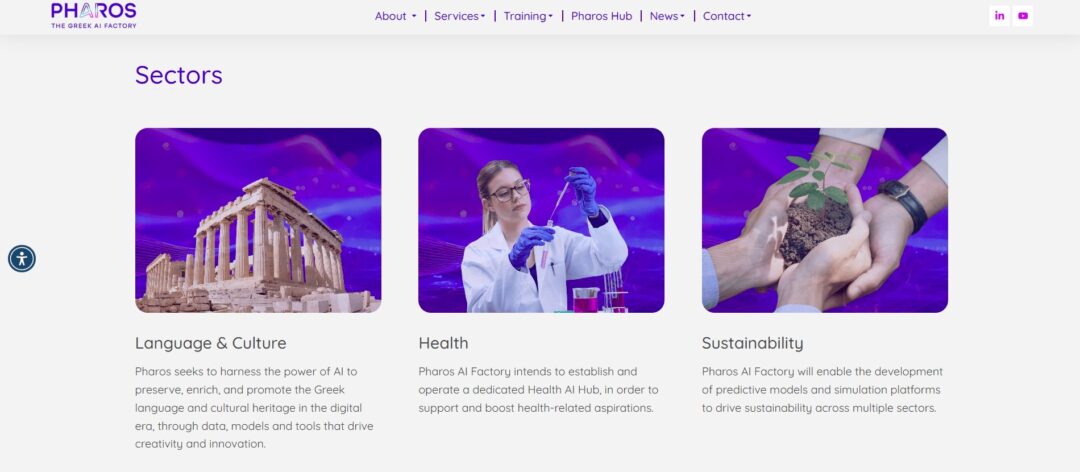

The organization and operation of the system are not limited to the “machine” itself. It constitutes an integrated infrastructure in which the supercomputer will serve as the core of Pharos, an AI Factory that will provide the service layer: access rules, support, tools, data management, and human expertise. Pharos aims to make supercomputing power accessible to research centers, universities, startups, and the public sector by offering services and technical assistance so users can leverage high-performance computing safely, compliantly, and efficiently. Technical matters such as sensitive data management, anonymization, preparation of AI-ready datasets, and the implementation of proper access policies will be handled through the Pharos service ecosystem, reducing barriers for businesses and researchers.

The practical significance of the infrastructure is immediate and multi-layered. For Greek startups and SMEs, DAEDALUS and Pharos mean access to computing power and technical support that until now were available only through costly commercial cloud services or with significant delays when accessing international centers. This can reduce development costs and accelerate AI model training and optimization cycles, enabling a faster transition from proof-of-concept to functional prototypes and pilot applications in sectors such as healthcare, public services, energy, and the environment. Universities and research institutions gain access to infrastructure for complex simulations and large-scale experiments, reducing the need to send workloads to foreign platforms and strengthening opportunities for collaboration with industry.

In the healthcare sector, for example, a Greek startup will be able to rapidly train large models that prioritize images from emergency cases—such as X-rays or CT scans—and integrate anonymization and secure data management tools in order to test and validate clinical applications much faster than has been practically feasible until now. In the public sector, access to computing power at a national scale opens up possibilities for improved data analysis, faster crisis response, optimization of energy grids, and applications for environmental protection and natural resource management.

PHAROS AI Factory, Greece’s national ecosystem for accelerating Artificial Intelligence innovation, participated in Athens Digital Health Week 2026, held on 16-20 February 2026 in Athens

The installation and full operation process follows a specific timeline: DAEDALUS will be installed in Lavrion in the summer of 2026, while full operation and the provision of services to the country’s innovation ecosystem through Pharos are expected in the autumn of 2026. The project is being implemented under the auspices of the National Infrastructures for Research and Technology Network (EDYTE S.A. – GRNET), with scientific and administrative oversight from leading figures in the field, including distinguished professors and representatives in European programs such as EuroHPC, as well as from the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA). The close collaboration among academic, technical, and administrative bodies, along with the involvement of EU funding instruments and the Greek public administration, aims to ensure that the investment will generate multiplier benefits for the economy and research.

(Source: www.amna.gr : “DAEDALUS – “Building” the Heart of Pharos: From Assembly to Installation in Summer 2026”, Photos: Ministry of Digital Governance)

DAEDALUS supercomputer of GRNET at the Lavrion Technological Cultural Park of the NTUA (animation)

Read also:

Daedalus Supercomputer to elevate Greek research to new heights

TAGS: ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE | DIGITAL TRANFORMATION | INNOVATION | RESEARCH | SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY