The web portal Study in Greece is campaigning for the promotion and international visibility of Greek Universities and the comparative educational advantages of our country. In particular, the campaign focuses on the foreign language study programs that Greek Universities offer to Greek and international students. The initiative is supported by the General Secretariat of Higher Education of the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs and the General Secretariat for Greeks Abroad and Public Diplomacy of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs. In this context, a number of educational programs and actions are presented in detail on a regular basis, such as undergraduate and postgraduate programs, summer schools etc, to inform international students about the many foreign language options offered by Greek Universities.

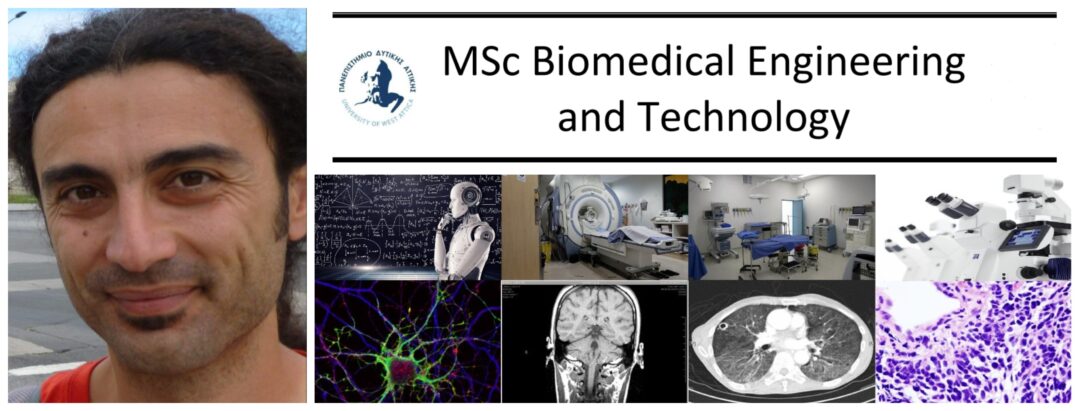

Dimitris Glotsos is a Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of West Attica and the Director of the MSc Program “Biomedical Engineering and Technology”. His research interests include pattern recognition, medical image processing and analysis, bioinformatics and microscopy.

Study in Greece interviewed Professor Dimitris Glotsos on the MSc Program “Biomedical Engineering and Technology”, its features and what it has to offer to international students.

Please provide us with an overview of the MSc in Biomedical Engineering & Technology’s structure and main research areas.

The MSc in Biomedical Engineering & Technology is a 1.5-year full-time program (three academic semesters) hybrid program (online + on-site) requiring 90 ECTS for completion.

- Semester 1 & 2: Taught courses covering core biomedical engineering topics such as instrumentation, medical imaging, diagnostics, and technology applications.

- Semester 3: Dedicated to the diploma thesis, a full-scale research project supervised by faculty.

The curriculum includes modern areas like medical imaging, biomedical instrumentation, artificial intelligence, in-vitro/in-vivo diagnostics, bioethics, and modern biomedical systems.

What would you say is the main characteristic of your program that makes it more appealing to international students?

The program is taught in English and uses internationally relevant biomedical engineering content, making it accessible to students from around the world.

It offers a balanced combination of theoretical foundations, hands-on laboratory experience, and active research involvement, complemented by on-site visits and specialized seminars delivered by practicing biomedical engineering professionals.

We believe that this integrated approach supports graduates in developing the skills required for success in both academic and industrial environments.

Tuition fees are competitive, while the overall cost of living is significantly reduced due to the hybrid structure of the program: students are required to be on campus only during the final month of each semester, with the remainder of the program delivered online.

Could you please elaborate on the interdisciplinarity of the MSc in Biomedical Engineering & Technology?

Theprogram bridges engineering, life sciences, and healthcare. Students apply engineering principles to medical challenges, integrating knowledge from:

- Medical imaging and data analysis.

- Informatics and artificial intelligence.

- Biological systems and diagnostics.

- Electronics and instrumentation.

This interdisciplinary mix prepares students for diverse roles in medical technology, research, and health innovation.

Does the program feature any additional events, activities or conferences that could further attract and engage students?

One of the core activities of the program focuses on active interaction with the biomedical engineering labor market through on-site visits and specialized seminars organized in collaboration with biomedical engineering professionals. Students have the opportunity to visit hospitals, research centers, companies, and specialized laboratories, gaining first-hand experience of the role of the biomedical engineer in everyday professional practice.

Are there opportunities and prospects for collaborations with different universities, in Greece or abroad?

Yes — the program has cooperation links with Greek and international institutions. For example, partner universities include institutions in the UK, Portugal, Spain, USA, Romania, and Germany.

What would you say to an international student who is considering pursuing studies in biomedical engineering and technology in order to choose your program?

If you come from a different scientific or engineering background and want to transition into biomedical engineering, this MSc is an excellent choice. It is designed as a conversion program, offering a strong introduction to biomedical engineering fundamentals. Students gain essential theoretical knowledge, hands-on experience, and exposure to applied research within a European academic environment. The program builds the necessary background for careers in biomedical technology, healthcare engineering, research, or further doctoral studies.

TAGS: STUDY IN GREECE