Georgia Zachari was born in Athens in 1994. She studied Art History at the School of Fine Arts, where she completed her thesis titled “Representations of the urban landscape in contemporary Greek comics: Athens and Thessaloniki”. Since then she has chosen to draw comics with cities herself rather than write about others. She began publishing her work in 2017, and in 2019 she collaborated with Giorgos Goussis and Panagiotis Pantazis on the comic book Festival, for the 60th anniversary of the Thessaloniki Film Festival.

Stella Stergiou was born in Athens in 1992. She completed her studies at the School of Architecture of NTUA, where her final research was on comics in relation to the urban landscape. She entered the comic market in 2017 with The Little Prince (Polaris Publications) and since then she has preferred to set up fictional stories within two-dimensional spaces rather than three-dimensional ones for real people. Today she collaborates with several publishing houses (In the Forest, Patakis Publications, Stolen Ears, Mikri Selini Publications, Garis, Patakis Publications) and draws colourful figures from her home in Belgium.

You have turned two classical Greek books – Wildcat under glass and Near the rail tracks by Alki Zei into graphic novels. Tell us a few things about this venture of yours.

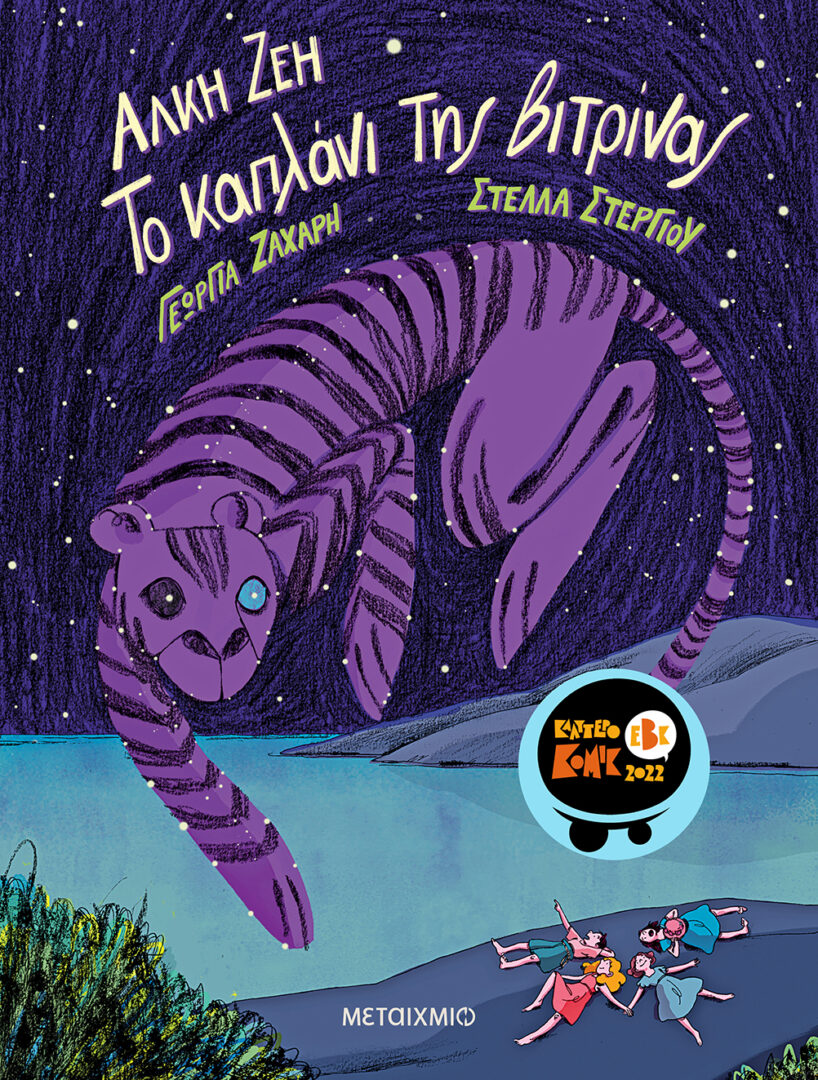

The story of how our collaboration started is one of our favourite shared anecdotes. In the faraway 2018, when our friendship started taking shape, we were discussing projects we are passionate about. Georgia was saying that maybe we have enough adaptations of classics going around but, without skipping a beat, she added that her dream job would be to adapt Wildcat under glass. Fast forward to 2020, Stella received a call from Thodoris Tsolis, editor at Metaichmio publications, asking her if she would be interested in turning Alki Zei’s classic wildcat into a comic. Stella was too stunned to speak. She left Thodoris on hold, and immediately called Georgia to make her an offer neither of them could refuse. After a round of joyful screaming, Stella called Thodoris back and this is how our deep dive inside Alki Zei’s world started.

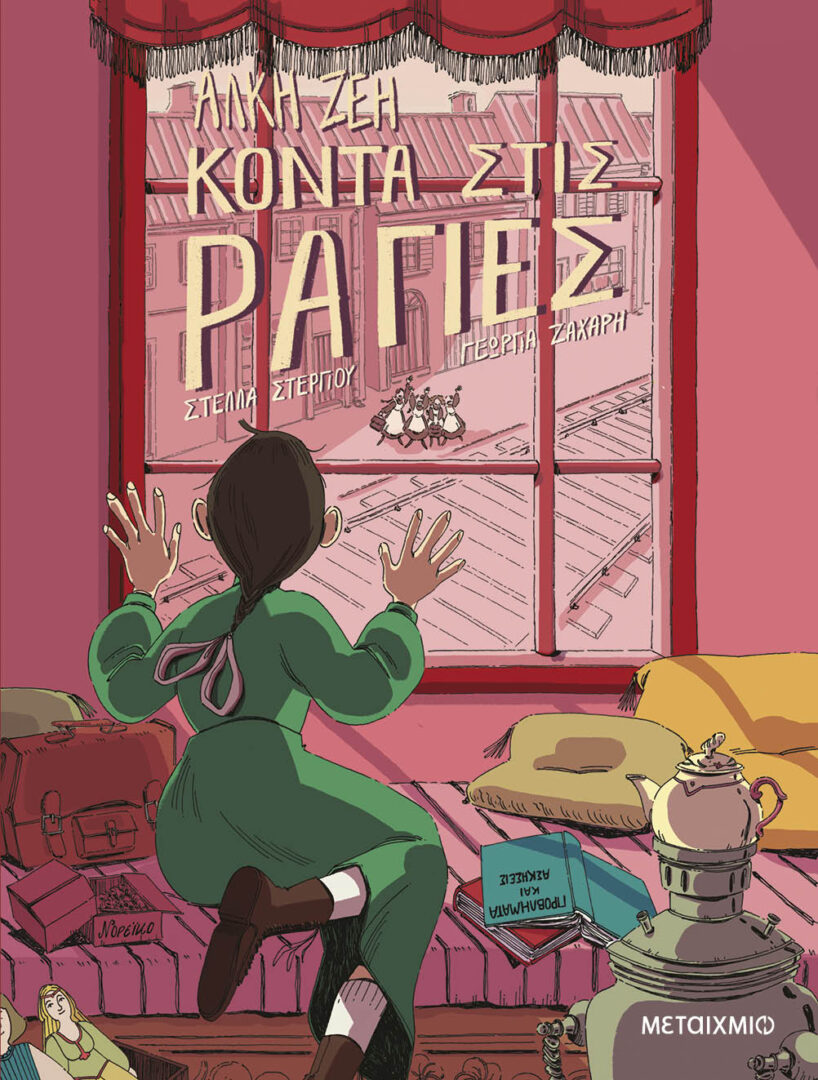

Wildcat under glass, the comic, was warmly received by both long-time fans and new readers. Its success led Metaichmio to commission a second adaptation from Zei’s work, but this time we were able to choose which book. Unanimously, we said Near the rail tracks, because of the very distinct voice of the protagonist, its powerful narrative of girlhood friendships, and its unwavering message of standing up for yourself and those around you in the face of oppressive regimes.

Both books are truly four-hands comics. Whereas comics are often created by one writer and one illustrator, in our case, every single page – storyboarding, dialogue, pencilling, inking, and colouring – was a shared effort. Creating a comic is a long and often solitary process, filled with moments of doubt and second-guessing. Our way of working might be unusual, but having your best friend sitting across from you, offering the trust in your work that you might be struggling to find yourself, is a unique booster. It’s what helped us push through, and emerge not just as stronger storytellers, but as even stronger friends.

Which were the main challenges you faced during this process?

One would have thought the main challenge would be to adapt such a well-known, beloved author. We have often been asked about whether that made us scared or anxious. The thing is, we both loved Alki Zei so much that we felt no such stress. We knew we were the right people for the job because of our sheer enthusiasm for it.

Of course, that doesn’t mean everything about the job was easy. We had to adapt to working with each other on a daily basis and to agree on a drawing style that would work for us both. A specific problem we faced was that due to covid restrictions, we could not travel to Samos, and due to lack of time and resources, we could not travel to Vilnius (where Near the railtracks is set). This meant we had to work a lot more in order to find historical references of buildings, spaces, clothes, etc. and that sometimes we had to let go and just follow our instinct.

Is there something from the original work that is lost in the process of turning it into a graphic novel? What is there to be gained?

It’s a given that when adapting a story from one medium to another, some things inevitably change. In book-to-comic adaptations, one of the biggest challenges is deciding what to leave out for the sake of brevity (otherwise, each of our comics would be 300 pages long).

One such scene we had to cut from Wildcat Under Glass is when Melia, the protagonist, starts becoming friends with Alexis, a boy in her class. While walking home from school, he invites her to see his family’s cat. When they get there, he seems to search for the cat but comes back empty-handed. We never learn if his family even had a cat, or if he just wanted to be friends with Melia but didn’t know how. It’s a scene that seems redundant, but that carries a lot of character, and that gives the text room to breathe. Sadly, such scenes are often the ones that have to go.

On the flip side, we found that images often grant clarity to meaning. A lot of people who read Wildcat the novel as children remember it as being about kids enjoying their fun summer adventures, as this is the most relatable part for people growing up after the 70s. Some are surprised to realize that it’s actually about the rise of fascism and the newly born 1930s dictatorship. However, when put into images – the burning of books, the kids doing Nazi salutes, the violence inflicted by the police – this becomes clearer and permanently etched onto the reader’s mind.

Do graphic novels constitute an effective way to introduce classical literary works to younger generations? What’s your feedback so far?

Yes! We are also part of a younger generation and we feel that way about a lot of books ourselves. Modes of expression change over time and that is not a bad thing. There are several classics that we personally had no plans to read that we got to know through their adaptations into comics (such as the Lord of the Flies), and many which we understand are important, but whose writing style is just not as appealing anymore. This has probably been happening for ages.

Zei’s style still feels very fresh, and the stories remain relevant, but we also understand that sometimes wonderful books are forced upon kids in a way that makes them seem extremely dull. It makes us very happy to have adapted two books that mean a lot to us in a way that might make them appear more intriguing, and to have introduced a writer we love to more possible fans. A lot of kids we’ve met in schools or comic conventions have told us they enjoyed our work, and a few of them also felt motivated to read the original novels as well.

Still, when it comes to these particular books, our primary concern isn’t just promoting a love of reading. What matters most to us is creating opportunities to talk with kids about fascism, antifascism, and what freedom and solidarity truly mean.

In the era of online communication, which has deeply affected reading preferences, how important is the role of illustrators, and more specifically comic book artists, in rendering books more appealing?

Online communication has definitely changed the way we engage with the written word. But, it has also opened up incredible opportunities for comic artists. It’s made it easier to explore new formats and techniques within the medium, and it’s also made it far more accessible for artists to share their work with a wide audience.

Today, just as many digital comics circulate online as printed ones, often using the format in ways that are completely distinct from traditional books. The most important factor, though, for comics of whatever form to be appealing, is accessibility. And in that regard, online platforms can be powerful tools.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE