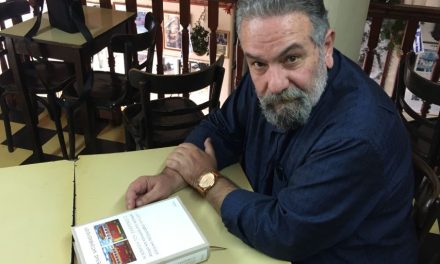

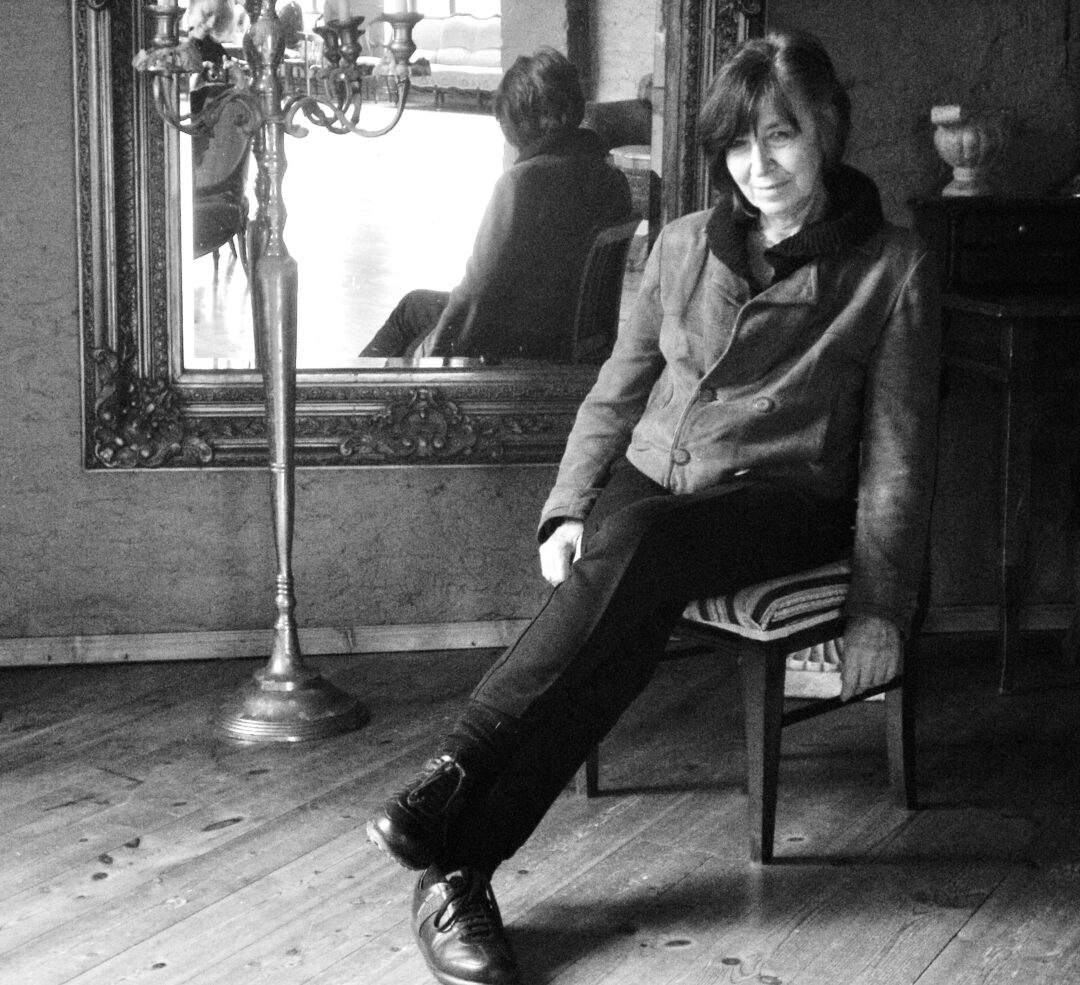

Ismini Karyotaki was born in Ioannina. She studied architecture at the National Technical University of Athens and stage design at Beaux Arts in Paris. She worked as an architect in Paris and Athens and as a set designer in the theatre and the cinema. She has written seven books, including novels, novellas and a chronicle. Her latest novel titled Fugitive I Was Not (Potamos, 2022) received the State Award for Best Novel.

Your latest writing venture Fugitive I Was Not (Potamos, 2022) received the State Award for Best Novel. Tell us a few things about the book.

Through a systematic time reversal of the past of its heroes, Fugitive I Was Not attempts to trace what it means to live in Greece in the post-war years, following the 1967 coup up to the years after the restoration of democracy in the country. What does it mean to live in the Greece during these so similar yet quite different socio-political conditions?

The novel hints at the reconciliation between its heroes or their estrangement, while leaving the vital questions that torment them open to this day.

The book takes us back to a historic journey from the Greek civil war, the dictatorship and the present. Where does history meet fiction in your writings?

Both the attitudes and the relationships of the three main characters in our novel – Spilios, Erifili, and Flora – are tested to the breaking point. In other words, they find themselves on the razor’s edge, influenced primarily by the historical events they have each experienced, depending on the respective unfolding of their personal histories.

The giant dining room in the centre of the mansion where Spilios and Erifili are hosted will be transformed from a theatre of a reconnaissance foreplay into an open front of confrontation between hosts and guests.

In this same dining room, Spilios – who has been tortured and imprisoned during the dictatorship – will find himself confronted with the photographs of the royal couple, Paul and Frederica, as well as with the initial attitude of Erifili after her consent at Flora’s promptings.

Spilios, also, tracing the space of the room where he stays for one night only, will discover Flora’s humanitarian attitude during the civil war through hidden photographic documents. He will even go so far as to clash with himself and consider perhaps reconciling with the mansion’s hosts.

Flora, despite the richness of her emotions, will forever be trapped in the silencing of the question marks that overwhelm her. Questions related to the civil war, as she herself has experienced it, but also to her personal love story.

How are the notions of time and place imprinted on you work?

Space and time are among the main protagonists in my novels. I arrive at time under the pretext of searching for place and I discover space under the pretext of searching for time. I explore a house by approaching its history, I associate with the people who inhabit it by assimilating their experiences and I get lost in the city while getting lost in its history; I search for a street by looking for the timeless events that ran through it or I cross a bridge by reflecting on the chronicle of its construction.

“The figures of the hunted, the fugitive, the exile, the illegal, the mistress, the bohemian, the cosmopolitan, all these characteristic motifs of the flaneur, the wanderer – according to Benjamin – have significantly influenced my writing and on the pages of my books they are transformed into heroes”. Tell us more.

I first read Benjamin’s Flâneur by Alexandria Publications in 1994, motivated by my professional activity: being an architect, I was at that time working on spatial planning studies all over Greece. I once again resorted to the book in 2005, this time motivated by my participation in the World Architecture Conference in Istanbul on the theme Cities: the great bazaar of Architecture. Returning to Athens and enthralled both by the subject and by a personal experience within the city, I enthusiastically engaged in writing my fourth book, Attempted Encounter. A novel in which the hero, Orhan, moving as a flâneur in the city – Istanbul – meets by chance with a woman, Clara, also a flaneur. Their meeting evolves into a frantic chase – erotic I would say – through the unfamiliar streets of the city. In my following books, On the Streets, Without Taximeter, The Bandits of the Black Humor Anthology, and my last, the award-winning Fugitive I Was Not, the flâneur returns, changing face each time, yet persisting in his wanderings.

The figures of the bohemian, the dandy, the outlaw, the lover, the hunted, the exile –all these characteristic traits of the flâneur according to Benjamin – have greatly influenced my writing; transmuted into heroes, they appear on the pages of my books. To conclude with, for me, city streets are absolutely necessary – and as Hoffman says – the possibility of the mere sight of people – while crossing them – interests me more than anything else. It is also the reason, after all, that pushes me to write in places of gathering, in cafes mainly, but also in squares, in parks, where the music of human voices accompanies me.

What about language? What role does language play in your stories?

The truth is that I have not done the corresponding studies – I mean literary or even theoretical studies; as I already mentioned I come from the field of sciences – although the existence of a strict dividing line between the sciences is questioned by many experts. But here I would like to add that I have some particularly good relations with music, and not only as a listener; in addition to singing as a child, I studied the guitar as an adult. For me, music is language and language is music.

During the writing process, I read and reread many times – infinitely, I would say – what I have written – both silently and aloud – and going back to the flow – not always to the meaning – but to the words and the sound of their flow – as if it were a piece of music – I correct and restructure the flow of the speech.

In addition to being a writer, you are an architect as well as a painter. How do these multiple qualities interact and leave their mark on your writing?

The School of Architecture in which I studied is a hive of the arts, so to speak. From architecture I moved effortlessly to painting and then to set design – to theatre and cinema. Words often intruded my paintings – da Vinci is certainly to blame – some of them were published in a book. Over time words multiplied and overflowed to the point where they overshadowed painting and my books eventually became tied to writing. Along the way I learned that art is one: arts are communicating vessels. When, in an interview of Dimitri Hatzis, I read that he treats each of his writing projects as a construction, I was surprised, as I thought only people like me – coming from a background in science or visual arts – would have a similar view of writing.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE