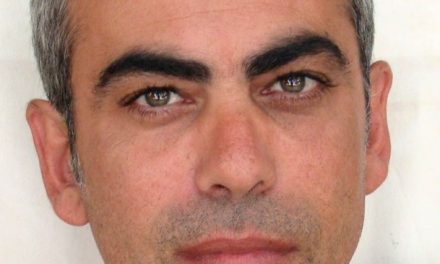

Markellos Chryssicos (full name: Markellos Chryssicopoulos) is a conductor and musician who has dedicated himself to a very particular endeavour: the historically informed performance of early music, especially Baroque. His musical education began at a young age. After originally learning piano, he went on to study the harpsichord. Once the most important keyboard instrument, the harpsichord lost favour to the piano in the 19th century, but knew a revival in the 20th century, especially after the 1950’s. Chryssicos, with musical studies in Athens, Paris and Geneva, acquired a vast and solid repertoire ranging from early madrigals to Mozart operas. His great passion however remains Baroque music.

As a musical assistant and vocal coach, Chryssicos has participated in various award winning recordings and productions. He is a harpsichord virtuoso and, above all, an internationally acclaimed conductor. His production of Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppea as well as Salomé, based on Stradella’s San Giovanni Battista, have been hailed as highlights of the Athens Festival. He has conducted the Venice Baroque Orchestra in a double CD recording (L’Olimpiade – the opera of the Olympics). As conductor, he often collaborates with Armonia Atenea, the Athens State Orchestra, the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra and other ensembles.

Perhaps his most interesting project is the founding of Latinitas Nostra, an ensemble performing Early Music, mainly Baroque, in a historically informed way; apart from the harpsichord and the church organ (which Chryssicos also masters), they use theorbo, viola da gamba (viol) and other Baroque instruments. Both their recordings and many performances have earned them stellar reviews, with their trademark perhaps being the unexpected, risky musical pairings they often attempt: In their performance “A voyage into the Levant”, Elizabethan composer John Dowland meets secular Ottoman music while in “…for I will soon be laid in the earth…” French Baroque merges with the Greek urban folk rebetiko. We met with Markellos Chryssicos* and talked about his career, his upcoming projects and the relationship between Greek and Baroque music.

Let’s start with your imminent projects; first, J.S. Bach’s St John Passion at the Athens Concert Hall on April 1st. Will there be experimentations, as there were in some of your recent works, or will this be a faithful rendition?

No, there will be no experimentations. Remaining “faithful”, however, is another matter altogether, given that this work was written to be performed in a very different place, of different size and acoustics, for a very different occasion: it was performed for the first time in 1724, at Good Friday Vespers at St. Nicholas Church, which means it was aimed at a congregation gathering to fulfill a religious duty. So, regardless of the effort of the musicians or me, as a conductor, to recreate the original performance, we are limited by the reality of totally different acoustics and a dissimilar occasion, a different, secular audience, probably much less familiar with the narration in the Gospel of John. Moreover, churchgoers of the time listened to the passions in standard German, whereas we hear it in its original Ancient Greek text, adding extra distance between the work and the audience; and even our ears differ now, in terms of sound perception, of the sound volumes, frequencies and timbres we are accustomed to. So, when we say we remain faithful to the original, “faithful” denotes a disposition rather than indicates a result.

So, a historically informed performance is not a replication of the original performance, it is however closer to it compared to the transcription of 17th and 18th century music for a modern orchestra, something that used to be rather common.

That’s right; this was not however a matter of choice, but rather a matter of functionality. At a time when knowledge and ability to perform music in a historically accurate way was lacking, these astonishing pieces were performed by use of the means available. So there were many transcriptions, as for example Dimitri Mitropoulos’ arrangements of Bach’s organ works for a symphonic orchestra, which really aimed at communicating these creations to the audience of the time as well as they could, using the equipment they had access to.

The Coronation of Poppea at the Athens & Epidaurus Festival (Photo by Evi Fylaktaki, 2011)

The Coronation of Poppea at the Athens & Epidaurus Festival (Photo by Evi Fylaktaki, 2011)On April, a production of Henry Purcell’s The Fairy Queen will premiere at the Greek National Opera, under your music direction. Will you try to stick to the original in this case too?

Well, it’s not so much about the original work, more about the original sound and the original way. A work is debased not so much when we change notes but when we change its prosody. In this case we are, however, talking about the staging of a show, so the visual element is very prominent; the direction by Giannis Skourletis and bijoux de kant uses a very contemporary visual vocabulary. When The Fairy Queen was presented in London for the first time, it was an extravagant production, with a huge Baroque orchestra, many singers, choirs, special effects and scores of stage equipment. Ours is a very different approach; we have distanced ourselves from the original text – that is, Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, on which the work is based. We have designed a show that doesn’t have much to do with a 17th century extravaganza. We use a contemporary stage arrangement, in the relatively small Alternative Stage at the Greek National Opera. We try to remain as faithful as possible to the musical articulation, but we are of course far from recreating what Purcell had in mind.

So you use a different libretto?

There is no libretto per se. This is not an opera, but a masque; there is a basic prose structure, and music has a symbolic, if I may say so, connection to this prose, as musical parts have between them. So instead of moving in the direction of an opera-style staging, where the dramatic composition is much tighter, we chose the opposite direction: to make the English masque even more minimalist. Through the music, we created a new narrative thread.

So the liberties you take are not comparable to your work in L’ Orfeo – with a twist, your latest collaboration staged at the Athens Concert Hall, based on Monteverdi’s opera.

That was a different case all together. Inspired by Claudio Monteverdi’s own idea of using different instruments when the action takes place in the underworld, we took this concept one step further and, when Orfeo descends to the underworld, there was a shift in the dominant instruments, with the use of electric guitars, live electronics, like the Theremin, use of computers for electronic sounds and voice distortion etc. And yet, the music making was clearly of a Baroque nature. The sounds where different but the intention, the discourse, the way we used language and music were much more faithful to the original opera than most ensembles have managed to be in other productions of this work. In the Fairy Queen, the contrast does not lay in the musical composition itself, but in the pairing of this music with very contemporary visuals.

How did the Latinitas Nostra ensemble come into being?

How did the Latinitas Nostra ensemble come into being?

I had just returned to Greece from my studies abroad, and I wanted to form a circle of partners, with whom I could collaborate to fulfill my “artistic vision” (a term I now regard in a more ironic way). So I tried to locate these people in Greece who would not only speak the same language with me but also speak it in the same way, and who would be in the same place in life, meaning young, with studies abroad, contemporary studies in the same field, and yet were for some reason drawn back to Greece. That’s not to say we don’t have good collaborators who live abroad, we have some very important ones, such as Andreas Linos who plays the viol, but the nucleus is here. I wanted to create a platform of this sort, since there wasn’t already one there.

On the ensemble’s website, it is stated that “the point of departure -even indirectly- of the productions we present is Greece, the actual or the ideal one, the way it was ‘fabricated’ and used by 17th and 18th century Europe”. Was that aspect present since the founding of Latinitas Nostra?

Yes, it was there from the start. Of course, in Baroque, everything can be traced back to Ancient Greece, if one looks. As to how meaningful this connection is, that’s a different subject. You see, all late 16th – early 17th century theorists, who tried to identify the theoretical foundation of a new aesthetics, turned to Ancient Greece, of which they knew very little, and that via Arabic translations. So the question of whether Greece was just a starting point or an essential element of creation, during these roughly 150 years that cover the Baroque era is a question not easy to answer. After all, Ancient Greece constituted a different notion for a theorist in early 17th century Florence than it did for a musician with more than a dozen children, who worked at three schools simultaneously and had to compose a cantata on a weekly basis, like Bach.

Your ensemble has, however, presented productions where Baroque “conversed” with elements of Modern Greece, such as rebetiko music. Are you content with the outcome of such ventures?

Your ensemble has, however, presented productions where Baroque “conversed” with elements of Modern Greece, such as rebetiko music. Are you content with the outcome of such ventures?

Yes, very much so. All this had its roots in the Music Village, a project that takes place every summer in Pelion, which brings together musicians from very different backgrounds. There was an encounter there between the attendants of Evgenios Vouldaris’ yayli tanbur musical workshop and those of Nima Ben David’s viol workshop. These were two different realms that connected, listened to each other, played together and exchanged instruments, and I, although not present when all this took place, searched for a way to take part in this osmosis. It’s not just the sound, it’s about the different way each instrument perceives the notion of time, of a musical phrase and how much these two musical gestures can converge.

Our first production was “A voyage into the Levant” where, based on the journals of 17th century English travelers who journeyed from London to Constantinople, we had created a narrative on the encounter between the two worlds; sometimes they contrast one another, other times they converse, and there are times as if they say the exact same thing in a different tone. The other performance was “…for I will soon be laid in the earth…”, a meeting between Baroque and rebetiko; something we also tried in Salomé, presented at the Athens festival, under the stage direction of Nikos Karathanos. Although, in that case, I think -and I also wrote that in the programme at the time- Baroque music undermined the traditional Greek elements, the rebetiko “yeast” didn’t quite flourish in Stradella’s work. I don’t regard that as a failure, far from it; but in the other two productions we had managed to create a very genuine musical dialogue.

What are Latinitas Nostra’s plans for the future?

L’Orfeo, under the stage direction of Thanos Papakonstantinou, was a far greater success than we expected, and we would like to repeat it. For the time being, we are not seeking to mix western and oriental elements. Not that these were not very fruitful collaborations, or that working together with such wonderful musicians wasn’t a deeply rewarding experience; it’s just that our studies are in a different field, this fusion of genres is a wonderful adventure, but it is just one aspect of who we are and what we want to do. After all, we live in a country where one does not have that many opportunities to play Baroque music in its pure form. So when the question of musical experimentation came up, when discussing the production of the Fairy Queen, I was against it. If we want to remain innovative, we have to occasionally press a reset button and go back to the roots. What we have been looking for was a way to merge the sounds familiar to us as Greeks, the music we hear in social gatherings and celebrations, with the music we chose to study. These performances were cathartic for us, but this type of experimentation is not our only goal.

And your other plans apart from the ensemble?

The Fairy Queen’s final performance is on May 12, and on May 18 I conduct the Armonia Atenea orchestra along with an international cast of singers for a performance of Hasse’s Siroe at the Bayreuth Margravial Opera House. Other concerts with the Armonia Atenea are going to follow as well.

Finally, a more personal question: in an older interview you stated it was not your choice, as a child, to attend the conservatory. One might not imagine that.

Yes. I was interested in music but I really didn’t want to go to the conservatory – I think very few kids do. Although I began very young, I dropped in and out of it a few times. It was only in high school that I decided I wanted to take music seriously. At the time, I played the piano, and it was through a series of both fortunate and unfortunate events that baroque came into my life. The most fortunate of these was my encounter with my harpsichord teacher, Margherita Dalmati, at the Athenaeum conservatory. She was a special person, a pioneer of early music performance in Greece, and also a writer and translator. She was one of the main reasons I became interested in Baroque music.

Visit Markellos Chryssicos Youtube Channel

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Dimitris Kountouras on early music in Greece; Composer and harpsichordist Panos Iliopoulos on his (unorthodox) approach to music making; Rebetiko music: From the margins to the mainstream; Progressive metal band POEM in an exclusive interview just before their first European headliner tour

* Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi