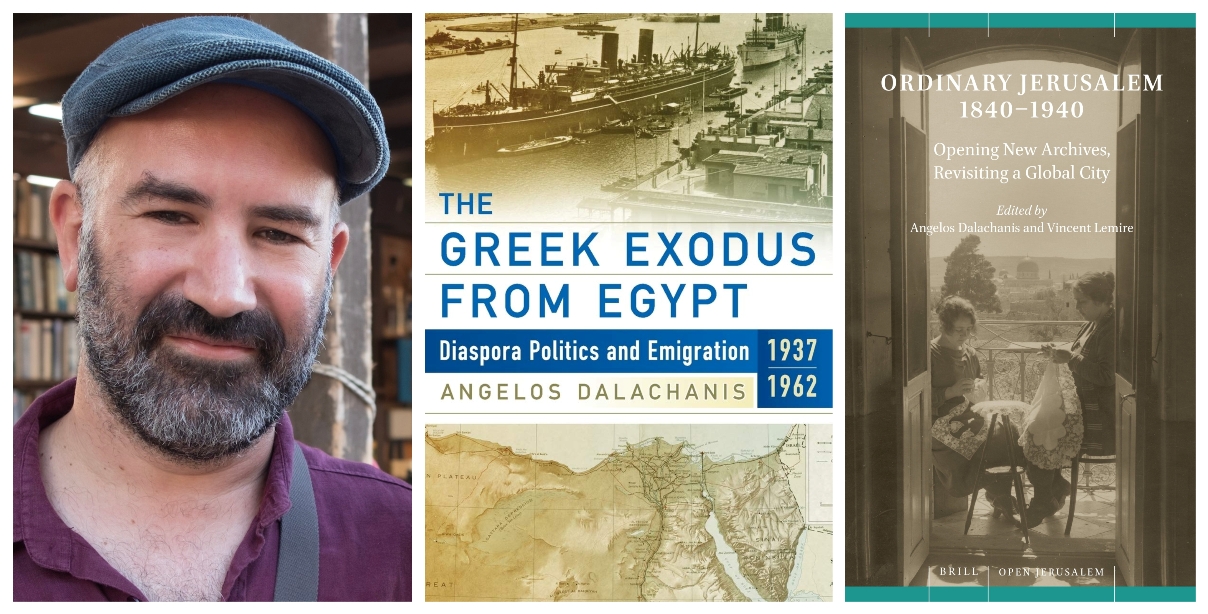

Angelos Dalachanis is a Researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and is based at the Institute of Early Modern and Modern History in Paris. He holds a Ph.D. in history from the European University Institute, Florence, and was a postdoctoral research fellow at the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies at Princeton University and at the French School at Athens. His research interests include the history of migration, labor and Greek diaspora in the Eastern Mediterranean in the modern period. He is the author of “The Greek Exodus from Egypt: Diaspora Politics and Emigration, 1937–1962” (2017) and co-editor with Vincent Lemire of “Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City” (2018).

Angelos Dalachanis spoke to Rethinking Greece* on the socio-economic characteristics of the Greek community in Egypt and in Jerusalem, the Greek ‘exodus’ of the early 1960s and how it relates to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the collapse of colonial empires, and the Cold War; the complex relations between the diasporic communities and the Greek state, and finally, the challenges the Greek diaspora communities face now in the wider area of the Middle East. As far a a more dynamic Greek presence in the Middle East is concerned, he emphasizes the role Greek Universities can play, by giving more grants to students from the area so that they can come and study in Greece, and utilizing the human capital of numerous students from Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, Iran and other Middle Eastern countries that have studied in Greek Universities over the last decades. He concludes that “to rethink the Greek presence in the Middle East, we need historical knowledge of the region and its people, as well as a strong imagination and an unbiased attitude”.

Greeks were the largest community of foreigners living in Egypt during the first half of the 20th century. How big was the Greek community in Egypt and what were its socio-economic characteristics?

Indeed, the Greek community was the largest foreign community in Egypt during the 19th century and until the mid-20th century, followed by the Italians. The Greek population fluctuated in the course of this period, reaching its peak in the late 1920s, after the arrival in Egypt of Greek refugees from Asia Minor. At that time, according to official statistics, there were approximately 77,000 Greek nationals living in Egypt, while the total population of Egypt was over 14 million. Just before the exodus of the early 1960s, the number of Greek citizens had already dropped to about 48,000, while the Egyptian population had almost doubled, approaching 26 million.

Other numbers that still surface from time to time in the public debate, and sometimes in the historical literature about the demographic power of the Greeks in Egypt, are based on arbitrary estimates, and always show the community to be much bigger than it appeared in the census. Many explanations can be given for the difference between official statistics and estimates. But there’s one explanation I would like to insist on. This difference is largely due to theuncertainty about who could be considered Greek in Egypt:Was it only those who were citizens of the Greek state?Those of Greek origin? The Orthodox Christians who spoke Greek? So, it is important to emphasize here that neither the census takers nor the Greek diplomatic authorities and communities had a clear picture of the exact number of the Greek population in Egypt, because it was not clear exactly who constituted this community. Even though we consider Greeks a single entity, the boundaries of the community were not firmly defined, but were fluid and constantly changing.

One thing is for sure. Even though Greeks never exceeded 0.6% of the overall population of Egypt in the early 20th century, their economic power however was immense, mostly because of the Greek economic elites’ dominant place in the cotton and banking sectors. This of course doesn’t mean that all Greeks of Egypt were rich; quite the opposite.

Most Greeks arrived in Egypt in the 19th and early 20th century as migrants. Initially, this movement concerned big merchants andtraders who were part of the Greek merchant diaspora around the Mediterraneanand Black Sea. In Egypt, they established nodes of extensivecommercial networks, encouraged by Muhammad Ali, the leader of Egyptfrom 1805 to 1848, who favored their settlement. Later, migration to Egypt also took the form of a mass movement of labor, as in the case of thousands of Dodecanese islanders who came to work on the construction of the Suez Canal. The newly arrived Greeks settled not only in Cairo and Alexandria, but also inhabited the old town of Suez and the newly founded cities across the Suez Canal area, Port Said and Ismailia, and penetrated theinterior, namely the cities of the Nile Delta such as Mansoura, Tanta, andZagazig, and also Upper Egypt.

Greek migrants who arrived in Egyptbecame engaged in a wide range of economic activities. The big Alexandrian cotton merchants and other entrepreneurs (Georgios Averoff, Emmanuel Benakis, Konstantinos Salvagos and others), who are now mostly known for their activities as benefactors, constituted only an extremely small part of the community. The economic elites greatly profited by the regime of the Capitulations and the British semi-colonial presence in Egypt after 1882. The Capitulations were bilateral agreements between the Ottoman Empire and individual states that regulated the rights and special privileges of foreigners within the empire, including Egypt. When in 1940 the Greek consulates conducted a survey on the professional activities of Greeks they revealed an interesting social stratification: the “clerks” constituted the majority of the workforce, which amounted to 33.5% of it. They were followed by the technicians (13.2 %), handicraft laborers (12.8 %), and the various shopkeepers (7.8%), while several other professions such as artists, waiters, teachers and professors, drivers, nurses, doctors, and all kind of liberal professions amounted to just over a quarter of the workforce. Finally, the upper middle class and the big bourgeois of the community—merchants and industrialists, various businessmen, landowners, and rentiers—accounted for 6.6%.We should not forget that the community also contained a significant number of destitute people with very low or no income at all. If the magnates mentioned above were involved in charitable activities (soup kitchens, orphanages, hospitals, etc), it was because there was a real need for them. In fact, there were people who relied on such practices for their survival.

In terms of context, there are similarities between Palestine and Egypt: both are Arab provinces under Ottoman rule, the majority of the population is Muslim, and they are under strong European influence, especially British, until the mid-20th century. Nevertheless, there are obvious differences between these two settings: Palestine did not have a significant port and Jerusalem was not a major merchant city, nor was it built around fertile grounds to attract rich merchants, or big landowners, as it happened with Egyptian cities. Even though itinerant workers from Egypt moved to Palestine for the construction of major development projects (such as the Palestine Railways) this did not result into permanent settlement. Moreover, Egypt had a high degree of autonomy from the Sublime Porte, and the Capitulations were extremely favourable to foreigners, more than in any other place of the Ottoman Empire.

The Greeks in Jerusalem tell us a somewhat different story from that of Greeks in Egypt. The Greek presence in Jerusalem has been invariably related to the existence of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, which is the oldest Christian institution in the Holy Land, the principal custodian of the Christian sacred shrines, and one of the most important non-state landowners in what is now Palestine and Israel. Greek and Palestinian Arab sub-communitiesformed the clergy and the congregation.Palestinian Arabs always formed the largest part of the Greek Orthodox congregation in Jerusalem, while Greeks constituted a small minority. However, due to historical factors, the Greek clergy always controlled the Brotherhood of the HolySepulchre, and thus the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate.

Beginning in the 1840s, European powers opened consulates in Jerusalem and the city attracted people who were for the most part religious, but also Greek migrants from the Ottoman Empire and Greece. In demographic terms the Greek population in Jerusalem reached its peak at the end of World War II with 1,500 people out of a population of about 165,000. Despite its small size, the symbolic capital of the Greek community was large, due to the spiritual and economic importance of the Patriarchate. Jerusalem’s Greek economic elites consisted mostly of liberal professionals and were not comparable with the strong economic elites in Egypt. There were, however, links and connections between Jerusalem and Alexandria, mainly through the religious networks between the Jerusalem and Alexandria patriarchates. Some of the most prominent figures of the Greek community in Egypt, who spoke Arabic and actively participated in the community’s intellectual life, had studied at the theological school of the Monastery of the Cross in Jerusalem. The best known example is Najib Michail Sa‘ati, a Greek Orthodox Arab born in Jerusalem in 1885, who translated and adapted the spelling of his name into Greek Eugenios-Michailidis when he moved to Alexandria in 1912 and became a prominent figure of Greek intellectual life in Egypt. Ηe is included in Despina Sevastopoulou’s 1950 book on “The Alexandria that is leaving” among other biographies of “Alexandrians of the last 50 years”, and his case is conceptualised in a recent article by professor Antony Gorman.

What were the main factors that made the Greeks of Egypt gradually leave the country? Conventional wisdom connects the ‘Greek exodus’ to the nationalization of many industries in 1961 and 1963 by the Nasser regime, but your research shows that there were other factors at play as well.

You are absolutely right in saying that Greeks left Egypt only gradually. People often leave one place to find a better future in another, and those Greeks who left Egypt did so because they were convinced that the country offered them no future or because they had better prospects elsewhere.

Greeks always left Egypt either after fulfilling the objectives that had driven them to emigrate there, or in times of economic crisis. In the post-war setting though, something fundamentally changed. Greeks stopped migrating to Egypt because it became more difficult to enter the country and opportunities for work and wealth dwindled.

The mass departure of Greeks did take place in the early 1960s, but the dismantling of the structural components that linked the Greek presence to Egypt had begun years ago. The most important structural change was the abolition of the capitulation privileges that foreigners had been enjoying in Egypt until 1937. The capitulations protected Greeks and other foreigners by exempting them from almost all taxes and guaranteeing freedom of movement and commerce. Moreover, they granted immunity from legal and judicial control. As long as the Capitulations were in effect, Egypt had no right to promulgate laws relating to foreign citizens, over whom Egyptian courts had no jurisdiction. The results of the abolition of the Capitulations in real life were not always immediately perceived.

The domination of foreigners as a result of the Capitulations and the British presence had not only economic and political but also cultural aspects. It led to a superiority complex toward the Egyptian population, apparent in the reluctance of the majority of Greeks to acquire fluency in Arabic. In other words, they refused to integrate into Egyptian society to any significant extent, as well as to “converse” with the Egyptian state, especially since after Arabic language had become one of the basic tools of Egyptian nationalism, and its use had been extended to all aspects of public life through the 1940s and the 1950s.

So, yes the nationalizations of the early 1960s did indeed take place and played a role, but they did not happen like a bolt from the blue. Measures associated with the process of transforming Egypt from an autonomous Ottoman province under European control into an independent nation-state, were taken also before the coup of 1952 and the ascent of Nasser to power, and contributed to Greeks’ decision to leave Egypt. Historians must expand the picture in terms of time and space in order to understand complex phenomena such as the Greeks’ definitive departure from Egypt. In doing so, it becomes clear that the departure of Greeks was not an isolated phenomenon, but part of broader population movements, relatedto three different historical developments: the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the collapse of colonial empires, and the Cold War.

You mention that many diasporic communities historically preceded the emergence of the Greek national state, which complicated relations between the new Greek state and “it’s” Diaspora. How have these relations evolved over the years?

The demographic power of the Greek nation and the geography of the Greek state have never been in complete agreement. Despite the fact that quite a number of Greeks live outside Greece since the foundation of the Greek state, the state has never developed a stable and consistent policy towards the Greek Diaspora. And despite the pompous statements of governmental and non-governmental actors who speak of an «ecumenical Hellenism», the Greek State does not treat all Greeks outside its borders in the same way. Its concern for the diaspora is determined by its own needs: the presence of Greeks in the territories of the Ottoman Empire, for example, supported the irredentist doctrine of the Great Idea and the need for geographical expansion. After 1922 and until the end of the Second World War, interest in the diaspora was limited. Diaspora interest was strengthened again by the need for reconstruction after WWII and was greatly renewed in the 1970s after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus and in the 1990s when the Macedonian issue came to the fore again.

The state turned its gaze in the most beneficial direction for itself, depending on circumstances: either to the East until 1922 or to the West in the post-war period.However, apart from the general geographical orientation, the institutional, political and economic aspects of relations between the state and the diaspora were mostly based on personal strategies and initiatives that rarely went beyond the period of one governmental or ministerial term, or one generation on the part of the expatriate community.

For Greece, it is itself at the centre, and the expatriate community revolves around it. But for many members of the Greek diaspora, this is not necessarily the case. Over time, numerous Greeks of the diaspora did not treat Greece as their sole or even major point of reference. For instance, there are cases of Ottoman Greeks who decided to migrate to the US, France and other Western countries without ever passing through Greece. Similarly, only approximately half of the Greeks who left Egypt moved to Greece. The rest moved to Diaspora settings all over the world, to Africa, Western Europe, Oceania and the Americas. For these people, the homeland was and is more of a cultural, imaginative space. But if we consider that “Hellenism has no borders”, as the Atlas Larousse illustré wrote back in 1901, for the additional reason that it is an imaginary space, we cannot disregard the fact of its multiple centers, both political (the Greek state) and religious or other symbolic (Istanbul, Jerusalem, Alexandria). So, the point of reference is not always and not solely Greece but areas in Asia Minor, Egypt, Palestine and other regions, mainly in the Eastern Mediterranean, where Greek populations lived for a long time.

What are the challenges the Greek diaspora communities face now in the wider area of the Middle East?

Each country of the Middle East has its own specificities. For instance, the Greek population of Egypt has three main components today: those who are descendants of the old flourishing communities and never abandoned Egypt; newly arrived expatriates who work for Greek or other western companies for a certain period of time; and clergymen and people close to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria.

Each of these sub-communities faces different challenges. I would say that the Greek secular presence, whose roots go back to the old Greek community of Egypt, is most at risk. Demographic decline and lack of proper education are the most important challenges. There are very few Greeks living in Egypt nowadays and the use of the Greek language is decreasing day by day. The Greek state, and especially the Ministry of Education, has a central role to play here. It should strengthen the educational structures in the area and listen more carefully to the demands of the communities. As for the demographic problem of Greeks in the broader area, we should probably reconsider who is a Greek in the Middle East and who can become Greek or come closer to the Greek communities.

Examples like that of Eugenios Michailidis, which I mentioned earlier, can show us how to envisage these relations in the future. You know, hundreds, maybe thousands of students from Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, Iran and other Middle Eastern countries have studied in Greek Universities over the last decades. Accordingly, thousands of immigrants who have lived and worked in Greece for many years have returned to their countries. Are there any significant efforts by the Greek state or other associations to maintain relations with these people after they return to their homeland? I strongly doubt it.

However, these people often have a solid knowledge of the Greek language and modern Greek reality. Some of them have been married to Greeks. The Greek state should establish ties with them and make them unofficial ambassadors of Greece, so that the country can play a more energetic cultural and economic role in the Eastern Mediterranean. More grants should be given to students from the area so that they can come and study in Greece. Greek universities have always been a hub for people from the region, but the Greek state traditionally has shown indifference to them. So, instead of providing golden visas and citizenship to people with controversial economic and moral status, because they pay a few thousand euros, we should find ways to exploit the human and cultural capital which is already there. These people should be creatively integrated into the actual communities and create the Greek communities of the future. To rethink the Greek presence in the Middle East, we need historical knowledge of the region and its people, as well as a strong imagination and an unbiased attitude. This will also help us rethink Greece and the ways in which migrant and refugee populations from the Middle East can be integrated into our country and become part of the Greek nation.

TAGS: DIASPORA | EDUCATION | GREECE-AFRICA RELATIONS | MIGRATION | MODERN GREEK HISTORY