The exhibition Democracy at the National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum (July 11, 2024 – February 2, 2025) marks the 50th anniversary of the restoration of democracy in Greece, and traces the relationship between art and political history in southern Europe.

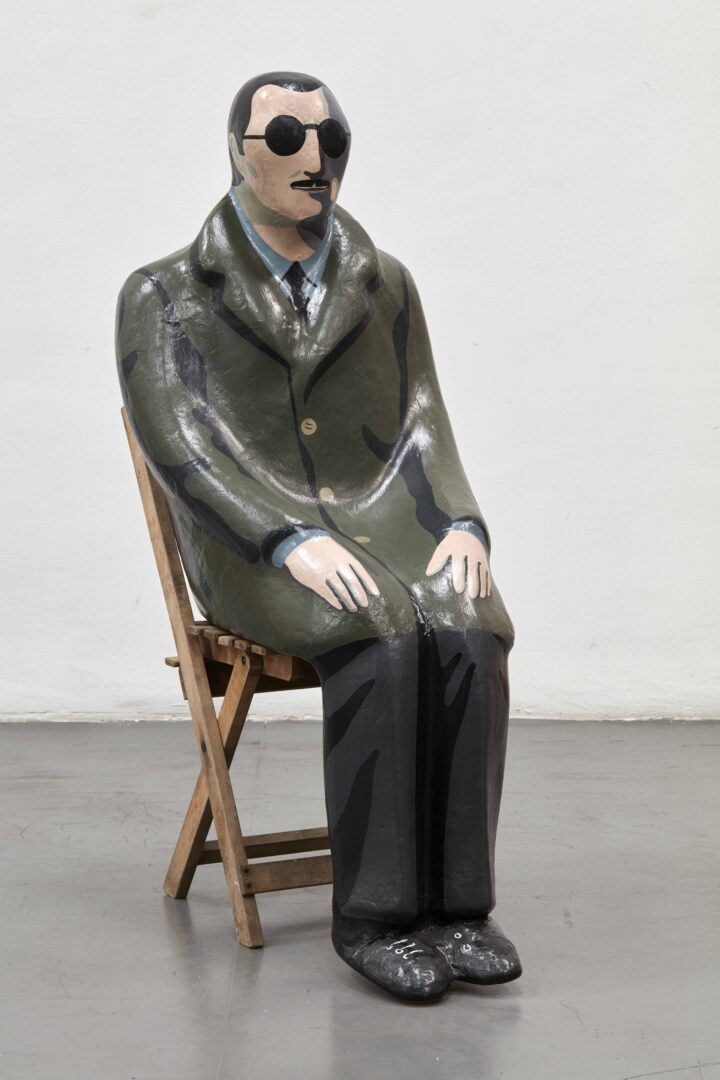

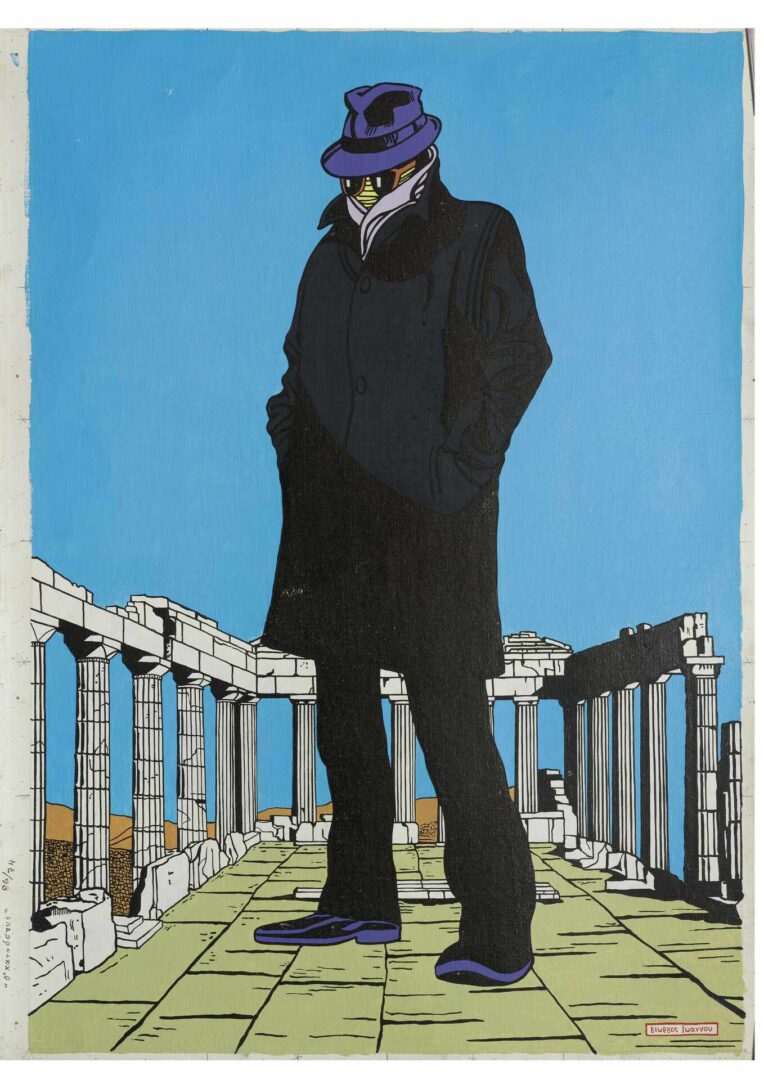

It is the first major event to explore the way struggles against authoritarian regimes in Greece (1967-1974), Spain (1936/1939 – 1975) and Portugal (1933 – 1974) found an expression in art. Featuring 140 works by 55 renowned Greek, Spanish and Portuguese artists, the exhibition focuses on the transition to democracy in these countries and the role of artists in calling for political freedoms.

Syrago Tsiara, Director of the National Gallery since 2022 and curator of the Democracy exhibition, spoke to our sister publication, GreeceHebdo*, about the political role of art and her vision as Director of the National Gallery.

Born in Larissa in 1968, Syrago Tsiara studied history and archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, and has worked at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki and the University of Thessaly, among others. She has also been director of the Center for Contemporary Art at the National Museum of Contemporary Art and of the Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art. Having organized over fifty art exhibitions in Greece and abroad, Tsiara is also involved in conferences and publications on issues such as the relationship between art and politics, memory, identity and the public sphere.

50 years after the restoration of democracy in Greece, the international exhibition Democracy at the National Gallery examines the political role of art in the face of authoritarian regimes in Greece, Spain and Portugal. What is the thread that links these three countries, and how does it emerge in the exhibition?

The year 2024 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the restoration of democracy in Greece, indeed half a century of uninterrupted parliamentary democracy following the overthrow of the military dictatorship (1967-1974). This historic step towards democracy in 1974 also marked the beginning of the period known as “Metapolitefsi”. That same year, with the Carnation Revolution, democracy was restored in Portugal after almost half a century of dictatorship by Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, while the transition to democracy also began in Spain the following year, after the death of the dictator Francisco Franco, who had maintained authoritarian rule since 1939.

There have been many tributes to the relationship between the arts and democracy in our country and elsewhere, yet the issue has never been addressed, in a comprehensive way, on the scale of a major exhibition for the countries of southern Europe. We lack the experience of coexistence to document the convergences and divergences of historical memory and visual representations in Greece, Spain and Portugal, to consider the links between revolutionary discourse and consciousness and the new art forms born in conditions limiting freedom and political demands.

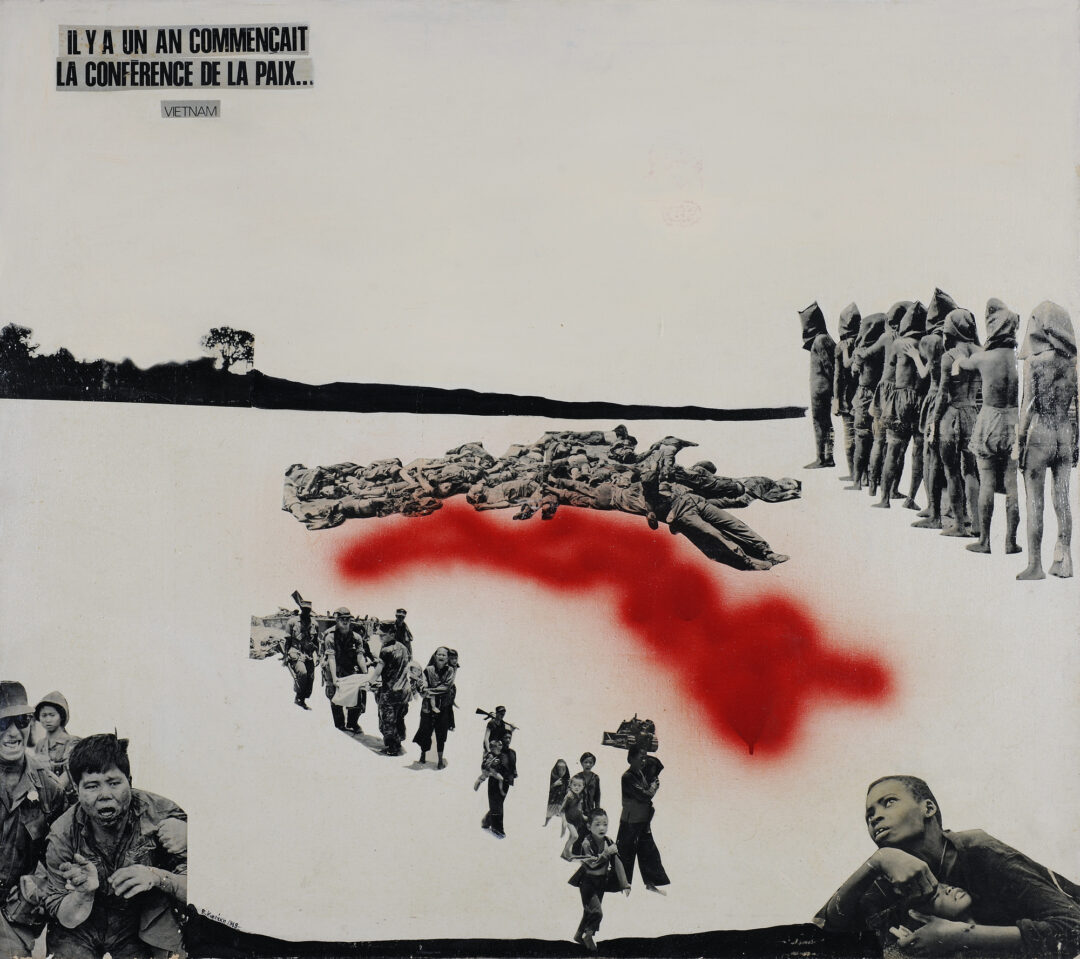

The National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum is at the forefront of this effort, organizing a major international exhibition on Democracy and Art in Greece, Spain and Portugal from June 2024 to early February 2025. The exhibition examines the meaning, content and visual expressions of the fight to overthrow authoritarian regimes in southern European countries, the affirmation of political freedoms and anti-colonial struggle. At a time of threatening resurgence of authoritarian forces in Europe, when achievements of democracy are once again under threat, an exhibition on how artists have been inspired by struggles against authoritarian regimes takes on added importance.

The exhibition focuses on the ’60s and ’70s in southern Europe. Beyond the political dimension, can we also speak of artistic exchanges, of currents common to the above-mentioned countries during this period?

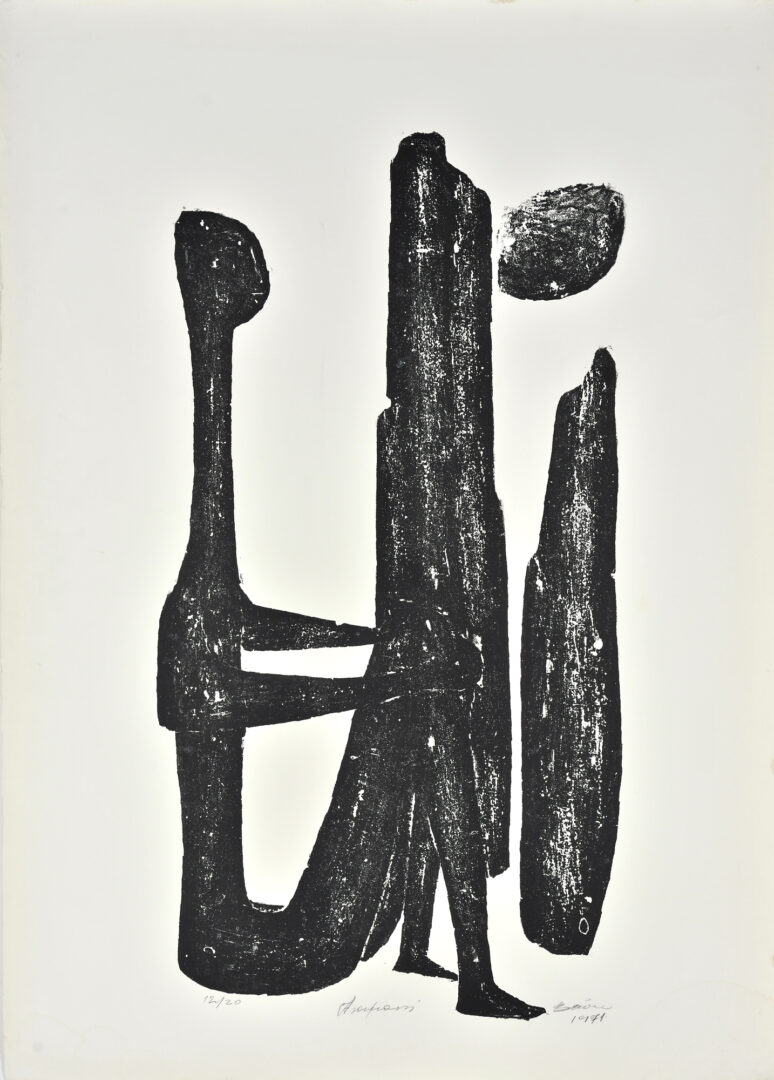

If we look for islands of familiarity in the methodology, the use of tools and the visual codes of representation of artists attempting to articulate a discourse against the stifling reality of dictatorships in Southern Europe, we should highlight the central points of convergence, notably collective action, institutional critique, the affirmation of visibility and the emphasis placed on body politics. In this context, we should trace resistant and emerging representational practices that emphasize the texture and gestural dimension of materials, the use of abstraction but also critical realism, the politics of visual arts and theatrical performance, the revival of the legacy of modernism, especially in the sense of installations, ready-mades, collage, video and pop art.

In Greece, the local representatives of New Realism, 1971-1973 (Chronis Botsoglou, Yiannis Psychopaidis, Kyriakos Katzourakis, Yiannis Valavanidis, Kleopatra Digka) through exhibitions in Athens and Thessalonica, debates and manifestos, actively declare their critique of the use of the image, a use mediated by mass culture, advertising and the media. The group seeks to reveal the deeper structures of visual culture and consciousness, as well as stereotypical representation and ideological manipulation.

In Spain, the Equipo Crónica group (1964-1981), formed by Rafael Solbes, Manuel Valdés and Juan Antonio Toledo, consistently and systematically embodies an affirmation of critical representation, as opposed to informal or abstract Spanish painting. This group sought to bring the public into direct contact with art through collective artistic actions, such as the Encuentros de Pamplona (Pamplona Meetings), one of the most massive artistic events of the summer of 1972. In 1977, Ernesto de Souza, the initiator of creative meetings in the spirit of Fluxus, organized a group exhibition and program of activities at Lisbon’s National Museum of Modern Art, entitled Alternativa Zero.

The exhibition highlighted the wealth of experimental trends in Portuguese contemporary art, including performance, improvisation and experimental theater practices. The aim was a tangible criticism of institutional models of art management and promotion, counter-proposing the alternative model of creative self-management, without distinction between older, well-established and younger artists. In this context, each participant was invited to act independently in the presentation of his or her work in the space and in the exhibition catalog.

In the case of Greece, what role did artists play in the restoration of democracy?

By creating posters for international anti-dictatorship groups, organizing mass demonstrations, publishing texts, staging concerts and performances, and taking part in exhibitions, artists brought international attention to the violation of human rights and the suppression of freedoms in Greece during the dictatorship. They also played a major role in raising awareness and rallying the public to denounce the authoritarian regime.

It’s often said that the country’s contemporary art has limited international visibility. Why is a visit to the National Gallery worthwhile, especially for a foreign visitor who probably came to Athens primarily to see the Acropolis?

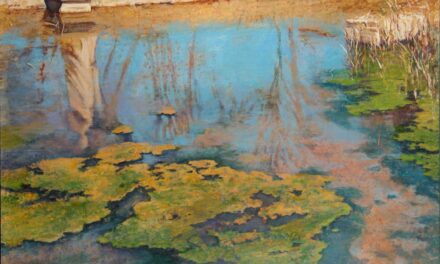

According to our first visitor survey, carried out this summer, 51% of the Gallery’s visitors during the summer months are foreigners, coming not only from European countries, but also from Asia and America. These visitors, who come from very different backgrounds, gain an overall picture of the evolution of modern Greek art and along with knowledge of the country’s visual culture. For example, genre scenes, landscape painting, orientalism and urban portraiture are central stages in the narrative path of 19th-century Greek art, a path in which we find some of the most important representatives of the Munich School, notably Nikephoros Lytras, Georgios Jakobides and Nikolaos Gyzis. In the work of these artists, we see richness and diversity in the depiction of scenes of everyday life, especially family and intergenerational relationships. Similarly, we also recognize the educational and idealistic dimension in genre scenes, as opposed to the emphasis on objective observation and documentation sought by realism.

In addition to admiring the diverse subjects and the creative dialogue with European movements, every visitor to the National Gallery can enjoy the mature works of painters who are at the center of our artistic iconography, a common ground with which we are all linked at the level of memory and experience, defining our identity.

The Gallery attracts all those who wish to admire the richness, quality and pluralism of trends in Greek modern and contemporary art, and for foreign visitors wishing to experience first-hand not only the renowned treasures of Antiquity, but also the modern art that reflects the country’s contemporary face, its distinctive character and its dynamic spirit. To this end, we continue to invest in the international promotion of the Gallery with focused initiatives and synergies.

What role do you think that the National Gallery should play, generally speaking? And what is your vision and future plans for the Gallery, the National Glypthotheque and the other annexes?

The National Gallery occupies a leading position in the country’s cultural life, while at the same time finding itself at a key moment in its history. Having resolved decades-long infrastructure problems, thanks to the cooperation and commitment of all those who worked to complete the new building and install the permanent collection, under the leadership of the late Marina Lambraki-Plaka, we are now at a new starting point; having already reached milestone goals, the Gallery has the infrastructure it needs to meet the challenges and demands of our times. Despite some shortcomings, it has an excellent staff as well as loyal partners, friends and supporters. It’s time for the Gallery to become more sensitive to environmental issues, more pluralistic, open and inclusive, to engage its collections and its history in a fruitful dialogue with the needs of society and the currents of contemporary thought.

The proposed policy aims to highlight the particular personality of each annex and enhance employees’ connection with the object of their work, aiming for a vibrant, multi-dimensional organism. Specific actions – exhibitions and educational programs – are planned to this end.

In general, the future of museums – their resilience, their socio-cultural importance and their relationship with the public at a time of repeated crises – depends largely on their adaptability and the development of new operational models, in both analog and digital environments. We should always be addressing multiple audiences, from the immediate environment, the neighborhood, the city, the country to the international public with whom we can now communicate with the means of digital technology that offer unlimited possibilities.

Clearly, synergies are essential for the sustainability and resilience of all, so cooperation with other cultural and educational organizations in Greece and abroad must be strengthened, not only in terms of the artistic program, but also in terms of joint research and use of resources, as well as the exchange of experience and know-how.

Today, the interpretation of cultural heritage , community relations in analog and digital environments, the promotion of critical thinking combined with the sharing of knowledge, expand the role of the National Gallery.

In short, the Gallery has the prerequisites and the vision to increase its influence through international artistic initiatives and synergies concerning social, institutional and cultural issues, but also by contributing to the improvement of the quality of everyday life. The Democracy exhibition, with its public program and parallel actions, is a clear example of this new vision.

*Interview by Magdalini Varoucha (Intro image: Alexis Akrithakis, La Grèce originale, 1967)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Discover the National Gallery of Athens; ‘A National Gallery for Everyone’ | The new programme for 2023-2024

TAGS: ARTS