The Municipal Art Gallery of Athens is one of the most important museums of modern and contemporary Greek art, featuring more than 3.000 works in its permanent collection. It was founded in 1914 and has changed venues several times. It is now housed in a two-building compound on Avdi Square, in the inner city area of Metaxourgeio. Apart from the permanent exhibition, various temporary exhibitions and events are hosted in both its main compound as well as the Eleftheria Park Arts Centre.

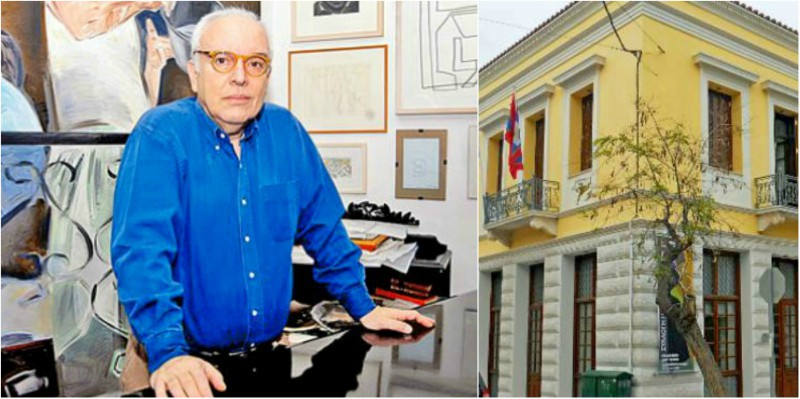

In 2015, Denys Zacharopoulos was appointed artistic adviser to the Municipality of Athens responsible for its cultural policy, including the Municipal Gallery’s direction. Zacharopoulos is a renowned art historian, critic and writer, who has collaborated as a curator with a number of prestigious institutions internationally. He has served as member of the curatorial team of the Documenta 14 in Kassel, commissioner of the pavilion of France at the 1999 Venice Biennale, consultant for the National Foundation for Contemporary Art in France and Inspector General of the Delegation of Plastic Arts at the French Ministry of Culture, to name a few of his career highlights. Following his return to Greece in 2000, he taught History of Art at the University of the Aegean and, from 2006 to 2015, was the director of the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki.

We met with Denys Zacharopoulos at the premises of the Gallery, where we talked about the role of the state in protecting and promoting culture, the mission of public museums, the political nature of art and the difference it can make in the lives of each of us. He also presented to us the Municipality’s 2018 exhibition programme. It begins at the end of January with an exhibition regarding the Gallery’s collection under the directorship of prominent artist Spyros Papaloukas (1892-1957). The themes of this year’s exhibitions have been strongly influenced by the designation of Athens as World Book Capital (April 2018-April 2019). These include “The stories of Alexis Akrithakis”, with drawings, notes and illustrations by the acclaimed painter, programmed for may, “The book as a work of art”, set to open in October, and “Greek artists and books 1914-1964”, scheduled for September, with illustrations of famous books by renowned artists.

The 2018 programme begins with an exhibition about the artist Spyros Papaloukas. Would you like tell us a few things about it?

The 2018 programme begins with an exhibition about the artist Spyros Papaloukas. Would you like tell us a few things about it?

This is an exhibition on Papaloukas not as a painter, but as artistic consultant and then director of the Athens Municipal Gallery, from 1940, when he was appointed, until his death in 1957. We have all the archives for every transaction, every artwork bought by the Gallery in that period, all the documents and letters showing which purchases he personally endorsed and actively promoted, and which were imposed either by the mayor, by circumstances or even by the Germans during the Nazi occupation. They illustrate the various difficulties encountered by someone in his position, the efforts to reconcile different goals and interests, and making the best choices with limited options. It has to do with the history of museums, and the way historical events affect their collections.

In the art of the 20th century’s first decades we encounter the notion of Greekness – the sense of true Greek identity. Isn’t that true for Papaloukas’ works as well?

Papaloukas did not embark on a quest for the true meaning of Greekness, as did the artists that followed. He came from a village and started out as a child helping with religious paintings in churches. He later got a scholarship and studied art in Greece and then abroad. For him, as well as for Konstantinos Parthenis and other artists of the 20’s generation, Greekness is not an abstract notion –as it is, in my opinion, for the 30’s generation– but instead, it has to do with journeying across Greece, as he had done, travelling and painting in every possible place. It is not a search for identity but simply about appreciating the natural features of this land, with an emphasis on the light, a very important aspect of painting. The differences in the landscapes and natural light make Papaloukas works change, according to the scenery of the region of Greece where he paints each time.

What about contemporary Greek artists? Can they compete with this recent past?

It is a question of context. You see, at school I was considered to be tall, but compared to kids today, I would appear to be rather short. So, height is a relative measure, and it is viewed differently in every period of time. Likewise, people, and particularly artists, need to see the world with new eyes every time and redefine it. In Greece I believe we are very lucky: having lived through a series of crises, a large number of intellectuals do not lose hope, and there are also many young truly talented people, even if many of them choose to work abroad on account of the difficulties faced in our country today.

You have stated before that institutions, both public and private, can once again become an integral part of cultural life, especially in times like these.

You have stated before that institutions, both public and private, can once again become an integral part of cultural life, especially in times like these.

Within today’s globalised market, solutions can only be found in cooperation. The state must work together with regional authorities –municipalities, communities etc – and with members of the private sector. It is of capital importance for a state to protect and promote culture. In my generation, that was the foremost purpose in wanting to become part of the European Community: to know that culture, civilisation and the public interest – as in free education – would be secured against brutality.

So you are particularly interested in safeguarding the public character of the Gallery.

I am proud to say that all municipal cultural facilities offer free admission. Last year, for the Maria Lassnig exhibition, we collaborated with Hans-Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London, which don’t charge admission either. At the press conference, he shared a story about the driver of a cab he rode, who spoke very fondly of the Serpentine. Not an art fan himself, he had taken his four-year old daughter there to use the restroom while out on a stroll in the park with her many years ago. He chose the venue simply on account of the free entry. Afterwards, the little girl would not leave, fascinated by the artwork around her. She is now completing her post-graduate studies in architecture, and her father credits her success to the Serpentine Galleries.

My generation had this mentality of going places, roaming in Athens, but young kids now don’t do that often. So how could you attract them, unless you make it at least easier for them? Growing up, what really helped me was the exposure to a multitude of stimuli – buildings, paintings, conversations, music, films. I didn’t always understand much of what I heard or watched, and yet they shaped my life. It’s about learning not to fear what you don’t understand.

You have invested in the educational aspect of the Municipal Gallery.

We have a continuous series of educational programmes, such as guided tours given by many different people, including the gallery curator and myself. On the occasion of the Alexis Akrithakis exhibition, for instance, we have scheduled weekly open discussions, each time with two of the painter’s acquaintances, ranging from his physician, his gallerist and his daughter to his colleagues and collaborators, on the subject of his art and the meaning the exhibits we will be showcasing.

Does this educational purpose dictate some of the choices in the gallery’s schedule?

Does this educational purpose dictate some of the choices in the gallery’s schedule?

First of all, I believe that a cultural space is by principle linked with the audience and aims to offer each and every visitor a new perception. The audience is extremely diverse, of many different age groups, as well as cultural and educational background, and you have to address every one of them, not just the connoisseurs. I am not however looking for “the average visitor”, arbitrarily setting the bar at a certain level. With each exhibition, we have to try and draw the people in, and this doesn’t refer to the guiding and information provided, but to also designing an exhibition effectively.

In an exhibition I had curated many years ago in France, we had organised a series of music performances using the exhibits as a backdrop, and the concertgoers ended up contemplating the artwork. You don’t necessarily have to supply abundant information, for fear of the audience missing or not understanding something. People also have to learn to just look without any instructions, to gaze, even to linger and idle.

As you mentioned above, many young intellectuals today choose to leave the country. You have had an illustrious career abroad, mainly in France, and yet decided to return to Greece.

This was basically a coincidence. In a way, you never “lose” your homeland. As I recall, Carlo Ginzburg –a noted Italian historian visiting Athens a few years back– was asked a question in the course of an open conversation at the Italian School, on his perception of ethnic identity: he was born in Italy by a father of Russian Jewish descent, and later lived in the USA for many years. He answered that, at some point, he understood that (barring racist remarks) he didn’t mind criticism against any country or nation that was close to him, except Italy. He felt he could criticise Italy, but turned defensive when someone else did this. It’s like a parent: you will reprimand your children, but won’t tolerate a stranger scolding or badmouthing them.

This is how I have always felt about Greece, even after receiving the French citizenship. When I resigned from my position at the French Ministry of Culture in 2000, it was partly due to the political climate at the time –I could see that the far right was on the rise and, indeed, less than two years later, Le Pen would face Chirac in the runoff election– and partly due to family matters, following the death of my father. Of course, at the time, things were looking up for Greece, on many levels, but turned out differently later. I have however never regretted my decision, as I have never felt French the way I feel Greek; deeply rooted and integrated in Greek society, feeling naturally at home here.

So the reasons for this change were partially political. In an older interview, you have stated that art is political de facto, because it is a form of public discourse.

So the reasons for this change were partially political. In an older interview, you have stated that art is political de facto, because it is a form of public discourse.

I deeply believe that. It’s like marriage; there might be a metaphysical aspect to it –or not– but what is undeniable is its significance as a political act. Mind you, when I say “political”, I don’t mean politicised art. For the first decades after its creation, a work of art is subject to copyright but then, once it enters public domain, once it becomes part of cultural heritage, it is protected against destruction. It is a public good, meant for public exposure.

My favorite museum is still the “gallery” of my childhood: roaming through the streets, I would often come across an artwork, seen through an open window. In those times, if the owner saw me staring at the work of art, they would sometimes invite me in to take a closer look, and offer information regarding the work and the artist. That is the mission that a museum should serve, to function as an open window between the private and the public life of people.

This for me is the Municipal Gallery’s foundation stone. This is why I place such importance on free admission, as I said before. Art can free you, it can bring out your innermost feelings, bring you great discomfort or great comfort. It is a political given, and the most potent remedy against baseness and vulgarity, it is the best drug substitute, able to give you the most striking hallucinations. Art could have been our society’s most powerful elixir, if only we had acknowledged its importance and potential, instead of treating it as a frill. It is a window to the world, and it is the state’s responsibility to open it for the public. As you can see, people in our country become increasingly introverted, out of fear. I wish more of them would have the opportunity to open up through art.

Athens Municipal Gallery on Facebook

See also on Greek News Agenda:

Athens as a cultural spot: Nikos Souliotis on Athens’ modern cultural identity; Marina Abramović: Athens grows as a major cultural spot; Ares Kalandides on rebuilding the country’s reputation; Katerina Koskina on the need for cultural dialogue & EMST’s role as an arts capsule for the city branding of Athens; Elpida Rikou on the Learning from documenta project

Arts in Greece: Alexandros Psychoulis on the idea of symbiotic bliss & the reality of working as a visual artist in Greece; Gary Carrion-Murayari on “The Equilibrists” & the contemporary arts scene in Greece; Efi Kyprianidou on Art and Compassion; Athens School of Fine Arts celebrates 180 years

* Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi