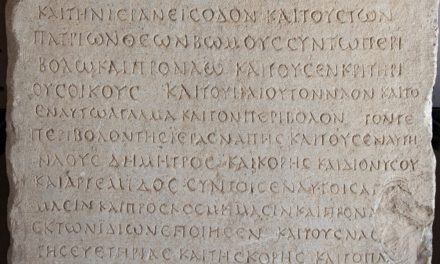

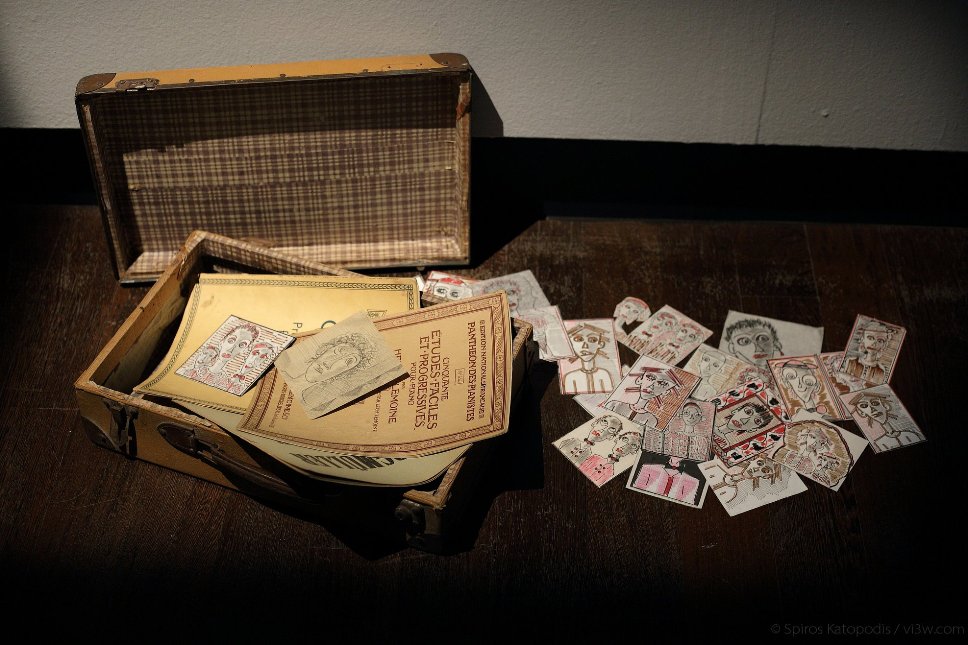

“Cruise: A floating Archive” Exposition. Photo: George Georgakopoulos (Cheap Art official page)

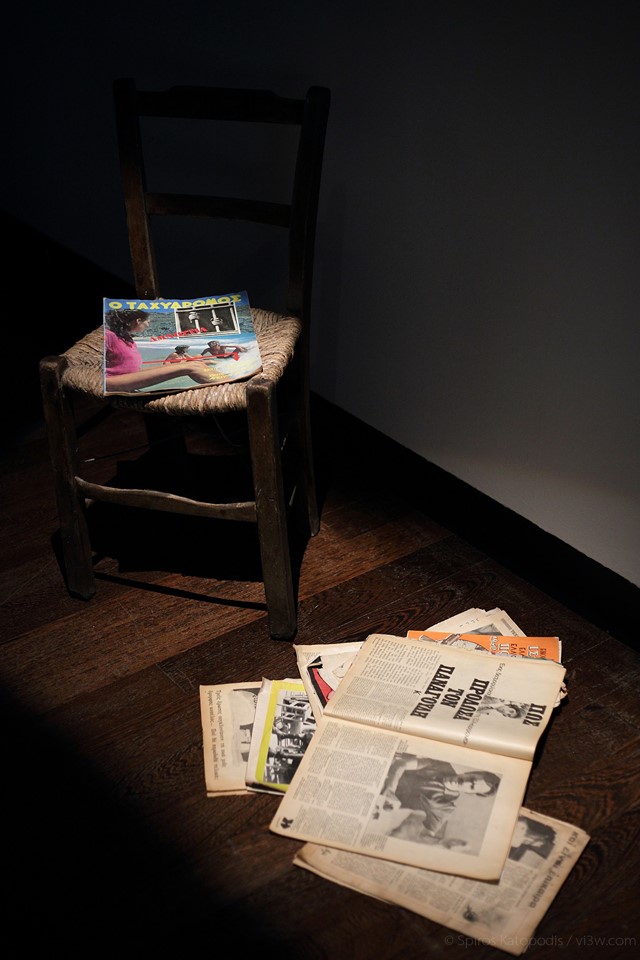

How could a humble bus ticket from the sixties promote historical research? Is history a closed, too reverent to touch, system? How is history produced and what is the role of the historical sources? Historistai (Hιστορισταί), a group created 4 years ago in order to organize events about public history and familiarize the public with archives and the study and production of history, deals with similar questions. In “Cruise, A floating archive”, an exposition recently organized by Historistai, they used Vassilis Kofinas’ private archive to study how a personal experience could be incorporated into a wider historical context and see what questions about contemporary reality emerge.

The group also organized a round-table discussion about Greek archives and their potential in historic research that took place in the context of the exposition on September 25, under the title “Document, exhibit, archive”. Irini Gratsia, archaeologist and coordinator of Monumenta cultural organization, George Thanos, head of “ASTY” cultural group, George Polydorakis, Head of the Hellenic Republic Ministry of Foreign Affairs Service of Diplomatic and Historical Archives, Sotiris Rizas, Director of the Modern Greek History Research Centre of the Academy of Athens and ΕΛΙΑΜΙΕΤ(Greek Literary and Historic Archive of the National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation) historian andmuseologist Alexandra Haritatou, participated in the discussion co-ordinated by historian, founding member of Historistai group, Maria Sambatakaki.

Panel (from left to right): Sotiris Rizas, Alexandra Haritatou, Maria Sambatakaki, George Thanos and Irini Gratsia (Hellenic American Union)

Irini Gratsia, coordinator of Monumenta cultural organization, noted that the organization seeks to protect architectural heritage in Greece and Cyprus and this refers to monuments of all historical periods. Founded in 2006, it launched in 2013 a cataloguing program for all Athenian buildings dating from 1830 to 1940. As would be expected, researchers came across many archives as they interviewed building owners who used documents to record their history. Researchers scanned archive contents anddocumentedmore than 10,600 Athenian buildings, as well as conducted some 200 interviews. The program is in progress and is currently at documentation stage. The Monumenta group has ended up with an important archive it wants to preserve.

When the documentation program began, the only database available was that of the 2.500 -3.000 Athenian listed buildings. The 10,600 buildings dating from 1830 to 1940 catalogued by Monumenta shows there is a big number of buildings that deserve preservation. The researchers started walking around Athens to document buildings from scratch, given the absence of previous records. So far, 9000 buildings have been registered in a data base, but it can’t be said that they have been fully documented. It’s not, for example, certain when exactly they were constructed and by whom. To this end, verbal witnesses are of great help, as well as public documents. It should be noted that the Athens Urban Planning Office Archive for buildings dating before 1930 has been destroyed and this makes things more difficult, whilst the respective Thessaloniki Archives have been digitized. Athens is a living archive, Athenians love and live their city’s history but there is a strong need for respect and protection of public space, Gratsia concluded.

“Cruise: A floating Archive” Exposition. (Hellenic American Union)

The goal of the Asti team, noted its head, George Thanos, is to organize historic walks in Athens. So far, it has organized nine historic walks and has cooperated with artists and historians, although no one in the group is a historian. The group began operating at the peak of the crisis in 2012, a period of deep frustration. The historic walks aimed at changing the frustration narrative by changing the images and experiences of the city through history. The walks focused on neighborhoods’ mini-history, as well as on how Athens is reflected in contemporary or older literary texts (such as the work of Zacharias Papantoniou, Kostas Tachtsis or Giorgos Ioannou) and in this context, some of the walks focus on city cafes and cemeteries.

We are lucky to live in Athens which is a palimpsest, with many layers of history, noted George Thanos. “When we started organizing the history walks, we wanted to visit the lesser known and run down neighborhoods of Athens, such as Dourgouti (neos Kosmos), Omonoia and Gerani (a neighbourhood close to Omonoia) and try to change their narrative. We wanted to bring other aspects of these neighbourhoods to light. The first historic walk (co-organised with Documenta) took place in Dourgouti. This neighborhood was where the refugees from Smyrna settled in 1922 and we revisited the period. The historic walks managed to change the perception of certain areas of the city for those who participated. The fact that Athens has many layers of history cuts both ways. We live in the same places with our ancestors, and while there may be protected areas, such as the Acropolis and Thision, there are also monuments like that of Lysicratis immersed in the city and you can enjoy your coffee near them. History can offer a reason to love the city we live in”, George Thanos stressed.

“Cruise: A floating Archive” Exposition. (Hellenic American Union)

George Polydorakis, in his presentation of the work of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Service of Diplomatic and Historical Archives, underlined that it keeps all Greek diplomatic correspondence since the founding of the Greek State to the present, with the exception of the last five years. The collection aims to organize and index the material, make it accessible to academic research or for reference by the various departments of the Ministry. The importance of the archive has been gradually realized by all Governments as historic memory is an important part in drawing foreign policy. The Service of Diplomatic and Historic Archives also organizes events that aim at promoting its collections and participates in networks of peer Diplomatic Archives.

The making of a public archive was not difficult, said Polydorakis. We were familiar with the material, i.e., documents of the various departments of the Ministry as well as from the Greek Embassies around the world, in theory. Things however were difficult in practice, because there was no archival policy in Greece for many years and it’s still nonexistent in many cases. The MFA Archives were founded 80 years after the establishment of the Greek State and during the first years it was used as a depository for old and useless documents. The effects of this lack of interest are evident today in the massive amount of archival material which has not been catalogued yet. The importance of the Archives became clear during the Imia crisis in 1996, when they offered valuable historical evidence, and they are frequently used ever since. Another problem is the lack of space. There is also the challenge posed by the digital age and the question is how to make digital communication (emails etc) historical material, how to make it accessible to future historians.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has digitized all the material dating from the Greek Revolution to 1924, which is accessible on the internet, and it will continue digitizing its collection. Over the last twenty years it has launched the repatriation of documents from Greek diplomatic missions abroad. The Archives operate on the basis of an open archive rationale: a committee decides on the applications submitted by researchers for access to hard copy Archive material, about 95% of applications are accepted, with the 5% relating to classified or unsorted material.

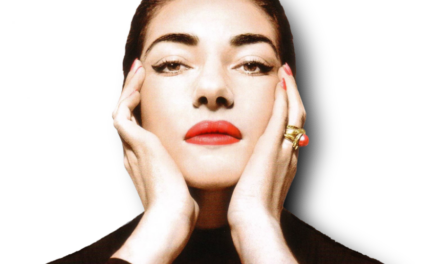

One of the oldest archives in Greece, the Greek Literary and Historic Archive (ELIA), was represented by Historian Alexandra Haritatou, who is the daughter of the Archive’s founder Manos Haritatos. It started as a hobby for Haritatos and Dimitris Portolos, who collected first editions of literary works, among other things. The collection grew and expanded to other types of documents such as newspapers and archives. Many individuals donated their archives. By 1980, the National Literary and Historic Archive had amassed 1300 archives of important individuals from the country’s political and cultural life. This includes the Kolokotronis Family Archive, Tsirkas, Palamas, Eleftherios Venizelos as well the Alexandria Patriarchate etc. The collection includes 200,000 photographs (of portraits, cultural and sporting events, wars etc). The library counts more than 100,000 volumes and the map collection comprises over 2000 maps. Over 100.000 documents have been digitized and are accessible. ELIA became part of the National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation in 2009 and it is open to all researchers regardless of their status and age.

One of the oldest archives in Greece, the Greek Literary and Historic Archive (ELIA), was represented by Historian Alexandra Haritatou, who is the daughter of the Archive’s founder Manos Haritatos. It started as a hobby for Haritatos and Dimitris Portolos, who collected first editions of literary works, among other things. The collection grew and expanded to other types of documents such as newspapers and archives. Many individuals donated their archives. By 1980, the National Literary and Historic Archive had amassed 1300 archives of important individuals from the country’s political and cultural life. This includes the Kolokotronis Family Archive, Tsirkas, Palamas, Eleftherios Venizelos as well the Alexandria Patriarchate etc. The collection includes 200,000 photographs (of portraits, cultural and sporting events, wars etc). The library counts more than 100,000 volumes and the map collection comprises over 2000 maps. Over 100.000 documents have been digitized and are accessible. ELIA became part of the National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation in 2009 and it is open to all researchers regardless of their status and age.

Manos Haritatos was one of the first to discover the value of ephemeral documents and objects, that is, things that have been destined for ephemeral use, such as labels, cards, theatre programs, advertisements etc. Although such documents are massively produced, they were usually doomed to oblivion as they were not considered to be of historical value. Small items such as tickets, coupons etc that were used as bookmarks tell us a lot of things about that period’s aesthetics and needs and it’s important that they be preserved. These ephemeral objects could tell a lot about everyday life. The Greek Literary and Historic Archive owns a collection of more than 10.000 ephemeral items.

“Cruise: A floating Archive” Exposition. (Hellenic American Union)

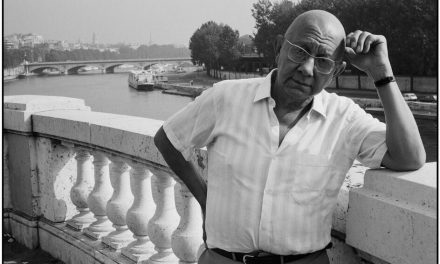

As Sotiris Rizas, Director of the Modern Greek History Research Centre of the Academy of Athens, underlined, the Centrewas founded in 1945 and its initial name, Historical Archive of Modern Hellenism, shows its close connection with archive research. The establishment of the Historical Archive took place at a period when other important archives also existed in Greece (such as the General State Archives which were established in 1941) and its main mission was to collect and preserve archival material. The archives were always accessible to researchers. Today its mission has a wider scope. Due to the economic crisis, the Modern Greek History Research Centre does not purchase archival collections anymore, but there are is already a very important collection in place that enables historical research, while it also publishes a journal and other publications. The Modern Greek History Research Centre has a complementary function to other important archives, such as the General State Archives and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Service of Diplomatic and Historical Archives which have evolved greatly during the last twenty years.

There is no objective approach to historic sources, Rizas notes, as our personal views affect the process. We have the obligation not to study the sources with prefabricated beliefs. We need an open mind. We often observe the use of history as a tool for political purposes and this is not the best way for society to find answers. Traditional archives must survive to help historical research. History is not a closed system and this is something that younger generations have to understand, hopefully through education, Rizas concluded.

F.K.